Dec 12, 2021 Politics

Charisma is a gift of the gods. Few have it and it’s impossible to learn or to cultivate. Some think they have it, but it’s like aftershave — it quickly wears thin and evaporates. If, like Tim Shadbolt, you are a politician, it’s a priceless asset, lifting you to great heights and protecting you from the political falls that defeat mere mortals. Shadbolt’s charisma has lasted nearly 60 years and, until quite recently, as he got older, he only got better.

The 1960s were a turbulent time. New Zealand was torn apart by conflict. Riots poured out into the streets with South African rugby tour demonstrations, anti-Vietnam War protests and a general unease about the future. If the 50s were dull and soulless, the 60s kicked us in the arse. We were a country void of a future. We hated anything that was new or visionary. We were plunged into other countries’ battles. We were looking for leadership, seeking solutions that never came. We were as much victims as we were martyrs, and we felt dreadfully and absolutely alone.

Shadbolt and I have had parallel lives. We both became icons of West Auckland: he was the Mayor of Waitematā City from 1983 to 1989 before it amalgamated with Henderson, Glen Eden and New Lynn to form the modern city of Waitākere; I became the second mayor of Waitākere, from 1992, until it merged sadly into the super city in 2010. And, although we had different styles, we believed passionately in what the West was and could be. We both grew up without fathers and forged our own way in politics and in New Zealand society. We both believed in socialism and the working class. We were champions of the underdog, the marginalised, and we cared deeply for our Māori and Pasifika constituents. We have never been afraid of a fight.

Shadbolt and I go back to his radical beginnings as a student activist. A phenomenal speaker, Shadbolt was a magnet on the University of Auckland campus, where he commanded enormous attention. I first got to know him when he was part of the Radical Eight, a splinter group of the university students’ association who dressed in enormous black capes with deep-red linings. They looked like the Inquisition. They were advocates for anyone who had been abused or marginalised on campus. This was a time of drugs — dope, LSD and mescaline. Rake thin and sharply handsome, Tim had a theatrical and political flair, and the Vietnam War protests and union unrest offered him a perfect platform. He was a torch to the gunpowder of New Zealand society.

Much of the student fury about the growing war in Southeast Asia, and the potential for New Zealand’s involvement in it, was fuelled by American intervention in politics in New Zealand. While Shadbolt was rattling the cages on campus, I was taking a different approach. Time magazine was hosting massive monthly dinners for New Zealand businessmen which were nothing more than a marketing exercise for the war, care of Kissinger, LBJ and the CIA. I would take the floor at these dinners and lambast the White House-approved speakers about the war’s hypocrisy and its unnecessary slaughter of thousands using Agent Orange and flamethrowers from helicopters.

Tim and I became friends — colleagues in chaos — and our friendship would last all our lives. Explosions started to become an everyday occurrence. You could get in a car and find a box of dynamite or gelignite (stolen from nearby quarries) in the backseat as the driver smoked cigarettes in the front. Doors and windows were being shattered and a police presence was now regular at council meetings, Town Hall events and the hotels where visiting advocates for the war stayed. For the first time since the 1951 waterfront dispute, the police were armed with batons, and the young cops were as frightened as the protesters. When South Vietnamese Premier Nguyễn Cao Kỳ visited New Zealand in January 1967, the Shadbolt-led protesters got serious — broken skulls, blood on the pavement. It was unbelievably brutal. Two years later, when United States Vice President Spiro Agnew visited, we thought we could mark his visit with the wildest protest New Zealand had ever seen.

On a Friday evening in 1969, 400 protesters gathered outside his hotel, the Intercontinental (now the Pullman), stretching across Princes St waiting for the motorcade. Three hundred young cops, fresh out of training college, were as hyped as the crowd. All hell broke loose. I saw Shadbolt thrashed with batons and kicked to the ground. I went in to try to drag him to safety and was also beaten to the ground under a rain of blows. As we lay, battered and bruised, against the fence of Old Government House, we knew the time had come to really make a difference. We both took weeks to recover. Shadbolt would start the Jumping Sundays protest movement and take over Albert Park once a week in an era when it was illegal to protest outside of council-designated areas. He and his mates would steal buses, drive them to the rotunda and park them in a defiant circle. The police, ever brutal, would make the Sundays a bloodbath. Serious times had arrived.

