Apr 15, 2016 Politics

Is Max Key an indulged crown prince or a talented young DJ? Is he a social gadfly, seen at all the right parties, or a powerful new weapon in the arsenal of the National Party? Or all of the above?

This article was first published in the April 2016 issue of Metro.

Spring Break Fiji takes its name from the modern American rite of passage, a celebration of youth and freedom centred on a triumvirate of booze, sex and sand. Young Americans mark their transition to adulthood by flocking to Mexico, where the drinking age is 18, three years below the legal limit in the US.

Until three years ago, whatever New Zealanders in their late teens knew about Spring Break was what they had learned from television — it’s covered off in every youthy TV show whose episode structure spans a calendar year. It’s where Ryan saved Marissa from a prescription drug overdose on The O.C.

Before Spring Break Fiji, the closest we got was “New Year’s”, which happens at the start of peak summer. But in 2013 entrepreneur Rich Henry spotted a gap in the party market and launched Spring Break Fiji — a week of partying after winter but not too close to New Year’s. In 2014 the event sold out. In 2015 it sold out so quickly Henry added another week. That sold out, too. He added a third.

The five-night party takes care of almost everything: flights, transfers, food, accommodation and entertainment.

It makes such a difference. For many people, New Year’s requires an inordinate amount of organisation, including, but not limited to: where are you going? Whose car are you taking? Whose company can you put up with on the eight-hour drive to Gisborne? With Spring Break Fiji, as it says on the website, all you do is: “Just turn up at the airport and be ready for the time of your life.”

This is both an appealing marketing pitch and a practical necessity. It almost certainly wouldn’t happen if people were required to book their own flights and charter their own yachts from the mainland to Beachcomber Island.

Last year, Metro named Max Key as one of the most influential young people in Auckland. He has 28,000 Instagram followers.

The entertainment roster is filled by Auckland disc jockeys, most of whom are associated with Spring Break’s media partner and sponsor GeorgeFM, the MediaWorks-owned radio station where occasionally I do on-air shifts.

Imagine my intrigue, then, when I saw alongside my own name on the 2015 line-up, the name “Troskey”, the portmanteau alias of DJ duo Joshua Troskie and Max Key. The PM’s son has historically been off limits to the media. No one gets close. And now I was going to spend five days on an island with him.

Last year Metro named Max Key one of the most influential young people in Auckland, citing his 28,000 followers on Instagram, his cadre of wealthy and wealthy-looking young friends who flaunt their hip hop-inspired swagger across downtown nightclubs, and his dad.

Yet just a few months later, Metro’s readers had their own say, voting him the second most annoying Aucklander of 2015, behind talking Maserati pamphlet Mike Hosking.

Who is he really, this living, breathing 20-year-old pang in Auckland’s conscience? What’s he like? Can he really DJ? We deride him, sometimes very publicly, but who doesn’t want to know about him?

The Spring Break Fiji audience, just over 200 on each trip, is split down the middle gender-wise, ranges in age from 18 to mid-20s, and is made up mostly of students, recent grads with a new job and a bit of money coming in, and tradies. (Electronic music is fast becoming their music of choice, loosening rock’s 50-year, iron-fisted grip on building-site radio.)

They don’t do drugs, not really. While drugs feature heavily at most five-day raves, you’d be hard-pressed to find them at Spring Break, most likely on account of the sniffer dogs at Auckland and Nadi Airports. Days are spent recovering from last night’s hangover (swimming and lounging on the beach), congregating around the communal eating area (omelettes for breakfast, curry or pasta for lunch, curry and pasta for dinner) and generally getting yourself back into fighting shape via cocktails or beer so you can spend the evening on the sand d-floor dancing to bass-heavy electronic music.

There’s debauchery: what do you expect from young, often single people at a party on a tropical island with a fully stocked bar? But no one has died, although this year there was a fire (the people’s jury blames a cigarette butt) that meant we had to leave the island a couple of hours ahead of schedule.

In December, a few days after we got back, I rang Max and told him I was writing this story. I asked him for an interview.

“Go on the record,” I said. “You can tell your story, I can tell mine, and somewhere the twain shall meet. The story of the summer!”

He was chill. He said he would like to do an interview with me. Then he told me what I expected to hear — that he isn’t allowed to give interviews, because of who his dad is. But, he said, he would run it past his dad and his dad’s “people”.

So it’s yes to uncensored social media, but no to interviews when we become fascinated by him because of the uncensored social media.

I don’t think that ever happened. Max doesn’t do interviews, not with journalists. What’s he going to say? If it’s weird shit, he’ll embarrass his father. If it’s bland shit, he’ll embarrass himself.

Since Spring Break he has, instead, made a few media appearances, to promote the song he released and the radio show he controversially picked up on GeorgeFM.

