Feb 19, 2024 Politics

One of Jacinda Ardern’s distinguishing features was, astonishingly, her shyness. Before every question time, when she was prime minister, her stomach was in knots. What would the Opposition ask? And would she blow it? Even at the height of her powers, effortlessly communicating complexity, fear and reassurance in Covid-19 press conferences, Ardern would spend the hours leading up to 1pm agonising over what she knew, what she didn’t know, and what journalists might ask. Would she blow it? Over time, she had to perfect the art of projecting confidence, if not necessarily feeling it.

Our new prime minister, Christopher Luxon, by contrast, is confidence, bottled and labelled in a navy blazer. The former Air New Zealand chief executive arrived in office sure of his abilities, his policy programme, and his new partners in the form of David Seymour and Winston Peters.

And yet he arrived as a surprisingly weak personality.

When Luxon took to the stage at the Diwali festivities in central Auckland the day after learning his party had lost two seats on the special votes, he made a point of publicly addressing one person before any other: Winston Peters. “It’s good to see you here too, sir.” The emphasis fell on “sir” more slavishly than respectfully. Was he really sucking up to the old general in public?

Luxon had spent the day after the election talking up his negotiating experience. He had, apparently, closed many a merger and acquisition. As the talks dragged on — eventually reaching 40 days — the hitherto-patient press pack inquired: what deals have you closed, Mr Luxon? The incoming prime minister refused to specify any mergers and acquisitions he was a part of, but at that point his negotiating strategy was obvious enough. Step one, sweet talk Winston Peters. Step two, refer to step one.

