May 30, 2019 Politics

Last year, Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community was split in two by the Auckland Pride Board’s decision to ban police uniforms in the Pride Parade. Metro looks at what happened in Auckland, and asks what the events tell us about pride, solidarity, and the city’s queer politics in 2019.

It started with Queen Victoria. In 1972, Auckland’s Gay Liberation Movement gathered around her statue in Albert Park, taping messages to her base like “Camp comes out” and “Better blatant than latent”. It was the first action in a new, more forthright demand for gay rights in this country, and visibility was the rallying cry: that gay New Zealanders should be able to come out of the closet without fear of violence, be proud, and, above all, be seen, by New Zealand’s mainstream, heterosexual, predominantly conservative culture.

Which is exactly why the #ourmarch walk in February 2019 started with Queen Victoria, too. This time, the bronze monarch was holding a rainbow flag. The embattled board of Auckland Pride, still navigating the fallout from its decision that police couldn’t march in their regular uniforms in the 2019 Pride Parade (police officers themselves were never banned), had organised a community walk from Albert Park, following the university graduation route, down to Queen St and up to Myers Park. The board’s chair, Cissy Rock, who’d been vilified by many as the architect of Auckland Pride’s downfall, moved through the crowd handing out rainbow flags. The parade itself, with all its sponsors and floats and families lining Ponsonby Rd, originally scheduled for the following Saturday, had been cancelled.

Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community was cleaved in two by the police uniforms decision. For one side, it was an enormous insult and an act of exclusion towards an organisation that had, they claimed, been working hard for years to improve its attitudes towards, and relationships with, queer people.

For the other, though, the request that police ditch their uniforms for a day was a gesture of solidarity: that though things may have improved for some minority groups, there was still a long way to go — particularly when it came to police treatment of Maori, Pacific and transgender communities. New Zealand’s disproportionate prison and police violence statistics, and controversial double-bunking prison policies that put transgender inmates at potential risk, were cited as evidence our law enforcement was far from perfect.

The acrimony within Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community has been extraordinary. Many people who were close to the events — particularly those opposed to the board’s decision — didn’t want to speak for this story, on or off the record. Others who have spoken have often done so with barely concealed anger, or a kind of sad exhaustion. Several board members have given their side of the story, too.

The split was exacerbated by social media, and by a corporate PR panic that saw sponsor after sponsor pull their support for the Pride Parade. Media organisations poured fuel on the fire, too, and it seemed that in the space of just a month — November 5, when the board made its final decision, to December 6, when a no-confidence motion against that same board was defeated — Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community had fallen apart.

“I think there’s a misconception that we were just bored at a meeting one day and made a kneejerk decision to ban the police,” Zakk d’Larté, the Pride Board’s longest-serving current member (first appointed in 2016), says. “It’s almost laughable. They were never banned, which we’ve always reiterated, but that got lost somewhere in the media.”

So what actually happened? The first that most of the public knew about the split was last November, when the board’s decision was made public. But in fact, the lead-up to that decision had been months, and even years, in the making.

And underneath it all were fundamental questions: what are the Pride movement’s politics, and what form should they take, in an era when many rights in New Zealand have already been won? What are the community’s responsibilities to each other in an age of “pinkwashing” and the corporate pursuit of the rainbow dollar? And what does solidarity look like, amid the vicious digital tribalism of social media?

Auckland Pride was born in 2013, the year New Zealand’s marriage equality amendment was passed. It was a celebration of how far things had come for LGBTQI+ communities, and a way for Auckland to present itself as a gay-friendly, liberal place: part of the city’s contemporary rebranding as hip, progressive and cosmopolitan.

Since its forerunner Hero had disappeared from Auckland’s streets in 2001, due to financial struggles, the city had been missing a big, gay celebration. After consultation led by the Gay Auckland Business Association and driven by Auckland Council, Auckland Central MP Nikki Kaye and the Pride Festival steering committee chaired by Gresham Bradley, it became part of Auckland Council’s Major Events Strategy. Major events need major money. And that meant a need for corporate sponsorship, alongside Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development (ATEED) funding.

Bradley argues that the crucial mistake was made when Auckland Pride changed its constitution in 2017 and opened up its membership. With an organisation like Auckland Pride, he says, “you’re essentially running a small business”, and open membership runs the risk that “special-interest” groups take over (which, in the case of the police uniform decision, he firmly believes to be the case).

How, though, I ask him, do you know you’re actually representing the breadth of the LGBTQI+ community without an open membership? “You will always run the risk of being seen to be an exclusive group,” he answers, “unless you have some form of base of advising, where essentially outside the board there’s a larger group of people who are in fact representative in some way of the community, and you make a conscious decision to ensure that that representation does occur.”

