Jul 29, 2019 Schools

Whether fighting for action on climate change, plugging into mainstream politics or spending their lunchtimes exploring feminism, teenagers are embracing causes well beyond the stereotypical concerns of adolescence.

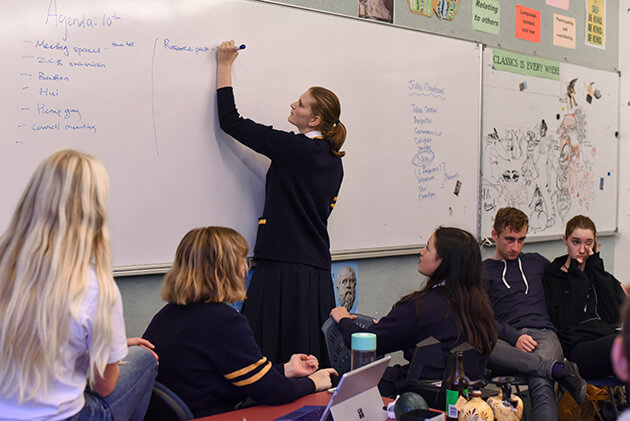

A classroom in Western Springs College is full at 4.30pm on a Monday, chairs haphazardly arranged in a circle. On them sit students from high schools all over Auckland, facing a whiteboard laden with scrawls. On one half, an abandoned Classics lesson plan; on the other, a bullet-point list of demands. Several students sit cross-legged in the centre, ripping tape with their teeth to spell #Wakeup on the back of neon hi-vis vests, in preparation for the upcoming climate-change strike. Voices overlap, until one yells out, “Who wants to talk to 95bFM in five minutes?”

It’s the week of School Strike 4 Climate’s second strike of the year, when thousands of students will stomp down Queen St after lying down in defiance on the paving of Aotea Square, a sea of youth in a mixture of uniforms and mufti. Placards and signs jut out or lie flat on their stomachs. Don’t Burn My Future. Denial Is Not A Policy. The Climate Is Changing… Why Aren’t We? Auckland’s organising group has spent months leading up to this in preparation: mobilising the participants through social media, working with the police and marshals, liaising with other relevant groups such as Generation Zero, agreeing on official demands, talking to the media, delegating roles and tasks, gathering megaphones, consolidating the messaging. No adult or teacher is present in these meetings; some of the students’ own schools have spoken out against them. They sacrifice school work, social lives and sport practices. They receive detentions. They chip in their own pocket money for promotion. They lose sleep. But it’s worth it. They believe it needs to be done.

School Strike 4 Climate is a world-wide campaign, with blueprints for its mechanisms lifted from activists in Australia, and inspired by the actions of teenage Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, who is credited with initiating the movement. Her speech at last year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference went viral, reaching the consciousness of high schoolers in what’s now called “The Greta Thunberg effect”. The New Zealand version has branches all over the country — its national co-ordinator, Sophie Handford, oversees the organisation from her hometown of Paekakariki.

I’m in the last dregs of the millennial generation. (Depending on whom you ask, my year could be considered the first of Generation Z — but that’s a boring argument.) I left high school six years ago. At my decile-10 high school in suburban North Shore, we didn’t have a Greta Thunberg. The closest I got to system-scale activism was when we all tried to “Stop Kony” in 2012, joining a call for the arrest of Ugandan militia leader Joseph Kony. We passed out leaflets in Browns Bay, the pages blazing with Microsoft Word art.

But there’s been a significant shift in youth activism in the years since I left school. “Fuck it, who cares, we’re all going to die anyway” turned into “Fuck you, guess it’s up to us to do something”. Young people have somehow managed to channel the doomsday news blasted through our phones and airwaves to energise themselves. Their politics is fully formed, statistics and justifications rolling off their tongues like a second language. And it’s not all the same politics, either. High-school activism looks different even within itself.

Some aim directly for system change, somehow managing to unite a diverse group of people behind one rallying cause, like School Strike 4 Climate. Forget about plastic straws and KeepCups, they argue. Let’s regulate.

“We were looking at countries around the world — like in Europe and Australia — basically got talking and were like, ‘Why aren’t we doing this?’” says Luke Wijohn, 17, of Western Springs College. The word then spread rapidly across social media, primarily Facebook and Instagram, where hundreds of schoolkids continually like, comment and directly message the group. “People talk down on social media, but that’s how we promote ourselves,” Sarah Paton-Beverley, 17, of Epsom Girls Grammar says. “We also sent out emails to all of the different schools,” adds Rebecca Kerr, 17, also of Epsom Girls. “Pretty much all 80 in Auckland. But we are always progressing — you make a friend and ask them if they want to come along.”

Media coverage shifted radically between the first and second strikes. “The first strike, we got quite a lot of negative media. People thought we were just kids,” Paton-Beverley explains. “Our intentions were questioned,” Gwyneth Parallag, 17, of Auckland Girls Grammar interrupts. Accusations of brainwashing and controlling parents only drive them on. “You want to prove them wrong,” Kerr says. “You want to show them, well, actually, we do take this seriously.”

