Oct 28, 2014 Politics

After three student deaths within three months, King’s College has been the focus of unprecedented media interest. And the school, which charges parents up to $31,000 a year to have their children attend, is vigorously protecting its reputation.

First published in Metro, July 2010.

Feature photos by Adrian Malloch.

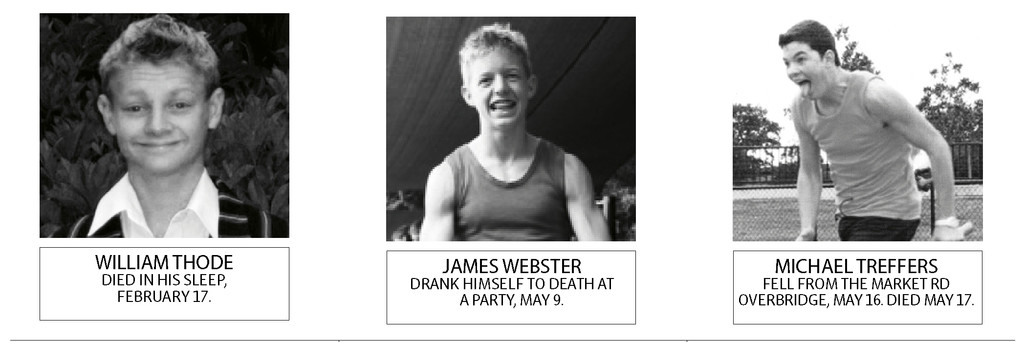

For a private school, it was a very public mourning. White shirts, striped blazers, red eyes. Square shoulders hunched in prayer, stiff upper lips trembling. Stained glass; tear-stained faces. A pale-faced haka. And all of it caught on camera. Once, twice, three times, for William Thode, James Webster and Michael Treffers.

Three deaths in three months would have made headlines at any school — but at the country’s most expensive private college, King’s, it seemed almost inconceivable.

Like Elim Christian College after the Mangatepopo deaths in 2008, King’s seemed, at the start, to embrace the attention and the community support. Television cameras were invited into the school grounds in South Auckland, pupils were interviewed, funerals recorded.

Within a day or two of Metro beginning to research its story on King’s — and before we contacted the school — headmaster Bradley Fenner emailed us saying he understood the media interest and was happy to be interviewed.

By the end of our investigation, however, Fenner had written a terse letter warning us off our lines of inquiry, urging us to be sympathetic and considerate in our approach and refusing us access to staff who dealt personally with the three boys.

We wanted to ask Fenner about allegations of a personality clash between Michael Treffers and a house master. We wanted to know the reasons for the teen’s highly unusual change of “house” at the school. And we wanted to discuss whether the college could have been more vigilant after Michael was taken to hospital with a drug overdose — just a week before his fatal fall from an overbridge onto the Auckland motorway.

Fenner said our questions were potentially defamatory and it was inappropriate for him to answer.

Now, as the college comes to terms with its losses, parents and staff have closed ranks around the school, the alma mater of the (mostly) moneyed and powerful. Even one parent who withdrew her sons because of alleged bullying wouldn’t talk to us, for fear it would harm their future prospects. It is this strong and tight-knit network of like-minded souls on a trajectory to success that drives King’s and, for the past 100 years, has set it apart from the rest.

Once a King’s boy, always a King’s boy. Take the case of trouble-prone barrister Eb Leary this year.

After money-laundering charges against him were thrown out in court and his name suppression lapsed, letters were published online from some of the 52 lawyers who supported his readmission to the bar after he was struck off over the Mr Asia affair more than 20 years ago.

Twenty per cent of them were written by lawyers who, like Leary, were former pupils of King’s. A couple, such as that from Auckland barrister Roger Chambers, referred to their bond from schooldays in their references.

The loyalty endures, says Chambers, because of the comradeship forged by boarding and by the house system — the generations-old symbols of affiliation and competition into which students are grouped from their first day to their last. Today, with more than 40 per cent of its roll boarding — 13 times that of another Auckland private secondary, St Kentigern — that spirit remains.

King’s, says Chambers, was set up for the sons of merchants and high achievers. “It was directed in large part towards those who had the opportunity to advance in a particular circle. It was set up for the sons of people doing well.”

He went there because his father and uncle did. Like his brothers, he was booked in on the day he was born.

In those days, in the 1940s and 1950s, the roll was peppered with names like Hellaby, Caughey, Spencer, Nathan and Myers. Later it was Huljich, Stiassny, Foreman, Richwhite, Key and Banks.

There were three main groups of boys, recalls John Harré, former dean of arts at the Auckland Institute of Technology (now AUT): the sons of the wealthy Auckland business community and highly paid doctors and lawyers, the sons of farmers, and the sons of educationally aspirational middle professionals such as teachers and clergy who “scraped and saved” to send their children to King’s.