And this, he argues, was in place from the start, with advisers from across the LGBTQI+ community being consulted each year. Others spoken to for this story, however, suggest the advisory group, before open membership, was never fully representative. So much of the schism in 2018 and on into this year hinges on exactly this issue: whether Auckland Pride is essentially a business-modelled entity charged with delivering a celebratory festival and parade, or should be a larger — and inevitably messier — organisation that prioritises wide representation and the full breadth of Auckland’s contemporary queer politics.

Auckland Pride has for years grappled with what genuine representation looks like, both on the board and within the parade and festival programming. In the past, there had been charged standoffs, social-media stoushes and allegations of racism between board members. And for some critics, the involvement of takatapui (LGBTQI+ Maori) and queer Pacific people had, in past festivals and parades, been tokenistic at best.

Throughout August and September 2018, the Auckland Pride board ran several hui around the city and on Facebook, and the issue of meaningful representation came up consistently. “The parade down Ponsonby Rd did have transgender people in it, it did have Maori and Pasifika people in it,” Rock, the board’s chair, says. “But it may have been the way those people were in it, the way they were represented or engaged. Our conversations with takatapui were about them saying, ‘We don’t want to just be rolled out to do your kapa haka or do your opening’.”

The question became what authentic involvement in Auckland Pride should look like for those communities.

“I think it’s the same when you look across [an organisation],” Rock says, “and often where the decisions are made, you’re still not seeing the diversity that you might see on the floor in the workforce. So maybe that’s where people were saying, you’ve got a parade, and on the shop floor of the parade you’ve got Pasifika, you’ve got Maori, you’ve got transgender people. You’ve got a fuckload of straight people — and there was quite a big movement to say ‘get the straights out of the parade’ — but when you look at where the decisions are being made, it’s still predominantly — and I include myself in this — a group of white, middle-class people.”

One of the common threads from the hui, the board claimed, was the nature of state involvement in the parade, primarily focused on Police and Corrections. Some of the board’s critics suggest this issue barely came up at all, but d’Larté says that police involvement in Pride has been a consistent discussion point ever since he’s been a board member. So had the involvement of government ministers, like Judith Collins, who’d walked with the police in 2016. As a result, in October, the board ran a “hot-topic hui” about police involvement in the parade, and at that event, People Against Prisons Aotearoa (PAPA) shared statistics about police violence and incarceration rates, particularly against people of colour.

PAPA is a kind of bogeyman for the board’s critics, because their involvement with the Pride Parade in the past has been so controversial. This went back to the organisation’s previous incarnation as No Pride in Prisons, which had disrupted both the 2015 and 2016 parades as a protest against the involvement of Police and Corrections and in particular against the policy of double-bunking in male prisons, which the group argued was leading to sexual violence against transgender inmates.

Some members of the gay community have suggested that the hot-topic hui was actually a smokescreen for a strong anti-police sentiment on the board, and that PAPA had a disproportionate influence on the eventual police uniform decision. Board members spoken to strongly deny this, saying the decision was theirs, taken after the hui — many of which had low turnouts, including from groups who subsequently became some of the most vocal critics of the decision.

At a board meeting on October 23, which was attended by Tracy Phillips, a senior diversity liaison officer from the New Zealand Police, and Gerry Hughes from the Probation Officers team of Corrections, there was robust discussion about what those organisations had been doing to improve their policies, about their potential involvement in the parade, and what form that would take. Then, at a meeting on November 5, the Auckland Pride board voted six to three that Police could participate only if their officers weren’t in their regular uniform. The rationale was that, although the board stood with officers from the rainbow community as individuals, it couldn’t currently stand with the Police as an institution — and that the uniform, as an institutional symbol, made some members of the takatapui, Pacific and transgender communities feel unsafe.

And that was when the real shitstorm began.

This June marks 50 years since the Stonewall riots: the moment when gay and transgender people at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village decided enough was enough and fought back against a police raid on the bar. Stonewall — an action about resisting police discrimination — is widely regarded as the start of the international Pride movement, which now manifests itself around the world in annual parades and marches.

