Mar 30, 2018 Politics

McShane was an outspoken commentator who made an outsized contribution to New Zealand public policy. We both reckoned it was time Auckland shook off an ungrateful New Zealand and became independent.

The old iconic cover of the New Yorker, depicting Manhattan in the foreground and the desert stretching endlessly behind to the horizon, reflected our image of Auckland and the rest of New Zealand. A booming metropolis of energy and success, while green fields full of cows and sheep rolled on to Wellington.

McShane wanted to name the new city-state “Akarana”, the Maori transliteration of Auckland. What remained of the old country, all that quaint rolling pasture and those few little cities, would be “Zealandia”. Akarana would be as successful, progressive and visionary as Singapore, investing as that small nation does in the only “key natural resource” it possesses — “the one between its people’s ears”.

This was so important to McShane that he shaped the borders of Akarana to exclude natural resources from its territory. Zealandia could keep all the natural wealth. The very existence of such resources “makes nations too comfortable”, he reckoned, “overconfident of their ongoing economic wellbeing”. He drew on his knowledge of post-war economies to argue his point.

“When a population knows it has nothing else going for it,” he contended, “it educates its people and ensures that they are given the environment to create real wealth rather than depend on digging it out of the ground.” McShane wanted to consciously build Akarana on that principle.

From that natural dividing line of the Bombay Hills, the border of Akarana would wrap around the Hunua Ranges, securing the city’s water supply — the reservoirs built by Auckland ratepayers — and take in the Hauraki Gulf, the thousand square miles of South Pacific that is the natural adjunct to the “City of Sails”.

Aucklanders had to disguise their origins when drinking in country pubs. We were called “jafas”. It’s interesting that there are no pejorative names for the people of other regions. Perhaps, if we could be bothered (and we probably can’t), we might call the inhabitants of Zealandia “Zealots”, after their religiously held belief that they’d be better off without us.

And this was really McShane’s case for an Auckland city-state. A Stuff article from 2016, outlining how vital Auckland is to New Zealand and how few Aucklanders turn out to vote in local body elections, posed the question, “Is Auckland too important to be left to Aucklanders?” But that’s beside the point, as the rest of New Zealand refuses to recognise the city’s importance.

Auckland and Aucklanders are too often dismissed, distrusted and disliked by the rest of the country. The “politically worthy”, in McShane’s term, are to be found in the rest of New Zealand, usually by definition, especially “in some remote rural region”. His assertion that Aucklanders were “politically unworthy” was proved as tellingly as it could have been when the Cabinet post of Minister for Auckland, recommended by the royal commission that created the Super City, was not accepted by Wellington.

McShane reckoned the only way an Auckland held unworthy of inclusion by the rest of the country could “secure our ongoing wellbeing” was to secede. I think he’s right.

They seem convinced, below the Bombay Hills, that we spend our time looking down at them, thinking ourselves superior. It’s a reflection of their thoughts, of course, not ours. The truth is we hardly think of them at all. We consider ourselves New Zealanders who come from Auckland, no better or worse than anyone else. They think of us as another people, from an arrogant alien land that takes from them but gives nothing back.

“Auckland is a sick city,” went another riposte that was not to the argument, or even to the man, but to the place. “Not only does it lack any soul it is also a complete cultiral [sic] desert full of awful wannabe upwardly mobile people whose only redeeming feature is they dont [sic] live in the rest of nz. Surely the best planning option would be to nuke the whole place?”

Well, at least they were open-minded enough to offer a question mark over the nuclear option.

There is a startling demographic trend beneath this dislike for Auckland, outlined in the comprehensive A New Zealand Urban Population Database produced by Motu Economic and Public Policy Research. Since 1926, and probably before, growth rates in every region but Auckland limp along the bottom of the graph, struggling to lift from the bottom axis. Auckland, meanwhile, is always ahead of the curve, and breaks away dramatically after 1945 to climb steeper with each decade.

I suspect that curve correlates well with the growth of vocal hostility towards Auckland. With density of population comes a concentration of everything else, and opportunity in almost every field. Simon Wilson argued in Metro in 2009 that Auckland was more of a cultural capital than Wellington (“Auckland rules OK! How Wellington’s losing the culture wars,” ran the coverline). So much for the “cultiral” desert.

Add to that Auckland’s superb “green and blue arcadian spaces”, in McShane’s romantic phrase, and a climate more temperate than anywhere south of the Bombays. Auckland has held third place in the Mercer Quality of Living Index for six years (and is the sixth friendliest city in the world, according to a 2017 Condé Nast readers’ survey).

