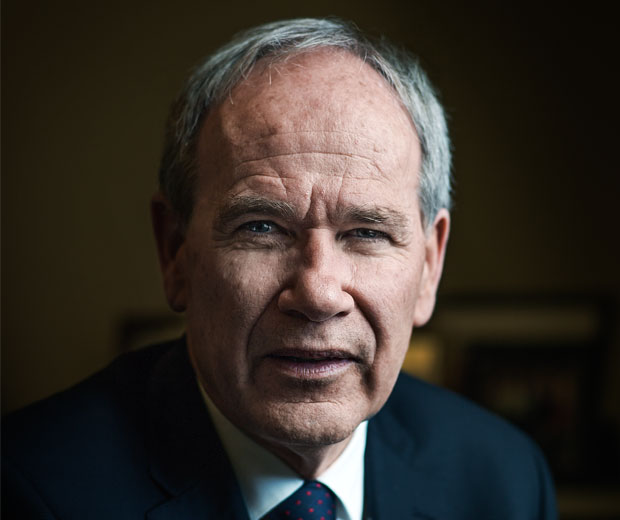

Oct 31, 2016 Politics

It was the very last day of debates on the Unitary Plan (UP), the culmination of his political life. A good day to be Len Brown. He knew that when he left office in just a couple of months, he could do so with a sense of great achievement.

It wasn’t the single biggest event of his political career — beating John Banks’ million-dollar campaign to win the first super-city mayoral election in 2010 probably takes that accolade. But it was a satisfying full stop.

Brown was a mayor who raised himself up, and his city too, with vision, skill, toughness and triumph. And brought himself low with humiliating absurdity, political and personal isolation and, worst of all, a myopic inability to understand the sense of confusion, ineptitude and squandered opportunity he left in his wake.

The comfortable view is that history will look more kindly on him than we do now. Perhaps. Len Brown achieved far more than he was expected to in his six years as Auckland’s mayor and he left the city far better than he found it. He also betrayed his colleagues, brought ridicule not just on himself but on his office and the wider council, and lost the respect of many who worked around him.

He spent his last weeks in office telling anyone who would listen that his “personal problems” made him a better mayor. That’s delusional, which in itself was a weakness Brown was always susceptible to. His sex scandal ruined his ability to act effectively. Because of it, when it came to the task of remaking Auckland as a progressive city of the 21st century, the task he had once championed, he became in several key respects an impotent bystander.

Should Brown really have been so jovial that winter morning? Just one day earlier, without warning, Brown had got out a big knife and stabbed his loyal deputy, Penny Hulse, in the back. Well, he might as well have.

They had met earlier, as was their custom during the days of the UP debate, to agree on their strategy. Hulse had been Brown’s deputy for the entire six years of his mayoralty, never once speaking out against him, despite being personally appalled at his behaviour. She was the person he relied on to get majority support for his programme.

She was also, as chair of the Auckland Development Committee, the councillor principally responsible for steering the UP through the long and often harrowing political process. It was Hulse, not Brown, who fronted up to most of the angry public meetings, who worked most closely with council officials on the details and wrangled the local boards and other councillors.

The issue that August morning had been affordable housing. The vote was about whether a particular provision of the UP should include a quota for major developments. They were on the same side: both wanted more affordable housing built in the city. But Hulse believed that goal was already safeguarded and would not be further helped by an extra clause. Brown, it turned out, wanted to make a gesture.

In their morning meeting, he had not told her that. She thought he had her back. But in the council debate he made her look like she didn’t care. He reduced her to tears. It had been shaping up as a good day not just for Brown’s council leadership, but for Hulse’s political skill and nerve in shepherding the whole thing to fruition. He destroyed that. When it was over, he was not only unrepentant, but seemed unaware of what he had done.

Brown was elected to great fanfare in 2010. He was the first mayor of the new super-city, which combined eight councils into one to form the largest local body in Australasia. He wasn’t expected to win. The amalgamation had been driven by Local Government Minister Rodney Hide, with strong support from the rest of the National-led government and with most opposition coming from various political forces on the left. Including Brown, a Labour Party member in his first term as mayor of Manukau City. At that stage, he didn’t have higher political aspirations: he was the mayor of Browntown, “down with the brown”, a man who loved and felt deeply connected to the south.

