Apr 23, 2025 Society

Towards the end of May 2022, a trial began in the High Court at Auckland. A fashion photographer and social-media influencer called David Chai Pegler was defending charges of sexually violating two teenage boys over a two-year period, starting in 2016. A previous effort to try the charges had been cut short after a week due to Auckland’s 2021 Covid lockdown.

Pegler, better known by the screen name “David Grr”, as he will be referred to in this story, had been acquitted in 2017 of sexually violating another man seven years earlier, after an initial conviction on the charges was overturned due to new expert evidence. This complainant’s testimony, however, was used as propensity evidence in the second trial, supporting the Crown’s case.

At the conclusion of the trial, the jury found Pegler guilty of five out of the six sexual violation charges and in October 2022, he was sentenced to nine years in prison. In 2023, he appealed against this conviction, unsuccessfully, and failed again at the Supreme Court a year later. However, he still could not be named in the media as he had another active case at the District Court, for violating another man.

In late 2024, Pegler pleaded guilty to that charge, and in January his name suppression was lifted, meaning Ella Scott-Fleming’s account of attending the 2022 trial can now be told.

—

The trial — Monday

It’s a cold and windy day in the middle of June. I’m nervous, so arrive at the High Court an hour early, wearing an ill-fitting vintage Armani suit jacket and a vintage Ann Taylor double-breasted linen skirt. Both items are borrowed. I sprained my ankle the week before, so I’m also sporting a moonboot. White shirt and one sensible Mary Jane, artist’s own.

It’s been raining on and off — the outside benches are too damp to sit on. I’m tucked under a brick alcove, vaping, when a familiar-looking man briskly walks past me and smiles. My heart stops. Perhaps I’m a pitiful sight in my boot and oversized suit jacket, sheltering from the rain. Or maybe I look chic? Either way, I hadn’t expected this man to meet my gaze so openly. Not while he was standing trial for, among other things, six counts of sexual violation by unlawful sexual connection. He looks very thin, thinner than I remember.

—

myspace.com, 31 January 2005. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

myspace.com, 31 January 2005. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

The back story, 2005

I had just started Year 9 at Western Springs College. The change from an all-girls Catholic intermediate to a mufti co-ed high school was jarring. Once loud and opinionated, I began finding it hard to put my hand up in class because there were boys around. The question of what to wear was no longer a crisis reserved for the weekends.

I squeezed my chubby, developing, 13-year-old body into pairs of Lee Supatube jeans, white leather Chuck Taylors and skin-tight Glassons long-sleeve tops, as neutral as possible. (Please don’t look at me.) The other students had had two years of mufti at Ponsonby Intermediate to learn what to wear — which, for them, seemed to be bright-green basketball singlets and/or barely-there miniskirts that showed off tanned, hairless legs. They accessorised with Nike sneakers and hand-me-down Louis Vuitton bags.

There was social media, but not the platforms we know today. First Bebo (username: Ella Kiedis); then Myspace. I spent hours after school drowning in other people’s pages and scouring their ‘Top Friends’ lists. They used black-and-white school photography for profile pics and had cool guitar songs blaring from their pages.

Indie rock was back. They sold 70s band T-shirts at Jay Jays. Out on the school field, teenagers were acting like it was the Summer of Love again, again, again. Kurt Cobain sunglasses, floral vintage shift dresses. Goths, emos and rockers all smoked cigarettes together. Sometimes the smell of marijuana would waft to where I sat watching, jealous. I missed the emo craze — too busy getting a wedgie from Sherryn of Papakura at St Mary’s — then, from the sidelines, I was watching indie happen without me, too. I just wanted to listen to the Black Eyed Peas.

But I did try.

Somehow, I heard about David Grr: king of social media; king of the emos; his last name changed to sound like ‘rawr’, the popular internet slang term denoting the sound of a dinosaur roar and an identifier of emos in the early 2000s. You couldn’t be on Myspace without clicking through to his profile eventually. His hair teased high, fringe styled sideways. With a number of ‘friends’. His profile pictures were all taken at an exaggerated angle, mouth twisted to the side coyly.

The emos hung out at Aotea Square and they were rumoured to be particularly sexually active. Maybe this idea came from their gothic Lolita style of dress, or their apparent fluidity of gender and sexuality. Emo boys with snakebite piercings, eyeliner and gauges in their ears played at being bisexual. At least, they did for the photos, adding the letters ‘FGT’ to the end of their profile names or wearing them on necklaces as a form of rebellion. Not that they were actually gay, necessarily, but the label was thrown at them as a slur, and they were flaunting it back.

