Nov 30, 2023 Society

The long, high screech of car tyres spinning against tarmac interrupted the story of how Sarbjit Singh had lost the use of an eye. “It’s started already,” he said, lifting his good eye to peer through the open roller doors of Walia Superette at a Karangahape Rd just beginning its Friday-night descent into the mess that alcohol and other substances make. It was some time after eight o’clock.

Singh, 57, speaks with a heavy accent that sometimes buries his words just too deep for understanding, and his short sentences are speckled with obscenity. He was telling his story from behind the dairy counter, perched under harsh fluorescent light, between a bushel of Chupa Chups and a stand of Whittaker’s. He arrived in New Zealand in 1989 as a 22-year-old from his native Punjab, India, first picking potatoes in Pukekohe, later laying concrete. It was in the latter job that, one day in 1995, a nail pinged into his left eye. He pulled it out himself, worried about too-long exposure to the poison of its metal. Now, the eye is clouded over by a milky white film.

“Farm, concrete layer, overstayer — then back to work again,” is how he characterises his time in New Zealand. The past 24 years of that work has been behind the counter at Walia. His children spent much of their childhoods in the store and its surrounds, roaming Karangahape Rd and looked out for by the locals. Now, it’s his grandkids who do as his own children used to, pulling the plastic-packaged products from the shelves and eating ice cream from the freezer.

Nights like these, when Singh works alone, are difficult. “I find it very hard,” he says. The crime — and the threat of crime — has never, he says, been this bad. “Not safe, brother, not safe,” he says. “It’s getting worse now, way worse.” Singh’s daughter, Angel Singh, 28, who finds the time to help out at the store when not studying at the University of Auckland, working her other job as an eyebrow technician, or looking after her two young girls, will now — if she ever has to be alone in the shop after dark — keep her mastiff/Great Dane cross behind the counter with her. “It is stressful,” she says. “It raises your blood pressure.”

Three months ago, Singh was behind the counter, alone in the shop. It was late. Angel had described to me the sixth sense you develop about the customers who will cause problems, and something about this man, as he walked to the back of the shop, had Singh bracing for trouble. The man came back to the counter, jumped on to it and brandished a knife. Singh grabbed a hockey stick in defence, and the assailant pulled back and fled, pursued by Singh before jumping into a car and speeding off.

Singh’s family worries. “That’s why I’m here a lot more,” Angel says. “I work all day long and then I come and stay here until six o’clock with my partner, because before it made me so sad saying ‘bye’ to my dad. I’m like, ‘All these things are happening in the community’.” In August, two people were shot on Queen St, one fatally; it came several weeks after Matu Reid had opened fire in a downtown construction site, killing two before he was killed himself. “As soon as I hear something,” Angel says, “I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh’. I ring my dad, ‘Are you okay? How’s everything there?’”

Angel says she’s begun to notice the way people look at her dad, as an older man, perhaps not as capable of defending his store and himself as he once was. “It does get stressful,” she says. “He’s here on his own.” Angel’s partner — he also works in the shop, on top of his job as a drain-layer — arrived and they left to fulfil their dinner plans on Ponsonby Rd. Singh settled on to his stool with the night in front of him.

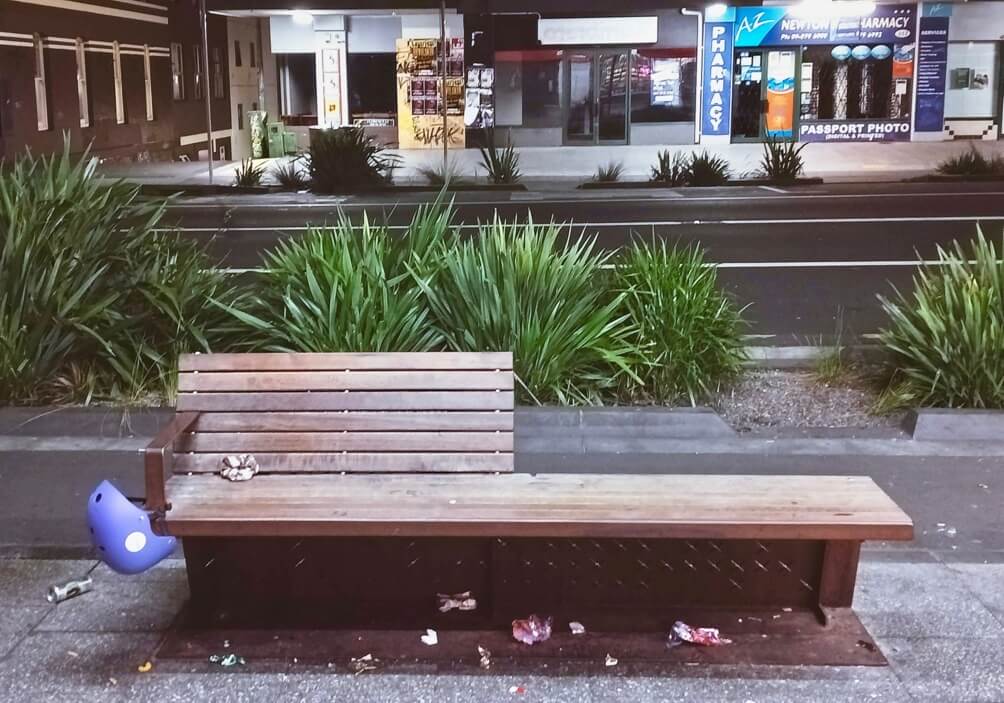

Later, Singh sipped from a pint glass of dark tea, the tags of two teabags entwined over the edge of the vessel. The league played on the screen opposite the counter; a game of kabaddi, a contact team sport popular in India, danced across the screen of his propped-up phone. His gaze flicked between the two sports. The after-dinner crowd was filtering through the store. A crowd of locals had set up a noisy residence on the bench seat outside, someone occasionally peeling away from the group to barter for how many pies they could get for 10 bucks or pick up a drink.

