Jul 1, 2016 etc

Auckland is the “fourth most diverse city in the world”. But what does that mean? Are we getting it more right than wrong, or more wrong than right? Who are we now?

Above: The Lantern Festival in The Domain, 2016. Photo: Cam McLaren. This article was first published in the June 2016 Metro.

Read more: Stories from the world’s fourth most diverse city.

The one culture to unite us all is karaoke. Although, strangely, at the Lantern Festival this year, held in the Domain because the old venue of Albert Park is no longer big enough for the crowds, they were doing karaoke at the band rotunda and the middle-aged men running it didn’t seem to have any idea what

was going on. You don’t see that much: a sound system being operated by the uncoolest dudes in the universe.

Everyone does karaoke, sooner or later, at least once, often quite a lot. And I guess those men were doing their best, despite their incomprehension whenever anyone tried a bit of vocal beatboxing. One young Pacific Island woman gave it a go with “We Should Be Together”, stopped, started, stopped, turned and asked them optimistically, “What’s the key?” It’s possible there wasn’t one. She started again and nailed it anyway.

The lanterns were great. Dragons in the pond, fish in the trees. Paper lanterns with naked flames inside floating up and away. Icebergs, with penguins and polar bears mixed in together, a talking point for parents and kids where one generation lectures the other on how that doesn’t really happen in real life.

And there was a flock of sheep, each with the oddest expression. Some looked like they had a secret it pleased them not to share; others were more belligerent, like they were about to get up on their hind legs and punch you. The lantern makers in Shenzhen or Hong Kong were clearly not familiar with real sheep, but I thought theirs were more appealing.

The Lantern Festival. You go to it for fun. Everyone goes. Young, middle-aged and old, the wealthy and the way less so, Chinese New Zealanders, of course, but also lots and lots of Maori, Pacific Islanders, Pakeha*, Indians, every ethnic group you can think of. Auckland is full of festivals, but only one has a genuinely multicultural audience, and this is it.

And yet, the Lantern Festival is now too big for what it is. There are too many people for the amount of stuff. When it was at Albert Park, you walked in among the trees and the world all around you was filled with lights; this year, to get from one installation to another you had to walk, with the crowds, from here to way over there. It was still great, people still had a lot of fun. But it wasn’t the same. It’s grown out of itself, and it has to find a new way to be. Just like Auckland.

Above: Scenes from the Lantern Festival, photos: Cam McLaren.

Immigration has exploded. In the 12 months to March this year, 124,000 people arrived in New Zealand with plans to stay longer than a year, according to Statistics New Zealand. The net gain nationally, after emigration is factored out, was 67,719. The net gain for Auckland was close to 45,000. It’s as if all of Nelson came to live with us. Only not so white.

Yet more people were leaving than arriving until 2013, when immigration and returning New Zealander numbers both suddenly jumped. The net gain last year was nearly double what the Treasury had forecast.

As David Warburton, head of Auckland Transport, told a conference recently, most Auckland services — transport, housing, schools, utilities and the rest — are funded on the basis of low- to mid-range expectations. But Auckland growth, he said, now “consistently exceeds the high end of projections”.

So who are we becoming? In the 2013 Census, 171,411 people in New Zealand identified as ethnic Chinese — that’s both locally and foreign-born — a jump of 63 per cent from 2001. For Indians, the number was 155,178, up 149 per cent. Filipino numbers, coming off a lower base, rose 264 per cent.

Two-thirds of all ethnic Chinese in New Zealand live in Auckland, as do two-thirds of all the country’s ethnic Pacific Islanders. We also have half of all Middle Easterners, Latin Americans and Africans. In all, 220 ethnicities are represented in the city.

Inside the overall numbers there is also an age skew. As the prominent Taiwanese-born New Zealander, lawyer Mai Chen, says, “Sixty-five and older is the biggest-growing sector of the population, and they’re overwhelmingly Pakeha. But the young are disproportionately brown and yellow.”

In the 2013 Census, 30 per cent of Asians were aged 20 to 34, compared with 18.7 per cent of the total population. A third of international students apply for permanent residency and stay.