Then they went and took it all away. No more Manukau City. It was hard not to see his bid to become mayor of all Auckland as the only course open to him if he wanted to remain mayor of Manukau.

He unleashed his political smarts. Bob Harvey, the very popular mayor of Waitakere, wanted the new mayoralty, and so did Mike Lee, chair of the Auckland Regional Council. Harvey was a vastly experienced politician and former Labour Party president, and Lee was the de facto leader of the left across the wider Auckland region. But Brown finessed them both by securing the support of the Labour Party, and with it the services of an invaluable organising machine.

One day earlier, without warning, Brown had got out a big knife and stabbed his loyal deputy, Penny Hulse, in the back

Harvey and Lee were furious. They both knew there could be only one centre-left candidate and did not run against him. But neither man ever came to respect him.

The new councillors, on the other hand, looked at first blush to be an ungovernable bunch of entitled elders from the old councils. Many had themselves been mayors or chairs of important committees; none was interested in being kept in line through a caucus system.

On the right, there were several councillors, including Christine Fletcher and George Wood, who plainly thought they could do a better job of mayor than Brown. His left flank, featuring the brooding Mike Lee and Sandra Coney, was similarly open to attack.

And yet Brown dispensed committee chairs and other favours with aplomb. In choosing Hulse as deputy, he shrewdly opted for a soft-spoken but very determined Westie, who for good measure had been Harvey’s deputy at Waitakere.

Brown wasn’t a collaborator, not in the wider sense: after they were all elected in 2010, it took him six months to get around even to meeting the chairs of the local boards. But with the help of Hulse and his finance committee chair, the former Rodney mayor and Act Party MP Penny Webster, Brown created at that council table something quite remarkable: a consensus for his “liveable city” programme based on moderate councillors of the left and right.

In 2012, he and Hulse steered the Auckland Plan through the council. It’s the foundation document of the new combined city, setting out a 30-year vision, a declaration of how good Auckland could be. It’s easy to forget that until at least 2010, the prevailing mood in Auckland was cynicism.

That same year, Brown established the council’s first Long Term Plan, a 10-year declaration of spending priorities. He began the politically delicate process of unifying rates and oversaw the largely successful transition of the eight old council operations into one new one.

He got the government to take him seriously. The turning point for that came a year into his tenure, with the Rugby World Cup — although it didn’t seem like it at the time.

The opening day was a fiasco. Transport systems collapsed, most people couldn’t get close to the entertainment and there were enormous, restive crowds on Quay St, Queens Wharf and lower Queen St. Being in the middle of that seething, confused mass of people was scary: panic seemed just one misjudged shout away and if it had happened, the outcome would have been disastrous.

The opening day was a fiasco. Transport systems collapsed, most people couldn’t get close to the entertainment and there were enormous, restive crowds on Quay St, Queens Wharf and lower Queen St. Being in the middle of that seething, confused mass of people was scary: panic seemed just one misjudged shout away and if it had happened, the outcome would have been disastrous.

The government blamed Brown personally, although the entire operation had been controlled by Rugby World Cup Minister Murray McCully.

Brown was impressive: he sucked up the bullying without complaint, got everyone to learn the right lessons from the day and, as the event unfolded, he made sure Auckland enjoyed the party. He was, in other words, a proper leader. The government took notice.

He’s unflappable, Len Brown, and it’s a core strength. “Aw look,” he liked to say, “you win some and you lose some, but you set yourself steady goals and you keep moving forward.” He spoke in clichés, almost always, but those clichés did accurately describe what he did.

The city is full of people who thought Brown was going to help them do something great and it just never happened.

But then he would go back to his office, his head full of those ideas, and do nothing about any of them. The city is full of people who thought Brown was going to help them do something great and it just never happened. The flip side of Brown’s unflappability, it turned out, was inaction.

