Apr 12, 2019 Society

The point of sharing things on social media is to have as many people as possible see and enjoy your content, right? So why is having a tweet go viral such an unenjoyable experience?

The first time I realised a tweet I’d written was going viral I was pathetically thrilled. After being slept on for so long, my amazing content was finally getting the recognition it deserved. I’d made it, baby!

Made what, exactly? Certainly not money. A certain amount of internet clout, maybe. For a day or so at least. Which I guess is what I wanted, otherwise I’d keep my incredibly stupid thoughts to myself instead of tweeting them in the first place.

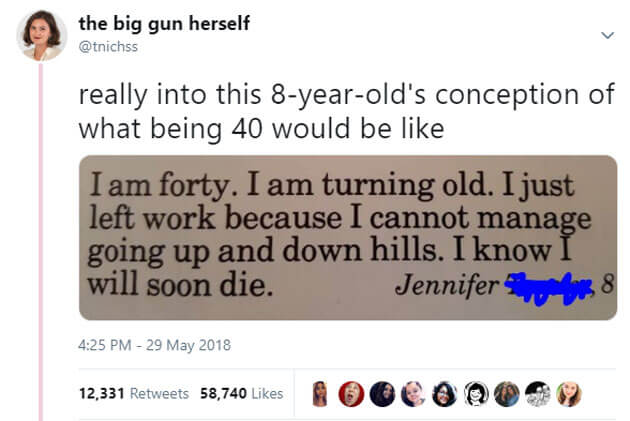

Virality is a contested term, but my opinion (and therefore the editorial stance of Metro) is that to be viral, a tweet must have more than a couple of thousand likes at the very least. I’ve had three tweets meet that threshold – the most popular wasn’t even really my content. I shared a funny image I’d seen on Facebook with a mildly amusing caption, expecting a handful of people I knew to like it. It retweeted 12,000 times including by the American author Roxane Gay and alt-right nerd Ben Shapiro, and beloved internet celebrity Chrissy Teigen was one of the nearly 60,000 people who ‘liked’ it so I now count her as a close personal friend.

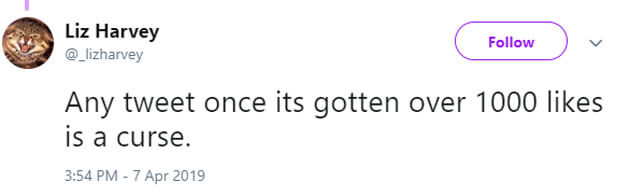

The experience each time followed the same arc of initial excitement (people think I’m funny!) followed by mild stress (do I have to reply to everyone?), irritation (stop explaining my own joke to me), over-analysing (why does anyone think this garbage is funny anyway?) and eventually muting the tweet and trying to forget about it (peace at last). Maybe there will be a few added hits of dopamine if a famous person or someone with a podcast you like interacts with it, but overall the whole experience seems more trouble than it’s worth. Most small-time NZ Twitters users I spoke to said when a tweet they’d written went viral, they too experienced a rush; a sense of validation that they were funny. They all ended up muting their notifications. I am keenly aware how ridiculous it is to whinge about, of all things, having too many people laugh at a joke you made online, but it’s fascinating to me that, given what you’re ostensibly trying to achieve on social media is maximum engagement with your content, it’s such a let down to actually succeed.

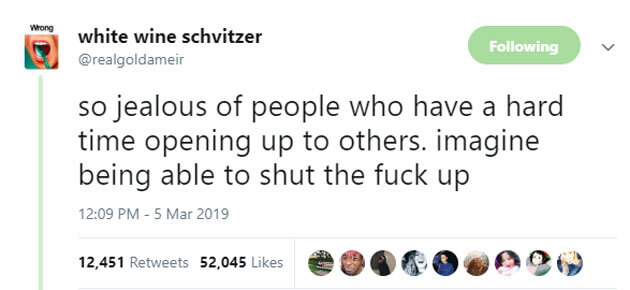

Gloria had about 150 followers when a joke tweet she thought of “while taking a dump” went viral last month, receiving more than 50,000 likes and 12,000 retweets. The popularity of the tweet, which reads “so jealous of people who have a hard time opening up to others. imagine being able to shut the fuck up[sic]” helped to just about double her follower count.

“I love the feeling of having to turn off notifications from people who don’t follow me. It makes you feel like people are taking notice of you. I rest a lot of my identity on being funny, so for that to be proven by people liking something I said, it’s a nice feeling.” The whole thing was incredibly rewarding, she said, but you have to take the bad with the good.