What’s the takeout? Chen says, “It’s not ‘us and them’. There is no ‘them’. It’s all ‘us’.” She says whenever she asks groups of mainly white people who’s got at least one Asian in their extended family, nearly everyone sticks up their hand.

Almost 40 per cent of everyone in Auckland was born overseas. That’s 600,000 of us.

Almost 40 per cent of everyone in Auckland was born overseas. That’s 600,000 of us. The city is the fourth most ethnically diverse in the world, according to the World Migration Report, behind Dubai and Brussels, both of which have short-term work-related populations, and Toronto. In just a few years Pakeha will be a minority in Auckland.

It’s worth noting, with these statistics, that many people can, and do, identify with more than one ethnic group, and the trend is growing. The census counts them all.

Are we thriving on the mix, or is that a nice story we comfort ourselves with?

“This is not a conversation about race,” says Chen. “It’s a conversation about the economy.”

That’s a bit problematic, on several fronts. The government’s points system for immigration favours the wealthy, on the basis that they will invest in growth in the New Zealand economy.

But most immigrants looking to invest do what most other economically rational investors do in New Zealand: they buy property. Twenty executives from the gigantic Chinese e-commerce company Alibaba have retired here in recent times. Guess what they’re putting their money into?

Such investors “like being able to buy land”, says Susan Zhu, deputy chair of Auckland Council’s Whau Local Board. “Freehold, with no capital gains tax.”

She says it’s not like Chinese are interested only in property. “Delegations from business and governments arrive in Auckland all the time looking for opportunities. Every month. But we are not good at packaging investment opportunities.”

When overseas investors buy property, the problem is not just that it can drive up prices. Zhu: “It distorts the economy. That’s money that might have been spent more productively.”

There’s no easy fix to this, because who’s going to tolerate a government that might undermine the value of their own property? Nevertheless, more wide-ranging legislation and regulations are required (we’ll return to this in a future issue).

The writer Helene Wong, who has just published a memoir and is perhaps best known as the long-serving film critic at the Listener, adds another note: she says much of the criticism of Chinese in the property market is “hypocritical”.

“We blame the Chinese for driving up prices at auction, but out the back, the sellers are rubbing their hands with glee.” Especially as many of those same sellers have focused their own investments on property.

Next problem: the lack of good jobs. Brett O’Riley, chief executive of the council’s economic development arm, ATEED (Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development), says very bluntly, to anyone who will listen, “We want Auckland to be a high-wage economy.” That, he says, is his agency’s priority.

But tourism is the biggest sector.Tourism is generally low-wage and overseas investment not siphoned off by property looks favourably on tourism-related projects like building hotels.

O’Riley isn’t criticising tourism in itself. On the contrary, it’s surging and he’s excited about it. “Auckland is no longer just the gateway, it’s a major tourist destination in its own right. Airport numbers in the midwinter low this year are expected to be greater than the summer high of just two years ago.”

The boom is Chinese. Auckland Airport, he says, now has 51 flights a week to China, rising to 70 by year’s end, up from a mere 14 just eight years ago.

Despite that, O’Riley wants to attract investors with growth in manufacturing and the tech sector, and Zhu agrees. “We need investment opportunities that create real, high-wage jobs, in internet technology, medicine, food science, all those things,” she says.

When that happens, the material value of immigration will become much more self-evident. “And we have to lead it,” says O’Riley. When he says we, he means Auckland Council. In mid-May, they were trying to do just that, among other things, with a major tripartite conference involving Auckland’s sister cities Guangzhou and Los Angeles.

At the other end of the economy, every other day, or so it seems, a small business gets robbed. With violence. Is there a more beleaguered — or braver — group in Auckland right now than the people who run dairies? Families, earning very, very little.

Why don’t we treat this as a social crisis? Don’t we want corner shops any more? Or don’t we care about their owners?

Here’s a thought experiment: what if most dairies were run, not by Indians, but by middle-class white Aucklanders? Do you think for a second the conditions that allow thugs to attack them so often would be allowed to continue? If the violent robberies in dairies spread to the boutiques of Ponsonby, all hell would break loose, wouldn’t it?

If the violent robberies in dairies spread to the boutiques of Ponsonby, all hell would break loose.