People loved to bully emos. They were easy targets — they looked silly, they looked different, they looked ‘gay’. And New Zealanders, of course, loathe fame and success. This new way of being well known, ‘social media famous’, was annoying and unfair — popular for what?

Some of us were as envious as most people were derisive. Hungry, we wanted a piece of the pie. We were desperate to clamber into party photos. To be tagged in a Facebook album. To get free drinks. Among the kids around me, there was a common drive. We wanted to be known, but in this new, ironic, fluorescent way. We wanted our youth to be captured for the internet and our lives to mirror the rock-star-via-Myspace existence. We wanted to be indie internet famous, too.

—

thegrr.net, 5 October 2017. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

thegrr.net, 5 October 2017. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

The trial — Tuesday

My time at the High Court on Monday was aborted abruptly. The staunch receptionist informed me, wrongly, that as a member of the public I was unable to sit in on the trial. Disappointed, I went home to regather. But now I’m official — I’ve received an email from the ‘court crier’ that I’m allowed to attend and take notes with pen and paper. I moonboot through the carpeted hallways of the building to a small courtroom.

Justice Rebecca Edwards, the judge, is presiding above the rest of us. Below her, on the second tier, the crier and the witness box. The lawyers are shuffling papers below, setting up. The jury’s chairs are empty. I sit on the bench seats at the back of the room — I seem to be the only member of the public. I loudly whisper to a mousy-looking gentleman, “Am I allowed in here right now?” Terrified, he quivers: “I don’t think so? This is a name suppression case.”

The court crier approaches — she’s a short butch, my type — and tells me that I am allowed, but not until the jury comes in. I’m kicked back out into the lobby, where it’s just me, Grr’s mum and his brother. The brother looks awkward and antsy, the mother, tired. We sit in tense silence, waiting to be let in. I’d normally make chit-chat, but it doesn’t really seem appropriate.

When proceedings commence, Grr continues his testimony from the day before, under questioning from his defence counsel. The tone is relaxed. He answers the questions reasonably. He seems well spoken, nice. Gentle, even, if a little rehearsed. I believe what he is saying.

Thus begins my sinking feeling. I’ve been obsessing over this case for months. The legend of him — the idea that I grew up in Auckland at the same time as a predator, now accused of violating two teenage boys. Now, in the flesh, he’s a fully formed person. He looks smaller than I expected. Do I feel sympathy for him?

He is detailing a night out in 2017 with the second of his accusers, Mr B, then 18 years old. Bottles of champagne in the VIP room of 1885 and Ponsonby Social Club. Then the testimony moves on to more private information. The taking down of the man’s pants. Grr tells the court: “They were skinny jeans.” You know, the type that gets caught around your ankles. So he had to help. They took the pants off together, both conscious and consenting.

Grr’s manner changes as he recounts events. Oral sex is obviously his thing: “Can I suck your dick?” “Can I go down on you?” He offers that terminology easily. But as he goes on, he appears more uncomfortable. This is embarrassing, he says. He admits to asking, “Can I have sex with you?” You can hear the pleading in the question. This kind of sex is full of shame. Penetrative. He is denied.

“The complainant has claimed that you then licked his anus. Is this true?”

Grr bristles. “No, no, I don’t like that — I don’t like that kind of stuff.”

I become aware of his mother in the room. Oral sex may be okay, but licking the anus is rejected. He’s not into that, he says.

On a bathroom break, the court crier finds me by the sink, washing my hands. She informs me the judge has asked that I no longer take notes. She must not have anticipated the amount of detail I was cramming into my little notebook.

Crown prosecutor Sam Teppett is asking about similar conduct with another young man in 2010, the basis of charges Grr was ultimately acquitted of in 2017. A panel of High Court judges permitted the complainant’s testimony to be used as Crown evidence in this trial.

The prosecutor is quite handsome. Young and slim, with dark hair. A strong brow and sharp, intelligent eyes. But he speaks slowly, like a child.

Under cross-examination by the Crown, Grr’s demeanour is different. He is no longer obliging. He cuts off and disavows the questions. He is, well, defensive.

Teppett asks the defendant about working as a photographer in a popular bar in the Auckland CBD, where he partied with the complainant from the earlier case.

