Nov 23, 2018 Schools

A new exhibition, Ex Libris, celebrating three specialist and soon to be closed University of Auckland libraries opens on 24 November. Here, in an essay, architect Lucy Treep hones in on the history of one of them: the School of Architecture and Planning Library, evaluating its immense impact from 1925 to now.

Alongside the books from New York, the new School of Architecture library contained works donated by Professor Knight, who gave nearly all of his own books, and volumes from the Auckland branch of the Institute of Architects, who permanently loaned their books to start the library collection. These generous donations are symbolic of a defining aspect of the history of the library: the collection has been considerably enriched by a significant flow of donated works from staff, current and past students, architects, and interested members of the public. From 1951 (till the 2000s when the Bulletin was reduced in detail) the library produced a yearly record, the Annual Library Bulletin, which reliably contained a lengthy detailed list of donors and donated works over that year. Frequently these works numbered far more than those purchased by the library that year. These donations speak of the regard held for the library, and the integrated nature of the School of Architecture, its students and staff, the library, and the wider profession.

Professor Knight was convinced of the value of the library. For its first years it was housed partly in the main library, then in what is now called the Old Arts Building (or the Clock Tower Building), and partly in the Professor’s outer office. But he could see the growing library requirements of the School. One of his early studio programmes, for second-year students in 1929, reads:

A gentleman has bequeathed to a University School of Architecture a large collection of books on architectural and related subjects which it is his wish should become a nucleus of a library for the use of students of architecture in particular and of the Fine Arts generally…

The total area he specified was 4,000 square feet.

To help manage the growing library, top students were engaged as part-time librarians, for either a small salary or free tuition. The first was Tibor Donner in 1932. By 1937 the School library had approximately 600 titles of, what Knight called, ‘up to date works’. By 1947 there were 1750 titles and 200 more were on order. In his 1947 Memorandum Upon Architectural Education, Knight says,

The value of a comprehensive library in architecture and related works needs no emphasis except that it should be noted that the Auckland University College School is the only School of its kind in New Zealand and its library responsibilities are therefore greater than in some other schools. Research work can be encouraged by the creation of a first class library. It is indeed necessary for it’.

That year the library finally got its own space, when the School moved into a series of old steel army huts on Symonds St, near where the School now sits. The move, though long anticipated, was the first of a number of shifts. Over the years the library, and the School, repeatedly outgrew its allocated spaces and juggled with available infrastructure, until finally both were housed in the purpose-designed and built School of Architecture and Planning complex they still occupy, with the library at its heart.

The move, in 1947, to finally fully house the library within the School of Architecture was a great hit with both students and staff. The School of Architecture ‘firmly regard[ed] this Library as an integral part of the School’s life and teaching’. Architect, Sir Miles Warren, who was a student at the School from 1949-51, recalls,

The greatest delight for me in coming to Auckland was to discover the school library… There were the usual grand monographs on Arts and Crafts, Edwardian architecture, Victorian books, A.W. Pugin, heavy tomes on Beaux Arts design theory and history… I recall only a few books and magazines on modern architecture. There was, of course, Frank Lloyd Wright; The Modern Flat and The Modern House by FRS Yorke… three copies of the Architectural Review on Swedish architecture… the new Mies van der Rohe; and the first books of Le Corbusier. The first three of his eight-volume Oeuvre Complete arrived at the school one after another and quickly became our generation’s bible, each plan and illustration eagerly devoured and committed to memory’.

The appointment of the School’s first full-time, permanent librarian, G. Lilian Cumming, in 1950, confirmed the success of the new library accommodation. Lilian Cumming was the first of three long-term and highly influential librarians-in-charge, whose strong personalities sequentially shaped the library over the next 65 years. Lilian Cumming, Christina Troup and Wendy Fletcher (later Garvey) all contributed to the development of the School of Architecture (and Planning) library with warmth, good humour and, sometimes, military precision. They all seem to have been in agreement that, as Lilian Cumming wrote,

The main difference between a Special Library and a General or Public Library is that, while all professional and technical procedures would follow a basically similar programme, the Special Library does everything that the other always do, only ‘very much more so’ for a smaller field and for a more exacting clientele.

Under the attention of Lilian Cumming, integration of the library with the School tightened. In 1951 the library inaugurated the showing of architectural films. In 1952 the School’s collection of 2,000 glass slides, initiated by Professor Knight, was housed, catalogued and cross-referenced by the library. Within a few years this developed into a large collection of 39mm slides. Mrs Cumming held the key to the dark room, set up by Professor Knight for staff and students. A gramophone player was purchased, to listen to, for example, a set of records of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Gold Medal Speech. Mrs Cumming gave a talk on the use of the library to all first year students. She also instigated the sending of a New Year card to new students, and a hand-made Christmas card and letter to final year students. A Library Bulletin was sent out four times a year, to staff and members of the architectural profession, and an Annual Bulletin for the previous year written each January. Mrs Cumming always referred to the library with a capital ‘L’.

