Jan 13, 2016 Politics

It is 10 years since Peter Brown’s Death with Dignity Bill was narrowly defeated in Parliament. In September, another member’s bill to legalise voluntary euthanasia was suddenly withdrawn. Graham Adams asks why the topic is such a political hot potato when public opinion polls repeatedly find a strong majority in favour.

This article was first published in the January 2014 issue of North & South magazine.

READ MORE: Lecretia Seales: the backlash begins

A decade after his Death with Dignity Bill was defeated in Parliament, former NZ First MP Peter Brown still sounds mystified by how the vote went against him.

Right up to the debate on his member’s bill in July 2003, “we had the numbers to get it across the line by two or three,” he tells me on the phone from Tauranga.

But, on the night, “One guy who’d promised to support the bill didn’t turn up. And one woman [MP] who had promised support changed her mind.” He thinks someone with influence in her electorate had leaned on her.

Certainly, Brown says, if the parliamentary vote had reflected opinion polls – which were running above 60 per cent in favour “even in 2003” – his bill should have got enough votes to at least send it to a select committee for public discussion. But it was defeated 60-58.

The past 10 years haven’t dimmed Brown’s passion for the cause, however. “It is a long time since my involvement in the voluntary euthanasia debate,” he says, “but this is still an issue where I strongly believe people are entitled to have their chance to express their view.”

Fat chance, you might think.

It’s one of the great mysteries of a modern democracy – a proposal that a majority of the public repeatedly approves in opinion polls finds no major political party will present it as official policy. And when a member’s bill to legalise it is lodged, its sponsor withdraws it before it can be drawn from the ballot because she doesn’t want it to become a “political football” in an election year.

Labour list MP Maryan Street lodged her member’s End of Life Choice Bill in July 2012 then withdrew it in September 2013 – even though it is a topic she feels very strongly about. It was widely speculated that senior party members had pressed her to drop it, but Street maintains it was entirely her decision. She says she intends to re-present the bill after the next election, and withdrawing it was purely for pragmatic reasons, not least because she didn’t want it “tainted by election-year dynamics” after she had “bent over backwards to make sure it wasn’t seen as a partisan measure”.

“Conscience issues – such as voluntary euthanasia, alcohol, abortion or prostitution – are very exposing for MPs,” she says. “Opposition to these things can be very vociferous and polarising, if people want to make it so.

“Suddenly, MPs can’t hide behind a manifesto. They have to make up their own minds and they usually don’t have the cover of a party position. They have to have the courage to nail their colours to the mast, or not.

“In election year, that is a riskier activity than in a non-election year.”

Yet should it be seen as so risky when opinion polls over two decades have shown that a clear majority of New Zealanders want the right to choose assistance to die if they are terminally ill?

In 1995, a One Network News-Colmar Brunton poll found 62 per cent of participants approved of voluntary euthanasia, with 27 per cent opposed and 10 per cent undecided.

In 2003, a Massey University survey showed 73 per cent of respondents wanted assisted suicide to be made legal if it was performed by a doctor (support dropped to 49 per cent if performed by others); a Voluntary Euthanasia Society survey in 2008 found 71 per cent backed a similar proposal.

Street cited to North & South the results of a 2012 Horizon Research poll which showed “a huge majority” in favour of her bill, with 62.9 per cent approving it and just 12.3 per cent opposed.

In October this year, National’s Phil Heatley – an avowed moral conservative – found to his surprise that 66 per cent of 977 respondents he polled in his electorate of Whangarei favoured some form of assisted suicide.

What’s more, the courts – reflecting public sentiment – often adopt a lenient position when sentencing those who help hasten the deaths of loved ones who are dying. In a widely reported case in late 2011, Sean Davison, a South Africa-based microbiologist, was sentenced to five months’ home detention in Dunedin after he pleaded guilty to a charge of “inciting and procuring” the attempted suicide of his 85-year-old mother, Patricia, in 2006. (He gave her crushed morphine tablets in a glass of water, at her request.)

In September 2012, Evans Mott was discharged without conviction in the High Court at Auckland after he assisted the suicide of his wife, Rosie , who had advanced multiple sclerosis, which meant she could not feed herself, was incontinent and had trouble walking. She had made a video that was presented to the court, in which she explained her decision to die.

