May 31, 2017 etc

For more than a century, a tranquil valley in West Auckland has been home to generations of the Gash family. Plans for a major water-treatment plant put their piece of paradise, and the properties of 100 other people, in peril. Since this article went to print, Watercare has canned the Oratia proposal, opting for a site in Titirangi’s Manuka Road instead.

The family saga first began in these parts more than 100 years ago, and prior to that, just down the road in Prospect Rd, Glen Eden, when Irish immigrant Thomas Gash arrived in New Zealand in the 1840s and, with his wife, Henrietta, grew daffodils and raised nine children.

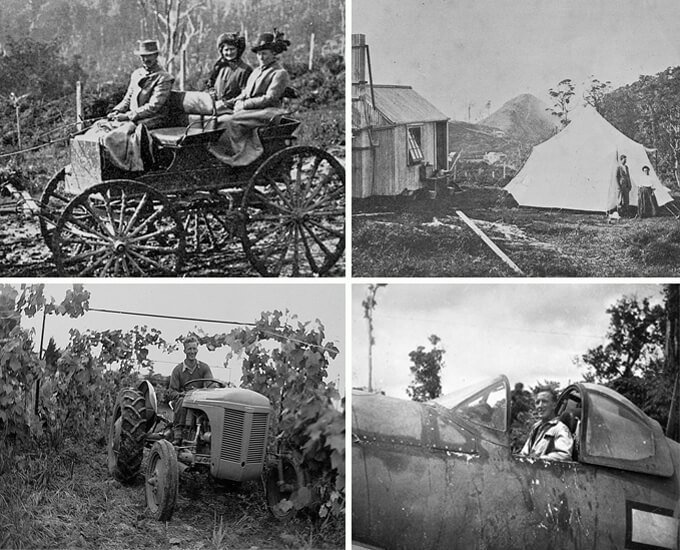

My great-grandparents moved into the Oratia-Waiatarua area in 1905, when the main thoroughfare, West Coast Rd, was nothing more than a dirt track. They lived without power in a tent and a tin shed, with a horse and cart for transport, and my great-grandmother would supplement their income by gathering water ferns from the forest and taking them to the city to sell.

In 1918, my grandfather Edwin Gash left from Parker Rd for World War I. He survived that experience, but when, in 1935, he and my grandmother Mary died within four months of each other, my father and his four siblings, ranging in age from one to 16, were orphaned. The five were to have been spread among various families, but their mother’s sister, the single and gloriously single-minded Dorothy, refused to have them split up and took them into her home in Parker Rd, where she raised them to adulthood.

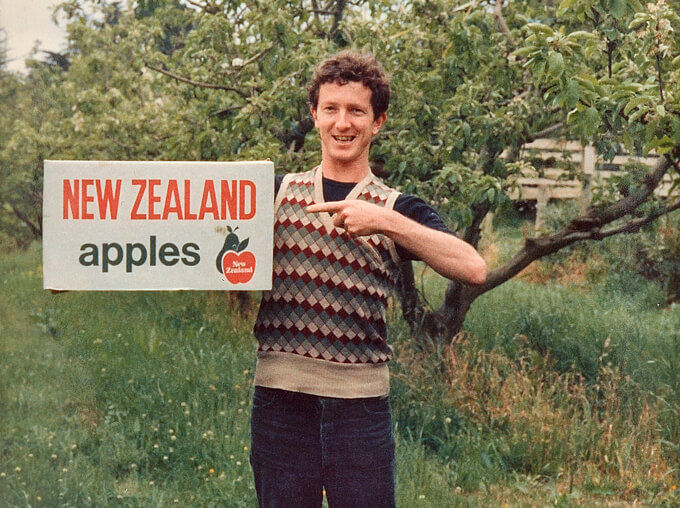

A mere five years later, at the tender age of 19, my father, Russell Gash, became a serving fighter pilot in the Pacific during World War II, then a flight instructor for those following. He, too, survived his wartime experience although, as with so many, he didn’t talk about it often. Upon his return, he raised his family on his orchard in Parker Rd, working hard alongside his younger brother, the other siblings remaining close by for the remainder of their lives. Utilising his pre-war studies in architecture, my father also found time to design more than 70 buildings throughout the district, including the church at the bottom of Parker Rd that is a focal point for the community to this day.