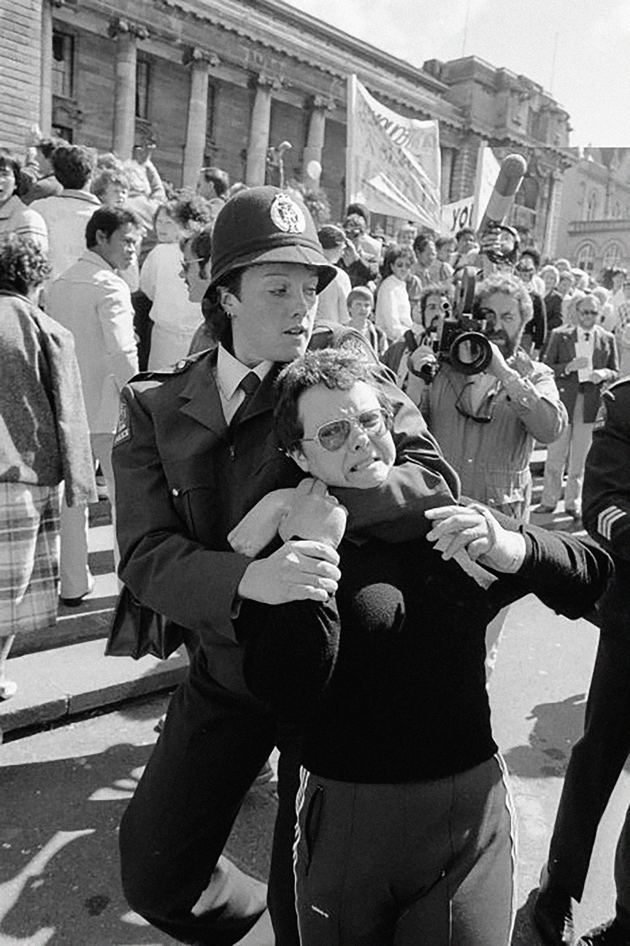

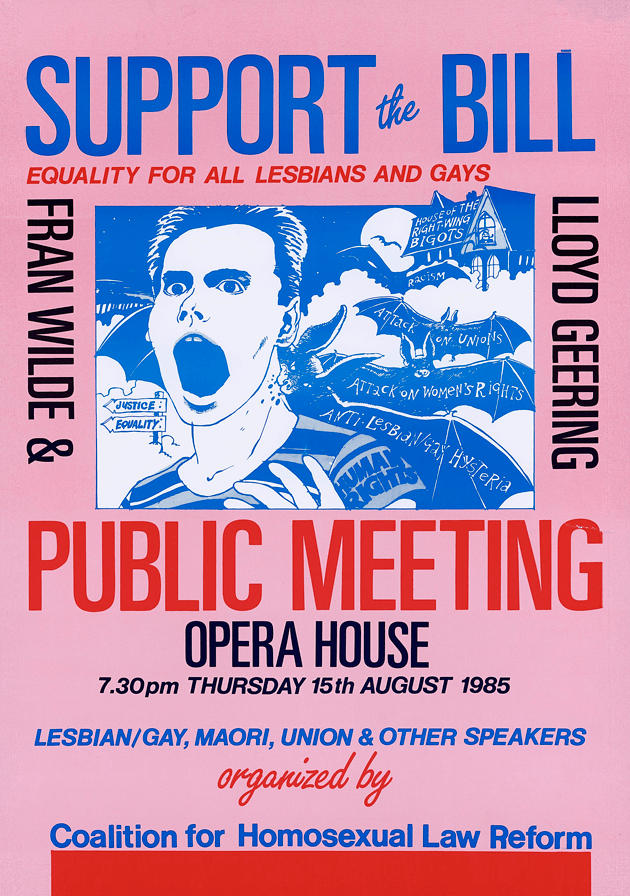

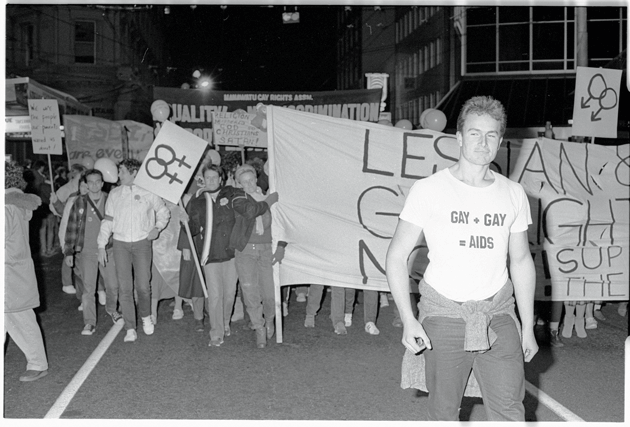

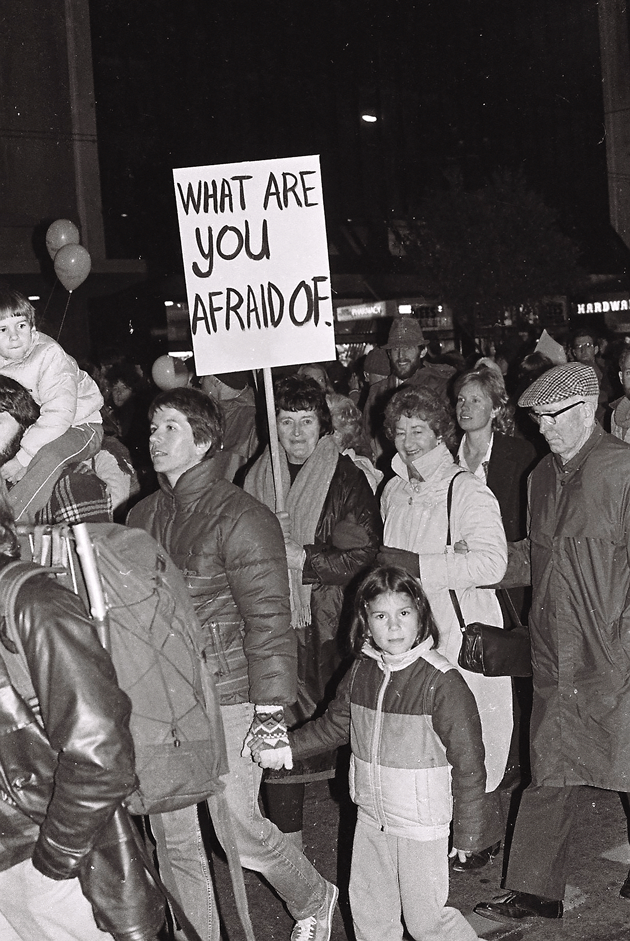

In New Zealand, the Gay Liberation Movement began in the early 70s, but gay communities had to wait until 1986 before the Homosexual Law Reform Act legalised sex between men. The law change came in the midst of the tragedy of the HIV epidemic, which decimated communities of gay men around the world.

Given how late New Zealand was to gay rights, we had a lot of catching up to do. Hero, which ran from 1992 until 2001, became a singular expression of the speed of our transformation, and a commemoration of the lives lost to HIV. During the Hero years there were: changes to the Human Rights Act that banned workplace discrimination based on sexuality, including in the military; Chris Carter’s election as our first openly gay MP (1993); the right for post-op transsexuals to marry as their new sex (1994); Georgina Beyer’s election in Carterton as the world’s first transsexual mayor (1995) and then our first transsexual MP (1999); and the acknowledgement in the census of same-sex couples (1996). In 2004, after Hero had gone, the Civil Union Act gave every New Zealander the right to enter a civil union, no matter their sexual orientation. Auckland Pride emerged in 2013, the year the Marriage Amendment Bill was passed.

Marriage equality was rightly seen here as a major step forward for equal rights under the law. But it is also part of a growing intellectual and political conundrum for LGBTQI+ communities around the world. As more rights are gained, and there is more straight acceptance of them, the challenge becomes how to maintain queerness’s, well, essential queerness: how to ensure that the Pride movement’s activist roots aren’t simply assimilated into a globalised, homogenous, straight-dominated, consumer-driven culture.

The theorist Lisa Duggan calls this danger “homonormativity”: an approach to queer rights that “does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a demobilised gay constituency and a privatised, depoliticised gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption”.

The humorist and critic Fran Lebowitz has been even more scathing about the priorities of gay rights movements in the post-Aids era, particularly gay marriage and equality in the military. “To me, it seems like these are the two most confining institutions on the planet: marriage and the military,” she has said. “Why would you be beating down the doors to get in? Usually a fight for freedom is a fight for freedom. This is like the opposite.”