If you want to know what it’s like to be a different race from your own in Auckland, that’s one place to start.

Another is with the bashings of Asian students. One Tuesday in March, two young Chinese women were attacked in Albert Park. The next night, two young Japanese women in Myers Park were attacked, and then, at 9.30 the following morning, a young Chinese man was beaten up on the Oakley Creek pathway near Unitec. The next Monday, an international student was attacked on Khyber Pass Rd. Some of the bashings were severe and all of the victims were robbed: phones, laptops, bank cards, bus passes.

The police have arrested two bunches of kids, aged between 12 and 15. It’s possible it’s isolated: no further bashings have been reported. But it happened.

In the dairies, all the robbers are usually after is cigarettes, some food and a bit of cash. The phones and cards stolen from the students got used straight away on spending sprees.

You can argue that some people are bad and they’ll do it anyway. You can argue that many or even most teenagers have impulses that lead to delinquency, especially when there’s peer pressure. But whatever you think about all that, two other things seem obvious.

One is that people who believe they have no meaningful stake in society will hardly care about its rules. The other is that the belief it’s okay to attack Asians is part of something much bigger. Violence by a few is the sharp extreme of casual, petty, thoughtless, uncomprehending, everyday racism by many.

It’s not just vulnerable-looking students. Mai Chen says, “I’m sick of being pushed over in the mall.”

We were sitting in the boardroom of her law practice when she told me that. Perched above the city with sweeping harbour views, all very corporate. I wasn’t sure what to say. What?

“My husband [who is Pakeha] will turn around and I’ll be lying there on the ground. He says, ‘What are you doing down there?’ I tell him, ‘I got pushed over.’ He says, ‘You don’t think it might have been an accident?’ I say, ‘It wasn’t an accident. They came right at me. I watched them while they did it.’ I don’t like being shouted at in the car, either. Sworn at in the street. And I’m sick of how we don’t talk about it.”

I asked Helene Wong if she thought things were getting better and she said, “I really don’t know.” Wong, who has worked for the government as a high-level policy adviser and board member, said she might feel differently about it “when I haven’t been shouted at for a while”. In the street, she means.

What’s striking, talking to Wong and Chen, is that they have both realised something about themselves: they’re tired of dealing with all this. They’ve spent decades, in their different ways, working hard to help build a better New Zealand. But it’s still the same old stuff. They’re tired, and they’re angry.

Sometimes it’s extreme, sometimes mild but still telling. Chen tells a story of how, for her 30th wedding anniversary, four separate friends, all of whom she loved dearly, gave her white flowers. To her the flowers symbolise death, and she got her husband to take them away.

She also talks about her first visit to her husband’s family home, all those years ago. “It was like having a magical mystery tour. There was raw cheese! I didn’t know you could eat cheese without cooking it.” She says she found it hard to get to know the family because they had “such English reserve”. It confused her; she was used to families “where everyone speaks their mind”.

I haven’t asked the husband if he, in turn, found her family inscrutable.

Multiculturalism, in the sense of ethnically mixed group activities, comes to Auckland in fewer ways than you might expect. Precisely because we have such large ethnic groups, we do most of our big cultural events by sticking with our own.

Upwards of 100,000 people attend the Pasifika Festival in February, but they’re nearly all Pacific Islanders. According to a report commissioned for Auckland Council, there were 472,000 boats in Auckland in 2010, but the people out on the water on Anniversary Weekend in January, and those watching from the shore, were overwhelmingly Pakeha. Diwali enlivens the city every October and its participants are almost entirely Indian.

We regard other tribal activity as not for us, so we stay away, even when the organisers work hard to draw us in. The Auckland Arts Festival and Auckland Writers Festival both have a deep commitment to diversity in their programmes, but they play to very Pakeha audiences. Sitting in the Aotea Centre is something white people do.

But then, I’ve sat in the Maori-run theatre Te Pou, in New Lynn, watching a show entirely conceived and presented by Maori, and still the audience was mostly Pakeha. “Theatre”, it seems, is perceived as something white people do, even though that’s demonstrably untrue among its practitioners: Auckland theatre hums with the energy of Maori, Samoan, Indian, Chinese and other ethnicities.