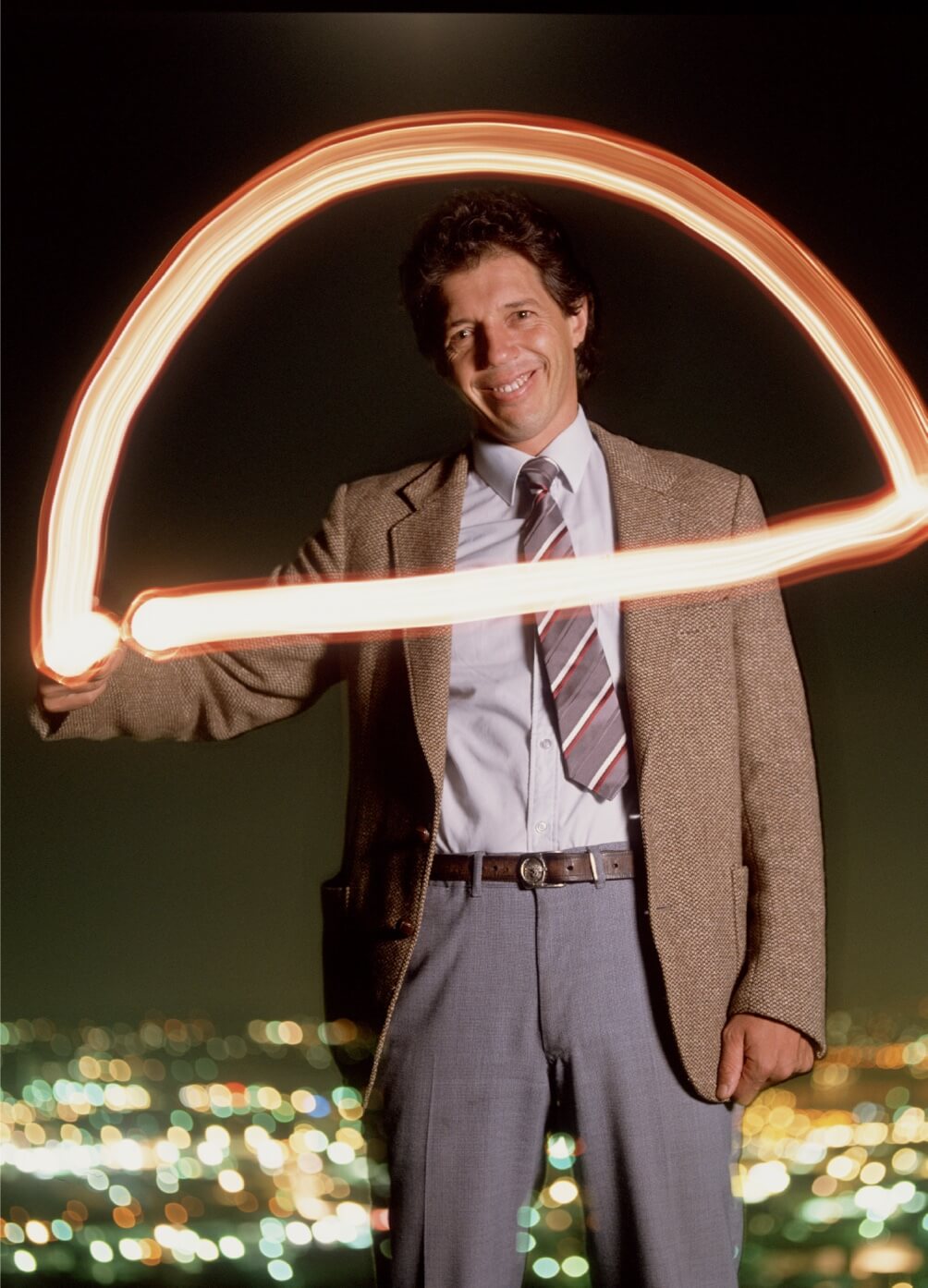

Promoting the Te Atatū dome, 1986, photograph by Ross Land for Metro.