What both Duggan and Lebowitz are pointing to here is how the granting of rights to LGBTQI+ people has, in the wake of the HIV crisis, largely followed a pattern of normalisation as social regulation. While the straight majority now accepts LGBTQI+ people, there is also an implicit presumption that the gays will play their part: get jobs like us, buy houses like us, watch the same shows as us, eat brunch like us. Meet us, in other words, in our ideal and dreary middle. There is in this, as one prominent member of the gay community pointed out to me, an implicit fear of aberrance — which is one of the possible reasons that trans rights are such a hot-button issue right now, because trans identities are so difficult for a binary, heteronormative culture to absorb.

This fear of aberrance also has some of its roots in the HIV crisis. Stonewall in 1969 was a vital part of a wider sexual liberation movement that grew from the 1967 Summer of Love; a belief that the rights of anyone to their adult sexuality, to their bodies and their erotic selves — especially women in the age of the contraceptive pill — were fundamental to building a humane society. HIV, though, changed the game, and with devastating effect. In the early 1980s, it gave America’s rising conservative right a new stick to beat homosexuals with: a way to tar them with the notion that this was a gay disease contracted through their “deviance” (which also became a way for the Reagan Administration to deny them healthcare and rights).

This is also the danger of the mainstream celebration of gay marriage. It’s very easy for straight audiences to pat themselves on the back and shed a little tear when they see their two good-looking friends getting married in matching suits. Dealing with the pragmatic details of said gay friends actually getting down to the business of fucking each other, not so much. All we really want to know is that they’re ready to settle down.

Fifty years ago, a radical, anti-establishment movement demanded that one of the most fundamental rights of any adult is the right not to be invisible. Now we’re binge-watching reboots of Queer Eye and Will & Grace. So what is it that we’re actually seeing?

It took another few days after the Pride board’s decision for the proverbial to hit the fan. Rock was in touch with Tracy Phillips, and on the evening of November 7, sent her an email, saying: “Our intention is to honour our Rainbow people that are part of the NZ Police and who are proud of their involvement in progressing policy within the Police. However, we do see the Police as an institution and it is the institution that we feel doesn’t meet the degree of safety and awareness of intersectionality that is needed to satisfy the current community feedback.”

