May 7, 2019 Society

In the May/June issue of Metro, our regular columnist Leilani Momoisea handed her spot over to Shamima Lone, who wrote on the inner conflict she felt about Scarves in Solidarity, and her complicated relationship with the hijab.

The Christchurch mosque shootings brought up anxieties I thought I’d tamed with years of therapy. I immediately thought of my closest relatives and people I grew up around attending Jummah (Friday prayer). I thought back to attending Ponsonby Mosque every day until I got my period. I remembered being seven, pretending to be my own twin sister to the little white girl next door each time she saw me in my mosque outfit (a head scarf and robe) to avoid feeling embarrassed or changing her view of me.

The terrorist attack reminded me that racism is a continuum, that the racist micro-aggressions I experience every day are at one end and violent hatred is at the other. I felt ashamed for the years I’d spent with internalised racist ideals, trying to assimilate and reject parts of my cultural and religious identity. I felt layers of grief; a shared public grief and horror with the rest of New Zealand, the communal grief of the Muslim community, familiar grief recognised by people of colour globally, and also a private, disorientating grief tied to my identity and sense of belonging.

When a friend asked my opinion about Scarves in Solidarity and whether I’d be interested in helping with her fundraiser, we had a long discussion about my apprehensions towards white, non-Muslim women wearing a hijab for one day. I was concerned about the motivations people would come with — sometimes even I feel performative wearing one. Non-Muslim white women could wear a hijab for a day but never truly understand how it feels to be the target of discrimination and Islamophobia.

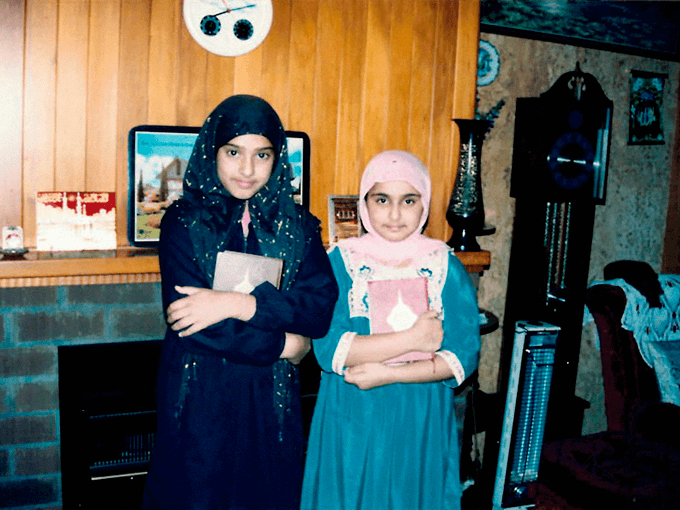

I started wearing a hijab when I was a shy and sensitive 14-year-old. I wanted to be invisible, but the hijab made me stand out. The first day I wore it, I was hyper-aware of how differently the world received me. Unfriendly faces stared at me on the bus, girls at school I knew well seemed unable to relate to me. People avoided me. I didn’t know anyone my age who wore one and I felt alone and ashamed. That day, I sought out my younger cousin and cried on her shoulder. (This cousin now confidently wears a full niqab, or face veil.) My parents, comfortable in their Islamic community, couldn’t relate to my experience. Their reassurances did little to offset the experience of being a woman of colour growing up in New Zealand in the 80s, 90s and 00s, let alone wearing a physical marker of my otherness on my head.

I wore a headscarf for 10 years. In the aftermath of 9/11, it made me an obvious target for Islamophobic abuse. As I got older, married, divorced, and moved away from the community and lifestyle, I felt confused and cowardly and rebellious about wearing my headscarf. Funnily enough, I felt the same emotions when I decided to stop wearing it. There was a huge shift in how both sides saw me; it was another major recalibration of my identity. I discovered that my very religious Nana (grandad) reserved his head pats and short chats about whether we’ve been praying and reading the Quran for his hijabi grandkids, and the rest he mostly ignored or didn’t know how to interact with.

Feeling satisfied with my discussions about Scarves in Solidarity, I agreed to help with The Love Movement’s #headscarfforharmony fundraiser [#headscarvesforharmony was held on 22 March]. It gave me an opportunity to help and provided me with an outlet for my grief, and renewed energy a week after the terrorist attack. When my mother arrived at the fundraising venue, Miss Crabb, she exclaimed her delight at me wearing a scarf — “Oh my! Is that my daughter? I didn’t recognise her! Doesn’t she look beautiful in her headscarf!” My first reaction was to cringe and freak out about my separate worlds colliding, but I was quickly flooded with relief, grateful she was safe. Whenever I go into the world with my mum and Nani (grandmother), I am painfully aware of people’s reactions to them. Unlike me, they dress in traditional, modest clothing and wear a hijab. They are usually oblivious, but I notice the gazes they receive: othering, curious, confused and sometimes hostile. After the shooting, I sadly feel rational in my paranoia about their safety.

The fundraiser collected more than $500 for the families of the victims. My mum and her hijabi friend loved helping women choose a scarf, discuss the fabric, and pin it on, talking about selecting colours and styles for different occasions. I think sharing their knowledge with a captive audience normalised and validated their experience and made them feel visible and special, which doesn’t happen often in a Western context. Or maybe it made me feel good to see them embraced, and I was just projecting my own narrative.

I wore my hijab until 11 that night, which ended at an event at Ponsonby Mosque. My skin, hijab and “Ask Me” badge turned me into someone with a simpler and more tangible identity that day. Muslims treated me as a fellow Muslim, and visitors saw me as a vessel through which to channel grief, sympathy and unconscious white guilt. I hugged a lot of women, received countless apologies (which I didn’t quite know what to do with), placed scarves on many heads, gave guided tours around my mosque, pointing out where the imam leads the prayer and where people pray. I explained how prayer is structured and is meditative and how distraction breaks your prayer and means you have to start again. I watched faces contemplate the horror of the massacre in such a peaceful space. I’d initially worried that these interactions would be pointless preaching to the converted, but the act of gathering felt deeply comforting, and each person I met had something different to ask or say, making space for a new dialogue. I also thought about how the same catalyst for change ran through all the stories I’d consumed about reformed white nationalists that week, about how change was only possible through familiarity, education and loving kindness from the very people they hated.

New dialogue has also opened up within my own family and the wider Muslim community. Many in my generation are speaking up about discrepancies they have felt but never before shared. For the first time, I’ve heard and contributed to collective conversations around feminism, teaching practices, leadership and judgement. After so many years of therapy trying to figure out how to be okay with the state of things, this new hope for progress feels like another calibration of my identity — albeit a less lonely one.

This column first appeared in the May-June 2019 issue of Metro magazine.