Timothy Richard Shadbolt was born in Remuera in 1947. His grandparents had come to New Zealand and settled on a farmlet in West Auckland, where they survived the Depression with a sustainable garden and small farm. His Dutch mother, Josien Weersma-Shadbolt-Kral, was 18 when she moved to this country. His father, Donald Raymond Shadbolt, was killed in 1952 in a training exercise for the Korean War when his plane crashed into a mountain. His mother moved back to Holland, where Tim quickly learned Dutch. When he returned to New Zealand, he found he had forgotten English. His mother enrolled him with a speech coach who not only retaught him English but also how to speak publicly, a gift that would serve him all his life.

Tim became head prefect at Rutherford High School, where he was a founding student. In May 2021, the school celebrated its 60th anniversary. The day after the reunion, Tim and I sat outside the Hardware Cafe in Titirangi talking about his life. Six kilometres away, he and a group of free-thinking friends had founded the Huia Commune, where sex and drugs were plentiful. They survived two winters at the commune in car-case houses, nothing more than shacks. We drove to Huia, walked up the hill above the store and gazed down on the commune’s remains. Everything was overgrown, a few dilapidated caravans all that remained of Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s Ohu Project dream of alternative-lifestyle communes dotting New Zealand. It was going to be idyllic, the good life.

It was here Tim learnt to pour concrete and build houses. He joined the Hell’s Angels and would ride at weekends as a patched member, but found it didn’t have the kick he’d thought it would. He married his first wife, Miriam, whom he met while living at the commune, and had his first child. In those days, nothing seemed to last for Tim. When, sadly, the marriage ended, he moved to Wellington and began work on a book that would come to define his life, his style and his iconic image. Bullshit & Jellybeans is still a remarkable read. Beautifully crafted, it evokes both the 60s and Shadbolt’s already turbulent life of protest and angst. Tim says he wrote it in six months, and when published by Alister Taylor in December 1971, it was an instant success. Bullshit & Jellybeans covers his imprisonment for giving cheek to society, handing out jellybeans and balloons at council meetings, and committing the then-serious crime of swearing at cops. “Bullshit” is a non-word these days, but back in 1970, it was a punishable offence — Shadbolt was jailed for refusing to pay a fine for uttering it. Taylor later offered Shadbolt a job as co-editor of the New Zealand Whole Earth Catalogue, and Tim went on to write six more books on his life and times.

By 1983, Shadbolt had chalked up 33 arrests, two prison sentences and a grand total of five years on periodic detention. He was starting to like it. He would gather around him radicals, poets and artists, and as his charisma gathered momentum, it drew him to politics. He had a new vision of New Zealand. A new way. His way. He sketched out a political life in the west that would curb development and capitalism — in a way, turning the failed commune of Huia into the city of Waitematā. But first, Tim had to get rid of the incumbent mayor, Tony Covic. In hindsight, Tony was a good man doing what he felt was best for the west. The problem with him was that he was a capitalist, and he had made a number of unpopular deals. He’d also bought a new mayoral Daimler and spent $80,000 on a flash new council building off Lincoln Rd. Tim was up for a fight and he brought it home to Covic, who simply didn’t believe that he could be thrown out of office by a radical loudmouth revolutionary jailbird. Covic was also a tough street fighter. He sued Shadbolt for calling him the “Dally Mafia” at an election meeting. The verdict went against Shadbolt, and he would spend the rest of his life paying off the defamation judgment. But he won the mayoralty in a landslide.