Today, there are fewer sons of the land because of the sheep and beef sector downturn, but the school is promoting itself vigorously at A&P shows and field days to attract more rural boys. It also wants to increase the number of scholarships it offers, and to boost its Maori and Pacific intake — currently just eight per cent of the 970 roll.

The three boys who died this year, all boarders, each represented a segment of the new King’s student body. James Webster, 16, who died apparently of alcohol poisoning after downing a bottle of vodka at an off-campus birthday party in May, was an out-of-towner, the son of Thames manufacturing company director Charles and his wife, Penny.

William Thode, 15, who died suddenly of an undiagnosed heart infection in February, hailed from Remuera — his parents chose King’s for their boys despite living in the Auckland Grammar zone.

Michael Treffers, 15, who was being raised by his mum, Donna, after her marriage to Michael’s father, Alex, ended 10 years ago, was a scholarship boy: the school offered to pay his annual boarding fees when he excelled at the entrance examinations.

Alex Treffers, who runs his own business in Hawke’s Bay as a specialist satellite technician, admits feeling torn when Michael won his place at King’s. The $20,000-a-year tuition fees were a “huge financial burden”, but he says his former wife wanted to give her son — the dux of his primary school — the best possible education.

The boy from Ramarama had his problems fitting in at King’s, where he was a boarder in Parnell House. “In the beginning stages he was pretty reluctant [to go]. I think he found the communal living pretty tough.”

In a warm and humorous eulogy, teacher Schalk Van Wyk told mourners at Michael’s funeral that he’d been part of the interviewing panel who’d accepted his application for King’s in Year 9. “I must confess there were times I wondered if I’d made a big, big, big mistake.”

The smiling 11-year-old from South Auckland had morphed into “a headstrong teenager determined to test the very limits of the patience of those who ran the house”.

At the start of this school year, Michael moved from Parnell to Selwyn House, where William Thode died just weeks into the term. In a school built on loyalty to the brotherhood of the house, Michael’s move was a rare and significant step.

Alex Treffers says the problem was a personality clash between his son and Parnell housemaster Chris McLachlan. “Those two were like a red rag to a bull,” he says. There were a “couple of silly incidents” — one when Michael took his laptop into a prep class, which was against the rules. He had it confiscated for a week — only to take it straight back into prep class when he got it back.

“Michael probably saw Mr McLachlan like a parent — someone you could maybe push a little bit.”

King’s chaplain Warner Wilder says house changes at the school for pastoral reasons are so rare they can be counted on one hand and a personality clash is “invariably” to blame. Michael got on well with his peers, says Wilder, but there “could well have been” a clash with McLachlan.

Early in May this year, Michael was taken to Middlemore Hospital after overdosing on anti-inflammatory pills he’d been prescribed by a family doctor for neck and shoulder pain.

Alex Treffers is adamant it wasn’t a suicide attempt — Michael told him he took the pills as a dare. He was taken to hospital when he became dizzy and had blurred vision. He was made to vomit and given counselling, says his father, and was discharged after about seven hours.

“He said it was an accident and he apologised — that he was a bit stupid and shouldn’t have done it. But boys being boys, they thought they’d try this and see what happens. It was definitely a dare, it had something to do with biology class, where they were studying the ill-effects of certain drugs on your body. I’ve never had the feeling he was going to harm himself. He’s pretty known for doing stupid things.”

About a week later, on May 17, Michael died of head injuries the day after falling backwards from the Market Rd overbridge into the northbound lanes of Auckland’s Southern Motorway. Alex and Donna Treffers believe that, too, was an accident, a silly mistake that cost him his life.

The night he was fatally injured, Michael had been visiting his close friend Luke Farraday — also a Parnell House student at King’s — in Remuera. He’d gone there to collect a letter Luke had been given by Michael’s girlfriend of three months, a student of the private girls’ school St Cuthbert’s, who lived near Luke.

Alex Treffers, who’s read the letter, says she was explaining to Michael that they shouldn’t keep sneaking out at night to meet up — hijinks that had got them into trouble with Michael’s mum that same weekend. But, the father says, she wasn’t breaking up with him and, when he spoke to Michael on the phone at 10.10pm, just 20 minutes before he fell from the bridge, he wasn’t upset.

“I would have talked him out of it if he had been. He was still at Luke’s. I just told him he ought to be getting home.”

As Michael was cycling home to Manukau Rd, where the family had shifted from Ramarama to be closer to town and so his sister Sophie could attend Epsom Girls Grammar, he stopped on Market Rd and texted Luke.

