Apr 2, 2008 etc

Two young blue-sky thinkers snaffled $99,000 — the first Government grant to a local space programme — although no scientist vetted their proposal. Frances Walsh talks to two rocketeers.

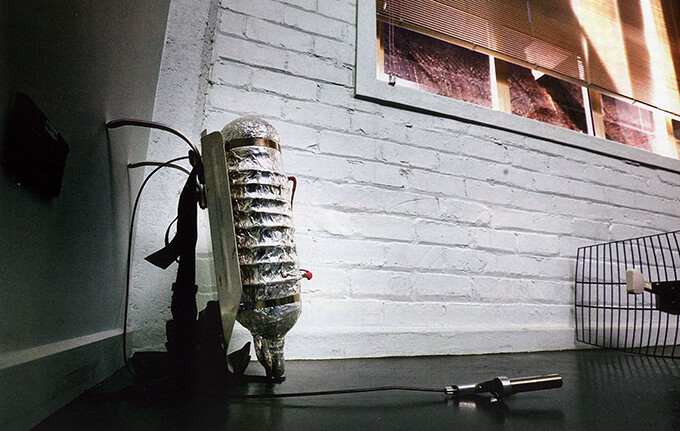

“When you’ve got hydrogen peroxide at 90 per cent it’s highly reactive. When you put a little bit on your skin it turns your skin white and burns and it’s just really nasty stuff. So, at that stage I didn’t have a workshop: I used to use Fisher & Paykel’s workshop because they were so supportive of my rocket career really. So I had a spare bedroom and I converted my spare bedroom to a bubble-reactor-column room until one morning I woke up with a hooer of a headache. Some of the fumes from the bubble reactor had seeped out. Then I bought a garden shed and put a bubble reactor column out in the garden shed.”

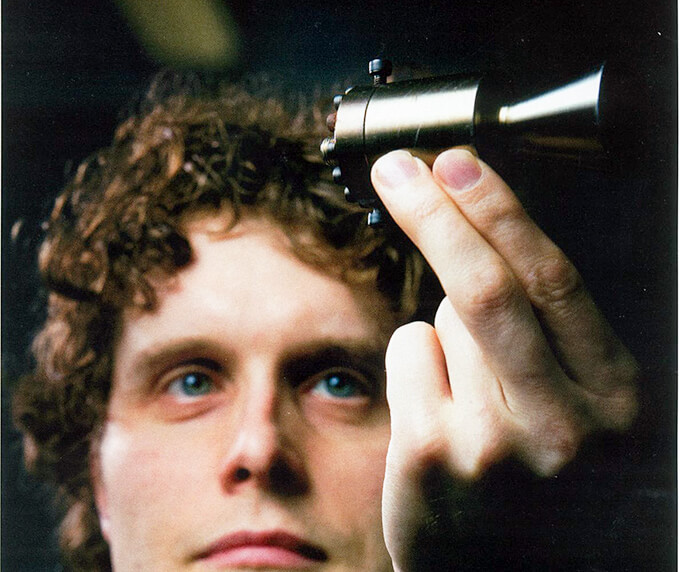

Beck was in the giddy R&D stages of his first-ever rocket engine. These days he’s 30, his ‘r’s still roll and the fruition of the Dunedin lark sits on the shelf of Rocket Lab quarters in Parnell, where he rents space from the Crown institute Industrial Research.

The little engine with a thrust of 20kg is one of several Joe 90 accoutrements on display — all Beck’s handiwork. There’s a rocket-powered scooter (similar in thrust to a rocket-powered bike he rode a few years ago at the Festival of Speed in Dunedin, which delivered 100kg per second); a rocket pack (which he tried out in the Fisher & Paykel carpark while on roller blades: “I just fell over”); a water rocket (with which he once intended to reach an altitude of 2km, and enter the Guinness Book of Records); a rocket engine suitable for a dragster (which delivers acceleration of up to 420km/h in five seconds); and in an adjoining laboratory in a safe, a little bar of solid rocket fuel, made to his recipe of ammonium perchlorate, aluminium, hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene. He’ll be needing 197kg of that for his next rocket.