Shadbolt’s win was a sensation. He was a New Zealand hero. He celebrated by leaping on a trampoline for a Cadbury’s ad shouting, “I’ve won! I’ve won!” The remains of the Covic council immediately ganged up on Shadbolt, who says that his first three years were hell. His loyal deputy, the environmentalist and activist Gary Taylor, stood by him and basically ran the show while Tim, who was still broke, continued to run his concrete business and became a successful after-dinner speaker. It didn’t last. Dorothy Wilson, who later became deputy mayor of Waitākere during my own first term as mayor, said Shadbolt was easily distracted by outside influences. He was everywhere — on TV, radio shows, corporate dinner circuits. His plan to build a dome on the Te Atatū Peninsula was a fantastic idea that failed due to his hubris. To secure the project, Shadbolt grabbed the council credit card and, with his family in tow, toured other domes of the world. The cost was horrific. It went nowhere. An enormously expensive video and book on the future dome turned a shaky council into chaos.

At the end of his first term, Shadbolt had made little progress. He was the leader of one of the most dysfunctional councils in the country. It wasn’t helped by the loss of the mayoral chains, which he believes were stolen to embarrass him. While he was short on policy, he had moments of great thinking. He vowed to fell the pine trees on the Cornwallis Peninsula and offer the timber as free firewood to anyone. It was hugely popular, but he didn’t think through the bagging and distribution of the wood, so most of it remained at the end of the motorway in a scrap yard for 20 years.

As his second term ended, Tim was weary and his health and wellbeing were failing. The city was being dismantled in the 1989 reforms that turned Waitematā City into part of Waitākere City. Assid Corban, a cunning politician, knew that the voters who had given Tim a chance were now disillusioned and wouldn’t vote for him again. He was right. Shadbolt was voted out in 1989 and Corban became the first mayor of the new city. As Shadbolt remembers, “one day everyone wants to call me and the next, the phone calls simply stopped”.

Tim in the wilderness is not a great story. He continued to work, making concrete tanks and concreting garages. He did my garage and drive, and they’ve stood the test of time. We would spend hours talking about his next venture. When an opportunity came up, following the death of a Waitākere City councillor, Shadbolt stood for council again. Back in politics, he was a different Tim. A more moderate and focused councillor. Gone were the days of the Progressive Youth Movement; now his knowledge of local government was his greatest asset. He had a shaky relationship with wife Miriam (she would later accuse him of domestic abuse), but they were devoted to their kids. Tim’s Team of allies is now gone; the only survivor is Dorothy Wilson. Taking a long chance, in 1992 Shadbolt stood for the mayoralties of Auckland City, Waitākere City and Dunedin. His slogan, famously, was “I don’t care where, as long as I’m mayor”. He finished third in both the Auckland and Dunedin elections.

I was also standing for the Waitākere mayoralty. I didn’t rate my opponent Assid Corban, whose performances in person were dull and uninspired. But I feared Shadbolt with his wit and charm. He had an encyclopaedia of jail songs and hilarious tales from the trenches. But in practice at the debates, he did little more than tell jokes. The people loved him, but they chose me. I offered Tim the job as Wizard of Waitākere. In hindsight, it was a mistake and I probably would have lived to regret it, but I liked him and he was broke and I thought he would do the job well. He declined it with grace, telling me he had an offer to stand in Invercargill following the untimely death of the legendary mayor Eve Poole. The byelection was held in 1993 and Invercargill found a new, charismatic mayor, whose mission was to make it as famous as he was.

But he still didn’t go into the office often. He toured New Zealand with Gary McCormick and Sam Hunt. I’d go backstage to see him whenever he turned up in West Auckland and we’d laugh about the old days, but he would tell me that he hadn’t been in Invercargill for almost a month. I was a hands-on mayor seven days a week and I have to confess I had a touch of envy. But he took the job for granted. In 1994, he stood as a candidate for New Zealand First in the Selwyn byelection (after Ruth Richardson’s resignation) and lost. Invercargill forgave him at first, and he remained the mayor, but they threw him out in 1995. A term later, in 1998, Shadbolt returned to Southland and was re-elected. He advocated for and built an international airport. No international flights have ever touched down on the runway but he has taken credit for the local polytechnic’s no-fees policy, which will be a lasting legacy. And he sure has lived up to his promise of putting Invercargill on the map. At each election, he’s been returned by huge margins. In 2001, he ran unopposed and in 2010, he defeated the popular singer Suzanne Prentice.