He’s very driven. He’s also quite shrewd. When I talked to him he could see the value of doing a proper on-the-record interview: good PR for the launch of his single (Forget You). Don’t scoff — isn’t that what John Campbell was also thinking when he broke his silence for an exclusive interview with Metro last year? He had a new show to promote. All part of the game.

I see Max around at DJ gigs and events. He’s a nice enough dude. He’s 20, which is young, an age when you’re mostly defined by how old you are. You are deemed mature enough by society to drive on your own (15 and a half), have sex (16), drink alcohol (18), smoke cigarettes (18), vote (18) and gamble (20), but not so mature that you won’t soon be drinking a metre of beer as fast as you can (21).

Max is polite, quite softly spoken, has prominent white teeth, smiles more than the surprisingly earnest-looking version of himself on Instagram suggests, and asks for clarification when he doesn’t know exactly what you’re talking about. He is, ultimately, 20. Picture yourself at that age.

If Max Key doesn’t do interviews, it’s not because he’s off limits. True, there’s an unofficial but very strong rule in this country that media don’t go after the children of politicians, and that’s fair enough. But, being 20, he is also an adult and, perhaps more to the point, Max does not stay away from media. On the contrary, he’s fiendishly busy — on social media. He posts a lot. Max Key is a public figure because he has turned himself into one.

John Key talked to the Herald about it last year, after Max released a selfie-style GoPro video on YouTube of a trip to Hawaii with his then-girlfriend. “Some people will make the case I should be the censor,” he said, “but on the other side of the coin, I’m Prime Minister but I’m also a father. Most fathers let their kids have social media pages.”

So it’s “yes” to uncensored social media, and “no” to interviews when we become fascinated by him because of the uncensored social media.

There’s a theory here somewhere, so bear with me. New Zealand’s youth are terrifyingly apathetic, as are lots of young voters all over the western world who feel disenfranchised and bored by politics.

And why wouldn’t we be? Globally speaking, we young Kiwis have it pretty good, living in our advanced, technologically connected island paradise, governed by politicians who work hard not to upset anyone too much. There might be lots to be said for that, but one thing it hasn’t done is inspire young people to become politically engaged.

Thirty-seven percent of New Zealanders aged 18–29 didn’t bother showing up to vote in 2014, the largest percentage of voting no-shows across any age group.

And if our middle-of-the-road politics feel lacklustre, who could be surprised? Just take a look at our politicians.

Aside from maybe Labour’s Jacinda Ardern, there really isn’t an MP out there you wouldn’t flake on if your folks texted you to say their friend, “you know, the politician”, was coming over for dinner. One of National’s youngest MPs, Jami-Lee Ross, somehow feels like its oldest.

It’s a vicious cycle, of course. Political parties know the youth don’t turn out strongly on election day, so they focus their time, money and resources where they can get a better return on investment: old(er) people.

The American writer David Foster Wallace was onto this. In his profile of Republican US presidential candidate John McCain, published in Rolling Stone in 2000, Wallace pointed out that it’s in the establishment’s best interests for young voters not to vote, because it increases the power of everyone else: “If I vote and you don’t, my vote counts double.”

If the youth aren’t voting, older voters become more powerful. And older voters are more likely, statistically and historically, to be conservative. To be National Party voters.

National doesn’t care all that much that young voters are not voting, as it’s an epidemic which disproportionately affects the Greens and Labour. That’s not to say National doesn’t want young people who do vote, to vote for them — of course they do; the more votes the better, it’s a popularity contest.

But how do you attract young voters when the fundamental appeal of your party is in fiscal policy and other insanely boring shit?

Well, imagine for a second you’re Sia Aston, National’s chief communications human. You’re a couple of hours deep into a strategy meeting about connecting with the “voting youth” when you realise that your dear leader’s offspring is actually quite handsome. Possibly even cool. Cool? A word so far removed from modern politics that when it’s said aloud it jars, like Voldemort.

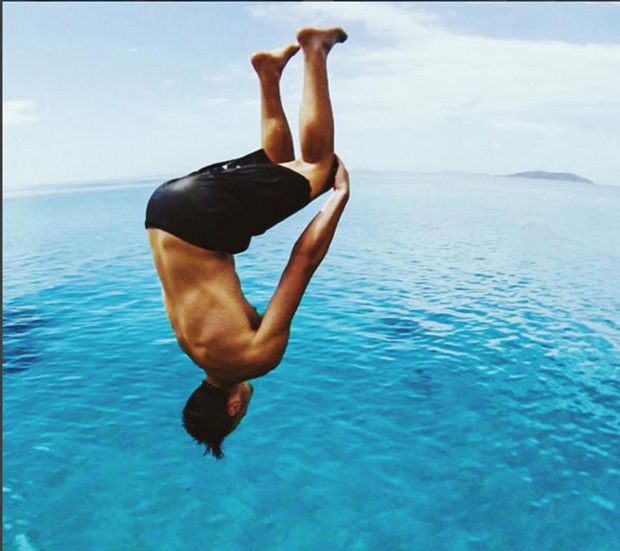

In Max lies a person whose every self-published move — every Instagram snap, Facebook update and tweet — is like liquid gold, dripping success directly into the feeds of his 28,000 followers: tropical islands, first-class flights, good times.