“This represents three months’ work,” Beck says, tenderly cradling the bendy mouse-grey bar, which is similar to that which NASA uses in its space shuttle solid-fuel boosters, he notes. “I went into it knowing nothing about chemistry and thank God there’s some chemists down the end of the hallway because it looks like nothing but there’s a lot of ingredients in there. Those are the three main ingredients but there’s a whole lot of additives and plasticisers and bonding agents and stuff.”

Disconcertingly, in light of the preceding tale of H202 tinkering, Beck thwacks it on the bench, while wearing plastic gloves on account of its toxicity. “It’s good stuff. It’s stable. It’s not going to detonate on you or anything.”

Before founding Rocket Lab in 2006, Beck holidayed for a few weeks in America, while his wife, an engineer, was working there. He bowled up unannounced to a military base in the Mojave Desert, and was sent packing. He visited Minnesota, and with the first civilian to send a rocket into space, with whom he had been corresponding for some time, was received kindly.

The can-do, imperial spirit washed over him and took hold. “When I came back I said, ‘Right I’m going to start the Atea [“space” in Maori] programme, build suborbital rockets and go into space.’”

The galvanising effect of America aside, Beck had also started to worry he was in danger of blowing his arse into smithereens. “It got to a point where it was just too dangerous for me to be experimenting in a private capacity with that stuff, you-sneeze-and-it-explodes sort of type fuels.”

His company’s tough — some would say Herculean — mission is proclaimed on its website: “To provide innovative low-cost solutions that enable public access to space and develop a space industry within New Zealand.” Private citizens and government wallahs alike have greeted the enterprise with some enthusiasm. Says a John van Raalte in Rocket Lab’s web guest book: “Nasa and the politics behind its programme is slow and dangerously complicated, too many mouths, not enough balls. Typical of New Zealand’s ingenuity and make-up of incredibly clever individuals I can see a company like Rocket Lab going incredibly far with this. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Rocket Lab come up with a new type of engine, or at least a way to levitate objects outside our gravity trap. Let me know if you ever require a subject for a manned mission to Mars, that’s something I’ve always wanted to do.”

The Crown entity the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology awarded Rocket Lab $99,000, for research and development last year, the first time since its establishment in 1990 that a grant has been made to a space-faring project, according to the foundation’s business investment manager Tom McLeod.

Beck airs his science cred on his website, concen-trating on his three-year career at Industrial Research where he worked on smart materials, on composites and superconductors. After he finished his tool and die apprenticeship, he tells Metro, he went into the design office at Fisher & Paykel. Then he worked as a project engineer on a 124ft yacht in New Plymouth. “It drove me absolutely clean insane. Those marine boys are nuts. I just couldn’t handle it. They are just rough as guts. I just couldn’t handle it.”

He was consulting with scientists from Industrial Research over acoustic vibration on the yacht when he spied a job vacancy there. He began taking papers in the New Zealand Certificate in Engineering, but gave it away. He contemplated studying engineering at university, talked to staff at the school, where in the past he had supervised student projects. “They acknowledged that the level of work I had done was PhD level but the reality of it was that in the morning I’d have to go to design 101 class… I thought, ‘Bugger this…’ Don’t get me wrong. I’m sure I’d learn a lot but I’ve got better things to do with my time. I can’t just take three years off to suck eggs.”

The payload — the ideal weight of which would be 25kg, when all the centres of gravity would be optimised — might carry the experiments of local and international scientists, to do with micro-gravity and solar physics and upper atmospheric research, as well as the ashes of dead people, which on their return would be certified as “space travellers”.

If all went according to plan, six Atea-01s would be launched in September 2008. New Zealand was ideally placed to be a space leader in the Southern Hemisphere, it was explained. It was well suited to rocket launching because of its clear airspace and favourable regulatory environment, unburdened as it was by decades of historical bureaucracy. Rocket Lab planned to market its technology, systems and components to the international space industry. A rocket for $US80,000 was a steal.