Tim Shadbolt is now in his eighth consecutive term as Invercargill’s mayor and is the second-longest-serving mayor in New Zealand’s history. History (perhaps myth) tells that ancient Celtic druids would select someone from their village and crown him king for one year. The king would have all the power and privilege and pleasures of life, but as spring turned to winter, he would be ritually killed. Though the terms may be longer, this cycle still stands today. We love and adore our leaders, and then we turn against them.

Right now in Invercargill, the city’s beloved Shadbolt, whom the people supported wholeheartedly for 20 years, who put Invercargill on the map, who belonged to them and them alone, is facing his biggest challenge. He’d become a mayoral demigod, the most popular mayor in New Zealand. But the winters in Invercargill are cold and in the past few years, cracks appeared in his leadership. Three deputy mayors either slipped or fell under the council bus. Councillors complained to the Otago Daily Times that their mayor was losing the plot, was vague and forgetful. His running mate and best buddy Nobby Clark, who could see no wrong with the emperor Tim, started to vote against him and was responsible, in Shadbolt’s mind, for the worst betrayal that a mayor could have. He’d entrusted a fellow councillor to sort and store his lifetime of files and personal history, then six months ago, they were loaded in two skips and taken to the local dump. His mayoral office was stripped of his photographs and awards. His council has ignored his absences. The skies are darkening for the Wizard of Was. His credit card has been cancelled. So has his driver’s licence. In November 2020, Shadbolt and his council were the subject of an independent review that found he was struggling to fulfil aspects of his job and that as a result there was a leadership void in the council. Tim objected to its findings and is convinced that the voters of Invercargill will elect him for another term.

On the streets of Invercargill and West Auckland, as I walk and reminisce with Tim, people approach us and embrace him warmly, asking for selfies, to which he readily agrees, posing with that famous toothy grin. His long-term partner, Asha Dutt, plays a major role of minding and managing him. She travels with him and is always close at hand. He is not tech savvy — his new council phone bewilders him and he has been criticised for not spending time in council workshops. In a loopy retaliation, Tim challenged councillors to a running and swimming race. He will be pressed in the months ahead to decide if he will stand in the October 2022 elections. His decision will depend on how his electorate responds. He can leave the political stage and an extraordinary life with dignity and a deep sense of achievement. Or he can battle to retain the mayoralty. The choice rests with him — and Asha.

Tim Shadbolt, 2021, photograph by Victoria Birkinshaw

It’s now mid-August and I’m in Invercargill trying to mediate a deal to save Tim’s personal papers and memorabilia — remnants of a long and extraordinary life — from the local landfill. Tim is glum. A reporter has just told him it’s hanging day down south — his council has met overnight and they are preparing a vote of no confidence, the most damaging action a council can take against a sitting mayor.

Waiting for the meeting, the mayor seems ready to end it all. “What’s next?” I ask him.

He says maybe another book about this daily hell, before telling me he’s getting invitations to stand as a celebrity mayor in other towns that need the Shadbolt touch “to put them on the map”.

Tim Shadbolt — who set a Guinness World Record for the longest television interview, who waltzed on Dancing with the Stars, who starred in That’s Fairly Interesting, who was an extra in Utu and The World’s Fastest Indian, who was New Zealand’s most loved mayor — has finally lost his shine. Charisma doesn’t always last forever. He’s not the Tim I remember from the protests at the Hotel Intercontinental and in Albert Park, the Tim who was hauled away by the police, shouting “bullshit!”. Neither of us is young anymore with our bellies full of fire, ready for the next protest. We are old warhorses and the winters are long and cold.

I ask him if can he do it. Can he let go of the rope?

“No,” he says.

“You don’t care where, as long as you’re mayor?”

He smiles. Silent.