The trouble, Angel had told me earlier, rarely comes from the people she calls “the streeties”. “We know heaps of them — they’ve been here since we were babies,” she says. Occasionally someone will steal a packet of chips or a pie, but often they will return later with the money they owe and an apology. Newcomers to the area, some put into nearby emergency housing, with no relationship to the Singhs or the shop, make more trouble, as do those stumbling drunk out of bars and clubs. Singh guesses he loses “maybe 10 grand” a year in stolen goods. But he doesn’t bother to keep a record of those losses. “If it’s gone, it’s gone. Finished.”

The scent of cannabis sweetens the air outside the shop. Linger for long enough and you’ll be asked if you want to buy, or occasionally if you are selling. Singh speaks about the threat of crime with a kind of resigned anger. In response to the rising rates of crime and other anti-social behaviours, police patrols have increased by 243% in the central city over the past year, but Singh has little faith in the protection they offer — the police encourage him, he says, to ignore the shoplifting. “How do you run a business like that?” he asks. It’s only a pie, he says they tell him, don’t worry about it. “Oh yeah, that’s really nice. Today three pies, tomorrow six pies, the day after 12 pies.”

It’s irrelevant, he says, when I ask whether he ever enjoys his work. “If you go into business, you have to be doing it. No choice. Doesn’t matter if you like it or don’t like it.” The same work ethic that once drove him to fill sacks of potatoes for 50 cents a bag in the fields south of Auckland, saving every dollar he could, compels him now to keep his shop open through the night. It’s something he has passed on to his children, Angel says. “That’s the way he raised us. You need to work to get somewhere in life. You’re not going to get anywhere in life sitting at home on the couch watching a movie.” Singh puts in up to 120 hours a week in the shop. “I feel old, yes, but I have to do what I have to do. I can’t sit at home doing nothing.”

Later, revellers — replenishing their cigarettes, vapes or grabbing a restorative pie — came to dominate the stream of patronage. Next door at Orange Nightclub, a doorman dragged a beeping metal detector over incoming customers; the strains of karaoke came from Charlie’s Bar on the other side. At one point, red and blue lights bounced down the street. Outside, when I went to investigate, police cars and an ambulance had blocked the road to attend to a man who had been hit while trying to cross it; eventually, he got up, a patch of blood on his white shirt, and walked away. The road cleared, the crowd dispersed.

Back in the store, Singh rebuffed a woman who stopped in to ask if she could please store in his fridge the tray of meat she was brandishing. Outside, a streak of vomit traversed the bike lane, causing pedestrians to gingerly step over it and adding its thin acidic scent to the bouquet of the night.

The bench outside Walia

The night dragged on, the temperature dropped. Accumulated body heat escaped from the open doors of bars and clubs, their pockets of warmth fleeting relief from the cold. Nights were beginning to end — in arm-in-arm laughter for some, in glass-eyed stumbles for others, the story of the evening written in the stains on their jeans. I again joined the crowd outside Singh’s store, starting to grow with the approach of closing time. He had shuttered one of his store’s two doors. “Holy fuck, you still here?” he asked, when he noticed me reappear in the other. “Too much, mate. Too much.”

Police drove slowly past. Singh was busy administering to the late-night needs of the revellers, mostly pies and cigarettes. The club next door disgorged the last of its patrons, and I lingered as the waiting taxis slowly thinned the crowd. Often, Angel had said earlier, this is a dangerous time, with fights breaking out, disorder spilling into the shop, the strength of the glass windows tested. But tonight, all was calm. A quiet one, Singh agreed, and guessed that maybe the parties had been taken home to die natural deaths in front of the All Blacks’ World Cup game against Namibia, which was soon to start.

Singh has got one foot out the door, he says. He’s ready to retire. It’s just a question of getting the next generation — Angel and her siblings — ready to take over completely. “I don’t want to give it to them straight away. Tomorrow maybe they’ll fuck it up and that’ll be all my work the last 24 years for nothing.” In terms of crime, he doesn’t have much optimism that things will improve: “Nothing is going to change, brother. That’s the way they are now.” Politicians, he says, “are all bullshit at the end of the day”, but he thinks that maybe a return to a National government and the harsher sentences they want to implement might make his last years behind the Walia counter a little easier.

The first filaments of dawn were just beginning to streak through the sky. The night was over; Singh was turning off the lights. I bought a bottle of milk, shook hands, and left, walking through the cigarette butts and pie wrappers that littered the front of the store, down the deserted road to my car.

–

![]()