The then Minister of Economic Development Trevor Mallard gave a speech in which he sutured Beck into our aviation, and agricultural, history. Our aviation industry, he said “could not have got to where it is today without some blue-sky thinkers”. Boom, boom. Like Richard Pearse who achieved powered flight in 1903, the Walsh brothers who built a flying boat in 1914, and Jean Batten who broke aviation records all over the show. Not to mention the feats of topdressers. “Rocket Lab and the people behind it are further examples of such creativeness and spirit,” concluded Mallard.

On the minister’s recent trouble, his thumping a fellow parliamentarian, that is — Beck will not brook any wowser tut-tutting. “He’s actually a really good guy. He had to shuffle quite a few appointments to make sure he was there at our company opening and stuff like that. I’ve got a lot respect for the guy.” Appositely, as far as Beck was concerned, Mallard made no mention of Kaipara internet developer Bruce Simpson, who in 2004 attracted much attention (including from Iranians, Simpson claimed) with his attempt to build a $7000 cruise missile with com-ponents bought off the web. “Look, I don’t want to bag the guy but essentially it was a media stunt.” He was never going to build a cruise missile, says Beck. It’s not as if he was a scientist. “It was actually a pain in the arse because when I was trying to do stuff I got, ‘Oh, you’re that guy building a cruise missile.’ No. I’m not. You know? And when you’re trying to get hazardous liquids and fuels and stuff like that and they think you’re a nutter, or more so of a nutter, it makes life difficult.”

Beck’s business partner was also at the unveiling, having flown in from Christchurch. His name is Mark Rocket. “Mark’s more of a geek than me for sure,” says Beck. Not that he’s unfamiliar with the territory. “I’m into Star Trek, yeah, yeah and all that. Sure.”

Rocket: “I’m not into Star Trek so much. I think Alien is my… I think the gritty realism of it is fantastic whereas some of Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica is a little bit fake, a little bit American. That’s what I’m passionate about. What it’s actually going to be like, not all these babes in skimpy costumes running around like Lieutenant Ohura [who spent most of her time fiddling about with an earpiece on the bridge of the USS Enterprise as seen in the original Star Trek television series 1966-1967]…, more about what it’s actually going to be like to live in space. You know, the whole idea about colonising space and travelling to other solar systems and meeting alien intelligence, it’s a fascinating area. It’s all about the universe we live in. We’re in this little blue orb and there’s the whole big universe out there waiting for us.”

Beck provided Metro with an extract from a Nasa publication on the subject. “When the first Sputnik began beeping back scientific data from outer space in 1957, it seemed that the 12-year reign of the sounding rocket as the chief space research vehicle was over.” Think again. They may be the frumpsters of the space world, in-and-out vehicles which don’t see the big geographical picture, but they are relatively low cost and easy to launch, a large one running at $US200,000 in comparison to multimillion-dollar satellites. Nasa still launches 150 a year.

“Let’s look at some of the market areas,” says Beck, who went with Trade Minister Phil Goff and Rocket on a New Zealand trade mission to Canada last September, putting out the feelers, meeting with university profs and with the Canadian Space Agency (annual budget: $C300 million). A suborbital rocket can exist in micro-gravity (or reduced gravity) for something like six minutes, providing opportunities for some hot-damn research. Crystals grow larger and more uniformly in micro-gravity, thus facilitating analysis by x-ray, useful for the pharmaceutical industry developing new drugs; then there’s biological research, says Beck, “cells splitting and doing all their biological stuff”; some materials can be made only in micro-gravity, like Aerogel — a high-strength, porous silica-based material — potentially good for windows, they say. And like ZBLAN, a heavy metal fluoride glass that may produce fibre optic cables with 100 times greater capacity than today’s silica-based ones.

Then there’s research into solar physics, and the atmosphere, and climate change. At the University of British Columbia, Beck met a scientist who kicked around the idea of a joint Aurora experiment. The scenario: an Aurora Borealis dances the fandango. “Someone in Alaska launches a sounding rocket,” says Beck. “We launch a sounding rocket at the same time. We can track the radiation of the magnetic lines right round the circumference of the earth.” One more thing, Beck says, “A good way to test an instrument before you put it on your expensive orbital vehicle is to stick it in a suborbital rocket.”