By 7pm on November 9, a story on Stuff quoted Phillips as saying she’d made the decision that if police couldn’t march in uniform, they wouldn’t participate in the 2019 parade at all. In the article, Phillips justified this full-and-final decision on the rationale that, because police had marched in uniform previously, to not do so in 2019 would be a backwards step. A police source has told Metro that the decision wasn’t made by Phillips alone, but rather in close collaboration with a core group of diversity liaison officers and their advisers, and that the decision was subsequently supported by Commissioner Mike Bush. The source declined to name the advisers. Phillips declined to be interviewed for this story, saying she was more interested in looking forward to next year’s Pride events. Metro also requested an interview with Bush or an appropriate assistant commissioner who could speak about the police’s decision not to walk in the 2019 parade. The request was declined, and a statement issued, saying: “We are committed to ongoing dialogue and we are working with those involved to address the issues raised by some members of the Rainbow community… While these discussions are ongoing, we are not in a position to comment further at this time, however we may be in the position to provide further comment in the near future.”

Members of the Auckland Pride board met with Bush in March. A press release was expected, but the meeting took place just days before the Christchurch massacre. The police’s staunchness on not taking part in the parade was widely celebrated as a principled stance, and for several months that support held strong. But then a chink emerged in the logic when, for Waitangi Day 2019 — February 6, just three days before #ourmarch — police “dressed down” at the Waitangi commemorations as a way to make Maori feel less intimidated and to make the officers more approachable — the same rationale the Pride board had used in its call about uniforms.

The board’s decision to stand with people of colour who are over-represented in police statistics, rather than to make a decision along strictly rainbow lines, was what really opened the divide in Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community: not necessarily because people disputed the numbers, but because many feel it’s not their fight — that it’s not the job of Pride to try to solve societal issues that extend beyond the edges of sexuality and gender politics.

D’Larté, though, has a different take, based on the fact that the board was actively trying to change how Auckland Pride was perceived by groups who, in the past, felt it hadn’t represented them. “Do we prioritise a blue uniform?” he asks. “Or do we prioritise this hub or core of our people who just want to be heard for the first time and have never had a platform. And that’s where we aligned ourselves.”

Over the fortnight that followed the board’s uniforms decision, the dominant narrative that emerged — supported by state institutions, several corporates, many politicians and large chunks of the media — was that Auckland Pride, as an organisation about inclusion, was going against its values by excluding the police (all the board members spoken to for this story remain adamant that rainbow police officers were never excluded from the parade). Corporate sponsors, including Vodafone, ANZ, BNZ, Westpac, the Ponsonby Business Association, the Rainbow New Zealand Trust and Fletcher Building, dropped like flies.

Most didn’t even bother to communicate their decision to the board directly, issuing press releases instead. “When the times got tough, they went so fast,” d’Larté says. “And I was like, were we really a concern of yours? Did you care for us at all? Not the Pride board, but our community. So that was shocking, really.” But discussions about “pinkwashing” — the process whereby corporations, state institutions and even whole countries seek to improve their public image by presenting themselves as queer-friendly — had started much earlier than the November fallout. Almost immediately after the 2018 Pride Parade, the board had begun to talk about whether the event had become too much of a party for corporates and state organisations like Police and Corrections, who stood to gain from the good vibes and positive PR. The gay kitsch was getting pretty out of control, too: Fletcher’s rainbow mixer-truck, the rainbow-decorated police car, and, most shameless of all, ANZ’s “GayTM”, spitting out twenties from its rainbow maw, all of them with as much sexual-political bite as a Rainbow Care Bear.

There was a sense the event wasn’t queer or political or confrontational enough. A similar issue had started to emerge around the annual Big Gay Out: the one day a year where politicians who don’t otherwise have much to do with LGBTQI+ communities, like John Key and, this year, Simon Bridges, put on pink shirts and pose for endless selfies.

“You have allies,” Rock says. “But your allies are there for you 365 days of the year. And they stand aside when it’s time for the limelight to wash on you. But they also stand up for you when it’s time to show solidarity… That’s what we’re saying about corporates, about political parties, about state institutions. Stay with us, in relationship, for the entire year. Not just when it suits you to be seen.”

Pinkwashing has become a worldwide issue for Pride movements. Israel, for example, has faced criticism for positioning itself as an open, gay-friendly society as a way to score brownie points in the face of its treatment of Palestinians. At a local level, the emergence of Auckland Pride in 2013 can also be seen as a kind of pinkwashing: an acknowledgement, from the upper echelons of Auckland’s political leadership, that a Pride festival and parade are must-haves for any liberal city worth its (rainbow) stripes. At a corporate level, though, it’s even trickier, because, on the face of things, who wouldn’t want our major employers — Vodafone or Spark, for instance, or banks like Westpac and ANZ — to be gay-friendly, and to create internal structures and environments where queer staff can thrive and actively seek promotion without fear of prejudice?