Auckland churned with creative energy. Opening up the waterfront, the creation of thrilling public spaces and engaging downtown architecture, the extraordinary revolution in public transport, the enormous boom in restaurants and cafes and bars, the genuine re-emergence of cycling, the Southern Initiative and all the programmes designed to lift up the south: in short order, Auckland had become a very exciting city.

Brown didn’t invent it. The “liveable city” project is not unique to Auckland — in fact, it’s the norm all over the world. But he did play an important role. He was our happy champion. And then the unthinkable happened.

The news that Len Brown had been having an affair with a member of the council’s Ethnic Peoples Advisory Panel broke just days after Brown’s triumphant re-election in October 2013. Not just the news; courtesy of blogger Cameron Slater, we learned every sordid little detail.

Brown brazened it out. His second inauguration, also a big occasion in the Town Hall, was distinguished by a constant chorus of “Shame! Shame!” It wasn’t the dignitaries and community representatives shouting at him, it wasn’t even people outraged at the scandal. The disruptors were protesters from Glen Innes furious that the council was standing by while state-house tenants were being evicted and their homes carted away on trucks.

In the weeks that followed, however, there were constant protests about the scandal. Small groups followed Brown to every event: some of them conservative Christians who were genuinely offended, others far-left activists like Penny Bright, who cannot have cared two hoots about the mayor’s sex life but jumped on the bandwagon anyway.

I thought he would resign, but what I hadn’t realised is that he has the hide of a rhinoceros. He stayed in office and steadily sank from sight. He dropped his Mayor in the Chair sessions, regular events in which he went to suburban shopping malls to hear whatever it was people wanted to tell him or ask about. He’d loved those sessions, but not when they took on the character of a pillorying in the stocks.

His diary shrank. Schools, business groups, ethnic groups — who wants to hear a speech by a philandering nitwit? And he stopped leading from the front on the big project of transforming the city.

He took some leave, but when he came back, it hardly made a difference. Brown was lost at sea throughout 2014. The job of running the council fell to Hulse and the new chief executive, Stephen Town.

There’s a view that it didn’t matter much, because the important work had been done. That’s patronising to the work Hulse did, and besides, it’s simply not true.

The year 2014 was the year of the great public consultation on the draft Unitary Plan, which proposed an end to Auckland’s postwar planning philosophy, based on suburban expansion, in favour of creating a more compact city. Winning the public to that vision wasn’t easy, and night after night at public meetings with citizens worried their suburbs would be destroyed, it was Penny Hulse who led the charge. She has described some of those meetings as the hardest moments of her political career, but she kept going. Brown hardly ever appeared.

Meanwhile, Town set about reforming the way the council worked. His focus was the business operations, the council-controlled organisations (CCOs) that he referred to collectively as “the family”.

It was a big task: there are some very different ideas about direction, priorities and responsibilities among the CCOs, especially between Auckland Transport and Waterfront Auckland (which has now merged with the council’s property company to become the citywide agency Panuku Development Auckland).

Town’s family table, a co-ordinating committee of the heads of the CCOs, did not have any elected members and did not report to Brown or the council. In effect it was, and still is, a parallel power structure to the office of the mayor and to the governing body of the council. That says a lot about how weak Brown had become.

Worse, while Brown was excluded from important decision-making, he was also confused about what to do when he did find out what was going on.

In late 2014, Ports of Auckland Ltd (POAL) was granted consents to expand further into the Waitemata Harbour. Despite massive public interest in the issue, no one told Brown. And when he did find out, he equivocated, blustered a bit and then supported the move. It took a private action by the lobby group Urban Auckland to get the High Court to declare the consents were improperly issued.

In late 2014, Ports of Auckland Ltd (POAL) was granted consents to expand further into the Waitemata Harbour. Despite massive public interest in the issue, no one told Brown. And when he did find out, he equivocated, blustered a bit and then supported the move. It took a private action by the lobby group Urban Auckland to get the High Court to declare the consents were improperly issued.

A good mayor fronts in a crisis. A mayor with his heart in South Auckland, you might think, would have been all over this one.