By 1957 the steel huts housing the School of Architecture were creaking under the weight of growing student numbers, and the library was moved next door to ‘Fernleigh’, an old house on Symonds Street. The library occupied the ground floor and basement, and the upper floor housed the new Department of Planning. ‘Space was almost doubled – from 800 sq.ft. to1500 sq.ft. It was a great relief.’ Drawing on Sir Henry Wooton’s formulation of architectural virtues, Mrs Cumming said of the new space, ‘in place of a rapidly cramping steel hut, 20ft by 40ft, we now have a spacious room, light and airy, with high and elegant kauri ceilings… I think we can safely claim that the new Library most happily fulfils those requirements of basic Architecture – ‘Commoditie, Firmness and Delight’.

By 1963 the library was on the move again, to another elderly building, ‘Old Elam’, on the uphill side of the School of Architecture. At the time of the move, Mrs Cumming noted, ‘the library is “in transit” – like Mahomet’s coffin, between the “heaven” of our new quarters and the “earth” of our Fernleigh home – where, however, we have been very happy during the last six years’. Though this was, from the beginning, a temporary home due to the new motorway extension planned to sweep under it, alongside St Pauls and down to Wellesley Street, the library remained in ‘Old Elam’ for 11 years. It was considered ‘commodious’ and had an ‘individual atmosphere’, but Mrs Cumming did note the ‘blocked drains, roof leaks and rodents [contributing to] time consuming crises and problems’.

In 1968 Lilian Cumming retired. Her last major act was to write a comprehensive School of Architecture Library Manual, to standardise library procedures, and enable continuity of practice. In the Manual, she sets out the relationship of the library with the School:

The Architecture Library finds that its work is closely concerned with all phases of the curriculum, with the study material required and with certain corroborating visual aids and further, not only with all phases of the present curriculum, but with the forward reaching philosophies and the imaginations of the future. As one lecturer has said, of all the aids to study that a student must employ, the Library is the largest… the Architecture Library is an integral part of the School.

The Manual is detailed and charming, and speaks of an ordered world. Many years later, Senior Librarian, Bruce Howie, would take mischievous delight in reading out loud to other staff the section titled ‘Personnel and Personality’:

What an assistant does in her own personal time, is of course, entirely her own affair. Nevertheless we do not live in a social vacuum, and so as Librarian I do take an interest, without in any way meaning to pry, in my staff’s personal background. However, our first duty is to our employer, the University. I would strongly deprecate any outside activity that would reduce an assistant’s efficiency in her work (I am thinking, particularly of such things as sun bathing all weekend and then being unable to work properly during the following week!).

On Lilian Cumming’s retirement, Christina Troup was appointed Architecture Librarian. It was a momentous time all round. The year 1969 brought change in the established order in both the School of Architecture as well as in the library administration. Allan Wild took office as the new Dean of the School, and Ivan Boileau was appointed new Head of the Department of Town Planning. Christina Troup began her new job with an entirely new library staff.

Despite all the changes in management, life in the library continued smoothly. As capable assistant librarians left, more joined the library. In 1972-3, Maurice Gee was one of the library staff. Quarterly bulletins as well as the Annual Bulletin were circulated each year conveying information about the library and the School. For example, in the 1972 Annual Bulletin, Christina Troup wrote:

Four bulletins have been distributed [this year] to staff, students, libraries and practising architects. Each number of the bulletin contains an article by a staff member on some aspect of work at the School:

- The Vernon Brown Collection of architectural drawings in the library, by Mr FH Beckett.

- The late Professor Cyril Roy Knight by Professor RH Toy.

- Improvement of Housing in Freeman’s Bay, by Mr VL Terreni.

- Changing to Metric Units, by Mr DG Stevens. These contributions enable readers to keep in touch with School activities and research.

Anticipating the demolition of ‘Old Elam’ the move to new accommodation in the basement of the Computer Sciences Building (now Building 409) gained the library much needed space, but at the cost of atmosphere. Miss Troup noted that ‘among students there lingers some nostalgia for the old days and ways’. However, work was about to start on the new School of Architecture and Planning complex, and staff and students knew the library space was temporary. At this time a major historical resource was added to the library holdings with the donation of the Sheppard File – a collection of documents, records, drawings, photographs, journal and newspaper articles relating to New Zealand architects and buildings from 1830 – gathered by Mr F G F Sheppard, the former Government Architect, from 1923 to the time of gifting in 1975.