In Auckland, the organisation Rainbow Tick provides expertise to help develop such policies, and its client list is a virtual roll-call of New Zealand corporate life, including many of the companies that pulled out of the 2019 parade. Bradley is a staunch defender of what Rainbow Tick does. “This is one of my big points,” he says, of corporates improving their cultures. “Isn’t this what we want? I keep saying this. The stuff these people are attacking is all the stuff we actually want. But they’re looking at it from an incredibly narrow point of view, and they’re taking it from what I would describe as an extreme-left, union-centric, corporate-business-hating mentality.”

One person’s progress is another’s pinkwashing. This has become a major ideological rift within the LGBTQI+ community — a political division, essentially, of left versus right, with generational undertones. And when it came to what happened to this year’s Pride events, it had a serious, and potentially lasting, impact.

At a tense meeting at the Grey Lynn Community Centre on November 18, Auckland Pride’s secretary,

Michael Lett, was handed a motion of no confidence in the board. This triggered a special general meeting (SGM) of the Auckland Pride membership, which took place on December 6. Meanwhile, at that same Grey Lynn meeting, MP Louisa Wall was recorded saying that she didn’t want any “fucking TERFs” (a reference to “Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists” who oppose gender self-identification) in the 2019 parade: an unwelcome subsidiary media blow-up that put even more attention on the community’s divisions.

In the lead-up to the SGM, Auckland Pride’s membership swelled dramatically. Even the board acknowledges it was unprepared for this, and there have been accusations since that the votes were being stacked. D’Larté was the membership secretary at the time: “Were there lots from our side? Sure,” he says. “Memberships were [also] coming in for rolling us. It’s hard to say about stacking. It felt equal.”

On the night, in a meeting chaired by the neutral arbitrator Mark von Dadelszen, almost 600 votes were cast. The result was 273-325, against the motion. The board remained. It was an implicit, if narrow, endorsement of its stance on the police. Sources close to events suggest that the mistake the board’s opponents made was in the no-confidence motion; that a motion against the specific police decision might have had more chance of passing.

One of the consequences of the failure of the motion was the founding of a new organisation, Rainbow Pride Auckland, which Bradley and some of the signatories to the no-confidence motion are connected to. The impact of this new organisation remains to be seen, but already it’s been the subject of intense online arguments. Its arrival on the scene is also likely to confuse the wider public, and sponsors, if the two organisations push on with separate pride events in 2020.

Two of the most important questions the local ructions posed are: How queer should an event ostensibly for the queer community be? And what does that look like in 2019? There are plenty of people, for instance, who feel that the “Mardi Gras” parade model has had its day; that, as one source said, it’s not enough anymore to build fancy floats and plop a drag queen on top like a Barbie on a wedding cake. The Auckland event is by no means alone in this regard. In a recent New York Times story about Sydney Mardi Gras, grassroots activist organisations criticised the Australian event for its heavy reliance on corporates. Harsher critics of Sydney Mardi Gras suggest it’s basically become a chance for straight families, once a year, to line up and gawk at drag queens and marching boys. Some members of the gay community spoken to for this story, who were spectators at Auckland parades, said they’d felt something similar.

As a result, the board began to discuss how to “requeer” Auckland Pride: how to place queer sexuality front-and-centre again (something Bradley actually agrees with the board about, accepting that things have become too tame). This, again, was part of the feedback the board received from community hui. One possibility was to limit the number of people on each parade float, so that sponsors would have to prioritise their rainbow people (another dividing line: some in the community feel straight allies have a rightful place in the parade; for others, there were simply far too many of them). There were also discussions about getting Pride out from central Auckland — particularly from Ponsonby — into areas like South and West Auckland, to connect with queer communities there.

This has been yet another sore point. Defenders of previous Auckland Prides dispute the assertion that certain groups may have felt marginalised from the central Auckland events, or simply not bothered to engage because they felt there was no space for them within Auckland Pride. But that dismissal overlooks the massive economic transformation of Auckland, and Ponsonby in particular, since the Hero days. Anyone who spent time in and around Ponsonby in the 90s knows just how important it was as a formative space and place of intersection for Auckland’s creative and queer communities. Now, though, it is a suburb of two-million-dollar houses, European cars, and extortionate boutiques. It is getting whiter by the day, but even more than that, it is becoming a potent symbol of Auckland’s economic stratification. With that in mind, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to suggest that queer Maori and Pacific people, too young to remember Ponsonby as anything other than a strip where rich people eat and drink and shop, might not be particularly interested in taking part in a parade there.

But this is also where we return to the central issue of the LGBTQI+ community’s divide: the ways in which institutions of wealth and state power might be alienating, or intimidating, for certain groups. The police-uniforms decision can be argued about until everyone turns blue in the face, but that argument has to at least acknowledge that this “institutional” question was the framework for the board’s decision. And that decision also has to be seen in light of broader global developments over the past few years.

