Sep 26, 2016 etc

The epic rescue that founded the Karekare Surf Life Saving Club.

This article was first published in the January 2013 issue of Metro. Photos by Alistair Guthrie.

Her name was Hazel Bentham. Bob Harvey set me up with her, talked her up one blustery night in a bar in Wellington of all places. We had been talking of our beloved beach, lonely on Auckland’s untamed coast, and of the surf and the boys of summers past, and the girls. So he mentioned her and told me her story. I fell for her there and then, really. And I went to find her and bring her back with me, just as other men did in that summer years before.

Charles Hamlin, November 2012

SHE LAY OUT where the summer sun etched the water silver and gold, trapped beyond the great waves that broke hard and white in endless chains on the black sand shore. To those watching from the beach she seemed to shimmer in and out of existence. There was debate among the growing crowd as to whether she was still alive at all.

Their eyes moved between the distant sun-gilt figure in the water and the loose knot of young men on the beach. Tough-looking characters, tanned and fit, they stood quietly, bound together around the drum of the tangled reel line. They were strong swimmers, and well used to these colossal waters, but even they had been shaken by the temper of the sea.

Two of them had nearly died striking out toward her through the heavy surf. The sense had left several others who knew their own strength in the water and saw a life about to be taken by it. They had needed to be held back from heading out toward her. There seemed little to be done now.

But the men didn’t have it in them to simply give her up. They were sure she was still alive out there. And the current that had swept her northward for a time had at last relented. She was drifting back into their reach, in theory at least. Now another man said he would go out into the storming water. There was, he said, always a chance he might reach her.

The crowd considered the chances of another attempt. They were day-trippers mostly, weekend runaways from the city. Auckland lay less than 20 miles from this wild coast, but the ravines and valleys of the Waitakere Ranges took up half that distance. It was a long journey to get here, through dense rainforest on a hard road that in places barely clung to the hills.

The ranges were all that remained of a vast ancient volcano, worn down over millions of years by one of the roughest seas in the world, but they still faced that pounding water with a cliff face many hundreds of feet high and many miles long. This place was a fracture in the rampart, cut sharp and steep into its hard dark stone. Karekare, the Maori had called it: “Turbulent water”.

The bush rolled like a verdant avalanche down the valley to the black sand beach.

The bush rolled like a verdant avalanche down the valley to the black sand beach and the tumbling white water. The wave-beaten shore stretched on a line that ran north and south for what might have been forever. Across the whole westward sweep it was the same with the sea and the sky. The high cliffs and hills wrapped the east and pressed you hard against that endlessness. And all around you was the eternal pulse of the surf, magnified by the valley into a sound like rolling thunder.

Karekare was a place you either loved or ran from. Some felt naked and pinned like a butterfly on a board. For others it was Promethean, the power of the place like a dangerous gift, and “the voice of the surf”, as they might have quoted Conrad, “was like a brother”. That was how it spoke to the men who now stood around the reel line, still determined to bring the woman back to shore. They had made Karekare a weekly pilgrimage over the years. Members of a cycling club, each Saturday they rode a route that smacked of penance to get here.

Setting out from the city they found the rough road that cut up into the ranges, pushed their legs into the slow fire of the hard inclines, skated on loose dirt around precipice turns. They rode hard, acid burning the blood, until they came to the crack in the ragged green horizon where the ocean ran through and the valley came at them in a final, wild, downhill rush to the beach, their wheels sliding on the sharp, steep bends, the smell of brake rubber mixed with the scent of the sea.

They washed off their journey in the surf and stayed the night, cheerfully mothered by the woman who ran the boarding house where they bunked down. Sundays were spent swimming at the beach or beneath the nearby waterfall that fell like blue-white lightning down a cliff of black volcanic rock. They were young and fearsomely fit. They never lacked for company.

The physicality of Karekare seduced those who found it and dared to stay. They felt alive in the energy of the surf and the drama of the landscape, but the fact was that sometimes they died here. Five people had drowned over the past few summers, and now here was this woman, stranded beyond the break for a whole three hours. Lives lost here were usually taken in minutes: three hours was the measure of lifetimes. It seemed scarcely credible she could still be alive.

Far out on the swelling sea the woman knew nothing of such things. For her time had become one long unbroken moment. She had not struggled when the rip dragged her out. She knew to do so was hopeless. Better to conserve her strength and swim back once the undertow released her.

But she had been thrown through the break with a violence that shook her. Looking back over the huge walls of surf she had known she could never scale them alone. She had concerned herself with staying alive instead, watching the shore with wide dark eyes. She knew they would come for her. She had seen, and even heard through the roar of the surf, the clamour of the growing crowd and the shouts of the men organising her rescue.