To prove her husband was not present when she died, she asked him to go out and buy something from a shop.

As these and other court rulings show, attitudes to voluntary euthanasia are changing – Street says the “conversation has moved on a lot” in the past 10 years – but still no major political party has been willing to make it official campaign policy. Or even to propose its own bill when in government and allow its members, and those of other parties, a conscience vote, which is how National dealt this year with the question of giving SkyCity more pokie machines in exchange for building a convention centre in Auckland.

Peter Brown agrees such an approach would be a good way of presenting voluntary euthanasia for debate in Parliament. Also, he says, it could be subject to a binding referendum as a further check to make sure what Parliament decided was, indeed, what the public wanted.

When John Key was asked his opinion in October – after a coroner had commented at an inquest into an elderly woman’s suicide that voluntary euthanasia was a topic Parliament would have to address again – he said: “It’s hard to believe the government would put it on the agenda any time soon. Fundamentally, the government has to be confident it’s got the numbers, and I couldn’t be at all confident we’ve got the numbers. There would be quite a considerable portion of the National caucus that would vote against that. It is something best managed through that member’s process.”

(In the case referred to by the coroner, an 85-year-old widow in Lower Hutt had waited for her family to leave from a visit then used a homemade device to kill herself in what was described as “euthanasia by suffocation”. On the stuff.co.nz news website, a poll alongside the story drew 4269 votes, with two-thirds favouring the legalisation of euthanasia.)

The reluctance of our political leaders to deal with voluntary euthanasia as party policy – at least in terms of pledging a national discussion and referendum – is particularly hard to understand given we are a nation known for our pragmatism rather than our religious fervour.

Contrast a deeply Catholic nation such as France, where President François Hollande made publicly discussing the issue of voluntary euthanasia a campaign pledge in 2012, and said he would introduce a bill to legalise it. This despite a proposal to legalise assisted suicide having been defeated in the French Parliament in 2011.

And France, you might remember, saw street protests when same-sex marriage – another of Hollande’s campaign pledges – was voted into law this year.

Despite its long Catholic history, however, France also has a tradition of personal liberty and secularism, in which church and state are clearly separated. And, obviously, French politicians are a lot braver than ours.

In New Zealand, our parliamentarians have preferred to leave the question of voluntary euthanasia to the lottery of a member’s bill, which means any bill might not be picked to go before Parliament for weeks, months, years – or never at all.

Brown says that although he was reluctant to continue pursuing the issue after his bill’s defeat, he was persuaded by the many people contacting him in support to re-present it in 2004. But when he retired from politics five years later, his bill still hadn’t been drawn from the ballot.

After its defeat in 2003, he had discussed with Helen Clark the possibility of presenting it as a government measure. She’d voted for Brown’s proposal, but told him a member’s bill was still the best means of addressing the issue.

Why our most prominent politicians won’t front the issue seems even stranger when the leaders of our two biggest parties voted for Brown’s 2003 bill to proceed to a select committee. And John Key not only voted in favour, in August last year he told Newstalk ZB he “broadly supported” the principle of voluntary euthanasia and would consider it himself if he were terminally ill.

Labour’s leader David Cunliffe also voted in 2003 for it to proceed to a select committee, but when I emailed him in October to ask what he thought about voluntary euthanasia personally, he replied coyly: “I have a clear personal view on this issue. However, at this time, given my new responsibilities, I am refraining from stating it so as not to unduly influence any future conscience process that might arise.”

Green Party co-leader Russel Norman wasn’t an MP in 2003, but he told 3 News in 2012 that he’d be voting for Maryan Street’s End of Life Choice Bill, adding: “I think it should go to select committee. I think we should have the debate about it as a country.”

But when I asked him in October if that was still his stance on the bill and whether he would “vote for it when it is reintroduced [by Maryan Street]”, he didn’t answer but passed the email on to Kevin Hague, who describes himself as the party’s spokesman on “healthcare issues, including end-of-life ones”.

Hague said he was “disappointed that Maryan has withdrawn her bill, but understand her reasons for doing so”.