There is one company in the United States that Beck rates as serious competition, and it has the jump on Rocket Lab. It’s the Connecticut company Up Aerospace, which has launched twice out of Spaceport America in New Mexico and offers to fly payloads for as little as $US2000. In 2006 their inaugural launch corkscrewed back to earth at 40,000ft, not long after lift-off. In 2007 their launch was successful, although things came a cropper on touchdown. The rocket took up 50 student experiments and some commercial payloads: ashes of dead people (including those of the Star Trek actor James Doolan who played the diligent but prone to hysteria engineer Scotty — “What-about-the-dilithium-crystals-Jim!!!”); personal photographs; two Juventus jerseys. But whereas Up Aerospace uses ex-military missiles, notes Beck, Rocket Lab is DIYing, an approach that will keep costs low and allow for bespoke tailoring. “If you want to do something a bit funny then we can do it,” he says.

As to how much of a market Rocket Lab can potent-ially nab, the American non-profit Space Foundation reported last year that the global space economy is growing dramatically: in 2007 it reached $US220 billion in total revenues, which included both comm-ercial space business and government space budgets. Satellites are the business end of the spectrum (used by the military both as “spies in the sky” and in communications). Satellites and United States Govern-ment space expenditures comprise the two largest segments of the industry at 50 per cent and 28 per cent of total revenues, respectively. Mark Rocket can rattle off Nasa’s budget quick as a flash. “Sixteen billion. Their [the United States] military budget is $439 billion.” Right.

“Have you guys had official talks with Nasa then?” I ask Beck and Rocket. “No. Not official talks, no. We’ve had people talking to people. But at this point we’re not in active discussions,” says Rocket.

An interesting dialogue between Messrs Beck and Rocket…

Are there payloads Rocket Lab wouldn’t carry?

Beck: “Of course… we said right from the beginning if it’s involved in the military we don’t want anything to do with it. The military can be quite a tempting cherry because a lot of money gets poured into it but we’re about science, we’re not about killing people.”

Rocket: “Yeah, I guess the military one is a difficult one and we’ve talked about this at length. Certainly if it involves something that’s going to harm people then were not really interested at all but there are kind of borderline science projects that can be military and government funded and it’s very hard when you say, ‘Oh, this is what I’m going to do’ to always stay, there’s a lot of grey and, ah, so it’s hard to not be involved with the military in any kind of way but certainly we don’t want to be involved with any kind of missile programmes or anything to do with armaments.”

Beck: “No. No weapons.”

Rocket: “I mean, we wouldn’t be interested in winning a Nasa contract to build weapons but if it’s to do with research communications kind of stuff then we’re a bit more open-minded on that… to be clear, we’re not anti-military.

“We certainly respect the rich heritage of our military and the fact that every now and then you have to stand up and fight for what you believe in…”

Just as well really. After visiting the size-of-England Woomera military testing facility in South Australia last year and watching a rocket launch of the not-for-profit Australian Space Research Institute, Beck sees the advantages. It would beat recovering a payload off the coast of New Zealand with a helicopter.

Beck has not given any thought to one ticklish issue, however — that of whistling human remains across the gibber plains and past (hopefully) various sacred sites of the Kokatha people. At this stage Woomera is being considered for test launches only, Beck notes. Not that he and his partner haven’t seriously considered things indigenous before. When they set about naming their first rocket they rejected the ole standbys Saturn, Gemini, X-52, Big Boy, and searched for a uniquely New Zealand handle, lighting on Atea, the Maori word for space after a Googling session. “I actually met with the chairman of Ngai Tahu,” Rocket says. “And he’s a real elder. A Maori elder and a real gentleman. And I sort of ran it by him and said to him, ‘Is this cool? Do you think we’re going to step on anyone’s toes?’ and he said, ‘Go for it. It’s fantastic. I’m really supportive of you guys.’” Who knows, continues Rocket, the next line of rockets may be orbital — and called Waka Atea.

Not unusually for those involved in exploration, Beck exhibits jingoistic tendencies. “This is something for New Zealand,” he says. “We want all New Zealand to be proud.”