White-sand beaches along Tamaki Drive to Kohimarama and up the east coast bays; the welcoming sweep of the Hauraki Gulf; the quiet vineyards of Waiheke within sight of the CBD skyscrapers; the wild nature of the Waitakeres that lead down to the black-sand surf beaches out west — all this is within a handful of miles from the urban centre of a truly international city, the only one in the country.

This is, I’m sure, another reason for New Zealand’s hostility towards Auckland. The city threatens because it is so attractive, especially to the young. The 2013 Census showed that close to 10,000 New Zealanders move from the regions to Auckland each year, with the city acquiring net gains in the 15-29 age group. Youth seeks opportunity and Auckland offers it.

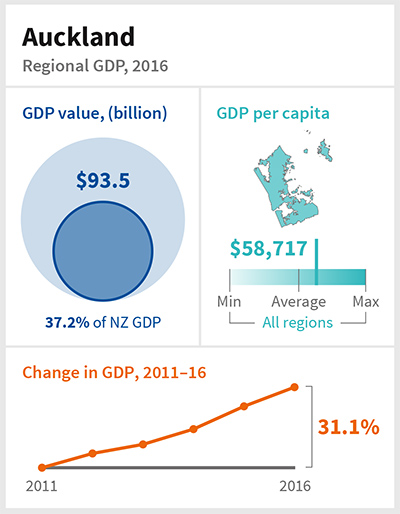

Its population and economy are simply growing faster than the rest of New Zealand’s, and indications are that growth is accelerating. Since 2011, according to the Auckland Growth Monitor published by Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development (Ateed), “Auckland’s GDP has grown at an average annual rate of 3.4 per cent, and between 2015 and 2016 grew by 3.9 per cent”. In the rest of New Zealand GDP grew at a steady 2.5 per cent, rising only to 2.7 per cent in 2015 and 2016.

Auckland is forecast to have two million residents by 2033, and by 2045 it will be home to 40 per cent of the national population. We are set apart, and probably have been since Hobson anchored in the Waitemata in 1840. It just took a century to become evident.

Auckland occupies less than two per cent of New Zealand’s landmass, but 34 per cent of the population already live here. The region takes half of all migrants to New Zealand, and has accommodated a population the size of Wellington in just the past decade, 45,000 people in 2016 alone. Some 39 per cent of Aucklanders were born overseas (foreign-born citizens make up only 18 per cent of the rest of New Zealand), making the city the fourth most ethnically diverse in the world. Aucklanders are also in general slightly younger, better educated and higher paid than other New Zealanders.

Along with an increasing percentage of the national population, Auckland has a greater proportion of working-age adults than the national average.

Over a third of New Zealand businesses, and two-thirds of the nation’s top 200 technology firms, are based in Auckland. More than 100 multinational companies have their Asia-Pacific headquarters here. The region already generates 37 per cent of the nation’s gross domestic product. The trends outlined above would indicate this is likely to increase.

So the Zealots have a point: Auckland in many ways is a different country. Other regions are, meanwhile, “struggling with ageing populations and drifting economies”, as economist Peter Nunns wrote in a Greater Auckland blog post in 2015. He did some research to see if their further claim was true. “If the city’s prospering while small towns decline,” he posited, “isn’t it because the government is spending too much money trying to pump growth into Auckland and too little elsewhere? In short, is Auckland costing New Zealand too much?”

So the Zealots have a point: Auckland in many ways is a different country. Other regions are, meanwhile, “struggling with ageing populations and drifting economies”, as economist Peter Nunns wrote in a Greater Auckland blog post in 2015. He did some research to see if their further claim was true. “If the city’s prospering while small towns decline,” he posited, “isn’t it because the government is spending too much money trying to pump growth into Auckland and too little elsewhere? In short, is Auckland costing New Zealand too much?”

“The answer,” Nunns discovered, “is no.” Auckland receives around 31 per cent of Government expenditure, slightly less than its share of the population. Far from being “the rapacious parasite that some people make it out to be”, Nunns concluded, Auckland isn’t “sucking small towns dry of their tax dollars. If anything, it’s the opposite: taxes paid in Auckland fund pensions for small town residents.”

This difference and divergence is only going to increase. Auckland will rapidly grow in population and economic power while the rest of New Zealand, in relative terms, will meander on, always a comparative backwater. This is a problem for the rest of the country. The demographic and economic imbalance, it seems unarguable, will attract their young and the talented.