The Greens “have a process under way to develop policy [on assisted dying], but it has been moving slowly and is now very unlikely to be finalised before the next election”.

Reviewing attempts to legalise voluntary euthanasia over the past 20 years, you could be excused for thinking most politicians don’t really want the public to be given the chance to discuss the topic at all.

In 1995, then-National MP Michael Laws presented his Death with Dignity Bill, jointly drafted by former MP Cam Campion, who was dying of cancer. It was proposed that the bill would become law only after a binding national referendum, to be held with the general election in 1996.

The purpose of the debate was to decide whether the bill should be introduced to the House and then discussed at select committee hearings. That proposal was defeated 61-29, with many abstentions.

When Parliament discussed the matter next in 2003, Brown emphasised he was “not asking anybody here in the House to make the final decision”.

“This bill – should it pass all stages – will go before the public of New Zealand, so that the public can make the decision by means of a binding referendum.”

Parliament, after a short debate, again decided against allowing it to progress further.

Who exactly, you may wonder, is so keen to make sure the public never even gets the chance to officially discuss that most fundamental of human questions: should I live or should I die?

In 2000, Labour MP Chris Carter blamed a “vociferous moral minority” wielding undue influence. Brown says the principal opponents of his bill were the Catholic Church and the New Zealand Medical Association, which publicly announced its opposition in the run-up to the parliamentary debate.

Nothing much has changed in 10 years. In September, Ken Orr, spokesman for Catholic advocacy group Right to Life New Zealand, wrote on its website that the organisation had written “to all the Labour MPs on July 24, lobbying them to use their influence to have this destructive and controversial bill removed from the ballot”.

Orr claimed its withdrawal was due to the lobbying, and said: “Right to Life now requests [Street] finally discards this bill and makes a commitment to the community to refrain from placing this contentious bill back in the ballot. This bill has no place in our Parliament.”

Peter Brown is a Christian. “Not a devout one,” he says, “but I try to live my life according to Christian principles.”

He notes that among the “hundreds of letters” he received about his 2003 bill were many supportive messages from Christians, but some of the most unpleasant were “standard letters” from religious people with comments scrawled at the bottom. Some were “very unChristian-like”, he says. “And the worst letters I got were from people who identified themselves as Catholics.”

Like Brown, Maryan Street is quick to emphasise that not all Catholics are opposed to voluntary euthanasia: “There’s no monolithic view on this by any group in society,” she says.

Nevertheless, whatever the rank and file think, the Catholic Church hierarchy vigorously opposes assisted suicide, which is hardly surprising given its prohibition on taking another human’s life; that it regards life as a gift from God and its natural course should not be interfered with; that suicide is a mortal sin; and that suffering is integral to the church’s teachings about salvation.

This last point is often overlooked in the debate about voluntary euthanasia, but was made vividly apparent to me in 2007 after my sister died in a Brisbane hospital tied to a bed, screaming in agony from cancer in her lungs, breasts and spine.

A few days after her death, a devoutly Catholic relative rang to say she had heard my sister had died in horrific pain and tried to console me by saying the good news was that her suffering hadn’t been pointless because she “wouldn’t have to spend much time in purgatory”.

Suffering is integral to the Catholic Church’s teachings about salvation.

She went on to explain that enduring suffering patiently on Earth is one way to cut your time in purgatory.

If you read around the topic, you’ll find that, according to the Catholic Church, anyone who isn’t going straight to hell has to be “purified” of unforgiven venial sins in purgatory before facing God.

Catholics advocate suffering as a way of sharing in Christ’s sacrifice of his life on the cross. In fact, it is so common to see a cross in the Western world that it’s easy for the unreligious to forget it is an instrument of torture, or that Catholic worship often takes place in front of a representation of a man being tortured to death on a cross. Suffering as a means of sanctification is fundamental to Christianity, and to Roman Catholicism in particular.

And not only experiencing suffering, but watching it as well, apparently. As Bill English, a practising Catholic, said in arguing against the 2003 Death with Dignity Bill in Parliament: “Pain is part of life, and watching it is part of our humanity. Many of us have become more human for watching it, whether or not we liked doing that.”