There are some exceptions. The Lantern Festival, for one. Almost alone among the city’s cultural events and shows, it attracts everybody. Why is that? It can’t be because of the religious and astrological belief systems it’s derived from: its broad appeal surely puts it closer to Santa Claus than the birth of Jesus. The lights at dusk are inherently appealing, even without any symbolism. And it’s a celebration of family, which makes it a real thing.

The music scene is both integrated and not. There’s great enthusiasm for rap from all over, as Leilani Momoisea says (page 59), but the people who go to K-pop clubs are not the people who love their alt-country. It’d take a whole separate story to pick all that apart.

Diwali is probably too much a religious ceremony to attract non-Indians, but India also has a Holi Festival, in which spring is welcomed with everyone throwing coloured powder dyes at each other. “Festivals of Colour” now take place all over the world, with several in Auckland. Some are genuine Holi festivals; others are just a bunch of people having fun. Sometimes, Indians are not even involved. Holi is being appropriated and stripped of its meaning, like Halloween and Guy Fawkes. Mind you, it’s safer than fireworks.

The other culture that unites us is rugby. But even rugby is not the great integrator you might expect. At primary-school level, Maori are more likely to play league and white kids play football. It’s Samoans and Tongans who play rugby.

Even rugby is not the great integrator you might expect.

Besides, Auckland rugby is on the decline. The number of teenage players in the city shrank by 29 per cent during the years 2012-2014, according to the New Zealand Secondary Schools Sports Council. That’s a staggering proportion. In other parts of the country the trend is up, but rugby officials fear that Auckland, rather than being an outlier, is simply a portent of what’s to come.

Rugby factors into our ethnic mix in other ways. Attend any school game in the top grade, 1A, and you’ll see teams almost entirely made up of super-skilled brown players (often brought in on scholarships), with the playing fields lined by flocks of middle-aged white people who’ve come to watch. It’s an odd sight, especially when the game involves the likes of Auckland Grammar, King’s and St Kentigern, which have relatively few brown students.

King’s College, for example, with a roll of fewer than 1000, is about 80 per cent Pakeha and 4 per cent Maori, according to the most recent report of the Education Review office. Their PI student numbers are so small they’re not recorded at all. That means there are around 40 Maori kids at the school. With a largely brown 1st XV, it’s reasonable to assume almost every Maori boy at King’s is playing rugby.

In schools as in sport, the ethnic basis to who does what with whom is a symptom of a much bigger issue for the city. Many ethnic groups are now big enough for the people inside them to stay inside them. This is what white people have always done, of course, even while eyeing with suspicion any other ethnic group doing the same.

Many ethnic groups are now big enough for the people inside them to stay inside them.

In Wellington, a school with 20 per cent non-white students counts as a multicultural school. And that 20 per cent will probably have a long tail of different ethnicities, each with perhaps just a family or two in it, which forces the kids into ethnically integrated friendship groups.

In Auckland, a school with 20 per cent non-whites is about as monocultural as they come. That’s King’s College, and Orewa College on the Hibiscus Coast. St Cuthbert’s and Rangitoto College are much more typical among high-decile schools: they have only around 50 per cent white students. Auckland Grammar has less than that. In most of these schools, it’s Chinese, Korean, Indian and other Asian students who have made the big inroads, and usually in groups.

Mai Chen says when she arrived in New Zealand as a six-year-old, in 1970, no one in her family of seven knew any English and there were no other Taiwanese families around. “We knew nothing. We had to integrate fast, just to survive.” If her family arrived today, she says, they’d probably remain within the New Zealand Taiwanese community.

In the west and south, it’s Maori and Pacific Island numbers that dominate. At decile 1 McAuley High School in Otahuhu, where their pass rates would reflect well on most decile 7 schools, half the roll is Samoan. Pakeha make up less than 1 per cent. (We’ll be looking at quality in Auckland secondary schools in detail, next issue.)

Every school I’ve been into in this city — and that’s a lot — works hard to promote the values of a multicultural society: respect, tolerance, learning how to enjoy diversity and spot the opportunities it provides, and also, importantly, pride in one’s own cultural identify.