From Auckland’s perspective, the nation, already taking more from us than we get from them, will take more and more in the future. At the same time, we will become more despised and distrusted, and Wellington bureaucracy will increasingly seek to constrain us even though we hold all the real power.

Never mind how the Zealots view Auckland. It’s more important that Auckland today sees itself as monolithic and bound by traffic and council, both of which seem to spend too much time getting nowhere fast. It needs to free itself and start seriously becoming a global player.

As McShane recognised, there is only one direction it can follow. In shaping his vision of Akarana by excluding natural resources, McShane was making a wider point about New Zealand that is increasingly evident.

The Auckland economy, dominated by manufacturing, education, and service industries, with a burgeoning tech sector and an ongoing building boom, is the only buttress New Zealand has against fluctuating agricultural fortunes. It needs to be recognised, too, that there are challenges to our traditional agricultural sector from both biotechnology advancements and the environmental lobby. The latter objects to it on everything from basic principle to the size-16 carbon footprints that trek our “clean green” goods to foreign markets. Witness prominent film director (and New Zealand resident) James Cameron’s recent opinion piece in the Guardian. “We simply need to eat less meat and dairy,” he wrote, “if we’re to reach our climate goals.” Farming once gave New Zealand one of the highest living standards in the world. That time is over.

Auckland must be a city-state that, in McShane’s words, “educates its people and ensures that they are given the environment to create real wealth”. The creation of high added-value industry at the cutting edge of high technology is essential.

The city is already deliberately moving towards an innovation economy, and its tech sector has grown 26 per cent since 2012. Over a quarter of its workforce is employed in the technology sector, which accounts for half of New Zealand’s total technology workforce.

Creativity will be celebrated in the Auckland city-state, and brains and genius and aspirations will be grouped together, as they are now at a small scale at The Grid in Wynyard Quarter’s Innovation Precinct. The entire city-state will become a start-up ecosystem of universities, research organisations, large companies and venture capital, all feeding off each other to grow. Money and finance will be core to the system, the dollar applauded and not devalued.

There are important other aspects to that “environment to create real wealth”, though. One of them is freedom.

It was freedom that was the hallmark of classical city-states such as Athens and later Venice. Freedom attracted the best and brightest to their territory, fuelled their progress in both art and science, and drove their prosperity. The Auckland city-state will enshrine and ensure the freedom of the individual, of information, of expression, encouraging the flow and exchange of ideas.

Another aspect of the “environment to create real wealth” is a liveable city, and this isn’t a subjective quality. There are metrics that can be measured, from air and water quality to how quick, convenient and costly it is for citizens to get around, especially by public transport. The governance of the city-state will be charged with maximising such measured positive outcomes of human, economic and environmental wellbeing.

How many research papers are published? How many patents granted? How many businesses started? Are homelessness and poverty being reduced? Is higher education becoming more accessible? Is the level of higher education increasing, particularly in vital areas of science and engineering?

Fiorello La Guardia, the great New York mayor who cleaned up and revitalised that city, once said, “There is no Republican or Democratic way of fixing a sewer.” Local government is practical, not ideological. This model provides a practical, measurable, transparent approach to good governance.

The existing Auckland Council system, which for over seven years has proved not up to the game, must be abolished to make this happen. The office of mayor, with its medieval title and chains, will be replaced by a governor elected at large.

Singapore, when it was dominated by the rubber barons of Malaysia, once rotted in poverty, typhoid and malaria. Lee Kuan Yew once told me that when he walked to school as a child he saw bodies in the gutters. Singaporeans were illiterate, starving and dying of malnutrition. The creation of the Singaporean city-state was a determined and hard-nosed vision of leadership. Although Auckland faces nothing like the same transition, it needs the same.

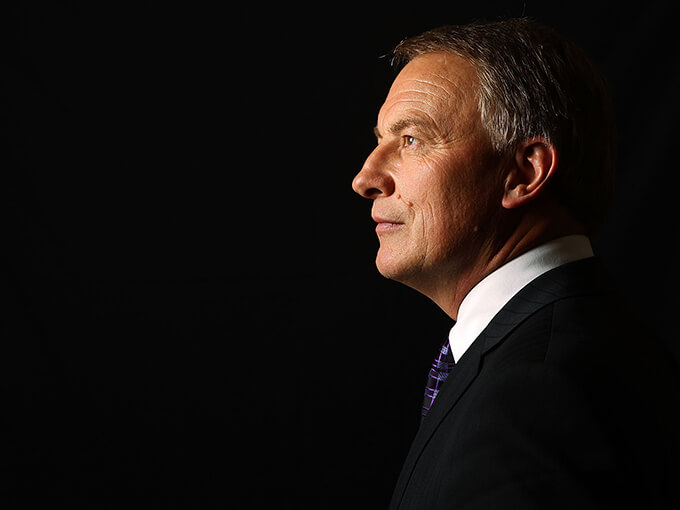

The office of Auckland governor doesn’t demand a person of vision — the vision will be enshrined in what the governor is constitutionally charged with accomplishing. Rather, it will take someone with the determination and powers to push the vision into reality. In my opinion, Mayor Phil Goff fits the role, but his experience in Wellington and the international arena is not supported by like-minded councillors. Their second-rate behaviour frustrates him, I’m sure.