As well as regarding killing another person as a mortal sin, Catholics believe humans shouldn’t stand in the way of fulfilling God’s plan for them, which is one of the reasons the church forbids anything but “natural” methods of contraception such as the rhythm method or abstinence (even when condoms, for instance, can help prevent the spread of the HIV virus). Dying is another natural process, governed by God’s will, that shouldn’t be interfered with.

The strength of the church’s opposition was made clear in the Vatican’s Declaration on Euthanasia in 1980, which states: “Intentionally causing one’s own death, or suicide, is equally as wrong as murder; such an action on the part of a person is to be considered as a rejection of God’s sovereignty and loving plan”; and “no one can in any way permit the killing of an innocent human being, whether a foetus or an embryo, an infant or an adult, an old person, or one suffering from an incurable disease, or a person who is dying.

“Furthermore, no one is permitted to ask for this act of killing, either for himself or herself or for another person entrusted to his or her care, nor can he or she consent to it, either explicitly or implicitly. Nor can any authority legitimately recommend or permit such an action.”

No one, of course, disputes the right of religious people to live life to their last possible breath – and suffer excruciating pain along with it – if that is their wish. But why try to force that viewpoint on others?

As Zurich’s voluntary euthanasia clinic Dignitas says in its manifesto: “No one has the right to impose or even attempt to impose his or her individual ideological, religious or political beliefs on another. Muslims should not do it to Christians, Jews or Buddhists. Christians should not do it to Jews or those of other beliefs, and a believer should not do it to an unbeliever – not even using the indirect method of a governmental regulation.

“The state should be the guarantor for a pluralistic society and must forbid anything that would restrict this pluralism or lead it in a certain direction in the interest of a specific ideological viewpoint.”

In fact, we are so used to politicians shutting down the official debate, it’s easy to forget that what advocates of voluntary euthanasia are proposing is an action that takes place between two consenting adults.

Why the NZMA opposes voluntary euthanasia is an abiding mystery to many, just as it was to Dr John Pollock. In 2010, Pollock – a 61-year-old Auckland GP facing death from metastatic melanoma – wrote an open letter to New Zealand Doctor, which was also published in the New Zealand Herald. He noted that the association’s official position didn’t tally with his experience of talking to fellow doctors (and, for that reason, he had resigned as a member several years earlier).

“The New Zealand Medical Association is against euthanasia. To me this is unfathomable,” he wrote. “I have discussed it with many, many of my colleagues over the years and have found that the vast majority are for it. Indeed, I have met many who, at great risk to themselves, have succumbed to a patient’s begging for a merciful release.

“Is it really likely that the profession that sanctions the termination of the lives of thousands of healthy unborn babies each year would criminalise the shortening of the lives of suffering, dying patients who ask for that last merciful service?”

It’s worth noting that the NZMA is not the body that registers doctors. That organisation is the Medical Council of New Zealand, which looks after “standards, conduct and competence”. It has a neutral stance on voluntary euthanasia.

The NZMA is more like a union; it describes itself as the country’s “foremost pan-professional medical organisation, representing the collective interests of all doctors”.

It also boasts on its website of being “a strong advocate on medico-political issues, with a strategic programme of advocacy with politicians and officials at the highest levels” and that “our high profile and influence places us in a strong position to advance core health issues”.

NZMA policy on voluntary euthanasia is not formulated in consultation with local doctors. The NZMA board and councils are representative bodies, elected by members, but its chairman, Napier GP Mark Peterson, confirms doctors aren’t polled individually about their views.

While the question of whether voluntary euthanasia should be made legal for a dying person suffering overwhelming pain is easily agreed to by many when asked, it becomes a much more thorny debate once the net is widened.

Opponents of voluntary euthanasia quite rightly point out the difficult ethical questions involved in deciding who exactly should be covered by legislation.

Should it include those, for instance, without a terminal disease but who find life intolerable because of a mental illness that medicine cannot control? Or should anyone be able to instruct close relatives, by way of an advance directive, to ensure that they are euthanised when they get a disease such as Alzheimer’s and can no longer confirm that earlier choice themselves?

These are difficult propositions worthy of close analysis and debate, but it is the weakest (and sometimes plainly false) arguments against legalising voluntary euthanasia that are often the first deployed. A common one is asserting that palliative care has advanced to such a level that no one need feel overwhelming and uncontrollable pain.