She set herself to help them as best she could. By turns she swam and rested, conserving her energy and trying to keep herself within reach of the shore. Then in disbelief she had seen men strike out for her only to be hauled back; seen them reach for her only to fall far short. She realised with a suddenly racing heart that she was beyond another’s touch and alone. Utterly alone.

A dull realisation seeped into her: this place was going to steal all that she was and all she ever would be. She was going to die on a fine summer’s day. The cold touch of it affected her less than she’d imagined it would. Some part of her felt it was enough now; she had done enough — all that could be asked of her. She had kept her head where so many others had lost theirs and swallowed a sea-full of water. Well, much good it had done her.

Alone and lonely on the edge of an endless ocean, Hazel Bentham calmly crossed her arms over her chest and lay back on the sea. She was young and lithe and bronze, a living beauty posed as the prepared corpse upon the rippling blue sheet of water. An ocean that had rolled a thousand miles and more moved heavy and rhythmic against her, like some uninspired lover, careless and cold and unwanted. She closed her eyes and let go of something inside her.

LONG BEFORE THOSE few hours, and many lifetimes ago, Hazel Bentham walked down to the sea with the man she was soon to marry. It was a little before two in the afternoon. The full heat of the day was a weight they carried over the broad beach. The baking air veiled the view and the dark sand, hot as embers, dragged at their heels. In front of them, the waves fell white and cool against the stretching blue ocean.

When they finally reached the water its touch seemed like life itself, like youth and promise, and the foaming surf like flirtation against their skin. The two of them laughed in the tumble of the waves. She didn’t notice when the wraith-like current took hold of her, and in just a few heartbeats the rip swept her away, beyond the arms of her man and far further still.

She was dragged close by the black rocks that knifed out from the cliffs at the northern edge of the beach. The rocks struck deeply into the surf, a hundred yards and more. One of the men from the cycling club stood atop them, taking in the view of sand and sea that seemed to stretch forever southward beyond the dragon’s tooth of Paratahi Island. His shouts raised the alarm. On the beach his mates from the club turned at his cry. They followed his pointing arm and saw for themselves Bentham being swept away.

They started running, away from the surf and toward the boarding house nestled half a mile away in the bush at the base of the valley. An old lifeline was kept there. With no surfboat here, they would need the line if they were to have any chance of bringing her back to shore.

Their feet foundered in the hot sand, rasped over the stone bed of the cold stream, scrambled up and over the lower slope of the huge razorback cliff they called the Watchman, and at last met the soft grass of the house lawn. They hauled the line from the shed and headed back, sweating over grass and hill and stream and the vast dull oven of the beach.

By the time they reached the water’s edge she was out at the break. One of them, a man named Turner, hastily tied the line around his waist and battled out toward her. Through the big waves the 300 yards of old line played out. She had been taken out so far and so fast that it fell short of her, and out at the break Turner found he was as exhausted as the line itself. The boys on the beach pulled him back through the white water.

Turner made the shore again at the limit of his reserves, his waist marked red raw where the line had burnt the skin. He stumbled onto the beach. Others supported him up past the tide line.

Someone ran back to the boarding house and placed a call through to the surf club at Piha. The club was little more than a year old, its clubhouse only half built — the Duke of Gloucester had jokingly declared it “half open” when he had visited just a few weeks previously. But what it lacked for a roof it made up for with fine swimmers.

More than that, the club had a precious surf reel — 440 yards of tough Indian cotton line, spun around a drum held in a wooden frame that could be easily carried. Taking it would leave the crowded beach at Piha with nothing but a lifeline, but the Piha boys did not hesitate. Four of them hauled it onto a truck and drove around the few miles of drunken, bush-clad curves between the club and Karekare.

They went as fast as they dared. The Cutting, the breakneck stretch of road down to Karekare, was a notorious white-knuckle experience and the Piha boys hurtled down it on the edge of control, the wheel fighting the driver’s hands, the brake drums smoking. The wheel arches grazed the clay road banks. Tyres spat dirt and dust as the swaying cab leant into the flax and toetoe that beat a stuttering, scraping tattoo on the bodywork.

Pieces of the truck shook loose and fell away. The boys clung on. They made the beach carrying the reek of ruined brakes.

Quickly they set the surf reel on the sand and Andy Sutton shrugged into the belt attached to the line. He sprinted into the water, hurdling over the dying waves. Two of the others, Dan Sinkovich and Sid Moore, carefully played the line out over their heads, keeping pace with him. Soon he was into the breaking surf and crawling out with fast, clean strokes.

Sutton was not built on classically heroic lines. He was slim, a lightweight, and with an open, youthful face that seemed more innocence than experience, but this was deceptive. He was built like No. 8 wire and fearsomely able in the surf, capable of swimming strongly even with the awkward burden of the belt.