“There were a couple of things which really got me, like there were so many people being like ‘not me’ ‘this isn’t me’ ‘I’m the opposite’. Like yeah bitch, this is my tweet it’s about me. Make your own tweet.” Playfully rude (and downright obnoxious) replies from people she didn’t know started to annoy her, including people passive aggressively implying she must find it easy to open up because she had an easy childhood, a luxury they by comparison had not enjoyed.

“Number one, I had a really fucked up childhood, so I guess straight off the bat I’m like, you don’t know me. Are you seriously trying to flex on me with this? That’s something else I hate about Twitter, everyone’s got such a hard on for their trauma.”

Then there were the harmless but kind of lame replies – endless reaction gifs from the American TV show The Office and the like. “I was like oh no, lame people like my stuff! You’re not my target demographic, get out of here!”

Compared to the excitement of going viral though, the downsides were minimal and the experience was one Matthias would relish repeating. “Like it says in my tweet I’m an absolute attention whore. So whether it’s good or not it’s like people are liking my tweet, people are by proxy liking me.” She acknowledged it felt silly to say so out loud, but isn’t the quest for validation the whole reason we put our thoughts on the internet in the first place? She was the only person I spoke with who thought there was something gained from going viral, no matter how superficial.

Going viral caused fellow Kiwi Twitter user Jess McDowell to become concerned with how deeply she seemed to need the approval of online strangers. She quote-tweeted a Kanye West tweet about needing “access to more money in order to bring more beautiful ideas to the world” with the caption “me in the club transferring money from savings at 2am”. It got about five thousand retweets and double the number of likes.

“It gives you so much positive attention when you go viral because every time you check you have literally thousands of strangers validating you and reassuring you you’re funny. But then you start to overthink it, dissect it, feel pressure to go viral again. like with anything it becomes never enough or how can I get an even more viral tweet.” She recognises she was unhealthily obsessed with her Twitter presence at the time.

“It made me feel like… empty in a way because what does it really matter? Am I gonna start telling my coworkers a tweet I made has thousands of likes? I totally recognise now that none of it is important and you can’t use a website as a means of self esteem.” She is grateful for one thing – at least her viral tweet wasn’t the bad kind of viral. “Could you imagine going viral and people fighting and cancelling you [over a tweet].”

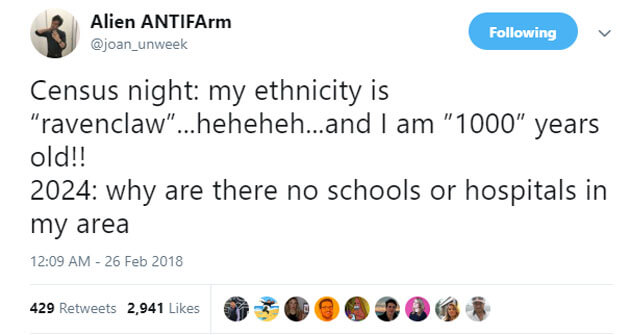

Aucklander Joe Nunweek said the same thing. “I’m just glad I’ve never been ratioed, a different and sobering experience.” In February last year a joke he made about filling in the census wrong as a joke went mildly viral, with more than 400 retweets and nearly 3000 likes. “It was a bit of a thrill but honestly I’m a lot happier when the 10 or so mutual followers I like and respect most on here [like] a tweet and that’s it.” Nunweek surmises that twitter fame is exciting in theory, but more or less hollow and unsatisfying in practice.

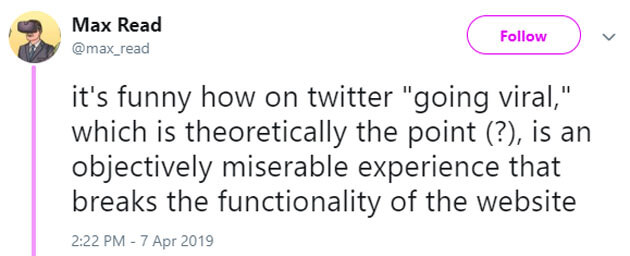

In a tweet which ironically went kind of viral itself, user Max Read wrote: “it’s funny how on twitter “going viral,” which is theoretically the point (?), is an objectively miserable experience that breaks the functionality of the website”. If this is the case then pressing question is of course, what on earth do we want from this?

I think it speaks to some primal urge for recognition – the same lizard brain decision-making process which prompts people to apply for a spot on a reality TV show, or act out in class to make the other kids laugh even though you’ll probably get in trouble and everyone may actually be laughing at you rather than with you. In the warped world of internet discourse, we often confuse a tweet with a lot of likes and retweets as having some kind of authority or inherent worth, which transfers onto the person who wrote it. When that person is you, the shakiness of that logic becomes very obvious. And yet. Nunweek acknowledges that despite knowing all of this, the temptation remains.

“Would I get a frisson of excitement tomorrow if I had a bad tweet go large? Sure.”

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the weekly email