It seems some still have to learn that their views will be challenged, however, and that not everyone believes in their movement as much as they do themselves. Paton-Beverley and Parallag were caught off guard on TV3’s The AM Show by a statistic about New Zealand emissions that neither of them was prepared for. “It’s such a shame when they try to do that,” says Paton-Beverley. “They’re undermining the movement and undermining us as youth and all the work we’ve put into this.” Or maybe just asking the kinds of questions that activists need to have answers to.

If that was a frustrating encounter, the group could claim its first victory on the afternoon of our second meeting, when Auckland Council declared a climate-change emergency. That was one of the four core demands School Strike 4 Climate had marched for.

Kerr, Parallag, Paton-Beverley and Wijohn all bunked off school to speak at Auckland Town Hall, and hear the city’s councillors speak in return. Though the victory signals a willingness to change, they know action isn’t guaranteed.

“It’s a way for us to hold them accountable,” Paton-Beverley clarifies. As she talks, nods from the other members of the group punctuate her words with encouragement. In fact, it’s like that the entire time. There’s a steadfast adherence to inclusivity in the spaces they afford each other’s speech, a layer of unspoken trust. Even if individual ideals may differ, they’re united by the endgame.

When I ask why young people are connecting so strongly to this issue, there is a dumbfounded five-second silence followed by a small chuckle in disbelief.

“It’s our future!” is the first cry, coming from Kerr. “That’s how fast climate change is affecting our planet. In decades, we’re only going to be, what, halfway through our lives. I think seeing it progress so fast is really, really scary. We all have such a love for our country and planet, so why wouldn’t you stand up and do something?”

Wijohn adds, “It’s less personal for adults. They’ll have the luxury of dying of old age, surrounded by families or whatever. But for our generation, on the path we’re heading on at the moment, we’re likely to die of climate-change-related causes.”

“Our strikes are really focused on system change over individual change,” Paton-Beverley says. “That’s why we created the national demands. They’re all focusing on things the government needs to do. It’s quite frustrating to watch little action being taken. We are a First World wealthy country and we have all the resources we need. Like, we have a massive agricultural economy but agriculture makes about 49% of our emissions. There needs to be a change there and it needs to happen now.”

Kerr believes public support is needed to force politicians to make changes. “They’re politicians. They want to get re-elected.”

The group has had meetings with Mayor Phil Goff and MPs, but conversations and dialogue aren’t action.

“A conversation is wonderful. It’s lovely to open up the conversation,” Paton-Beverley says. The words border on sarcasm undercut by frustration. “But we need action.”

Ben Fraser, 16, is trying to carry out action from the inside. Deeply involved in local politics, he’s as articulate as any current MP in Parliament. Diplomatic, too. When I ask him how our current government is doing, he’s got an answer ready in his back pocket. “I think our government is doing a really good job. There are always challenges to progressive change, but I think we’re seeing the change we want to see. Like, take indexing benefits. It might not always be the headline-grabbing policy that’s going to attract attention, but it’s going to make a massive difference in the lives of everyday New Zealanders.”

Fraser is a Year 13 student at St Kentigern College — a private high school in decile-10 Pakuranga — has a cat named Jones who “watch out, will attack”, and plays a little squash. Also, he’s an activist. He’s the deputy chair of the Howick Youth Council, a member of the youth board for I Am Hope — Mike King’s mental health organisation — and holds several roles in the Labour Party (chair of its “southern hub”, sits on its local government committee for Auckland, is secretary of the Pakuranga electorate committee, and is a member of the party’s Auckland northern regional council). He dutifully reads what’s on the itinerary for him this week, including fundraisers, campaign meetings and networking opportunities. “Last week, I had about 13 events on.” No wonder, when I see a keyboard and guitar and ask if he plays, the reply is, “I play both badly.”

One day he could be running a youth summit for high schools around east Auckland, on another pulling together a petition for the New Zealand Qualifications Authority to put a student on its board. Maybe he’s running a campaign endorsing a T2 bus lane on the Pakuranga Highway, or creating a workshop to promote CV literacy. He’s currently in the process of starting a mental-health initiative aimed at friends of young people going through a hard time, suggesting how to create strong support networks for them.

His motivation is underpinned by a self-awareness of his own privilege. “I started to realise it when I was about 12-13 that my life of privilege was not something that everyone else had. It sparked a feeling that I needed to do something, utilise all the opportunities to try to give back and empower others.” You get the feeling he’s asked this a lot. There is no halted stuttering of a 16-year-old, or cynical, off-handed quip. Instead, Fraser says things like, “I was just talking about this on a podcast the other day…”

Fraser is giving nothing to existential dread, an impressive enough feat in an era saturated with internet nihilism. “The fundamental questions of equity are not something we can think about and go, ‘We’re going to solve this’. If we do that, it’s just going to be so big, so overwhelming, and we’re not going to do it, because it’s just too much work, too hard. So I like to think that for anyone, whether you’re a high schooler or adult, it’s about identifying smaller challenges and focusing on achievable goals.” But accessibility is the challenge, he says. “I think what puts a lot of young people off is, for me to go out and do advocacy work in local government, I have to sit through long, boring local board meetings. You’ve got to read massive documents that are 300 pages long to get to the piece of information you need. That’s not accessible for young people.”