John Pollock devoted part of his letter to identifying the arguments commonly used against voluntary euthanasia. The first of the “prevalent arguments” he attacked was: “Our medical services, particularly the hospice organisation, have the skills to take the unpleasantness out of dying and so euthanasia is unnecessary.”

Pollock didn’t accept this. “Breakthrough pain is common and its prevention requires constant medical attention, which is not often available,” he wrote. “We are not good with neuropathic pain.”

He added: “My cancer may kill me in a variety of ways, some very unpleasant and drawn out. There are several scenarios which I would find intolerable and should be able to opt out of but for our old-fashioned, ill-thought-out, cruel laws which force me to suffer to the end or kill myself.”

In fact, as journalist Jim Robinson pointed out in 2007 in his North & South article “A Fiery End” that focused on pain management for dying patients, “breakthrough pain” occurs in about 10 per cent of cancer cases, which means around 900 people a year die with pain that cannot be reliably controlled by available painkillers. Yet, the website of the Catholic Nathaniel Bioethics Centre states: “These days, no one need die in pain.”

And, of course, it is not just the problem of unbearable pain. People also die in other terrifying ways. Rodney Hide told Parliament during the 2003 Death with Dignity debate that his friend Martin Hames “had watched his mother die a terrible death [from Huntington’s] — a death where one loses one’s mind and loses control, to the extent that one cannot swallow.” Hames chose to kill himself in 2002 to pre-empt suffering that fate himself.

Hide, who supported Peter Brown’s bill, said: “If Mr Brown’s bill had been the law, Martin Hames would still be with us, I am sure. He would not have needed to take his own life, as he did.”

Last September, Canadian infectious diseases specialist Donald Lowe – who came to national prominence steering Canada through the SARS crisis in 2003 – made a video of himself a week before he died of a brain-stem tumour; it was posted on YouTube after his death.

Already debilitated, Dr Lowe spoke of his fears of being unable to swallow, eat, walk or control his bodily functions, and suggested anyone opposed to voluntary euthanasia who “could live in my body for 24 hours” would change their mind.

“Why make people suffer for no reason when there’s an alternative?” he asked. “I just don’t understand it.”

Another tack commonly used to argue against legalising voluntary euthanasia is to shift the debate from the use of voluntary euthanasia to its abuse. This is the “thin edge of the wedge” or “slippery slope” argument, which often leads opponents to invoke the spectre of the Nazis killing victims such as the mentally deficient – completely overlooking the fact the Nazis specialised in involuntary euthanasia. In fact, they were known for state-sanctioned murder.

This argument cut no ice with the dying Dr Pollock. “The thin edge of the wedge [argument] – if we allow voluntary euthanasia for the terminally ill, it won’t be long before we are killing the mentally ill, the deformed and everyone over 70 – is about as sensible as saying if we allow people to eat meat it won’t be long before we are eating each other.”

In fact, Pollock effectively reversed the argument, pointing out that under our present laws we allow people to die in “most appallingly wretched states, sometimes akin to those who died of starvation in Nazi concentration camps”.

Brown says: “The best argument against the ‘slippery slope’ is good legislation – sound, workable and totally voluntary euthanasia”.

It’s also worth pointing out that most nations, including ours, already have experience in regulating how people kill and are killed. In war, for example, there are strict rules against killing non-combatants (particularly women and children), and severe penalties for those who do.

If the state can make laws for how people conduct themselves amidst the terror and chaos of war, why is it so difficult to make laws that govern how we deal with those dying in the relative peace of a hospital ward, a hospice or at home?