Ironically, that pride also feeds behaviours that are less beneficial. Kids form gangs; there’s bullying, especially of those who are different; there’s a sense of superiority, a willingness to believe harmful stereotypes and propagate them.

It’s true everywhere. Maori kids and Asian kids have just as many stories about Pakeha superiority and bullying as Pakeha kids do about that threatening clump of brown kids waiting on the corner.

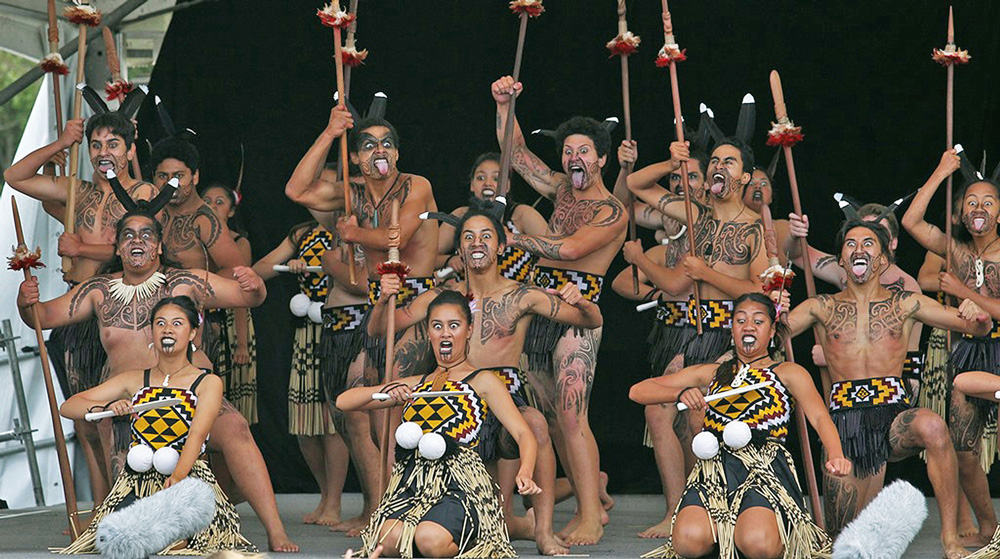

Friday was VIP day at ASB Polyfest, the cultural jamboree for schools that has grown from a four-school competition in 1976 to become the largest gathering of Maori and Pacific Islanders in the world. Maori are at its heart, but the Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islander and Niuean stages were pumping too, and the diversity stage, hosted by Botany Downs Secondary College, also went off. For four days, the roads around the Manukau Sports Bowl were clogged right up.

The dignitaries assembled in the VIP lounge, with the Prime Minister, John Key, front and centre. The Baradene College Tongans came out to perform: five dancers and a big group of singers. The dancers were serenely poised, beautifully costumed, each with a single plume towering above her head, and the group’s dancing was spare and elegant. Afterwards, behind the screen at the back of the stage, they erupted in squeals of excitement.

Toisulu Brown, mother of former All Black Olo Brown and a powerhouse at Auckland Girls Grammar, handed out lei and proceeded to tell the PM, publicly and extremely bluntly, that they needed more money.

Key had a great time. He told the VIPs, “My knees are in great condition,” and did that crossed hands and knees jokey dance thing. He spoke to the phones, all held up to video him. Tupou Manapori, known to all as Mama Tupou, from the Cooks stage, told him, “Next year, we will definitely get you up on stage, in costume.” He shot back: “I can’t wait.”

This was the third year in a row Key has attended Polyfest. He is the only sitting PM ever to have been.

Theresa Howard, the event director, says Polyfest gives the kids far more than performance skills. She lists discipline, leadership, strong work habits, respect. I’d add, for at least some of them, grace.

Theresa Howard, the event director, says Polyfest gives the kids far more than performance skills. She lists discipline, leadership, strong work habits, respect. I’d add, for at least some of them, grace.

In Tongan performance, as in some other Pacific cultures, there is a little head flick to the side, usually done with a cheeky grin, as if the dancer is saying, “Hey, did you see me do that? Was it too quick for you? Watch closely, I might do it again.”