That isn’t accessible for most young people, it’s true. But getting involved in local politics isn’t the only way high schoolers are capable of enacting change. Giving up your time to organise an immense city-wide strike — also not accessible for some — isn’t the only other option, either. Fraser hints at it himself: identify smaller challenges, focus on achievable goals.

At high schools around Auckland, small, school-level activist groups gather in classrooms during their lunchtimes, lounging at desks, filling the empty air with their discourse, curating and asserting their evolving identities.

It may not trigger any concrete change. But I think about what a difference it would have made to me in my earlier years to have been able to talk about social issues in real life rather than just absorbing toxic, sometimes-misinformed hot takes while incessantly scrolling through Tumblr, anger spilling over in the most unproductive of ways. I might have been a more tolerable teen if I had something like Western Springs College’s intersectional feminist group, a safe space to bounce ideas and explore lofty concepts until things are made just a little less overwhelming.

“We consider ourselves an intersectional feminist group rather than a feminist group,” Sienna Davidson, 17, says. “It makes room for inclusivity for all, and I think eliminates the fear some people have — we’re also for men, women of colour, transgender people.”

Davidson and Hattie Salmon, 17, are the leaders of Western Springs College’s intersectional feminist group, Rights! Right? Along with two other students, Lilly Raukawa-Heslin, 16, and Sofia Roger Williams, 14, they give up their lunchtime to talk to me.

Their “discussion-based” meetings revolve around a range of topics, from sexual assault and consent, to historical feminist movements. “At our age, everyone’s exploring and learning. It’s that pivotal point where people need to be guided in the right direction,” Salmon says. Eventually, though, the meetings became an echo chamber. “We want to focus on fundraising now, because we realised it was the same people talking about the same things every time. For example, we’re starting a fundraiser for Women’s Refuge soon.”

Observing the ways gender affects life experience was enough to make them want to do something. “As a young woman coming into high school and starting puberty, you’re getting into all of it. By the end of your journey, if you’re a girl, you’ve definitely had a friend that’s had a terrible incident. You definitely know of a man who you know to stay away from.”

Social media has played a big part in this awareness — seeing the way female celebrities get treated in comparison to their male counterparts on the world stage proves it happens to everyone, and everywhere.

Feminism, the students repeatedly assert, has changed. It has evolved and mutated over the years — even as recent as the past two. Despite the #MeToo movement, there is still a reluctance to fully own the label of “feminist”. There’s an antagonism towards the group, and feminism in general, some of which is expressed within the school itself. “We had people running past going, “Who’s the man in charge?”

Salmon continues, “It became harder in the past year for us to get people involved. It felt for me there was this shift where suddenly feminism was uncool. When we first started out, people had been interested.”

“Right around the #MeToo movement,” Davidson adds.

“Yeah, then people just stopped turning up. I think it’s partially the internet.”

Specifically, the rise of certain right-wing voices. Raukawa-Heslin pipes up, “I think it was a lot of the Ben Shapiro stuff — he started talking and coming out more on social media, like with his comments on abortion.”

“Jordan Peterson.”

“Yeah, I think that’s when everyone kind of shifted and was like, “Do I know what feminism is?”

“It became scarier. Now there’s this grey area. But it was definitely trendy.”

“I can remember T-shirts from Topshop being like, ‘FEMINIST’.”

“It’s just like any other trend, it goes out of style. And that’s really sad, because it was so empowering for a while.”

Roger Williams, the youngest of the group, asserts there’s still a lack of education about what feminism really is. At 14, most of her friends don’t know what it is — but most definitely know the stereotypes surrounding the feminist label. And, Davidson adds, it can be hard for people “coming from a place of privilege” to get it. “Because how are they going to know what’s wrong in the world?”

Groups like this, Salmon says.

There’s still the business of schoolwork, sports teams, boyfriends, girlfriends, family pressures, other activist pursuits, part-time jobs, walking the dog. The School Strike 4 Climate group laughs steadily when I ask if all the preparation impacts on other parts of their lives. A chorus ensues: “So many hours.” “It’s a lot of pressure, a lot of stress.” “We get really behind on our schoolwork, and by the time the strike is over, you have to spend a week recuperating.” “It just needs to be done.” Meanwhile, Ben Fraser trusts the support system he’s built around him to tell him he needs to take a break, and says it would be impossible to juggle a part-time job on top of his activism.

What has changed between my generation and this one? Part of it might be that it’s cool now. You can see that in the way corporations have figured out how to package it into their marketing, and the way activism plays out on platforms like Instagram. But, more than anything, I think Generation Z have figured out that they can make people listen to them.

They can see the way forward. And they’re moving.

This piece originally appeared in the July-August 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Young & restless”.