Jun 30, 2014 Schools

Among primary schools in Auckland, the spread of achievements doesn’t correlate with deciles. Mangere’s decile-one Viscount School is proof of that: its results are spectacular. How does it do it?

Above: Pupils Andy Toia (left) and Ongolea Tangi.

This story was first published in the June 2014 issue of Metro.

“Hi, miss! Are you looking for someone?” Two girls — smiling, dark-haired, brown-skinned and neatly dressed in uniform red — introduce themselves as Raylanny and Y’Quesha. They lead the way to the foyer’s unattended desk. My new friends assure me, “Diana and them will be here soon.” They offer me a seat and continue on their way. Through the closing door comes, “Bye, miss… have a lovely day.”

Viscount Learning Community is a decile-one school in the heart of Mangere. A full primary, it caters for pupils in Years 1 to 8. Ninety per cent of the school population is Pasifika; nine per cent are Maori. In the foyer, Room 22’s beautiful, complex, multi-colour lino prints depict “us and our cultures”. Dozens of sports photos cover the walls up to the ceiling. Most are captioned “Auckland Champions” or “New Zealand Champions”. Around them, coloured A3 sheets bear handwritten messages in bold black: “Who will be our first Olympian? Could it be you?”

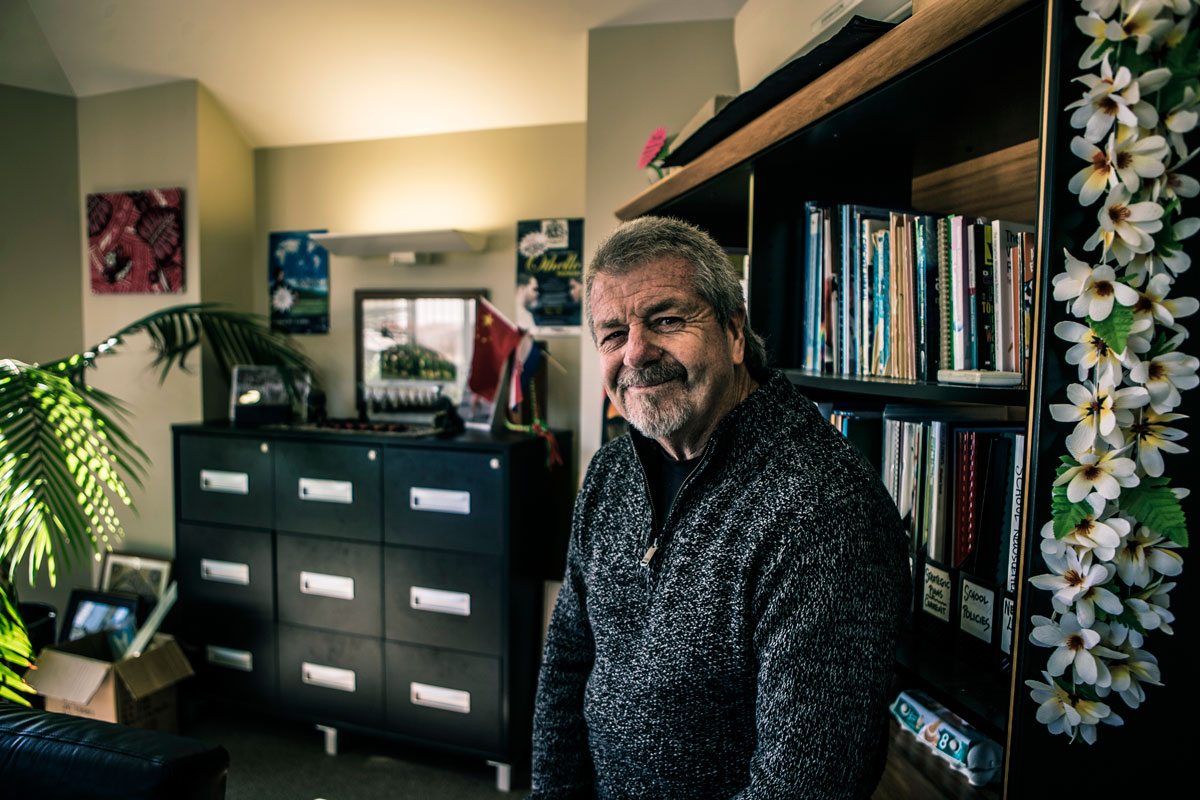

Keith Gayford, Viscount’s principal, wears his authority lightly. Casual in polo shirt and slacks, his haircut one step from a mullet, he offers a hearty handshake before bounding up the stairs for his first task of the day. Every morning, Gayford personally updates the staff whiteboard, noting events and recent sporting successes. The changing board encourages staff to gather and talk in a way that “isolating” emails can’t. Here the coloured A3 sheets bear messages for staff: “Shakespeare was in someone’s class when he was seven. Who is in your class right now?” and “One of the reasons adults should look like they are having fun is to give kids a reason to grow up!”