The two men would hang out backstage, the court hears. The photographer had a bar tab and would often buy his friend drinks.

If there were any left, Grr says, shrugging.

“And you would also go to the bathrooms to do drugs together?”

Yeah, Grr says, if he had them.

“And those drugs would be ecstasy pills?”

“Yes, pressed MDMA. Those were the only drugs going around at the time, I think.”

The defendant and the witness would often make out in the bathroom stall, the court hears. But on the dance floor, too. In plain sight.

The jury is flipping through a dossier of evidence. From where I’m sitting, I can see it’s thick with social media posts, party photos and Messenger screenshots.

“And we are looking at a photo from that night — that’s you and the complainant? It has numbers printed on it. Can you explain that?”

Grr says he was using an SLR (single-lens reflex) camera. With that type of camera you can set a date and time on the photographs. In my mind’s eye, I can see what the images must look like — bright flash photography, with the hint of a neon cardigan or bleached hair under a wide-brimmed black hat, big thick eyeglasses. Fringes now are glossy, shaggy and deep in a 1960s-meets-70s way, still somewhat swept to the side. Men still pale and thin with suspenders or Rosary beads.

According to the complainant, the alleged assault happened later, in a hotel penthouse apartment. The story is familiar. Grr says his accuser was awake, consenting. The complainant says he was asleep, or had been plied with too many drugs and too much alcohol by the perpetrator to reasonably consent.

In the morning, Grr says he woke up to the light streaming through the curtains. The witness had moved from his side and was asleep on the couch opposite, stripped of cushions.

“Did you think that was odd?”

Not really.

Grr gathered his clothes and shoes and slipped out. Downstairs, he asked the concierge to call him a taxi. Or he hailed one. He can’t remember how he got home — it was so long ago. There was no Uber back then, you see.

—

deersandbears.com, 10 October 2010. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

deersandbears.com, 10 October 2010. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

The scene, late 2000s

After emo, David Grr adapted and evolved. Rock bands became the centre of our socialising. Still in high school, teenagers rented out local halls to play under-age gigs. There are blurry photos of skinny boys, spider legs splayed; drunk, lying on the pavement, a bottle of wine in one hand. Maybe kissing another boy, in a confident, subversive way. Like Iggy Pop and David Bowie. For a laugh. You always had a bottle to yourself or, for sharing, a plastic goon sack of cheap wine. Mouth stained red, like a French poet. Baudelaire? Bohemian.

At a hall in the middle of town, under age, I watched girls with heavy fringes dance like they were electrocuted. They wore head-to-toe Mala Brajkovic — the most divine and expensive local designer of the mid-2000s. These were private-school girls. At my Catholic girls’ intermediate, I had only learned how to drop it low in denim-pleated miniskirts — how had these girls developed this 1960s free dancing style? I stood awkwardly at the back. My Nokia had been stolen. I saw the guy who did it, rifling through others’ bags openly. On confronting him, I felt guilty and embarrassed — he was brown and dressed differently from everyone else. I stood awkwardly between him and the bouncer, then shrugged and let him go.

Outside, my best friend was stuck on the phone with a boy (man) she’d met on a Beatles forum. She was Pattie Boyd and he was George Harrison. He travelled all the way from Ireland to see her. Turned out he was 20-something and ugly. She was not yet 15. She ran away from him at the Borders that used to be on Queen St.

I’m overdosing on nostalgia now, sorry. I feel a bit sick. But the point is, the five-year period from about 2006 was a time of ‘indie sleaze’, as it was later named. The aesthetics and choices of this scene pressed unhealthy norms into our young, developing brains — of under-age sex, wild parties and uncomfortable, sometimes illegal age gaps. Not to mention the adulation of whiteness and of thin, childlike bodies.

It was around this time that Grr made himself known as a party photographer. He was paid to attend gigs and take the type of bright SLR photography that was hot at the time. No doubt he was as much influenced and confined by this culture as I was. Perhaps for him, adopted by Pākehā parents from his native Thailand at 15 months, it landed differently. He seemed to aspire to the aesthetics of whiteness in recurring aspects of his online life, from emo, to indie, to his later stark minimalist photography.

Grr’s more problematic behaviour was able to go unnoticed in these environments — at least initially. Hidden amid the haze of cheap alcohol, the renaissance of ecstasy and the rise of a diabolical amphetamine, mephedrone.