You could never dream up his Instagram in a conservative political focus group. Yet, with apparently effortless ease, it presents exactly the kind of political PR young Kiwis raised on American showiness and hip-hop culture might well respond to.

Yung Pragmatism, bruh.

Is Max the beneficiary of nepotism? Is it, like, John Key is somehow influencing DJ bookings in Auckland’s nightclubs?

Politics that ain’t even politics, ya feel me? Just a perfectly realised and finely filtered picture of National’s “brighter future”.

Now compare that to the shots that sprout up on our politicians’ Facebook pages, Twitter feeds and Insta grids. Contrived photographs with business owners and their confused staff during a day trip to a factory in Thames, polite befuddlement as to why the photo is happening in the first place writ large on their faces, while the politician smiles blandly and consistently. No contest.

Max Key is out of bounds to the media, but his ’gram does all the talking National needs it to.

Aston and her press team might say, “Not true,” and add the lame line that “family is off limits”. But does anyone seriously want to argue there is no cool-by-association benefit to National in the very publicly paraded Insta-lifestyle of this handsome and connected 20-year-old who’s heir to millions? Oh, and the Prime Minister’s son?

Why are we staring? Well, we haven’t really seen this before. The last person who stepped into the public spotlight as their parents’ child was Jaime Ridge, but that was easier to understand because there was a precedent. Her parents, Sally and Matthew, had been doing the spotlight thing (spotlight for the sake of spotlight) for years. For a long time, Sally was right there with her in the photos, for God’s sake.

A prime minister’s kid stepping up to the plate is new for us. So is the wealth. So is Instagram, for that matter. Social media is changing all sorts of rules, although it’s also showing some very old impulses, now writ very large: most of the comments Max gets on his Insta posts are from teenage girls obsessed with attractive, successful people.

“ILY OMG” [I Love You, Oh My God!].

And, “MAX COME TO EPSOM GIRLS GRAMMAR PLEEEEEASE.” With five happy emoticons.

Others aren’t so enamoured, of course: “Stop trying so hard to be the man. You look like an idiot.”

Others aren’t so enamoured, of course: “Stop trying so hard to be the man. You look like an idiot.”

Also, “You couldn’t pay me to listen to the shit that comes out of your mouth.”

And the classic, “Silver spoon up your arse since birth.”

Opinions most likely hardened in our national kiln of tall-poppy resentment.

Max himself got among it when GeorgeFM gave him a regular gig, Key’d In, on Tuesday nights, and he read out some of the comments they’d received. There’s a video of this on the station’s website. “The whole Max Key situation is just plain bullshit,” he reads. And, “Max Key blows goats.” Also, “Shame on you asses for hiring Daddy’s little boy.”

Shame on you asses for letting Max own you, more like.

Daddy’s little boy? Is Max the beneficiary of nepotism? Is it, like, John Key is somehow influencing DJ bookings in Auckland’s nightclubs and on the radio?

We can only wish: imagine the emails from the Prime Minister’s Office inquiring about available DJ slots at such club nights as 1885’s “Molly” (slang for MDMA, the key ingredient in ecstasy) or “The Posse Up” over at Bin Bin Deluxe on the Shore.

Or is it just that the Prime Minister’s son uses his name to help him climb the DJ ladder, get bookings and take opportunities not afforded to normal people? Yes, obviously he does.

And if he wanted to keep the politics away from everything he does, he’d have adopted another name. In his business, people do it all the time.

But DJ-ing, broadcasting, music production, these are careers associated with intangible words like “talented” and “gifted”. They also require a skill set which you can only acquire through hard work and discipline. And they are incredibly public arenas in which to fail. Your audience can love or loathe you on a whim.

Max Key’s name opens doors, but he couldn’t walk through them if he wasn’t talented and hard-working enough in his own right. Will he sustain the advantage he’s been given? It’s up to him.

This feels like just the beginning. None of us — “da haters”, the fans with his Instagram all over their own feeds, the intrigued bystanders and all — will be looking away any time soon. My guess: Max Key will be DJ-ing, or whatever that leads to, very likely still in the public eye, for a long time after Dad has said goodbye to the Beehive.