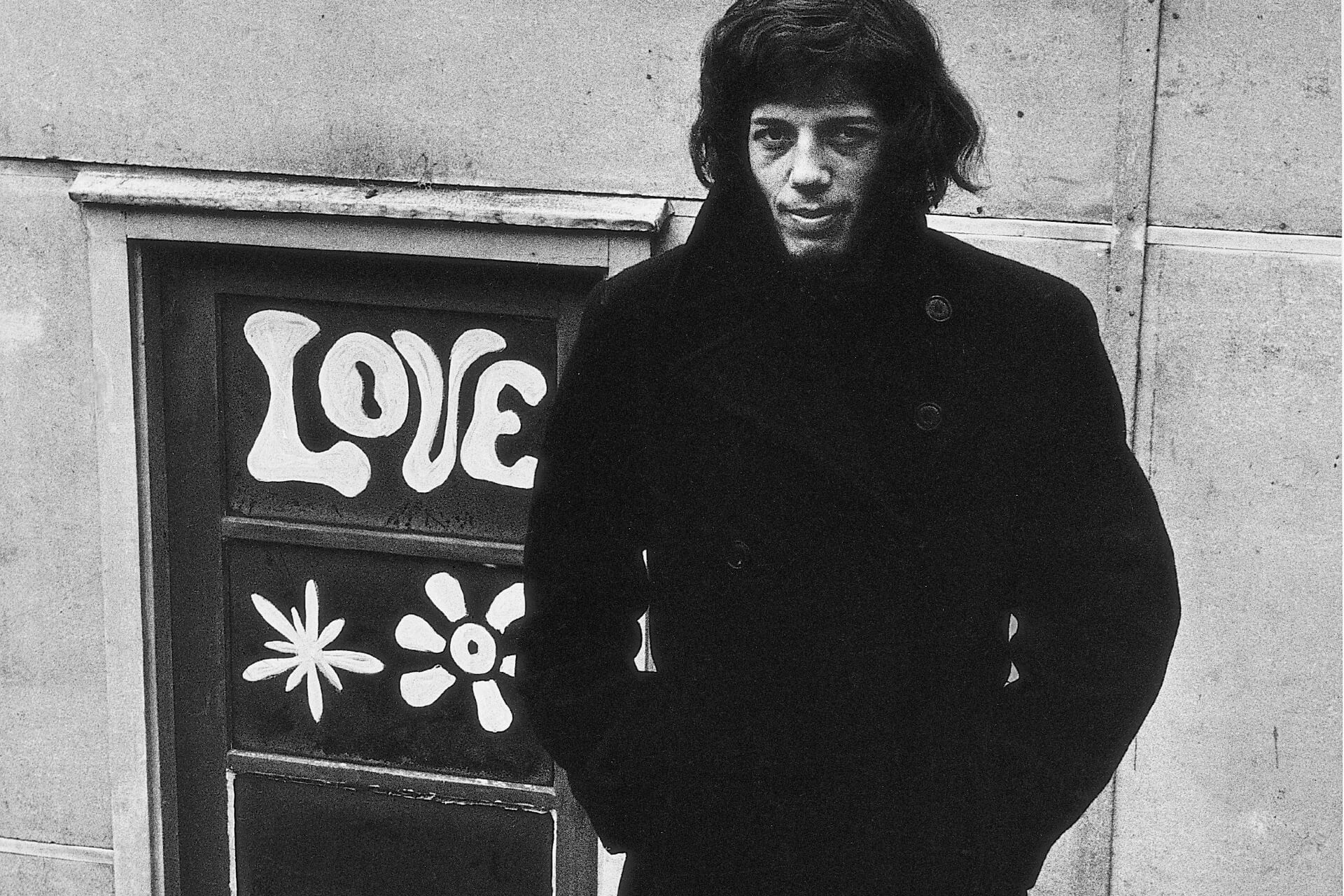

Lead image:

Marti Friedlander, Tim Shadbolt (detail), 1969

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Marti Friedlander, with assistance from the Elise Mourant Bequest, 2001. Courtesy of the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust

—