The adventures of Mark Rocket…

Rocket (37) made his money on the internet. Plenty of it. After being a self-described under-achiever at school, he journeyed to London at 19. The usual bar work and peregrinations around Europe ensued. Back in Christchurch, in 1998 he started up the web directory New Zealand Tourism Online, selling to the Yellow Pages Group in 2006 — the year the business achieved turnover of $1 million — for the rumoured sum of $10 million.

Besides Rocket Lab he currently owns the companies nzs.com, another web directory, and Avatar, a web developing and marketing company with an associated network of sites including Rocket Spam, Rocket Mailing and Rocket Florist, which copped recent flak from the Consumer’s Institute, in a survey of online florists. The Rocket bouquet ordered in Auckland was light on blooms and bore only a passing resemblance to the bouquet photographed on the website.

When he first requested a meeting with Trevor Mallard to discuss their plans to launch missiles into space, the response, Rocket gauged, was along the lines of “You’re taking the piss.” In the early days of Rocket Lab, when Beck was casting around for a backer, Rocket came to his attention, as he did to his compatriots. He was the first New Zealander, and one of 250 people currently worldwide, to buy a $US200,000 ride on a suborbital space flight with Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, loosely scheduled for 2009. Engineer Burt Rutan designs the Virgin space ships to, among other things, fold their wings before returning to Earth and descend like a badminton shuttlecock. “Mark was all over the news,” says Beck, “and I thought, ‘Well he’s really into space and he’s an entrepreneur. This is like a Bert Rutan/Branson type relationship. He’s the entrepreneur. I’m the engineer. This could be good.’”

Beck emailed Rocket, who hived up to Auckland where Beck gave him a presentation. “It was just like Dragon’s Den. He said, ‘So how much do you need?’ And I said this much. And he said, ‘How much of the company are you willing to sell?’ And I said this much. He says, ‘Right-o,’ and that was that.” Beck sold Rocket 50 per cent of his company.

By which time Beck was aware that Rocket was not the name passed down from his partner’s pater, a Mr Stevens. Rocket changed his name by deed poll eight years ago. “It’s funny how the media always ask about the name,” says Rocket, reddening, and huffing and puffing. “Why not? I mean you’ve got actors and musicians and husbands and wives changing their names all the time. It started out as a fun thing for the internet… and it became an affirmation of the direction I wanted to head in.”

So eager was Rocket that he is one of Virgin Galactic’s “founders” — privileges include hobnobbing with Branson on his private island in the Caribbean, having dinner with him in Los Angeles while attending an International Space Development Conference, scoping Rutan’s rocket factory in the Mojave Desert and a recent two-day space-flight training session at the National Aerospace Training and Research Centre in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, about which he is keeping schtum. “I can’t really talk about it because they, ah, they don’t want the Virgin Galactic people to talk to the media about the training till everyone has actually done it… after you’ve done it you can’t really talk about it.”

Rocket sometimes has coffee with the comparatively loose-lipped Jackie Maw, another Cantabrian and one of the four New Zealanders to buy a Virgin Galactic ticket. She has also just been to Pennsylvania — with five other foreigners including a film director, a hedge fund wholesaler, and IT workers.

Maw was put through her paces on a centrifuge — a machine that rotates and applies centrifugal force to a body. She learnt how to cope with g-forces; familiar to readers who have ever been slapped hard on the face. “What you have to do is push the blood back into your head so you don’t lose, for instance, your eyesight.” Maw will go into a ballot with 100 other founders to see on which of Branson’s first flights she’ll fly. But Rocket will be the first New Zealander to lift off, says head of astronaut sales at Virgin Galactic, London-based Carolyn Wincer. He’s been so enthusiastic, she says — evidence of which is posted on Rocket Lab’s website: “I believe it’s paramount for humankind to establish sustainable long-term colonies in space, which will open up infinite resources and ease human-ity’s burden on planet Earth. Virgin Galactic is playing a key historic role in helping to make this happen. I commend them…”

Beck doesn’t share this particular Rocket enthusiasm but will not specify why not. “I’m not allowed to say. Mark’s told me off for telling people.” Rocket may have attempted to impose the cone of silence after a journalist on the East and Bays Courier last year reported that Beck didn’t want to be a space tourist, quoting him throttling his point home. “I know all the engineering and everything that could go wrong.”