Some groups do it too much, some don’t seem to grasp its appeal and throw the gesture away. The boys of St Peter’s, who can be staunch as, when they want to be, are experts. Thirty-five of them lined up later that day on the Tongan stage in two seated rows and did a dance using only their hands, wrists and the head flick, and you never saw anything more graceful in your life.

Sisters from Samoa were there to have fun: you could hear the shrieking all over the park.

The Samoan stage was set up in front of a natural amphitheatre which quickly turned into a seething cauldron, noisier by far than the Maori stage, which took itself more seriously. Sisters from Samoa were there to have fun: you could hear the shrieking all over the park. On the diversity stage the Botany Downs kids did an athletic and very witty Chinese lion dance, although it felt more like an exhibition than a competition: the intensity wasn’t quite the same.

Helene Wong, born in New Zealand, has given her memoir the title Being Chinese. It’s an intentional reference to the historian Michael King’s 1985 book Being Pakeha. Wong grew up knowing very few other Chinese New Zealanders, assimilated like crazy, but always assumed she was more Chinese than not. Until, that is, she made a pilgrimage to her ancestral village in China in 1980. There, she says, she realised what she had not known before: she was a New Zealander more than she was Chinese.

She quotes King, who was a friend: “We who were born here have no other home. We have ancestral roots elsewhere, but that is not the same thing.”

Aucklanders, a third of us with ancestral roots elsewhere, are busy making our own homes here. Following the 2013 Census, Statistics New Zealand made predictions for the next 25 years about where we’re all going to do it (see our pie charts, pages 50 and 53). There are not many surprises.

The balance of people living in the Waitemata area will tip towards Pakeha and, even more so, Asians: that’s the central city from Herne Bay and Grey Lynn across to Parnell. In Manurewa, there’ll be relatively fewer Pakeha, more Maori and many more Pacific Islanders. Basically, if you can spot a trend at the moment, expect it to continue but at a faster rate than now.

That’s possibly tautological: demographic predictions are largely based on what’s already happening. The pie charts show the expected population changes for Auckland’s four main ethnic groups (Pakeha, Maori, Asian and Pacific Island) in every local board area except Great Barrier, where little will change. If you’re uncertain where you are, check the map opposite as well.

Standout trends? Devonport-Takapuna looks similar to Waitemata: Asian numbers will double and the current three-quarters proportion of Pakeha will slip closer to half, while the proportions of Maori and Pacific Islanders will remain as they are. The same trends will apply in Albert-Eden, Henderson, Kaipatiki, Orakei and Upper Harbour.

The Asian population will grow to around half in Howick, Puketapapa and Whau. The Pakeha population will drop to around a third in Henderson, Maungakiekie-Tamaki, Papakura and Whau. The Pacific Island population will grow to nearly half in Manurewa. It’s already over half in Mangere-Otahuhu and will grow to two-thirds.

The Maori population, despite doubling in many places, will remain at a quarter of the whole in Manurewa and Papakura, and everywhere else will be even less than that.

Pakeha are not the losers in any part of Auckland’s changing demographics. There’s no wholesale displacement under way, and areas of relative dominance will remain that way. Waiheke will stay overwhelmingly white.

Auckland was the only part of the country to record a decline in its Maori population.

The population in decline is Maori. Not only are Maori under pressure from immigrant growth, there are fewer in real terms. Auckland was the only part of the country in the last census to record a fall in its Maori population.

This has profound implications for a whole lot of economic, cultural and social factors, including the Treaty of Waitangi. The bicultural principles of our founding document as a nation recognised two peoples, Maori and Pakeha, but as Mai Chen says, “the Pakeha face of the treaty” is starting to look very different. In Auckland, Maori’s place as mana whenua is at risk of being even more marginalised than it is now.

Kapa haka has three messages. One: We are at one with the land and with our ancestors, and with the birds, and with the universe. Two: We are going to rip your balls off and stuff them down your throat. We are so gonna mess you up. Three: God.

The top-division Maori contest at Polyfest was totally on message: every crew was unabashed, proud, inspirational. Nga Puna o Waiorea (NPoW, otherwise known as Western Springs College), were the champions for four straight years to 2015, and that meant they performed last on the last day, the Saturday.