The Ministry of Education calls this “Viscount School”. The school’s signage, website and principal call it “Viscount Learning Community”. The difference is not simply semantic. Where the ministry gathers statistics, Gayford and his team gather people. In a school, authorities take charge. In a community, everyone takes responsibility. “Of course the kids greet people,” he says when I mention my reception. “That’s what you do when someone is visiting your home.”

At the heart of the community are Diana Tui and Meafou Tavui. Both are ex-students. Gayford says the pair are “gold-dust to me. They know every parent, every auntie and uncle. Meafou’s got all the student files in her head.” Meafou has spent more than half her life at the school. She tells me she and Diana are hugely grateful to work at Viscount. “Not just because of the work, but because of the staff, the families and the kids. We so appreciate the community.”

During the morning, they dispense information, smiles, advice and pears to all-comers. A small boy sits cross-legged beside a pot-plant, staring stoically at the wall. His Indian teacher asks Meafou to tell him he should get his morning tea and come back. She does, in rapid Samoan. The boy meanders off; she says, “Fa’atope!” and he breaks into a trot. “We give of our best to help them,” she says.

B.E.S.T. is this community’s motto. Standing for “Better Every Single Time”, it sets the expectation for continuous improvement at every level. Each year, each class, creates hearts, expressing its own values. “That’s not just twee semantics — kids put a lot of effort into them, and living up to them.” In Room 22, colourful Cellophane hearts dangle from the ceiling bearing messages: INTEGRITY, TRUSTING, MATURITY, POSITIVE ATTITUDE, STRIVE FOR SUCCESS.

At Viscount, they like to say there are only two rules: “I have an obligation to learn” and “I have an obligation to help others learn.” The expectation of individual excellence and collective responsibility creates a pervasive culture. “The kids understand what a learning community is, and they understand what their obligations are,” Gayford says.

Stopping someone from learning is “the worst crime you can commit at this school”. Even new entrants grab hold of the key concept. “One little girl, only here a couple of weeks,” Gayford remembers, “turns up in my office with two boys twice her size by the scruff of the neck and says, ‘They were stopping me from learning.’” The culture is so ingrained that when someone new arrives, the class will “turn them into a Viscount kid really quickly”.

Speed is important, because pupils come and go. Gayford flicks through the 2014 student lists: yellow highlights for students who have left, red underlines for students who have joined late. Just nine weeks into the school year, every class has yellow and red stripes. Gayford says people think he’s making it up when he quotes the numbers. Only 40 per cent of students move through as a cohort.

Viscount churns more than 200 students a year. “Most schools in New Zealand don’t have that many kids total. We turn that many over.” Accommodation is a big factor: local housing is mainly state houses, which aren’t permanent; the tight housing market and rising interest rates compound the problem. But Gayford won’t let environmental factors dictate outcomes or generate pity. “These people don’t need your sympathy,” he says, “they need your expertise and your energy.”

When Gayford arrived 20 years ago, Viscount “had been run down to nothing”. Buildings were regularly set on fire and burgled; the school had the biggest vandal damage bill in the country. Students expelled from everywhere else came to Viscount. There were no expectations around behaviour or achievement. Crimes were celebrated.

In one spectacular case, a 12-year-old student and his mate stole a bus, drove home to collect the family cat, gave a prostitute a lift to K’ Rd, and headed north. They were caught in Warkworth, trying to buy 50 cents worth of petrol. Gayford laughs. “That kid was a legend. His dad dined out on that story for years at the pub.” The story made the papers. All the stories coming out of Viscount, Gayford says, were bad ones.

Along with the negative press, Gayford inherited a school with “diabolical” reading statistics and no reading resources. He and his deputy principal spent huge sums on New Zealand’s best learn-to-read materials. After implementing these tools, they retested — and the results were “still diabolical!” Gayford refused to accept that Viscount students could not be fluent readers by age seven. The teachers were working hard, using similar programmes to other schools, “and still the kids were reading like crap”.