—

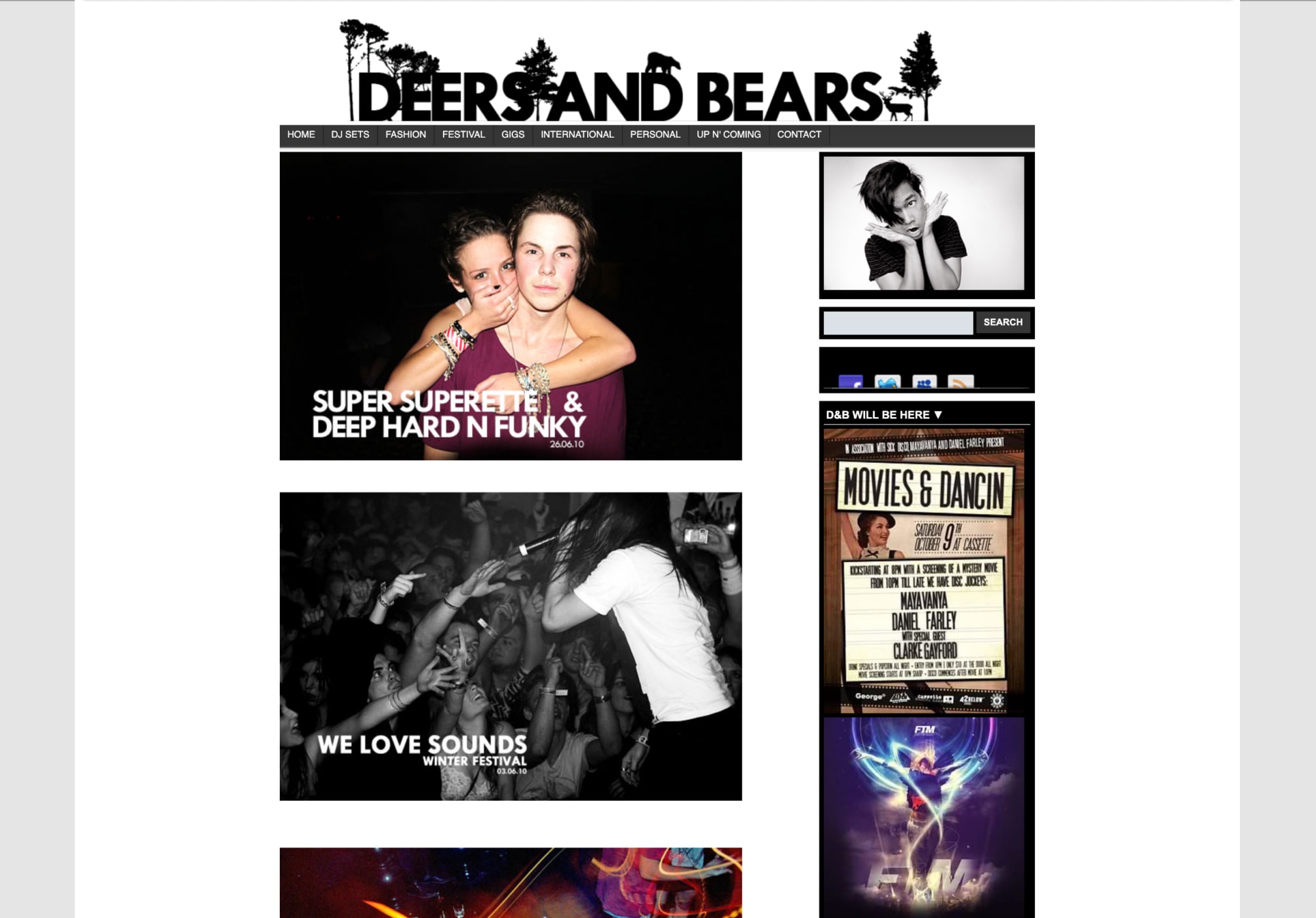

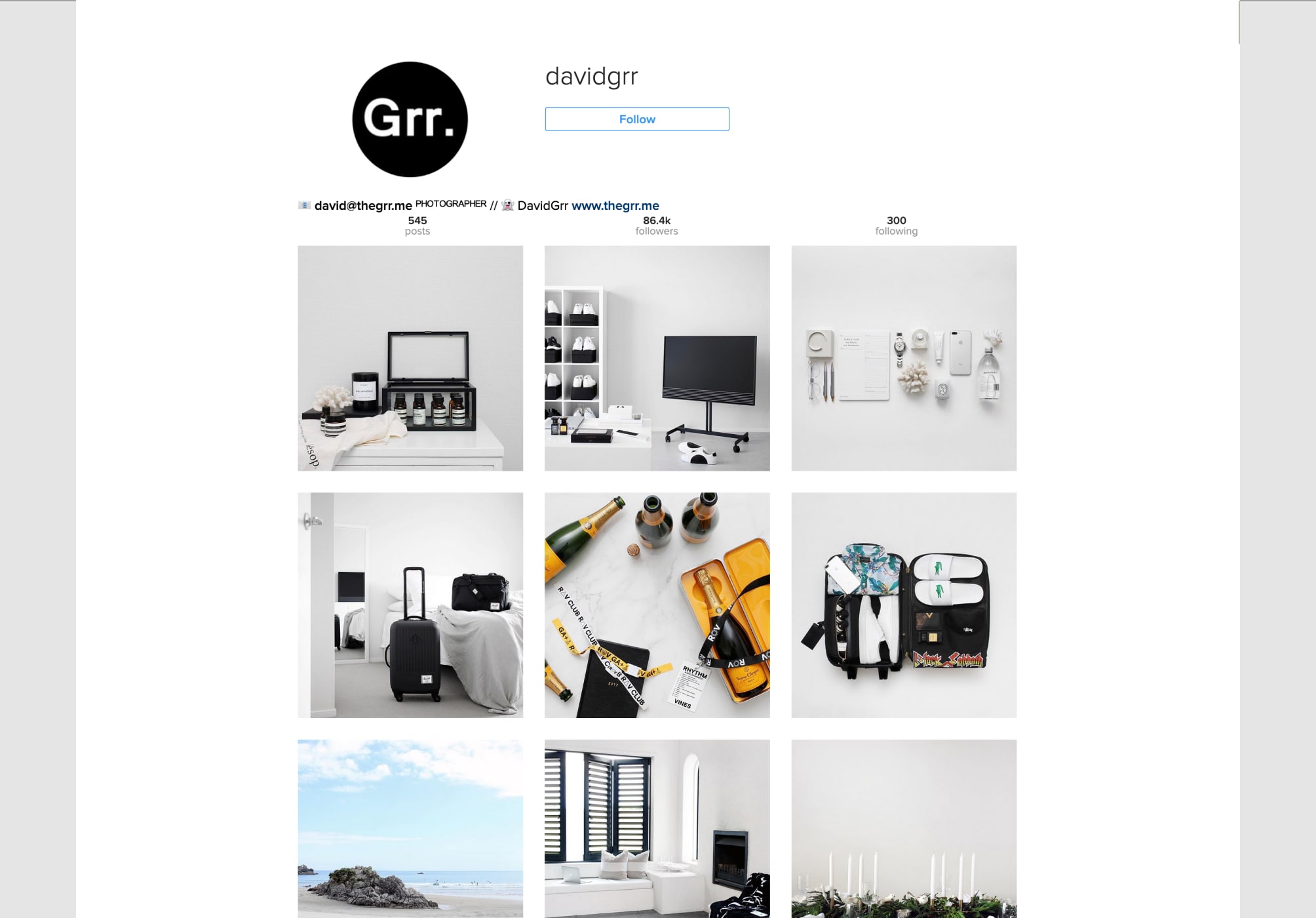

instagram.com/davidgrr/, 22 January 2017. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

instagram.com/davidgrr/, 22 January 2017. Accessed via The Wayback Machine

Influence, 2021 and 2016

When I found out in 2021 that David Grr had been charged, again, with sexual violation, I consumed his entire Instagram feed. I viewed his extensive saved stories, all categorised thematically. The stark black-and-white flat-lays, with a pair of shoes, a watch, a gifted sweatshirt, monsteras. An ad for luxury luggage, bags empty. Glimpses into his monochromatic home, each image fastidiously curated. It plunged me into a deep, dark depression. My flatmate found me on the couch with the sun going down. I hadn’t moved since I started. I should have left the house today, I moaned bleakly.

My sadness might have come from what I was learning about Grr, and the dark rumours surrounding him, but I am also a visual person, and I couldn’t help but conflate the content creator’s aesthetic minimalism with the emptiness of the man himself. His moral dissonance. The corruption of his soul. There are no people in these photographs. There’s no culture. There’s no love.