While they waited, the black-clad NPoW kids hung around like sharks: they were royalty and they knew it.

The atmosphere was thumpingly exciting. Before each group performed, supporters flooded into a special area roped off for them in front of the stage, and when the show was over, the supporters jumped to their feet to haka the performers back.

The girls of James Cook High School, in full traditional costume with white poi at their wrists, jabbed to the right, poi flashing, and at the end of their outstretched arms each of them suddenly brandished a mere. The dance had a ruthless beauty, elevated way beyond entertainment.

The boys from King’s College — yes, King’s College — came out with their taiaha, long spears. They sang, in a quietly melodic fashion, but the mau rakau (the spear work) had their hearts: the dance was fast, dangerous and beautifully co-ordinated. The taiaha were swung like poi: get it wrong and you’d take the next guy’s head off.

Kia Aroha College is just a few kilometres down the Southern Motorway from King’s, on an entirely different planet: they had white sticks instead of wooden spears and each performer wore a ragtag assembly of whatever costume he could find. But they were good: the singing, the mau rakau, the works.

Schools from the west were strong: Rutherford, Kelston Boys and Girls, Te Wharekura o Hoani Waititi Marae. Massey College brought the bogan, with a performance whose wildness threatened at every moment to disrupt the discipline, yet somehow also managed to be more melodic and more creative than many of the others.

I have no idea if they got points on or points off for that. If you had the technical knowledge, you’d get more out of watching than I did. But you don’t need to know anything to respond to the visceral intensity, the creative flair, the precision and lyric beauty. And the infectious enthusiasm.

Finally it was Nga Puna o Waiorea. They were so thrilling. They flew the 1834 flag of the united tribes during their mau rakau. They leapt higher and landed more thumpingly, they sang with more beauty, they spoke more affectingly, with immense oratorical style. They had many soloists and personified many great characters, but the sum was greater: the concept that drove the show, the superb execution, their commanding presence.

As they finished, groups from all the other schools, students and adults, leapt to their feet. NPoW was honoured not just by their own supporters but by the entire crowd. It was an electric finale.

Still, in a big upset, they didn’t win. The new champions are Hoani Waititi.

Back to the economy, which may indeed, as Chen says, be what this is really all about. She heads an organisation called the Superdiversity Centre, which this year produced a major report called the Superdiversity Stocktake: Implications for Business, Government and New Zealand. The report is extremely critical of the way New Zealand business fails to grasp the potential offered by ethnic diversity.

The centre asked business leaders to do a self-audit of their “CQ”: their cultural quotient. The average score was two out of five. CQ in relation to Maori was low; in relation to Asians it was “extra low”.

The people being discriminated against aren’t the only ones to lose out: the businesses doing the discriminating suffer badly too. Chen says most companies don’t know how to reach customers who are ethnically different, and if they do manage it, they don’t know how to provide good customer service.

They don’t consult on policy or business practices, they have negative attitudes to Asian immigrants and they don’t know how to go about changing any of this.

“They lose market share,” she says. If you’re looking after the needs of only white people, you’re losing maybe half your potential customer base.

And they miss out on good employees. Migrants and their children make up 56 per cent of the job market and it’s not uncommon, Chen says, for 90 per cent of job candidates to be Asian. Because of the points system, migrants are “brainy or highly skilled or students or rich”, but they routinely get overlooked.

Only five per cent of board members in the NZX top 100 companies are Asian. Chen is also involved with a group called New Zealand Asian Leaders, and says its 200 members have all experienced the bamboo ceiling. Like Wong and Chen herself, they’re angry.

“Do you know what makes them angry? The say, ‘We came, we worked hard, our kids did well and they’ve got good English skills, and still they’re discriminated against.’”

There’s an audience for this analysis. Since November, the centre’s report, 500 pages long, has been downloaded 95,000 times.

The easiest and most obvious way in which to enjoy Auckland’s multiculturalism is through food. The restaurants and takeaway shops, the night markets, the International Cultural Festival held every autumn in Mt Roskill. So much of it is splendidly good. Marlon James, the Jamaican winner of the 2016 Booker Prize who came to the Auckland Writers Festival this year, doesn’t really buy this line. “Eating ethnic food isn’t valuing diversity,” he says. “It’s just eating.”