And as for me? My links, built over a lifetime, stretch the length of Parker Rd, right throughout Oratia and beyond, encompassing the West in all its glory, from the savage extravagance of Anawhata, Piha, Karekare and Te Henga to the lush bohemian environs of Waiatarua and Titirangi and the casual but vibrant familiarity of Glen Eden, Henderson and New Lynn. I write songs about it. For a lifetime it has been part of me.

I live in a house that my father and I saved from demolition, broke down and moved ourselves from Waiatarua to Parker Rd back in the 1970s. The sort of project you take on only through sheer ignorance of the impending complexities. It is just a modest cottage really, but at almost 140 years of age, it was the second-oldest building in Waiatarua. It was constructed by the seafaring Captain Peter Theet, and in a neat but somehow unsurprising twist, my cousins in the next road over are the grandchildren of his daughter, who was herself a descendant of Fletcher Christian of Mutiny on the Bounty fame. I have spent the spare moments of my life slowly restoring it back to some sort of glory. It will probably always be a work in progress, a lingering labour of love. Perhaps, now, it won’t exist at all.

This place and its generations of people have been my whole life. As children, my cousins and I traversed its bush and its streams. On a small corner of our family’s original eight hectares, I live alongside my daughter, my son-in-law and my four grandchildren. In the places I ran as a small boy and that I worked in as a young man, we grow fruit trees; we share meals; we give shelter to a single mother and her son. I have for the past 12 years also given shelter to two others, who I first met as small children. This is where I am meant to die.

Some time ago, I realised a 40-year-old dream and began to construct an art and music studio in the barn on my property, with the idea that I would finally have my own creative outlet for my painting and music, after a lifetime of employment and child-rearing. This studio was also to be the vehicle for recording the two albums’ worth of material my old band Waves had recently refined over three years of arrangement and rehearsal time. We are, none of us, of an age where we have years to burn. This was to be, perhaps, a final reward to ourselves as a creative collective.

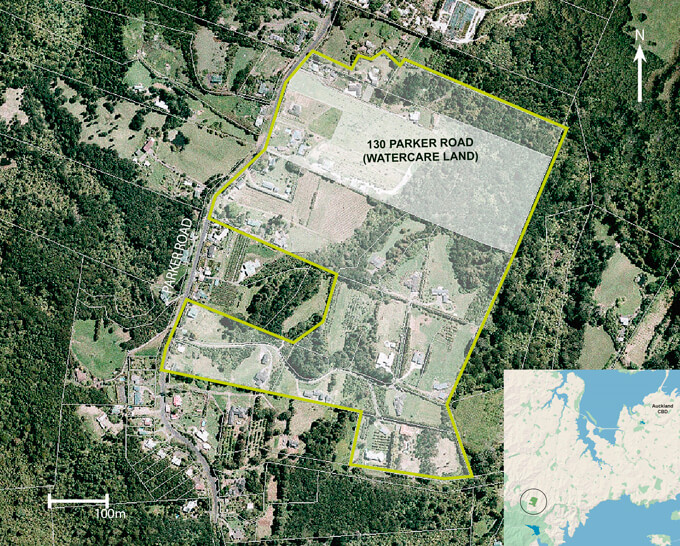

All that stopped dead in its tracks in February, when it emerged that my home, the home of my daughter and grandchildren next door, and those of other families, may be demolished to make way for the new water- treatment plant Watercare intends to build to service Auckland’s mushrooming population growth.

I am angry.

As bureaucrats and politicians play out their games, strategising and jockeying for position around this project, in Oratia ordinary New Zealand families are the casualties. And believe me, it’s been a while since any of them have had a good night’s sleep. Regardless of the outcome, when Watercare makes its final decision on the site for its new plant, the way this process has been handled has already had a profound effect on the psyche of a whole community.

At best, Watercare’s attempts to deal with us have been clumsy, inept and ultimately damaging to a whole cross-section of people — not just those whose homes (and, in some cases, incomes) are threatened, but the many neighbours and, even further out, a vociferous legion of locals incensed at the casual sacrifice of their community and valley to a vast industrial plant.

At worst, these dealings have been cynical and calculating. While Watercare has been working on its agenda for years, we are just ordinary people who suddenly find ourselves propelled into political activism and a crash-course in engineering principles.