I imagined Grr’s social life: in a private member’s club at the Viaduct, bottles of champagne popping in all directions. Iced platters of oysters. Perhaps Max Key is there, as well as young, rich, blonde women. They all get drunk and nasty.

I wondered about his days. If he went for a run in the morning, before heading home to his flat, no one there. Cooking an aesthetically pleasing meal. Taking photos, maybe doing some emails, trying to drum up a brand deal. All the while waiting for his lawyer to call to give him an update on the charges laid against him.

Around the same time Grr was said to have violated the two teens, I was working as a catering waitress. In 2016, the fashion store H&M finally arrived in Auckland and there was an extravagant red-carpet event to celebrate the opening. I bussed for an hour out to Sylvia Park. The waitresses all wore white shirts and black pants; we had our makeup done upstairs at Mac.

The party was a big deal. The place was packed and relentlessly bright. My arms began to ache from carrying heavy square plates, one on each arm, sphinx-style, through the store. I was offering mini spring rolls, tiny savoury pancakes and prawns in little plastic cups. All the influencers had come. I recognised David Grr, there with his best friend, a small, hard-looking man with outrageous painted-on eyebrows. The friend fussed over something risky, maybe the prawn. Something with coriander? He decided to try it anyway. When I next circled back around, he beckoned me over. My arms were still pinned down with platters. I smiled my hospitality smile. He leaned in, grinning conspiratorially, and whispered in my ear: That thing you gave me was. So. Fucking. Disgusting. I had to spit it out.

He smirked at me to see if I got the joke. My smile faltered. Unable to defend myself, I drifted away.

—

The trial — Wednesday

Outside court, I admit to my friends that my feelings about Grr are becoming complicated. Perhaps because I’d been asked to leave the court while the victims gave their testimony, and hadn’t heard their side directly, some of the defence’s angles were working on me. Historically, queer people have often had complicated romantic and sexual relations with those who keep their proclivities secret. Both the victims in this case maintained they were straight and nonconsenting, a theme shared by all of Grr’s accusers.

Inside the court, cracks start to show in the defendant’s demeanour. I begin sensing a quiet rage in Grr, first when he is being questioned, hard, about his online communication with the younger of the two accusers, referred to as Mr A in court documents. Mr A was 16 at the time; Grr was 28. Sometimes flirtatiously, sometimes more coercively, Grr had been trying to get the teenager to send him nudes.

The prosecutor, Teppett, asks Grr if the complainant sent him a particular photograph. He holds it up. Rustling, the jury’s heads all turn to look at their own printed copy.

Yes, says the defendant.

The photo shows the 16-year-old shirtless, with no genitalia revealed. Grr’s eyes flick to the jury.

“That made you unsatisfied, didn’t it?” Teppett asks.

“Well, it’s a tease, that’s for sure. No one likes anyone who teases them.”

The ages of the victims offer a reminder of how skewed these relationships were. It’s something that Grr seems oblivious to or unwilling to accept. At one point he refers to Mr A, an aspiring influencer but still in high school, as a “street-smart individual”.

There’s the lying, too. He admits to initially lying to both victims about his age.

To groom them?

No, to seem more successful, Grr says. He claimed to be younger because then you have achieved much more at an early age, he explains.

The lies got bigger. Mr B, 18 at the time, says he was told that the influencer was 21, straight and owned his own home.

“When, isn’t it true you live at home with your parents?” asks the prosecutor.

“It is,” says the defendant.

You get an idea of the life Grr was wanting to inhabit, the life he appeared to live on his Instagram tiles. He was in love with Mr A, he says. But fantasy keeps bumping up against reality in an ugly way. Teppett puts it to the defendant that, in the provided text messages, the teen is saying that he doesn’t want any kind of sexual or romantic relationship with him. That he’s not gay.

From the screenshots of messages that have now become evidence, Grr has no choice but to agree.

I guess that is what you could take from this message, he says.

He’s reluctant to grant the fact, pausing to read over the messages before adding, “Well, that’s what he says.”

—

The trial — Friday

The next time I make it back to court, I learn it is the last day of the trial before the jury retires to deliberate. Any worry I have about missing Thursday’s evidence is relieved by Justice Edwards’ summing-up.

Some of the details I missed now sink in, and I am able to get a fuller picture. Mr A remembers waking up with a sore anus after a night out in 2016, and thought the accused had penetrated him while he was asleep. He was also suspicious that the defendant had spiked his drink. A year later, the teen says, Grr gave him a drug that made him lose all his faculties and he woke up to his abuser violating him.