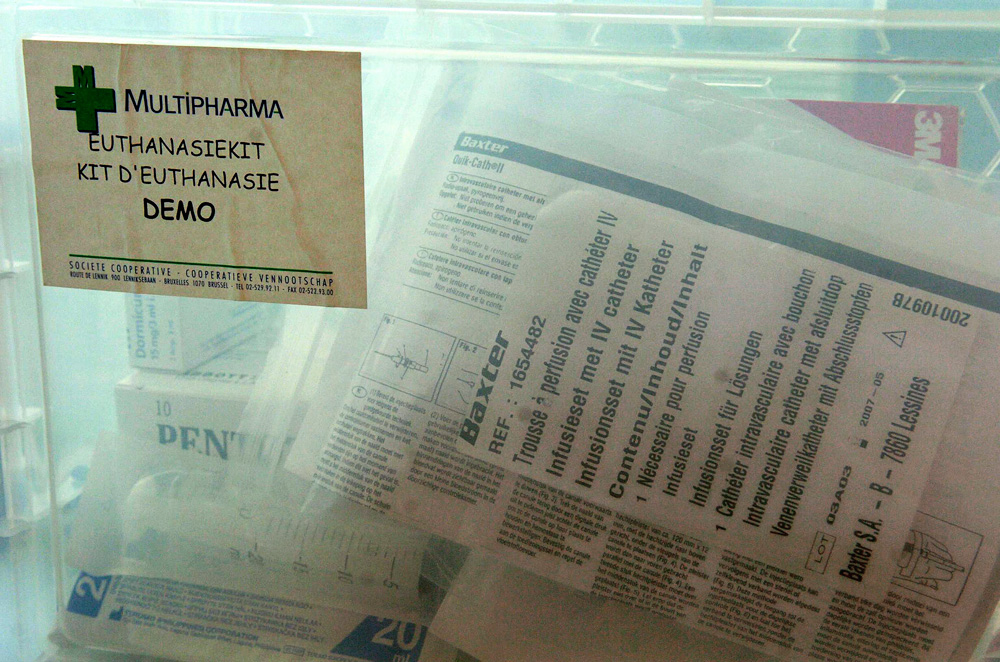

And we are hardly going to be pioneers in the field. Internationally, there are plenty of models of legal voluntary euthanasia to study, including four US states – Vermont, Oregon, Montana and Washington – as well as Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland, where the Dignitas clinic accepts patients from around the world because its staff believe it would be discriminatory to exclude those unlucky enough not to be Swiss citizens.

Perhaps one of the most interesting lessons comes from Oregon, where around 40 per cent of those given a lethal prescription don’t use it. the reassurance they can have a painless death is sufficient.

Perhaps one of the most interesting lessons comes from Oregon, where around 40 per cent of those given a lethal prescription don’t use it. For them, the reassurance they can have a painless death is sufficient.

Yes, you can always kill yourself – or at least try – but as Pollock wrote: “The law won’t be changed in time for me and the only way that I can legally end my life before it is due to end is suicide and that’s the cruelty of it – not only suicide but suicide alone, because if I top myself with my family present then I put them at risk, and I think that’s hideous. It’s very cruel.”

Maryan Street paints that cruelty in vivid terms: “Why did Rosie Mott have to send Evans out to the supermarket and for him to have to wait until the texts stopped coming? Why couldn’t he have been with her when she died?”

Terminally ill people often end up using extreme ways to kill themselves too, although details of their final moments are usually suppressed.

Last May, a coroner found that devoted Paekakariki couple Adrian and Marei Webster, both in their 70s, had died in a suicide pact, but banned publication of the manner of their deaths. Adrian, a local body politician, had terminal stomach cancer. Handwritten suicide notes were found, but it was unclear whether they were parties in each other’s deaths or just their own.

Some voluntary euthanasia advocates now operate an underground movement with advice on how to kill yourself as painlessly as possible. But, as Dr Pollock noted, anyone suspected of having a hand in the suicide, including even providing materials such as helium and plastic bags, risks being charged with aiding a suicide even if they are not present at the time of death.

If the nation developed a well-regulated and entirely voluntary euthanasia policy, such desperate subterfuge for those in unbearable agony or distress would not be necessary.

Peter Brown says he was very disappointed by Maryan Street withdrawing her bill. He thinks she may have done so because Labour didn’t want to risk further antagonising middle New Zealand after same-sex legislation came into effect last August as a result of Labour list MP Louisa Wall’s member’s bill being drawn from the ballot.

Or is the reason much simpler – that Street knows Labour will put forward a government bill if it wins the next election?

She has said publicly that is her hope, while denying a deal has already been done with party leaders. “I don’t have a cast-iron undertaking from anybody that that will happen but I will certainly agitate for it.”