When challenged, the teachers listed dozens of potential contributing factors, mainly socio-economic, such as lack of pre-schooling and inadequate access to books. Gayford decided to test the next intake of five-year-olds to see how many factors applied. The result? “Ninety-eight per cent of the kids had 98 per cent of the things the teachers said they didn’t.”

There was only one conclusion: the teaching wasn’t leading to learning. Enter Rosemary Fenwick, a reading specialist who had worked for the London Education Authority. She guaranteed to improve the children’s reading results “off the planet” in six months. Gayford laughs. “An outrageous claim. It just doesn’t happen that way.”

Fenwick went to work training Year 1 teachers. New Zealand Council for Educational Research standardised running records were used to measure progress. Within a year, Gayford saw “this bubble of over-achievement coming through, pushing up the levels”.

In 2000, only 18 per cent of Year 3 students were fluent, age-appropriate readers at age seven. By 2009, 58 per cent were reading above their age level in Year 3. Between 2000 and 2004, as the rest of the school’s teachers received their training, the average reading age of Viscount’s Year 8 students (aged about 12) rose from 11.9 years to 13.2 years. Until 2009 (when National Standards were introduced), the average reading age for graduates peaked at 14.7 and never fell below 13.

In 2009, 300 of Viscount’s students were eligible for full ESOL funding — that is, they were learning to read in English as their second language. “Eighty per cent of our kids come to school not speaking English at home,” Gayford tells me. “That’s not deficit thinking; that’s just a fact. You can’t change the starting point. But you can change the finish point.”

Investing in people is the key. Ministry professional development programmes fall well short of Viscount’s needs. Gayford’s aim is “to teach teachers to teach differently, and give them the circumstances to do it in”. Class sizes are kept as small as the school can afford. Extra teachers, and subject specialists, are hired at the school’s expense to lift teacher numbers above the government allocation. Teachers use reading resources developed in-house, which Gayford describes as “second to none”.

Fenwick is still on staff, providing every new teacher at Viscount with a six-day, in-house programme on teaching reading, and an ongoing advisory service. Says Gayford: “Reading’s done the same way in every class throughout the school, Year 1 to Year 8. That’s important. The kids can run the programme. They teach relievers about it. They’re safe and secure. It works.”

The statistics bear out the assertion. Using the 2012 National Standards results for reading, by Year 7/8 (intermediate level), 66 per cent of Viscount’s students were reaching or exceeding the standard, with 41 per cent above. (As a comparison, two other local intermediate schools have just 27 per cent and 51 per cent of students achieving or exceeding, with only eight per cent and 20 per cent achieving above.)

The school’s Information Centre features in a National Library web video, “School Libraries: Excellence in Practice”. Kids of all sizes beam from the screen, waving books, enthusing about their favourite stories, describing the specialised help they get with projects. Director of learning Fran Mes explains that the seeming chaos of the environment is actually ordered to facilitate collaboration and inquiry.

Inquiry learning is central to Viscount’s philosophy. In the late 90s, Gayford “threw out the curriculum documents” in favour of a new model. In 2002, Viscount became a lead school in a government programme to teach other institutions about learning through inquiry.

People were surprised by the inclusion of a decile-one school, says Gayford, assuming the lead schools would all be decile 10. “After all,” he adds wryly, “that’s where all the good learning happens, isn’t it?”

The programme enhanced the school’s reputation, and proved a “fantastic exercise”. Every week, Viscount was entertaining teachers doing professional development. Panels of students learned to present to international groups about inquiry learning. Staff were questioned on why they did what they did, forcing them into constant re-evaluation of their teaching practice.

Judging the true impact of teaching, positive or negative, has always been difficult. “Teaching’s one of those professions where you can’t tell how successful you are until the people you’ve taught have lived their lives and died,” Gayford says. That’s why Viscount works hard to stay “significantly in touch, not just superficially”.

It’s important to track “how our students do in Year 9, Year 10, their first year in university, their first year in the Blues team, as a lawyer or a Shakespearean actor or whatever.”

It’s a big job, given that Viscount feeds to more than a dozen high schools. “Yes,” says Gayford, “but we honestly want to know that what we do is having an effect.”

Gayford’s office is plastered with photographs and newspaper clippings of former students. Taped to the wall next to his desk are three high-school reports, all bearing the same name. At Viscount, this boy was trouble. Hailing from a family of gang members and jailbirds, his behaviour was aggressive and anti-social. On one occasion, he was caught chasing fellow students with a set of knuckledusters. Gayford confiscated the dusters and was called extremely colourful names. “I nearly threw him out so many times,” Gayford remembers. However, the community persevered, recognising potential. Their investment paid off. By his final year at Viscount, the kid had decided “he didn’t want to be a dickhead like the other guys in the streets”.