The summing-up is over quickly and the jury goes off to decide. I slip away, relieved, thinking the deliberation will take days. I also feel deeply bleak. The courtroom is a lot more fraught and grim than I’d expected, going off what I had seen on TV. Not being able to do my usual exercise because of my injury doesn’t help either. I head to the Tepid Baths to swim lap after lap, until I am exhausted. Then burn it off in the sauna.

At home, clean, pink and feeling a little better, my phone begins to light up. Friends are sending me the Herald article — Grr has been found guilty of five of the six sexual violation charges. The jury also finds him not guilty of twice drugging Mr A in order to assault him and of blackmailing him for sex. In the article, Justice Edwards is quoted as saying the offender — his name still suppressed — will most likely be going to prison for a long time. I feel empty. I shut my laptop and go to bed.

—

The context, ongoing

Experts believe that sexual violence against men is under-reported because of the shame and forbidden weakness that constructed masculinity attaches to being sexually assaulted or disclosing a violation. (Sexual violence against women and children, of course, is also under-reported, for other reasons.) One serial rapist in the United Kingdom, Reynhard Sinaga, was convicted in four trials between 2018 and 2020 of drugging and sexually assaulting 48 men. Police believe he had raped or assaulted at least 206 men since 2015. Sinaga was able to offend so prolifically and for so long without being reported because of the specific silences and shame men hold around being assaulted.

Even writing about the sexual assaults of men can be harder and more complex than writing about sexual violence towards women. In New Zealand, the legal term ‘rape’, for instance, relates only to the vagina. Any anal violation is described by the longer phrase ‘sexual violation by unlawful sexual connection’. This charge covers oral sexual assault also.

On top of the existing problem of sexual violence and its climate of fearful secrecy, the rise of social media in the early 2000s created new ways to connect with others, new complicating intimacies. Old privacy norms and personal boundaries could now be broken down more easily. As teenagers using the technology for the first time, we did not know how to draw lines around social media and its ability to harm us. Loneliness could be converted into digital intimacy — sometimes positive, sometimes confused and synthetic. At best, the new media offered supportive connections; at worst it could lead to traumatic violation and manipulation.

From the beginning of social networks on the internet, David Grr was successful in constructing an online identity. Once being well known and influential became his job, he was able to use his profession as leverage to take what he wanted from young men who did not consent.

—

Further sentencing, 2025

The survivors Mr A and Mr B waited two and a half years for their abuser’s identity to be made public. Grr’s name suppression continued while he was sentenced, appealed against his conviction, failed on that, then tried to appeal to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear his case. He denied his guilt the whole way through. After his final rejection by our highest court he still could not be named, as another accuser had come forward, saying he had been similarly assaulted in the early 2000s. This time Grr pleaded guilty.

In January, Grr was sentenced for that historical assault. He appeared at the sentencing hearing via audiovisual link. “Disappointed doesn’t quite sum up how I feel that David did not come here today,” his victim said in court.

The court heard that, back in 2007, the man had been in Auckland for a music festival. After a night of drugs and alcohol, he and another person stayed over at Grr’s Remuera home. While they were all sleeping on separate mattresses, Grr came over to the victim. The man woke up to Grr violating him and rolled over, pretending to be asleep, while his attacker fled back to his own bed.

In his victim impact statement the man, now in his 30s, said the offending had consequences that “rippled through every area” of his life. After the violation, he said, he had pretended nothing happened, because it seemed “easier”.

Before passing down a 10-month sentence, Judge Kevin Glubb noted that what the defendant had said in the pre-sentence report was “in essence” still victim blaming. Nonetheless, Grr received some sentence reduction because of his age, cultural background and because he was suffering from PTSD and other mental health vulnerabilities.

Grr’s mother was not present at the sentencing, and the court was told she was suffering from extreme depression and anxiety stemming from the incident.

She’s obviously not the only one.

“We’re all broken in some shape or form,” the survivor stated. “Hurt people hurt people.”

For years, he said, “[I] convinced myself it didn’t really matter, it was only me that was harmed… not worth standing up for.”

Now, he said, he realised: “I do deserve care, I do deserve justice.”

Ella Scott-Fleming was the recipient of the 2023 Metro + Deadly Ponies Journalism Scholarship.