Apparently, says Alex Treffers, Michael would often sit on a ducting pipe over the bridge railing and smoke cigarettes. “I’m not sure but I think he said something like, ‘What would happen if I jumped off the bridge?’ I think he was just having him on to see how quickly Luke would appear at the bridge. But if you’re going to jump, you just do it, don’t you?”

By the time Luke arrived, Michael had fallen and all Luke could do was call an ambulance for his mortally injured friend.

Alex Treffers believes Michael had scaled the bridge railing but slipped as he tried to stand on the ducting pipe.

He says it’s possible Michael felt “different” from some of the other boys at King’s — it’s something they might have talked about one day — but in his last months at the school he was thriving.

“He was a loving boy. A little naughty, a little mischievous. Personally, I’ve had a lot of near-misses, a lot of chances in life, but he didn’t even get one.”

Chris McLachlan announced his resignation from King’s before Michael Treffers’ death. Asked if he and the student had had a personality clash, McLachlan said he would not comment out of respect for Michael’s family. “I have a very positive relationship with his mother and I don’t want to say anything.”

Although he was house master and responsible for such matters, he said he didn’t know what had caused Michael to change house. Headmaster Fenner refused to comment on McLachlan’s resignation or allegations of a personality clash. Wilder told Metro the teacher’s departure was coincidental.

Fenner was recruited from Adelaide a year ago. A church-going Christian, he says he doesn’t under-estimate the role of the church in the spiritual life of the college and its recovery from the boys’ deaths.

Every student attends chapel twice a week for services usually led by Wilder, who’s been at the school for 21 years.

Wilder set up the school’s community service programme, which regularly involves 500 students in outreach work, including volunteering in Middlemore Hospital and reading at local schools. He also puts about 300 pupils each year through the spiritual and religious-based Voyager programme. About 15-20 per cent of those pupils go on to be confirmed in the Anglican Church.

“As I’ve said to students a million times in chapel,” says Wilder, “I don’t mind how wealthy you finish up being, or what positions of authority or power you attain, if you (a) do that at the expense of your fellow human being or (b) to the exclusion of relating to and caring for your fellow human being, I honestly don’t believe you will ever feel fulfilled and happy.”

He says that though no school will ever suit everyone, he’s happy that King’s is providing an education that helps students feel nurtured “but at the same time inculcates in them a desire to nurture other people — that they are not totally focused on their climb up the ladder, whatever ladder that might be”.

While some parents told Metro that part of their desire to send their children to King’s was to provide a peer group that would open doors throughout the rest of their careers, Wilder doesn’t believe that’s a key reason.

Fenner says while he can’t comment on parents’ individual motivations, “certainly I hear from parents that they like the sort of friends their children make here, they like the quality of the young men and women, they like their values and the way they conduct themselves”.

King’s students, though, have never been immune from the drugs and bullying that curse most schools, regardless of their decile ranking. In the 1990s, six students were expelled in a marijuana bust. These days, around two students are expelled each year.

Fenner refused to comment on the expulsions, claiming it was a “privacy matter”.

One parent of students who have left the school told us bullying was endemic at King’s, particularly at junior levels, but Fenner, Wilder and several other parents we interviewed denied this, citing its “zero tolerance” policy.

“‘Endemic’ suggests it’s widespread, and I wouldn’t see the students walking past as they are now, happily enjoying their time at the school, if that were the case,” says Fenner. “I’m not saying it doesn’t occur because it does in every school, but what’s important is that it’s dealt with swiftly and appropriately when it does occur.”

Minor disciplinary breaches are dealt with by the quaintly termed “fatigues”, two hours of physical work in the school grounds — often gardening — on Sunday mornings.

“Fagging”, the system in which third formers were effectively servants of their senior-student “fag master”, was phased out in the early 1990s. Third formers are now assigned senior “mentors” but aren’t expected to perform any tasks for them.

Wilder says while the fagging system was undoubtedly abused, “the relationship with many, many fags and their fag master was a very strong one. My first year here I was teaching third-form religious studies and I used to ask what was the best aspect of King’s. A huge percentage put down ‘my fag master’ because he was like a big brother.”

Several older former collegians we spoke to remember their early years at King’s less fondly.

“I wouldn’t have said they were the happiest days of my life, but I would never blame the school for that,” says Stuart Grieve, QC, who attended in the late 1950s. “I just wasn’t enamoured of the place like a lot of old boys are. I was picked on and I probably deserved it. I think I was a little shit.”

He recalls the strict hierarchical system and says today’s King’s is vastly changed. “Those television images of boys with their arms around each other crying and so forth, I would think that wouldn’t have been seen in my years at the school or for some time afterwards.”