Now in his fourth year at a prestigious boys school, the student is a prefect, a school leader and a member of the 1st XV. The reports, Gayford says, “track the progress from one life… to an unknown life. When he was 10, I could have told you what his life was going to be. Easy. Jail, by now.”

Last year, Gayford returned the knuckledusters to the student. “He laughed and said, ‘Yeah, that was me, wasn’t it?’ as if he were talking about somebody else.

“Those are the ones,” Gayford says in satisfaction, “that keep you getting up every morning.” Knowing you can make a difference is the difference. “We helped him enormously to get there — emotionally, physically, and financially — and still do.”

The boy returns several times a year and talks to current students about taking responsibility. If he needs something, the kids do a fundraiser for him.

Successful graduates are part of a positive feedback loop for all concerned. “It’s really important to have their faces and their achievements in front of these kids — and their teachers,” Gayford says. One graduate, recently selected to represent New Zealand at the Commonwealth Games, works at Viscount as a sports aide, teaching discus in the school throwing circle where she developed her skills.

A favourite photo of Gayford’s features two ex-students, one in the Japanese national rugby team, the other an All Black: “two Viscount boys, at the top of world sport, playing against each other”. Then there’s the group of graduates who formed the Black Friars Theatre Company.

In a TVNZ documentary, the Black Friars wax lyrical about their primary education. One says, “The best thing about Viscount is having a principal who understands the needs of Polynesians — what we excel in.”

Working from student strengths builds confidence. Given students’ varied language backgrounds, reading and writing may be challenging at first. The school capitalises on students’ non-linguistic abilities in areas such as music, drama, art — and, of course, sport. Tangible successes help kids to believe they can achieve.

Gayford has no qualms about competition. “Sports is for winning; it’s not for taking part,” he says bluntly. “Life is competitive. If you don’t know how to compete, you crash and burn and end up working in McDonald’s.” Sport is straightforward: there are winners and losers. Gayford wants his kids to be winners — and not just within the traditional spheres of rugby and netball. Hence the investment in a proper throwing circle, which has helped produce athletics champions for over a decade.

Cricket — “such a white, middle-class game” — is another sport in which Viscount has had spectacular and unlikely success. In 1999, Gayford received a flyer about the Milo New Zealand cricket championships. He entered a team — despite not having a team. The newly employed phys-ed instructor was confronted with a bunch of complete newbies heading into a national competition.

That year, the girls’ team won the Auckland championship; the next year, they became New Zealand champs. They’ve been champs or runners-up every year since. “Boy, the lessons we learnt,” Gayford says. “To play cricket well, you’ve got to work hard for a long period of time. You can’t just do it with natural ability.”

This is Gayford’s 20th year at Viscount; his senior leaders have been with him for more than a decade. The team consists of his deputy principal, Barbara Woods, who joined the community in 1997, and three “directors of learning”. The nebulous title encourages people to ask about the job, challenging preconceptions about leadership roles.

Gayford says all of his leaders were “incredibly high-calibre teachers originally”. Any of them could be a principal elsewhere by now. Instead, they’ve stayed at Viscount. Why? “Well, I don’t offer them more money. So it’s not money.” Gayford believes it’s the satisfaction of doing what they’re good at, and having a measurable impact on learning. He also takes pains to protect them from “compliance crap and ministry bullshit”, allowing them to focus on teachers and kids. He says with a grin, “I think that’s pretty key to keeping them enthused and motivated.”

Additionally, jobs are flexible; staff have input into their roles. Extra money goes into professional development, not leaders’ pay packets. Gayford gets staff to places “where they can match wits with the best thinkers in the world”. Group leadership trips have included “windswept and interesting places” from Sweden to America. The team has gone the extra miles together “to test ourselves, to test our thinking”.