Brown didn’t know about AT’s plans and opposed them when he did find out. It was an astonishing episode. How was AT possibly able to make such a major announcement without involving the mayor? How did the council not hold Auckland Transport to account when it found out?

And how was it that Len Brown, champion of the liveable city, did not want to prioritise light rail anyway?

As Brown’s second term wore on, his isolation grew worse. The council bought an office block downtown without doing the due diligence required to identify that major repairs were needed. Brown was out of that loop. Just before the election, AT revealed the cost of the City Rail Link would be higher than expected. Again, it was news to Brown.

Even since the election, council agencies have continued to keep the mayor — now Phil Goff — in the dark: POAL applied for a consent to put a three-metre-wide walkway 65 metres into the Waitemata without talking to him.

Plainly, there are senior officials who believe the mayor should not be consulted or advised on important decisions. What role has Stephen Town played in that? Let’s put it this way: he should not have let it happen and Brown should not have allowed him to let it happen.

Meanwhile, the council and the government made slow progress on housing, with much less construction in their “special housing areas” than was expected. The council’s favourability rating with the public fell to just 15 per cent. The recent elections were conducted in a general atmosphere of crisis, with the prevailing view that Auckland was a mess.

What a contrast from just three years earlier, when progress on the liveable city and Brown’s infectious enthusiasm created an environment of optimism and widespread satisfaction.

That’s the real impact of Brown’s sex scandal: his failure to lead from the front for the past three years has led to a collapse in public confidence. The mood of the city has changed. Brown reduced his goals to staying in the job and winning the key numbers, and he achieved those aims. But the collateral damage was severe.

He did, to his credit, get the government to approve the City Rail Link. At the start of his first term, that looked like an impossible goal and it’s an immense achievement he should be proud of. Did it warrant his staying in office when in so much else he was so ineffectual?

I’d say no. By the time of his second term, Brown had already put in place the conditions to win government support for the CRL. Another mayor would have been able to build on his good work in that first term to get the job done.

And the homeless crisis? The council didn’t create it and it couldn’t, on its own, fix it. But when the issue blew up, Brown was nowhere to be seen. A good mayor fronts in a crisis. A mayor with his heart in South Auckland, you might think, would have been all over this one.

Brown could have galvanised more support more quickly, and thus made a material difference. He could also have channelled the much wider sense of community frustration that such things happen in our city. A leader who becomes a conduit for popular desire to make things better is doing their job well. But Brown was already on his way to retirement. Mentally, he had checked out.

Brown could have galvanised more support more quickly, and thus made a material difference. He could also have channelled the much wider sense of community frustration that such things happen in our city. A leader who becomes a conduit for popular desire to make things better is doing their job well. But Brown was already on his way to retirement. Mentally, he had checked out.

Abuse of his position? He was a powerful man who got sexually involved with a young woman whose role on the council he had a say in. Yes, definitely that.

Abuse of the office? Oh Len, not the Ngati Whatua Room. That hurt, too.

Abuse of his council credit card? An inquiry — which Brown was forced to help pay for — found no evidence of financial misconduct, although he did benefit from hotel-room upgrades. Unwise, perhaps, but not illegal.

Being stupid? How did Brown not understand the risks he was taking? Did he think he was immune to scandal? Did he not grasp that sooner or later he would be found out? Or did he just not even think about it? Which one of those answers doesn’t make him look like an idiot?

Being ridiculous? If Brown had been revealed as having an affair, without us learning the sordid specifics, he would probably have survived with his reputation largely intact. Cameron Slater, who published the story on his Whale Oil blog, knew that. It was the details that destroyed Brown because they were so appalling vivid. He embarrassed us.

Fundamentally, his sin was to get caught. He revealed himself incapable of doing what most people do with potentially humiliating absurdities in their private lives: keep them hidden.

I’ve seen Brown speaking at a black-tie event in the Aotea Centre, more than two years after the scandal broke, where guests stood about in their gowns and jewels and kept up a sniggering commentary about “Pants-down Brown”.Discretion is a measure of competence, a mark of fitness for public life. Brown failed the discretion test, and that’s what made him despised.