Christina Troup retired from her position in the library in 1976, and assistant librarian, Wendy Fletcher (later Garvey), was promoted to librarian. On her appointment she was visited by Lilian Cumming (wearing a top hat), who was obviously still deeply interested in ‘her’ library. In 1977 Wendy was joined by assistant librarian, Bruce Howie. With a brief break in 1991 (after she was badly hurt when hit by a car while crossing a pedestrian crossing), Wendy, ably assisted by Bruce, guided students and assisted staff in all library matters for the next four decades. In 1979, the library moved to temporary premises one last time – to the level 3 studio space in the Architecture Building. In the 1980 Annual Bulletin, Wendy Garvey wrote:

First complete year in the new temporary premises in the Architecture Building… the area allocated to us works extremely well as a library… Being in the same building as the departments of the faculty which we serve has led to far greater utilization of the collection by those departments as shown in our issue figures which are 6,000 up on the 1979 figures.

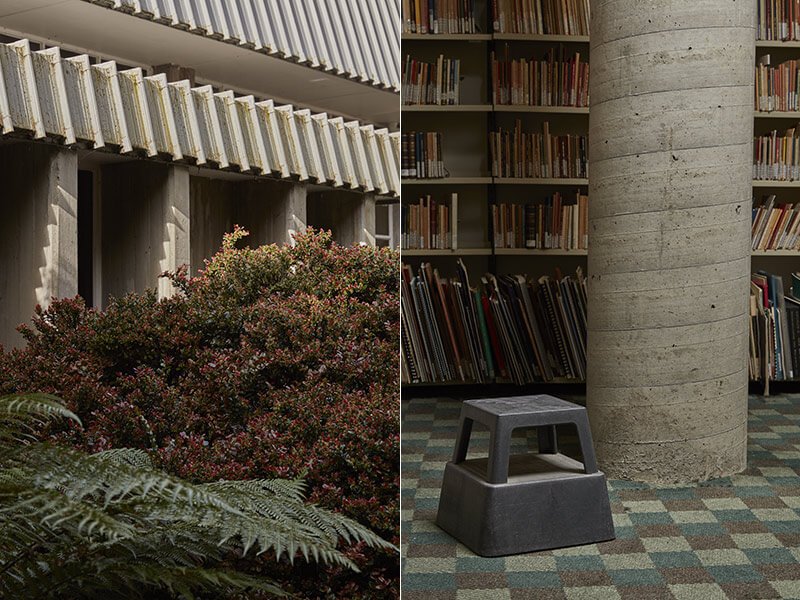

The success of the space on level 3 didn’t dim the pleasure when, in December 1981, the library finally moved into its purpose-designed and built home across the architecture courtyard:

At long last we have a permanent home for our collections, and an excellent area for students to work in – all in all we are delighted with our new home… It is a marvellous sensation after much making do (albeit in pleasant surroundings) to have a place for everything and everything in its place.

The move coincided with a substantial increase in usage, even above the record figures of the previous two years. It seemed the close proximity, and generous spaces were appreciated by library users. A review of the School of Architecture in 1986 reported that the library was regarded as one of the best architectural libraries in Australasia.

Donations were still regularly received. The collection of architectural furniture held by the library was boosted by the arrival, in 1989, of a pulpit designed by E. A. Plischke, used by the library as an atlas desk. The library continued to be a showcase of high-quality student work, with architectural models and prize-winning art works lining the walls, the ends and the tops of all the book stacks. The archiving of accumulated architectural material, initiated by Christina Troup (whose early understanding of the importance of this material was critical), and continued by Wendy Garvey, was formalised in 2003 by the establishment of the Architecture Archive, a major addition to the library, and a national resource. Originally a collaboration between the Faculty of Architecture, Property and Planning, the NZIA and the library, it was launched with an exhibition, ‘The House’, at the School of Architecture. Sarah Cox, the archivist, continues to document and manage the collections under a joint funding agreement between the School of Architecture and the University Library.

An on-line circulation system had been introduced in 1996 and gradually digital systems changed the world of library use, as with all other worlds. Access to the library and its holdings has expanded with the arrival of digital tools. The specialist librarians, essential to the success of the Architecture and Planning library, facilitate all levels of use of the library.

In 2015 Wendy Garvey retired. She wasn’t replaced, but Kirsty Wilson, manager of the CAI Libraries, took over some of her tasks, helped by Caroline Foster-Atkins and Sarah Cox. In 2018, despite the library recording the highest level of use of all the specialist libraries, and despite the continued critical engagement with, and enjoyment of, the books, journals, maps, artworks, drawers of measured drawings and watercolours, models and architectural furniture and much other contained within, the closure of the library was announced.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the? weekly email