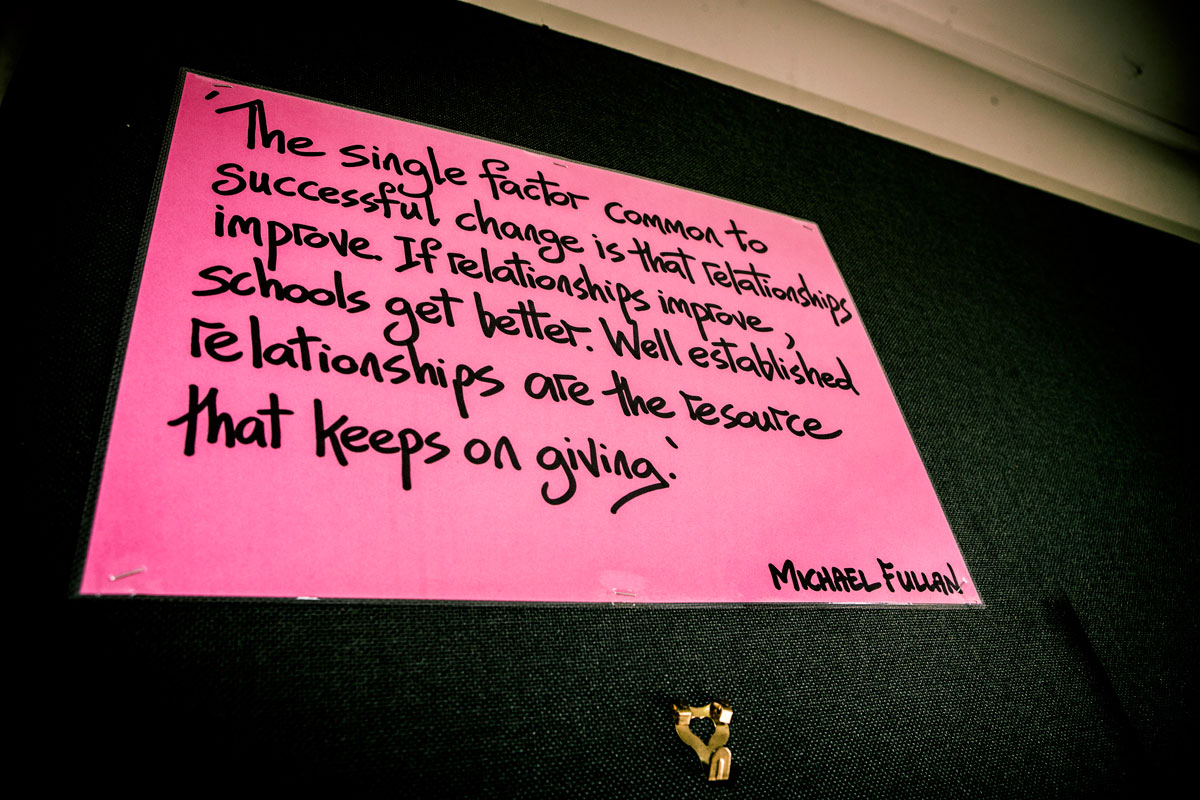

The result of this investment is remarkable staff retention. “We’ve got miles on the clock together. That’s the main reason the school works.” He believes many schools struggle because they can’t hold onto critical people long enough to build trust. Trust isn’t the result of policies, or saying, Let’s go on a leadership weekend to Waiheke. “That’s bullshit. Trust takes time.”

He is scathing about leaders who leave struggling schools after only a few years. “I loathe them. If you’re really committed to communities like this, you’ve got to stay for a decent time, to see if what you did worked.”

What does Gayford think of additional pay for “leadership principals” to instruct others? “A curious idea, isn’t it? It’s very contrived.” He has no time for leaders who are in it for the money — the ones most likely to put their hands up for the job.

“Who’s going to collaborate with them?” Gayford asks. “It runs contrary to the whole ethos behind good leaders in schools.”

Impressing the ministry is not one of Gayford’s primary concerns. “In terms of policy and how it affects us, you have to take a longer view — otherwise you’d go crazy. Trying to react to every government that comes in and comes up with another harebrained scheme, you’ll miss the point.”

The point is educating the 700 kids who turn up to school each morning, regardless of who is in the ministry. He feels that the independence of Tomorrow’s Schools, which “gave good principals, good leaders, the chance to do what they knew was right anyway”, is being eroded. He is determined to continue to work from heartfelt belief regardless. “I’m not doing this to look famous. I’m doing it so I can look parents, teachers and the board in the eye and say, ‘We did our best for these kids.’”

His focus is firmly on building his community’s future. The diggers have just broken ground on a new building project. “Come back in a year and I’ll show you what a real 21st-century learning environment looks like. The old-style classroom is about order, not about learning. This will be totally different.”

First published in Metro, June 2014. Photos: Vicki Leopold