Since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, a number of Pride movements around the world have started to gain a sharper edge, as well as a growing solidarity with other social-media-era movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. Minneapolis’s police, for example, were banned from marching in uniforms at the city’s 2018 Pride parade, the ban coming in solidarity with the killing of Philando Castile, an unarmed black man who was shot by an officer during a routine traffic stop. (Castile’s death became an international cause because his partner, Diamond Reynolds, also in the car, broadcast the immediate aftermath on Facebook Live.) Police in North Carolina were also banned from wearing uniforms in the parade there after feedback from the LGBTQI+ community.

Across Canada from 2017 through to 2019, numerous police departments participated in parades without their uniforms, either voluntarily or because they were specifically asked to do so by Pride organisations: in Edmonton, because the police acknowledged that some marginalised groups, including refugees, found the uniform intimidating; in Vancouver, because the LGBTQI+ community said the uniform made many among them uncomfortable; in Toronto, both because of racial profiling and because police had failed to take seriously alerts from the gay community about a possible serial killer targeting them (in early 2019, a 67-year-old man was convicted of eight murders). In America, too, homophobic attacks in 2017 were at their highest for a decade.

There’s unquestionably (though not exclusively) a generational aspect to these emerging divides, here and overseas, about what Pride’s activism should look like. For many older members of the community — gay men in particular, whose identities and activism were forged from the trauma of the HIV epidemic — there’s a sense that queer millennials have never had it so good. These are the kids who, in New Zealand, will see HIV eradicated; these are the kids who have to worry far less about having the shit kicked out of them, by cops or garden-variety homophobes, just for walking down the street.

“They’ve done so much fighting,” d’Larté says of the older generation, “and no one wants to take that away from them. We want to stand on their shoulders and continue the work they started. Because the fight’s not over. We’re all fighting the same battle of equality. It looks different in 2019, but it’s the same fight from the 80s. We want to support them, and we wanted them to support us, and they haven’t.”

It’s true that queer millennials face less physical danger, both from violence and from HIV. But to suggest they don’t face brutalities or dangers at all is unfair, and, actually, preposterous. And for young queer people of colour, the risks are even more extreme. Because they are digital natives, they’re more aware than anyone that there’s a thin line between the online white supremacy that led to Christchurch and the toxic white masculinity that also manifests as appalling homophobia and transphobia. During the writing of this story, a new international front opened up, which pointed to these intersections between late-capitalism, oppression and pinkwashing. In April, the Sultan of Brunei, one of the world’s richest men, introduced a new law punishing homosexual acts with death by stoning. The Sultan, through the Brunei Investment Agency, is also the owner of some of the world’s most luxurious hotels, which have become the subject of international protests and boycotts.

Attacks and scaremongering by Trump and his supporters about trans rights (the manufactured moral outrages about gender-neutral bathrooms and pronouns, for instance), as well as the homophobic hard-right turns of many European governments, are more examples of the new risks. “And the sad part about that is, where are our gay and lesbian counterparts in this?” says board member Phylesha Brown-Acton, who is fakafifine and works extensively with trans and LGBTQI+ Pacific communities. “They’re at the UN telling all these people that as a result of trans issues being a priority right now, we’re shrinking their spaces and making them invisible. This is exactly the same behaviour here [in New Zealand]. They have no interest in caring about the wellbeing of trans people in this country. They’re more interested in saying, ‘Those people don’t matter. The only thing that we needed to fight for was homosexual law reform and we did that, so what are they complaining about?’”

Brown-Acton also points out that this isn’t a new fight: that trans people have been arguing for rights for years, even while standing alongside other LGBTQI+ groups as they consistently achieved victories and breakthroughs — homosexual law reform, gay marriage and workplace rights. It’s for this reason she’s critical of pioneering figures like Georgina Beyer (who has, in turn, been publicly critical of the Pride board’s police-uniform decision). “You fought for addressing rights at the time,” Brown-Acton says of earlier activists, “but you’ve done nothing for it to be maintained up to this day. And the fact that people continue to think that police behaviour towards rainbow peoples is absolutely perfect — it isn’t. You just need to look at their Code of Conduct’s grounds of discrimination. It’s only based on sexuality, it’s got nothing relevant to gender identity or gender expression. And for trans people, that’s of great importance, because we’re not defined by our sexualities, we’re defined by how we represent ourselves related to our gender identity.”

More often — daily, in fact — the gender self-identification debate plays out, toxically and cruelly, on social media. This has been exacerbated in New Zealand by the proposed changes to the Births, Deaths and Marriages Act allowing trans people to change their birth certificates, which the government had proposed, and then deferred. For many trans activists, the devastation about this wasn’t just because of straight resistance to it, but because there was so much from within the wider LGBTQI+ community, too.

The social-media slanders and shit-slingings, both about the police and gender self-identification, have been incredibly damaging to Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community. Board members, notably Rock, have been subject to some incredible online abuse. Paradoxically, it’s the community’s very diversity that leaves it so at risk, in an era when difference, within minority communities, has gone from a source of debate in the pursuit of shared values, to a vehicle of rampant online tribalism.