Helene Wong compares the Labour Party’s list of property buyers with “Chinese-sounding names” to the anti-Chinese racism promoted by Premier Richard Seddon over 100 years ago. “This time we didn’t get called ‘slimy slit eyes’ [as one newspaper charmingly put it in the 1890s], but the sentiment was similar.”

Labour, until very recently, was the party that most obviously championed ethnic minorities.

The National Party, on the other hand, has worked hard in recent years to modernise its image. Party membership, judging by attendance at party meetings, reflects a distinct appeal to Chinese, Korean and Indian groups.

At a recent conference, they were all so comfortable with ethnic diversity that, while Korean-born MP Melissa Lee was chairing a session, Cabinet minister Paula Bennett got up on stage and made jokes about “the irritating Korean”.

Susan Zhu says she thinks we’re “doing quite well”. Then she adds, “I wouldn’t say it’s nothing. A few years ago, there was no one [of different ethnicity] in the banks, or in the other service industries.”

Wong says peer modelling is the key. If you disapprove of someone in your car shouting at an Asian driver, find a way to say so.

Mai Chen says, “New Zealanders like being New Zealanders.” And, she adds, a core part of our identity is a sense of fairness. Wong says much the same: our core ethics are friendliness and giving people a fair go, and maybe we should add inclusiveness and respect.

This isn’t even about Auckland, really. We live in the world. Populations everywhere are mobile and becoming much more so, some through choice and many others through necessity. Immigrants will always be everywhere. It’s what we are. So is there another city working it out better than us?

Chen says, “I don’t think so. Asians feel discriminated against in Vancouver, too.” Wong says multicultural acceptance is already widespread in sport, business and the arts, so why wouldn’t it follow into everything else?

By mid-evening at the Lantern Festival, the karaoke was all done and most of the food stalls had run out of food but still the crowds pressed forward. Chips were all most of them had left, and seriously, that night of all nights, who wanted chips?

The big plaza in front of the museum was packed. As older couples and families drifted home, flocks of young people congregated on the flagstones in the still, warm night. Sober, excited, the boys out with their boys, the girls with their girls, strutting, posing, rushing from one huddle to the next. Fairy wings with flashing lights were big this year.

Together alone, as Neil Finn used to sing. We stand in the same place and we’re different.

Everyone clumped in with everyone, all of them looking, looking. The big thrill, complete with its frisson of risk: the shared, elbowy tribal experience. Together alone, as Neil Finn used to sing. We stand in the same place and we’re different, and sometimes that makes us a bit anxious, but it’s fine. It’s called a city.

As I walked away, a whole lot of handheld lanterns were drifting low and free across the playing fields, floating like illuminated flotsam on a wide fast-moving river. Completely random, and one of the most beautiful sights of the evening.

Who wants to live in New Zealand?

Among the 124,000 people who arrived in New Zealand in the year to March 2016 and intended to stay at least a year, by far the biggest group (25,767) were Australians. Next were Indians (13,486) and Britons (13,445). Chinese immigrants came in fourth, with 11,722. Following them were 4000-5500 immigrants from the Philippines, America and Germany.

The 2013 Census revealed that 25.2 per cent of the New Zealand resident population was born overseas. In comparison, among European countries dealing with supposed “floods of immigrants”, the rates are in the teens. Britain has 12.5 per cent and France 11.6 per cent. Italy, the landing place for many refugees fleeing wars in North Africa and the Middle East, has 9.4 per cent. In Hungary, where they’re so terrified of migrants they’ve done their best to keep them all out, the figure is 4.5 per cent.

The most common source country for foreign-born New Zealanders is still Britain, with more than 240,000. China is a distant second, with 89,000. India, Australia, South Africa, Fiji and Samoa all now have 50,000 to 70,000 people born there and now living here.

External sources mentioned in story:

Superdiversity Stocktake: superdiversity.org

Being Chinese, by Helene Wong: Bridget Williams Books, $39.99

Matariki Festival: June 18-July 17, matarikifestival.org.nz.

Read more: Stories from the world’s fourth most diverse city.