Somewhat surprisingly, when Rocket Lab applied for a grant from the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology no scientist assessed the application. Their application to the foundation, says Beck, did include supporting letters — from the director of Asia Pacific Aerospace Consultants in Sydney, Kirby Ikin; the Geo-spatial Research Centre in Christchurch (a partnership between the University of Canterbury and the University of Nottingham and Canterbury Development Corp-oration); and the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (Niwa).

By the looks of things the scientific market for Rocket Lab’s services may be small. “I was involved with a New Zealand sounding rocket programme over 40 years ago, for probing the stratosphere and above, but that sort of atmospheric physics and meteorology is mostly done these days from satellites, long-term balloon flights, and/or atmospheric radars,” says Grahame Fraser, at the University of Canterbury’s physics and astronomy school.

Physicist and Niwa researcher Greg Bodecker, based at Lauder in Central Otago, leads a team which measures ozone up to 35km above the Earth, using balloon-borne instruments and lasers. Beck’s sounding rocket will soar above 100km, but Bodecker currently doesn’t need the elevation. But who knows in the next five years how research may shift, he says. Some gases are hard to measure looking down from satellites. “There’s nothing quite as valuable as being able to grab some air up there and bring it back down and analyse it even if you are just doing it to validate the satellite measure-ments.”

Rockets would be “extremely useful” if Niwa were to extend its research and its reach into solar terrestrial interaction, for example, looking at how levels of the gases nitrogen dioxide and nitric oxide fluctuate in the stratosphere as a result of solar output, which has relevance for the ozone and climate change. Then you may want to shoot eight rockets up over two years, for somewhere in the region of $20,000 a pop. “I remember when Peter did quote me some numbers, it did not seem out of this world.”

As to the more exotic experiments Beck enumerates above, one professor is sceptical. “Well, it’s entirely feasible to build a rocket; the Chinese invented them in 500BC.” But who wants them? asks Geoff Austin, who works at the University of Auckland’s physics department and is chairman of the Royal Society’s committee on astronomical sciences. “It’s a strange thing for us to be doing as a nuclear-phobic, peace-loving country — to be inventing ballistic missiles, and why is the government paying for it?” Nasa publicity mentions experimentation in micro-gravity too, notes Austin. “They need to put some upfront peaceful things to distract the public from their military intention.”

As to the logistics, while the physics department is interested in fibre optic cables, Austin can’t see how it would be possible to build the materials in a suborbital rocket the size of Atea. “Pharmaceuticals and new materials in micro-gravity are really silly stuff.”

The cost is enormous. “Can you imagine making glass windows for houses in a zero-gravity environment? I mean, bloody glass is expensive enough as it is because apart from anything else to heat silica up to glass-melting temperatures in any significant quantity requires a bloody great furnace. So you’re going to put a furnace in a rocket, melt the glass and when you’re in micro-gravity pour it. You ain’t going to do that in New Zealand. I mean, just think about doing crystal growth, new materials, semi-conductor production in this as compared with the [space] shuttle.”

Large crystals grow slowly in micro-gravity, requiring days or weeks. “Well, I don’t know — it just doesn’t seem likely to me. I didn’t want to stop Burt Munro either but on the other hand Burt Munro did not cost the taxpayer lots of money, did he? I mean, I’m in support of lunatics doing funny things.”

Speaking of which, Rocket Lab has entered into “a handshake deal”, says Beck, with the Houston company Celestis Inc, owned by the company Space Services. Celestis launches human ashes into space in various ways, and for various sums. There’s the suborbital deal, where the ashes are retrieved: one gram for $US495. The orbiting the Earth deal in which the circling lasts anywhere between 10-240 years before ashes, on board a spacecraft, are zapped on re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere, “blazing like a shooting star in final tribute to the passengers aboard” — one gram $US1295. But the top-of-the-line deal sees ashes placed in lunar orbit, or on the surface of the moon: one gram $US12,500.