She is “keen to promote it to her caucus colleagues, but still as a conscience vote, obviously”.

Asked if she would like it to be a govern-ment bill, Street replied: “Ideally, yes, because it would take the capriciousness out of the situation.”

When I emailed David Cunliffe and asked: “If Labour is in a position to form a government after the next general elections in 2014, will such a bill be proposed by your government?” he replied enigmatically, “This has traditionally been dealt with as a conscience matter. There is no bill currently before us at this time.”

When a bill is eventually presented – either as a member’s bill or as a government measure – Street has no doubt that “a well-resourced, vocal minority”, whose position is “informed more by their theology than anything else”, will “pull out the big guns”.

But she has been “working steadily over the past 20 months”, organising meetings to discuss voluntary euthanasia and getting turnouts of 300-400 in the big cities and 50-120 in provincial centres such as Hamilton, Nelson and New Plymouth.

Street says she is trying to “create a solid groundswell so that people are talking about the issue and coming out of the woodwork and lobbying their MPs.

“And at every turn I am finding a majority in favour,” she says. “In the end, the vocal minority will not be able to contest all of that.”

Ending a Life

Is withdrawing the necessities of life simply euthanasia by another name?

It had felt like the right decision, back at the rest home, when her elderly mother signed a form declining medical intervention if she became critically ill. But as Rebecca sat by the hospital bed watching her die, and the days stretched into a week, the reality of what that choice meant left her shaken.

Unable to swallow, her mother had been given no food or fluids, and the restlessness that saw her plucking compulsively at the bedding gradually diminished as her body weakened. By the sixth day, it was clear she would never regain consciousness from the massive stroke she’d suffered in her sleep.

“That would have been a good time to let her go,” says Rebecca, who wanted to be with her mother when she died. “I knew she wouldn’t want to continue in a vegetative state. It felt cruel, as if she was sort of trapped. But you can’t choose to be gently swept away on a cloud of morphine. That seems like a more humane scenario than allowing her to dehydrate to death.”

Even if voluntary euthanasia were legalised, what would happen in situations like this, where the dying are unable to communicate their wishes? And is there really a difference between withdrawing the necessities of life and stopping someone’s heart with a lethal injection?

That’s a common misconception, says Anne Morgan, practice adviser for Hospice New Zealand. She’s worked in oncology and palliative care for more than 30 years, and sees Rebecca’s experience as an example of how poorly end-of-life care is sometimes communicated to the family and how ill-prepared we are to deal with the process of dying.

After a massive stroke causes severe brain damage, or when a terminal illness reaches a critical point, the body’s organs are no longer able to function and naturally begin to shut down, Morgan explains. The kidneys are often first to fail and would be unable to cope if fluids were given intravenously.

The kidneys are often first to fail and would be unable to cope if fluids were given intravenously.

“There are very clear indicators that any treatment is no longer useful, but would be a burden on the body and cause distress,” she says. “After a major medical event, such as a stroke or advanced disease, that’s what the person dies from – not dehydration.

“It’s like a motor shutting down. The breathing slows and finally the heart stops and comes to rest.”

Hospice New Zealand’s official position is that it does not support a change in the law to legalise assisted dying in any form, but follows the World Health Organisation’s definition of palliative care – “neither to hasten nor postpone death”.

Individual end-of-life plans are talked through with each patient, including where they want to be cared for, their spiritual needs and the choice to refuse treatment. Most commonly, people want reassurance they won’t be in pain, to have their family around them, and not to be kept alive by artificial means.

“The debate that needs to be happening in the public arena is about having those good conversations with your family before you get sick,” Morgan says. “An acute situation is not a good time to be making such decisions. There are formal ways to do that, with advanced care plans, but it can also just be a dinner-time conversation.

“I think the reason the euthanasia debate has reared its head in a way is because medical technology has gone ahead so rapidly that we can now keep people alive. And a lot of the conversations around it are quite emotive. But dying is actually a normal process for the body. It knows how to do it. With good support, it will do it very well. For the family, it’s a very sad time, but there’s a beauty in that sadness and a lot of honesty.”

– Joanna Wane.