The council debated a motion of no confidence, which would not necessarily have forced him from office because the mayor is accountable to the voters, not the other councillors. But it was a means for councillors to tell him publicly what they thought.

It was a tense debate. As they spoke, many of the councillors made it clear they had indeed lost confidence, but would not vote for the motion because they were prepared to allow Brown the dignity to determine his own fate. They voted not to humiliate him further, on the assumption that he would do the decent thing and resign anyway. Brown, with that rhinoceros hide, sat tight.

He was good with people. Liked to chat, and liked to sermonise, too. His MO was to adopt the style of whatever religious leader was appropriate to the group. I’ve seen him do evangelical populist, doctrinal Catholic, liberal Anglican, Baptist pastor, born-again fundamentalist, Mormon leader, Destiny firebrand. Around the council table he was the patient but slightly exasperated patriarch. He must have thought, in simpler times, that he would one day be known as Father Brown.

The religious aspect of his popular base makes his refusal to resign all the more surprising. Not the fact of the affair — sexual hypocrisy is a common failing of religious conservatives — but the way he brazened it out.

It was one thing for Brown to stare down the tut-tutting of the eastern suburbs — they didn’t vote for him and never would — but quite another for him to stand in front of the congregations of South Auckland and pretend he had not let them down.

How did he cope with their dismay? He ignored it. Despite his deep and genuine connections to the city’s Pasifika, Maori and migrant communities, when it came down to it he betrayed their values and decided he could live with that.

It’s not a good thing in politics to have the hide of a rhinoceros. When you’re immune to criticism, you’re not going to make good judgments about what’s acceptable.

And yet, even to the end, he had some wonderful days. On the morning of September 22, Len Brown was the last of six speakers at the official opening of the ASB Waterfront Theatre. Most of the others stumbled through their official speeches.Brown began with a lengthy mihi, delivered in Maori without notes, and then launched into a heartfelt and lyrical tribute to the Auckland Theatre Company (ATC) and the value of the cultural sector to the city.

He talked about the “flowering and uniting” of Auckland, and about the “grand dames”, the patrons and philanthropists such as Dayle Mace, who “sat in my office” and made him understand the importance of the theatre to the city. “Lester, we love you,” Brown said, referring to Lester McGrath, the general manager of the ATC, who steered the whole project. Most men still don’t say that in public about other men. “Thank you from the bottom of our collective hearts.”

Then he said, “This could be the last time I do this,” and walked out from the lectern to stand downstage centre. And there, in front of 500 members of the city’s sophisticated cultural set, he sang “Karu Karu”, a song about fishing which is really about hopes and dreams of what is to come.

Several people joined in. He was great. His speech had been laden with the kind of oratorical flourishes and emotive intent that almost every other New Zealand politician these days makes a point of avoiding. But his song was even better.

I’ve watched Len Brown make speeches and sing songs for years. He can be gauche, laughable, tedious but also inspired. He hung on to “Pokarekare Ana” as his song of choice way longer than he should have, but the singing was always good.

More than that, it said something. It said a lot of things. That he respected talent and that he had some himself. That he connected with Maoritanga in a meaningful way.

That he wasn’t afraid to enjoy himself in public. That of all the ways public figures get to show off, singing is surely one of the best.

He said to them all, “If I can do this, a scrawny white boy from Howick, if I can be mayor and stand here and sing for you, what’s not possible for any of you?”

To sing in public, unaccompanied, is to express the best of yourself. To be brave and to risk everything.

When Brown did it, he placed himself at the mercy of every person in his audience who might want to laugh at him, and sometimes they did.

He said to them, to all his audiences but especially to the ones he cared for the most, those kids in Browntown, “If I can do this, a scrawny white boy from Howick, if I can be mayor and stand here and sing for you, what’s not possible for any of you? If you’ve got a dream, don’t let the fear of what other people might think stand in your way.”

It’s such good advice for singing. It doesn’t apply if you really do disgrace yourself.

This article originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of Metro