After Christchurch, every one of us faces a reckoning. Social media’s dehumanising decimation of civil society is the central crisis of our age, and no matter what we tell ourselves, we are part of the problem: every tweet, every like, every Facebook post and every comment, no matter how virtuous or right or kind we believe ourselves to be, is simultaneously contributing to that, and to the most grotesque profiteering the world has ever seen. But we keep doing it, hour after hour, day after day, because we are addicted. And that addiction is causing blindness; we’re losing our ability to see each other, except as avatars and clichés and stereotypes and figures to hate and vilify.

This crisis is existential, because our ability to see each other is where our empathy resides, and empathy is vital to being a functioning, responsible adult: the recognition that each and every one of us is vulnerable to attack, but that some of us are more vulnerable than most. The second half of the 20th century sure wasn’t perfect, but it was, when taken as a whole, a period in Western democracies of profound gains for equality and minority rights: the civil rights and feminist movements, homosexual law reform, the abolition of death penalties, the winning of abortion rights: all of them about the integrity and control of our bodies, and our right to be seen. Then along came the internet and along came Facebook and Twitter and we lost our collective minds.

For a movement like Pride, based on solidarity, diversity, empathy, visibility and the rights to our sexuality, the effect of the addiction — the way it’s been used to organise, to conspire, to harangue and fume — has been brutal.

Before #ourmarch, the Auckland Pride board had been privately worried that, given the depth of the split in the community, they might struggle to get to the 500 participants they’d need for the police to close down roads on the march route. The idea of having to squeeze along the footpath would have seemed a total defeat. The worry was mislaid; more than 3000 turned up. There was a noticeable presence of teenagers and people in their 20s, and a big gender non-binary contingent. But there were plenty of baby boomers, too: a gay white couple in polos and Rodd & Gunn shorts who looked like they’d just come from a round at Chamberlain Park; the Shady Ladies of Rocky Bay. There were a few bears; trans kids with ludicrously long legs who looked like Manga characters; queer accountants in rainbow suits; and a young emo woman with her super-preppy girlfriend, who looked like they’d been together for about a fortnight and were still in the first thrilling blush of having found each other.

There were a lot of Maori and Pacific people and a big Asian presence: LGBTQI+ Filipino Aucklanders, one holding a sign that read, “If your gay pride does not compel you to protest, what purpose does it serve?”; and China Pride NZ — their slogan: “Proud to be free to love”. There were also several left-leaning political organisations: PAPA, Auckland Peace Action, the Tertiary Education Union, Unite, Socialist Aotearoa, and the Green Party (the only major political party to show up).

Sharon Hawke — herself takatapui and the daughter and niece of the Hawkes who led one of New Zealand’s most transformative protests, Bastion Point — opened proceedings with a karakia directly under Queen Victoria, and made a joke about struggling to keep up when she muddled all the initials — LGBTQI et cetera — that made up the community standing in front of her. But she also said it was their right to be who they were, and to love who they wanted.

“I think things will never be the same,” Rock said, when I asked her later about everything that’s happened. “I’d like to think #ourmarch demonstrated a groundswell of support for the direction the board is heading in: one that’s more around queer-centred politics rather than pure celebration. I think that we need to as a community, and as a society, think about inclusion and diversity and how those two things go hand in hand. “But it has to be done under a power analysis, and I think that’s what has been missing from a lot of the conversation; a real lack of analysing where the power is, and what that means in terms of decision-making.”

It was Hawke, the women of Ngati Whatua Orakei and Pacific women who led the march in its first stages. Several people carried signs that spelled out “NO HATE IN PRIDE” in red tape, over vitriolic Facebook comments from the preceding months. As the march started down Princes St, two police cars began to shut down the roads ahead of it; the only obvious police presence. Initially slow and serious, the mood lifted into one of celebration as the marchers turned down Bowen Ave. The clouds had burned off and cicadas thrummed in the pohutukawa that hang out over the street from Albert Park, the branches framing the hundreds of rainbow and trans flags in the air.

For an hour or so, Auckland’s LGBTQI+ community was visible, in a way it hadn’t been for a long time. No floats, no glitter, no clapping families behind barrier-fences. Just a group of grown-ups, marching together. “I sit back and reflect and think Pride in the future is not going to be overtaken by this glitz and glam that people expect it to be,” Brown-Acton says. She and other board members feel #ourmarch was an important moment for members of the rainbow community who previously hadn’t engaged with Auckland Pride at all.

“They’re invisible and voiceless as a result of this machine that keeps promoting this glamorous view to the rest of New Zealand and the world of what our community is. But when we’re talking about inclusion, who are we talking about inclusion for? And if that is the case, why is no one asking the question — who is missing from that picture?”

?This piece originally appeared in the May-June 2019 issue of Metro magazine.