My story is only one of many. Just up the road, my friend and bandmate of 40 years, Michael Mason, is also in the zone of destruction. Just down the road, alongside me, live his daughter and his grandchildren. His only son, Nicholas, buried close by in the Oratia cemetery, died in a car accident across from my house. Michael refers to Parker Rd as “a human ecosystem, and an old one at that”. He is not wrong.

Another couple moved into their hand-crafted, rammed-earth eco home just last year, a triumphant moment marking the conclusion of a Grand Designs-worthy building project that was decades in the dreaming and 15 years in the meticulous making. With its soaring stud heights and elegant detail, it is nothing short of glorious. Within weeks, this veritable Renaissance man, Julian Pirie, was being told that Watercare was considering putting a bulldozer through his architectural work of art.

And the last remaining piece of my father’s own footprint, the orchard that took a lifetime of dedicated toil, is set to be swallowed up, taking with it not just the home, but also the livelihood of my stepbrother, Paul Goldsmith, and his young family.

Watercare has seemingly, to date, little desire to understand what a real community is. It is not so convenient for it, perhaps, to engage fully with that concept. To Watercare, we are merely a mark on a map.

Some years ago, I hand-painted the playground and designed the crest for the Oratia District School. It is the school that the children of my great-grandparents attended, that my uncle attended, that I attended, that my children attended and that my grandchildren attend today. That has to mean something, doesn’t it?

This is the community that Watercare’s consultants blithely dismissed with these words: “No significant hurdles or particular limitations have been identified in terms of the environmental, social and cultural criteria at this stage of the evaluation process, although we note a new [water-treatment plant] at this location is likely to cause disruption to the local community.”

We gave them disruption. Perhaps they hadn’t quite read the report, because the scale of the community push-back seemed to take them by surprise.

Within two days of the news of Watercare’s site shortlist reaching our ears, more than 200 people turned out to a community meeting in Parker Rd. Less than a week later, about 700 Oratia residents overflowed the local hall to question Watercare executives, and a week after that, more than 1000 people from the wider West Auckland area turned up to a consultation event that Watercare initiated, then withdrew from.

Support for Oratia is growing. The Waitakere Ranges Protection Society and the Titirangi, Waiatarua and Oratia ratepayers and residents associations are among the many community groups that have backed us, saying that Oratia is last on their list of preferred options.

Why? Because it is so overtly wrong. Because this is a gigantic water-treatment complex, dumped like a giant concrete turd in the middle of a beautiful, historically significant, semi-rural community that has up until now been carefully protected by successive councils.

As Auckland Council has said, “The Waitakere Ranges Heritage Area is 27,700 hectares of public and private land characterised by its exceptional and diverse native landscape, wildlife, heritage sites and Regional Park providing recreational opportunities for all Aucklanders. It is of such national, regional and local significance that the Waitakere Ranges Heritage Area Act was introduced in 2008 to preserve the unique character and natural and cultural heritage of the local area and its communities.”

The act specifically namechecks the valuable role of the semi-rural foothills: “The foothills and coastal areas are a combination of rural, urban and natural landscapes that create an important transition and buffer zone to the forested part of the Ranges.” Our valley teems with plants and wildlife, as does the whole wider area, and there are large areas of covenanted native bush on the proposed Parker Rd site. The Watercare proposal opens up this heritage area to exactly the kind of industrialisation that the legislation was designed to prevent.

The families who forged Oratia in the first place are still here, and they are not the rolling-over type. I will swallow my pride and confess that when I drove through Oratia and up Parker Rd and saw all the handmade signs that people had put outside their gates, I wept. I wept for the fact that this place was forged by people who had one another’s backs.

I rather liked the old Waitakere City. It made me an Arts Laureate. This Supercity could make me an exile.

Watercare decision

On May 30 Watercare announced it would not be using the Oratia site, saying its board had unanimously supported the development of a new plant site at Manuka Road in Titirangi.

Watercare already owns the land, and has planned to lodge an application to the Auckland Council for resource consents later this year, RNZ reported.

The Save Oratia group expressed its relief that Watercare had recognised the extreme social impact that a decision to build in Parker Road would have had.

This is published in the May – June 2017 issue of Metro.

Get Metro delivered to your inbox

/MetromagnzL @Metromagnz @Metromagnz