Though he didn’t send his older two sons to King’s because “we didn’t want them to be snotty-nosed little gits who had only experienced private schools”, he now has a son from his second marriage who’s at King’s Prep in Remuera and may go on to the college.

The boy was at a state primary school but they transferred him to King’s Prep “because we thought he would get pushed harder academically — and I think actually that’s happening. It’s important to try to instil in them some sort of work ethic as young as you sensibly can while still giving them plenty of time to play.”

Grieve says if he feels his son is a shy and retiring type who couldn’t handle the “rough and tumble of Grammar”, he’ll probably opt for King’s College, which he believes has a more individualised, nurturing environment.

Crown prosecutor Simon Moore, SC, agrees today’s King’s has changed from the place he attended in the 1960s, which was “not a warm place”.

“It suffered from the legacy of the model it tried to emulate — a 1920s English public school. Silly things like cold showers — the concept that a cold shower is a good thing for you in the morning. I mean, for God’s sake. A cold shower consisted of the prefect turning it on and everyone running through it. And the lavatories didn’t have doors on them. Some people loved it. I didn’t.”

He had a younger brother in the same house but the rules of seniority effectively “prevented me from communicating with him and if I did, I got into trouble”.

Moore says he sent his sons there — the youngest left last year — “and they had an absolute ball. The place is enlightened, it educated them superbly, it was sensitive, it introduced girls. Compared to the school in the 1960s, it’s chalk and cheese.”

King’s parents pay a staggering $20 million a year to send their children to the school but Fenner says that with 10 per cent of the roll receiving some sort of financial support, “we do have a reasonable cross-section of society here”.

It costs $11,600 a year to board at the school and $20,000 for tuition, and fee increases have averaged 5.6 per cent a year for the past five years. The school’s fundraising foundation is trying to increase the number of scholarships.

The board of governors chairman, lawyer Peter Ferguson, says they have tried to keep fee increases to a minimum. “We don’t aspire to be the most expensive private school in New Zealand because it’s not a benefit.”

He says up to 80 per cent of new students have no family links with the college, yet many parents believe there is no point in applying without a prior association. The recession has also shrunk the waiting list — this year, for the first time in his 19 years on the board, the school didn’t fill all its Year 9 places.

The huge cost — more than $150,000 for five years of a boarder’s secondary education — leads some parents, such as Trisha Whiting, president of the Friends of King’s College, to tell their sons their schooling is their inheritance.

Like roughly a third of the school’s parents, Whiting lives in the Auckland Grammar zone, but she says she chose King’s mainly because of its smaller roll — less than half Grammar’s 2500. Fenner, like previous headmasters, is said to know each boy by name.

Whiting is also a big fan of the house system, which “encourages competition in a very safe environment. For a lot of kids, if they can’t get into the first cricket or rugby team, the element of competition disappears out of their life. But in the house system, everything is competitive. I think life’s competitive.”

Formerly a merchandise director for the Topshop chain in the UK, Whiting has worked out that boarding costs about $45 a day for each boy, and that’s “good value. We think kids cost that much anyway.”

Her boys “want to succeed, they want to do the best they possibly can in everything they do. I say to my kids, their education is their inheritance. We’ve chosen to spend that money because we think it’s the best investment we can make in them. We’ve given them the start in life we think is best for them and it’s given them a lot of opportunities. What they choose to do with that is really up to them.”

She also likes the fact King’s offers both the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) and the Cambridge exam options.

The stress of parental expectations and the busy school life can take a toll on some boys, however. Warner Wilder says some students are aware of the financial pressure on their parents “so they really don’t want to let them down”.

While King’s has traditionally swelled Auckland’s ranks of law and medical students, Ferguson says a new design technology centre, opened about a year ago, shows how the school is broadening its outlook.

But he acknowledges the three deaths will also force the college to look closely at itself, and he expects a detailed briefing from Fenner at a coming board meeting.

Like the headmaster, he refuses to discuss issues around Michael Treffers’ time in the school or Chris McLachlan’s resignation.

“I consider our pastoral-care programme to be a very strong and effective one. However, events of this nature would cause any responsible board to review existing practices to determine whether or not changes are required.”

King’s Notes

- King’s was founded in 1896 and moved to Otahuhu from Remuera in 1922.

- It has 11 houses, six for boarders and five for day pupils. The houses are Averill, Greenbank, Major, Marsden, Middlemore (boarding girls), Parnell, Peart, School, Selwyn, St John’s and Taylor (day girls). Selwyn House, rebuilt in 2004, is the newest and has no dormitories. Every senior Selwyn student has his own room.

- The school began accepting senior girls in 1980 and now has 130 enrolled — roughly half as day pupils.

- The school motto, “Virtus Pollet”, means “manliness prevails”.