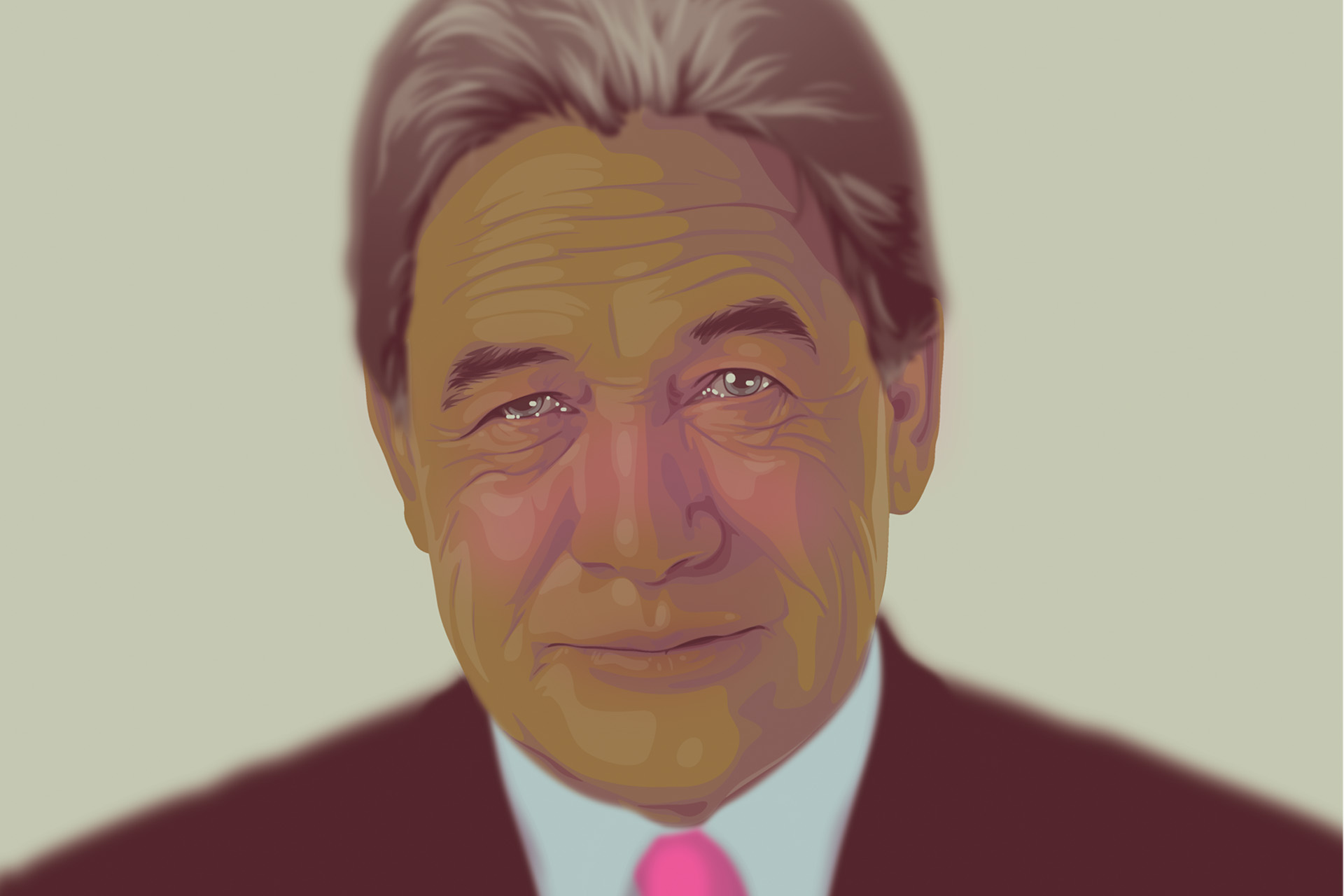

But Peters isn’t so easily flattered. The tributes to the old general’s exalted person are secondary to his primary objective — restoring a nationalist state. Peters is Parliament’s last Muldoonist. Unlike his deputy, Shane Jones, who was a Māori radical in the 1980s, a neoliberal in the 1990s and 2000s, and a conservative in the 2010s and 2020s, Peters has never had a crisis of faith. He spent his early years in Parliament cultivating a reputation as Muldoon’s successor as leader of the National Party, but, ever since he engineered his exit from the party in the early 1990s, he has (in his peculiar way) been auditioning for that same successorship. When the new triumvirate took to the stage in the Beehive banquet hall — Luxon facing the audience in the centre, Peters to the left, and Seymour to the right — the old general did exactly as Muldoon would’ve done: he had a go at the media. “Mathematical morons”, etc…

Luxon had to intervene — “all right, all right” — cutting a surprisingly weak figure. Seymour had spoken earlier to his party’s policy achievements, cutting an equally surprisingly statesmanlike figure, while Winston was, well, Winston, controlling the stage at will. Luxon is never flat — as a politician he’s always ‘on’ — but he lacks the charisma to hold a room. Presumably, that includes the negotiating room, too. If the new coalition agreement is remarkable for anything, it’s what National was willing to concede to Peters: the foreign buyers’ ban remains, cutting at the heart of National’s tax plans, and the provincial growth fund is back, though renamed the regional infrastructure fund, at a cost of over $1 billion. The latter concession is especially remarkable after Nicola Willis spent the campaign crying wolf at Grant Robertson’s fiscal management. Nothing was left in the cupboard, Willis said, presumably forgetting to mention nothing was left except for whatever was necessary to secure Peters’ votes in Parliament.

The asymmetry in the coalition partly reflects Luxon’s weakness as a politician. But, equally, National enters the 54th Parliament as a weak party winner — Luxon’s party won a significantly weaker party vote than Bill English in 2017, he has significantly weaker preferred prime minister ratings, and he’s wound up with two support parties refusing to lie down and take it. Even Seymour, whom commentators were picking as the more pliant party leader, refused to compromise on core policy. Seymour, like Peters, understands that an agenda demands implementation, hence Act’s control of the regulatory and workplace relations portfolios in the coalition agreement. Luxon, who approaches politics more like brand management, appeared to struggle initially when he discovered Peters and Seymour had a list of things they wanted to achieve. As the former CEO of an effective government monopoly (the government owns half of Air New Zealand and the company can ruthlessly exclude competitors, leveraging its strong balance sheet), Luxon has probably never had to compromise like this before.

This is the difference between an executive and a prime minister. Executives can drive their agenda with, for all intents and purposes, full control over tactics, expenditure, hiring and firing, and more. Prime ministers must drive their agenda through persuasion, compromise and the exercise of the soft authority of the office. Technically, Parliament controls the budget, not the prime minister. Public service chief executives control hiring and firing, and tactics too. Where those CEOs are obstructive, the prime minister’s best recourse is to the public service commissioner, who may or may not take action. And Cabinet collectively controls strategy. Strong prime ministers can heavy their Cabinets (think Helen Clark) but Luxon is hardly likely to be a strong prime minister. Is he really going to come down hard on Peters? Or even Seymour?

In some respects, a CEO position is decent training for Cabinet and the prime ministership. CEOs, like ministers and prime ministers, are only as good as the information they receive. If the chief executive is in receipt of good information, he can make informed decisions. But in most respects the office of prime minister is so different that no private-sector role can prepare the lucky or unlucky occupant. If your landmark reforms stall, you can hardly pick up the phone to your deputy chief executive or general manager to give them a bit of a rev up. Instead, action usually requires a careful balance of Cabinet, parliamentary, public service and media considerations. The Sixth Labour Government struggled with these considerations in their first term, failing to convince Peters on legislating for Fair Pay Agreements or repealing the ‘three strikes’ act. In their second term, they failed to make the case to media and local government on the necessity of the Three Waters reforms. It was government by, in most cases, amateurs, mediocrities and no-hopers. Scarily, the incoming ministry seems to count an even greater number of amateurs, mediocrities and no-hopers.

This is where the government would normally require a strong personality — someone who can carry an inexperienced (or frankly useless) team. But Luxon is hardly that strong personality. If anything, it’s Peters and Seymour who, in three years’ time, might emerge as the only beneficiaries of what is likely to become the first unstable government of the MMP era.