Apr 4, 2019 Politics

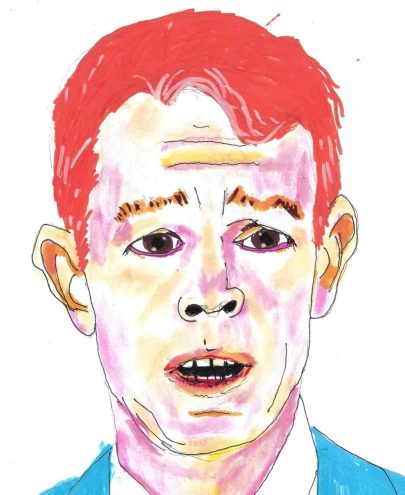

Metro’s political commentator Matthew Hooton discusses why a new blue-green party wouldn’t have the impact on Government some are claiming – and how it would be irrelevant at best for National.

National supporters ought to hope Simon Bridges was being insincere when he described a blue-green party as a “very valuable” addition to the political landscape. Few things could be more helpful to Jacinda Ardern’s increasingly uncertain path to a second term. The blue-green party could only ever get off the ground if huge numbers of National voters switched to the new vehicle, making it at best irrelevant to the right’s electoral prospects. More likely, just enough National voters would switch to deny Bridges or his successor the prime ministership.

Talk about a blue-green party has been around for decades and it has been tried before. The chatter has intensified since elements of the business community failed to encourage the Green Party’s James Shaw to open coalition talks with Bill English’s National after the last election.

Proponents claim there are large numbers of voters, mainly working in the tech or design industries, who care both about the environment and low taxes but for whom National’s brand is just too fusty to ever get a tick. Apparently tempted by Gareth Morgan’s TOP in 2017, most ended up voting for Ardern. In 2020, the theory goes, they might be prepared to back a sufficiently cool and credible ‘blue-green’ alternative, even though they know it has been set up to put National into office. This is startlingly optimistic.

Undeterred, one National MP sympathetic to the proposal believes there could be as many as 1000 such voters in their electorate. Assuming this is correct and can be extrapolated to all other electorates, it would suggest there are around 60,000 potential blue-green voters across the country, roughly the number who voted for TOP.

The problem is that 60,000 voters aren’t even half the number needed to get to MMP’s 5% threshold. To ensure these votes weren’t wasted, a National MP would need to forgo their seat for the new party’s putative leader, Vernon Tava, who secured 0.78% of the Green Party’s popular vote when he stood for male co-leader in 2015 and who failed to reach the last five when he sought National’s nomination for last year’s Northcote by-election.

You might think a good candidate would be Auckland Central, held by National frontbencher Nikki Kaye since 2008. Those promoting the idea think otherwise, pointing out Kaye’s majority over Labour is only 1581. Instead, they suggest Tamaki or Coromandel, held by National backbenchers Simon O’Connor and Scott Simpson by 15,402 and 14,326 respectively. Quite why O’Connor or Simpson would go along with this is not explained.

Another suggestion is Epsom, where Paul Goldsmith would apparently agree to fall on his sword for Tava rather than Act’s David Seymour, with National voters happily complying. What this navel-gazing ignores is what voters nationwide might think of the whole scam. Small parties in New Zealand that have had an independent heritage and ideological basis have done reasonably well. Think Values, Social Credit and the New Zealand Party in the 70s and 80s; and the Alliance, Act, the Greens, New Zealand First, the Maori Party and various Christian constructions subsequently.

In contrast, small parties that have been founded on mere political calculation or have fallen completely under the wing of a major party have flopped. Think Right of Centre, Mauri Pacific and United New Zealand in the 90s; Jim Anderton’s Progressives in the 2000s and Act, United Future and the Maori Party more recently. This is exactly why the last blue-green effort failed so miserably.

In 1996, the doyens of the moderate environmental movement, including Sir Rob Fenwick, Stephen Rainbow, Guy Salmon and Gary Taylor, established their new Progressive Green Party, when the Greens we know today were part of Jim Anderton’s left-wing Alliance. It would be unkind to Tava to compare his mana in the environmental world with this lot. But, despite such strong leadership, plenty of money and this being back when voters were less cynical about new parties, the Progressive Greens won just 5288 votes, a pathetic 0.26% of the total.

Also, while the hand of Murray McCully can be seen behind the 1996 project, it did not suffer from public endorsements by the leader and a former president of the National Party the way the latest effort has been by Bridges and Michelle Boag.

Perhaps most stupid of all are suggestions National should give political space to a new blue-green party by adopting some anti-environmental positions, on the grounds it can never compete with Labour anyway. In fact, National is perfectly competitive with Labour on environmental policy. As RNZ deputy political editor Chris Bramwell has pointed out, the last National Government expanded Kahurangi National Park, set up 11 marine reserves, protected the Ross Sea, built an extensive national network of cycleways, established Predator Free 2050 and banned shark finning. On climate change, Bramwell might also have pointed out that National’s Tim Groser broadly maintained the emissions trading scheme (ETS), excluded Russian Hot Air from the system, established the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases, led Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform, and helped broker the United Nations’ Paris Accord. And Groser’s successor as National’s climate-change czar, Todd Muller, is close to concluding a tripartite climate-change accord with Labour and the Greens.

This record is certainly no worse than that of Helen Clark, who established the ETS only after eight years of floundering around with the “fart tax” and the like, and Ardern, who has so far done nothing meaningful except her ban on oil and gas exploration, which experts calculate will actually increase global carbon emissions.

How on earth could National gain by giving up any of these positions just to help out Tava? In reality, every party must be a green party to be credible in 2020.

The business community’s failed attempt in 2017 to broker a deal between Shaw and English finally forced them to accept what the Green Party and its associated lobby groups have been making clear since the Values Party was established nearly 50 years ago: that the Greens are primarily an anti-capitalist movement rather than a pro-environmental one.

Waikato University’s New Zealand Election Study shows Green voters overwhelmingly identify well to the left of Labour, with only a tiny minority nominating National rather than Labour as their second option. Green voters sincerely believe that capitalism will inevitably cause environmental degradation even if today’s specific problems are addressed within the existing system. Not many, if any, will ever cross the centre line to a blue-green party.

For so-called “moderate environmentalists” who might cross that line from Labour to National, Bridges is much better to set about winning the argument with Labour over which of the two major parties has the better record.

Almost all polls show National continuing to be ahead of Labour. The Greens and New Zealand First are at risk of falling below 5% next year. Bridges’ best shot at the prime ministership is to focus on getting new votes for his own party and keeping well ahead of Labour, rather than playing around shedding some of his existing vote to unproven and extremely unlikely newcomers.

This article was first published in the March – April 2019 issue of Metro.