Auckland has suffered from this for too long, and the Super City was meant to solve it. The Auckland city-state will replace the council with the London governance model, which the late Mark Ford, leading architect of the Super City, always intended. The Royal Commission on Auckland Governance neatly side-stepped his recommendation. It was the wrong decision.

In this model an empowered mayor — or governor, in the case of the city-state — is tasked with promoting economic development and wealth creation, social development, and the improvement of the environment. The office has strong strategic powers, though not without constraint. Scrutiny is provided by a small assembly elected at large. Accountability is achieved through conducting business in public, publicising strategies, annual reports, and being regularly subject to direct questioning by the public.

This is how you get things done.

And what of that liveable Auckland? A pink cycleway is all very well, a vibrant brushstroke across the cityscape, but it signifies nothing. The city needs a carless CBD, perhaps with an underground Personal Rapid Transit system, and high-speed rail-links to the north and south and a second harbour crossing via a tunnel under the Waitemata.

And what of that liveable Auckland? A pink cycleway is all very well, a vibrant brushstroke across the cityscape, but it signifies nothing. The city needs a carless CBD, perhaps with an underground Personal Rapid Transit system, and high-speed rail-links to the north and south and a second harbour crossing via a tunnel under the Waitemata.

We have the talent to do all of this and much more. Council planners and designers are at the top of their game. They understand global cities. Auckland Conversations, “free public events offering ideas, inspiration and action for world-class cities”, the brainchild of council design champion Ludo Campbell-Reid, brings world experts on governance, transport and design to Auckland every month. The desire for knowledge fills the Aotea Centre.

Meanwhile, what might be considered the first major infrastructure of the Auckland city-state has just been funded. It’s intriguing how it fits with McShane’s vision, establishing a fundamental economic connection between Auckland and Northland.

Aucklanders have had enough of rows of cars on downtown wharves, and few of them support further reclamation to push big, ugly wharves deeper into their beloved Waitemata to dock more big, ugly ships.

In November 2017, Ports of Auckland revealed its 30-year draft plan for its prime 77 hectares of land next to the central city, which it occupies rent-free. “We are listening,” chief executive Tony Gibson told the Herald, referring to past vocal public criticism of wharf expansion. “That’s the new us.” Yet the new plan would extend Bledisloe Wharf 13 metres further into the Waitemata.

Ports of Auckland has a mandate to fulfil and is trying to do it, but Aucklanders by and large object to a bigger cargo-wharf footprint. Ports of Auckland can’t win this game, so the rules must be changed.

We obviously need a port, but the city has outgrown the central-city wharves, just as shipping demand is outgrowing the port’s capacity. Whangarei’s Northport and a rejuvenated North Auckland Line are the obvious answer — in fact, the only answer.

New Zealand First leader Winston Peters agrees. A month before the 2017 election, he announced a policy to relocate the Port of Auckland to Marsden Pt by 2027. “Aucklanders want their harbour back,” he said, “while Northlanders want the jobs and opportunity that would come from Northport’s transformation.”

Northport should become the cargo port of the Auckland city-state. The double rail link, which would cross West Auckland on land already set aside for it, would speed containers to and from yet-to-be built inland ports at Onehunga and Manukau. Ports of Auckland would manage the transhipment of cargo from these major “dry ports”.

Right now, the ports of Auckland, Whangarei and Tauranga, locked in competition, are being squeezed mercilessly by the freight-shipping-line monoliths. This must be stopped, but the previous Government demonstrated an outrageous lack of energy to do anything about it. Peters must call for an urgent review, in my opinion. It will soon demolish the rumour that costs will go up 40 per cent if goods come through Whangarei.

Sweeping vision is all well and good, but it takes money to build it into substance. This is exactly why the moment is right to create the Auckland city-state. The immense Chinese investment initiative “One Belt and One Road” can give Auckland its infrastructure future. The Belt and Road, as it’s known, is a reinvention of the ancient Silk Road and looks to cement connectivity and cooperation between nations and with China. The anticipated investment on offer is estimated at anywhere from US$4 trillion to US$8 trillion.