Celestis used one of Up Aerospace’s rockets last year to dispatch Star Trek’s Scotty and 200 others on a suborbital sojourn. Returning to Earth it went AWOL in the New Mexican desert for two weeks because transmitters attached to the payload parachute fell off. “Scotty’s ashes in failed enterprise” the UK’s Telegraph punned. Perhaps, mindful of the event, Rocket, like a good PR-man, is not over-promising. “As we get closer to launch time we need to shape people’s expectations and say, ‘Well, look, this is the rocket-launching business and we expect out of the first six in a test programme that there could be three of them that don’t work out.’ That’s just the nature of rocketry.”

Ashes aren’t the half of it. For $5000, plus GST, Rocket Lab will send up personal mementoes — a photo, a business card or a sample of hair. What’s with that, then? “You’re asking the wrong person,” Beck says. “The ashes one I can see a little bit more. ’Cause if you want to go to space you spend $20 million and go in a Russian rocket, or $250,000 and go on Bert Rutan’s machine, or wait till you’re dead and go on Rocket Lab for a couple of grand. You still get to space. But it’s just you’re not alive.”

Rocket helps out. After sending ashes suborbital you could then put them on the mantelpiece — “You know, part of Uncle Bob that has been to space.”

Rocket is also in negotiations with Microgravity Enterprises Inc, over in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Last year the company began selling “beverages enriched with space ingredients”, ferried into suborbit by rockets. The New Mexico Business Weekly reported that the company has invested more than $US400,000 in three flights, paying $US50,000 for a payload in its latest launch last June. The resulting products include Comet’s Tail Amber Ale, bottled water called Space²0, and the energy drink Antimatter. “A couple of weeks ago a very high-end boutique on the Champs Elysées in Paris ordered some [Antimatter] so it seems cool over there. That’s kind of interesting isn’t it?” says Linda Strine, Microgravity’s co-founder. “The key for us is the ingredients. Like in the water, it’s the electrolytes that we take up. In the energy drink, it’s the vitamins and those kinds of things that we take up. Then of course for the beer we take the yeast. And that’s what comes back so we can truly say the ingredients have flown in space.”

Strine explains a little more about the electrolytes. “You know how you have sparkling water that you buy, not sparkling, but you have purified water in the bottle, you know or the plastic bottle. There’s usually some things in there, and um, in the water and that’s what we take up into space.” Strine wouldn’t disclose just how much of the Antimatter’s milk thistle, ginkgo biloba and panax ginseng have actually visited space — “I don’t know that we have to get into that” — but she notes, “a little does go a long way.”

Microgravity have twice sent up payloads with Rocket Lab’s competition Up Aerospace. The first rocket lost oomph, prematurely. Strine and her five partners took it on the chin and released a “test ale” made by Kelly’s Brewery in Albuquerque. Other products are in the wind. Moon Dust, for example, or vitamins, which can be dissolved in water. “I just had two of them today,” says Strine.

Meanwhile, five rockets have been ordered by two American firms, Beck reports. His company has branded T-shirts in the pipeline, is looking for additional investors, and has just acquired a provisional patent for a hybrid fuel. As Metro went to press Beck was about to test the second-stage rocket engine. He would have done it sooner, but having exhausted local supplies of the change-linking agent 2-Ethyl-1,3-hexanediol, he had to order in supplies from the United States.

He is also turning his attention to the thermal material which will cover the rocket’s nose. Freud would have a field day. Not just because of the obvious sexual meta-text of men and rocketry and blast-offs. (Surely “To boldly go where no man has gone before” was a reference to Everyman Captain Kirk’s taste for virgins.)

Like Beck, the wonderful Burt Munro came from Invercargill. He set the under-100cc world motorcycle land speed record of 190.07mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, on his Indian Scout motorcycle, which he had heavily modified in a most unorthodox way.

“At the Salt in 1967 we were going like a bomb. Then she got the wobbles just over halfway through the run. To slow her down I sat up. The wind tore my goggles off and the blast forced my eyeballs back into my head — couldn’t see a thing. We were so far off the black line that we missed a steel marker stake by inches. I put her down — a few scratches all round but nothing much else,” Munro told Motorcyle New Zealand in 1973.

Maybe Invercargill is the land of yang.

This story was first published in the April 2008 issue of Metro.