Auckland can attract its share of this massive investment via the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road initiative, an offshoot of Belt and Road that delves into the Pacific, particularly with strong concepts for major infrastructure programmes. The opportunity is unprecedented, historically fleeting and will never be repeated.

Belt and Road investments in Auckland can be paid back over a 150-year period. Such infrastructure projects will add strength to a high-tech, high-added-value economy, and will in fact be the framework it rests upon. And remember, 400,000 Chinese visitors spent NZ$1.5 billion in New Zealand last year.

McShane’s vision of Akarana went so far as to treat New Zealanders from outside Auckland as foreigners. Together we thought of the Auckland Harbour Bridge toll booths. That was to pay for the bridge, so why not charge the rest of New Zealand to pay for Auckland when they cross city limits?

It would have been intrusive and difficult then. With the electronic toll technology we have now, we could easily stretch a virtual border around Auckland, with traffic flowing as normal into the city under electronic eyes.

Likewise, McShane and I dreamed of an Auckland passport, and of airline tickets that would tax people five dollars to enter the city from other regions.

Why should Aucklanders suffer a fuel tax when their city dominates the New Zealand economy, already loses money to the rest of the country, and keeps the major infrastructure that supports the nation?

McShane was, as usual, ahead of the curve when he envisioned Akarana. Today, there is increasing talk of the rebirth of the city-state, because that is where power is centred in the modern world. “Cities have become the organising unit around which the world economy is currently structured,” Ateed executive Patrick McVeigh told Stuff in 2016.

In New Zealand, this structure is entirely focused on Auckland. “The impact and consequences of what happens in Auckland,” McVeigh made clear, “are probably felt more than they might be if you were in a network of five or six cities of major size.”

These cities are not only the powerhouse of economies, they often possess significant demographic, economic and cultural differences from the nations of which they are a part.

Perhaps only the UK shows as great an imbalance between their major city and the rest of the nation as New Zealand. And in London, there is a growing movement advocating “Londependence”.

One of the arguments is that it would benefit the rest of the UK. London, like Auckland, impairs the rest of the country by drawing the majority of talent, resources and investment. A London city-state offers what may be the only chance for the rest of Britain to become geographically and economically balanced. The same is true for an Auckland city-state and New Zealand. Support for the Londependence idea among Londoners has doubled in recent years, to 11 per cent. Some polls have put it at closer to 20 per cent. There is no reason a similar “Aucklandependence” movement wouldn’t attract support here.

McShane’s vision of Akarana inspired me to create an Eco City when I became Mayor of Waitakere in 1992. It was really a gentler, small-scale version of his utopia in the South Seas. I suffered the derision of Wellington, of the politicians of the day. I was creating something unique and visionary and slightly futuristic and they didn’t understand it, or didn’t want to, and they didn’t think it would work. I proved them wrong.

You can cut the pathways to real change, or you can stumble through the overgrowth with your head down. For seven years I’ve waited for the lamentably named Super City to take off. Instead, it’s been a rocket stuck on the launch pad, its economic engine roaring. There has been movement, because Auckland has finally been able to organise and advocate with one voice. But this is nothing compared to where Auckland could go.

Wellington will dismiss the idea of the Auckland city-state, too, of course. Its bureaucrats speak a different language, and their very existence is wrapped in keeping Auckland on a leash with its head down. Visit the Koru Lounge at Auckland Airport any Monday to see the delegations heading south to make nice or plead with a begging bowl.

Should the city-state idea not fly, the eventual return of the capital to Auckland is inevitable (which will only make New Zealand an Auckland city-state writ large). It is a matter of when, not if, Wellington will be devastated by a major earthquake. Auckland must prepare to accommodate the New Zealand Government when this tragedy occurs — and it’s a major failure of national strategic planning that it isn’t ready now.

Perhaps it should be remembered that Auckland was founded by the Crown, which was solicited by Ngati Whatua to “settle in their midst”. It was Wellington that was founded, on a completely unsuitable site, by the unscrupulous capitalists of the New Zealand Company — itself perhaps the worst thing that has ever happened to this country.

I expect most New Zealanders think an Auckland city-state will never exist. In a way, though, it already does. Auckland needs to live up to it, and New Zealand needs to accept it. If not, Zealandia will be left behind, adrift on those rolling green fields over the ridgeline of the Bombay Hills.