It took a solid swimmer to haul hundreds of yards of line out through the surf, but it took nerve to do so while encumbered with the belt. The canvas harness wrapped around the torso and was packed with thick cork blocks. In heavy surf on a tricky beach it could be a death trap. The beltman couldn’t take it off alone, and if the line tangled he risked being dragged under and drowned. Yet the belt’s buoyancy meant he had to endure the full force of the waves as he swam out, unable to dive beneath them as they broke and fell. It demanded superb confidence and stamina.

Sutton had both, but as he swam out he was lifted high by every mammoth wave, smashed hard backward as they broke against him, and then dropped suddenly as they let him go.

He was taking a beating and he knew it, every set of waves like a round in the ring. Slowly he became punch-drunk with the blows. The tang of seawater turned bitter at the back of his throat.

Sutton raised his head for the sight of her every so often, using the back of a breaking wave as a vantage point. His swift crawl slowly ebbed in sureness and strength.

The last of the four Piha boys, Cliff Holt, had made his way down the long wall of black rock at the northern edge of the beach. Split and shattered by ages of breaking surf, the rocks rose from the sea like the wrecked hull of a ship. Holt stood precariously on the twisted prow, waves breaking around him, shouting directions and encouragement to Sutton.

Urged on by his friend, Sutton went out to the last yard of the quarter-mile line. It fell short of her. He came to a dead stop in the sea with a racing heart.

Sutton was near the break, where the waves built in colossal curving walls of sharp blue. They surged up before him, consumed him, and then the belt dragged him up through their crushing weight and into the sunlight. He caught sight of her: she was alive out on the swell. He watched her swim sporadically then calmly rest, buoyant on the rolling ocean. That at least was something. Panic was what killed people out here. Clearly, she was tougher than most. He signalled for the boys to haul him in.

Once back on the beach, Sutton told the others that she was still alive but beyond the reach of the line. While he rested, the Piha boys and the Karekare stalwarts of the cycling club tied the old boarding house lifeline onto the surf club’s reel line. They then carefully wound both back onto the drum. It made for nearly half a mile of line, a tremendous reach but a huge burden in the water. Sutton, battered but determined, declared himself recovered. Again he slipped into the belt and headed out.

She had drifted even further from them by then, far beyond the break. The current was sweeping her north to the next bay, a desolate place in the arms of a sheer curving cliff face 600 feet high. Sutton had to punch out straight and deep through the waves and then cut across, heading towards her parallel with the shore, so that the line wouldn’t snag the rocks.

At Piha two weeks before, to the very hour, Sutton had failed to save another woman. She had been within reach but hidden by the glare of the sun on the breaking surf. He had stayed out in the waves for what seemed forever, hopelessly searching for her, nearly sunblind in the end.

When she had finally been brought ashore they worked for two hours to bring her round, but it had been no use. Sutton could still see her lifeless face on the black sand. She was 20 years old.

It was impossible not to take it personally. He had saved many lives, but the unreasonable truth was that a single defeat conspired against all those victories. So he wasn’t turning back now, not from this girl. He kept going against the crushing ocean; right out to the very last inch of the 740-yard line. But he didn’t even come close to her.

Exhausted, he found himself near the wall of rock where Holt stood, on the edge of what the Karekare boys called the Cauldron. Even at its gentlest, the Cauldron boiled madly. The chop of the water followed all directions and none; it was impossible to predict and a terror to fight through. Once they fell into the Cauldron, not many people came out alive.

Trapped in the belt, he was dragged down beneath the frothing sea.

The long line Sutton trailed snared on the Cauldron rocks. Trapped in the belt, he was dragged down beneath the frothing sea. Frantically the boys on shore tried to haul him in. They picked up the reel drum and sprinted down the full length of the beach, trying to straighten the line as they pulled it taut. There was little else they could do.

To send another swimmer into the Cauldron to rescue Sutton would have been near suicidal. And anyway, Sutton would be long dead by the time his would-be rescuer reached him.

Then, by some simple chance, the pounding water shook the line loose. The boys sensed the slack and hardly noticed the strength it took to wind the line back onto the reel. Through the waves came a tumbling cargo. The deadweight danced in the surf. Sutton was barely conscious but somehow still alive.

AUCKLAND LIES IN the embrace of two great oceans, which border the east and the west. The two coasts have very different tempers. While the surf is the timeless pulse out west, in the east the Hauraki Gulf, a sheltered thousand square miles of South Pacific, washes gently into a flat shining harbour. “Water like obsidian”, the Maori called it: Waitemata. Its smooth polished water was only 20 miles from where Sutton was being hauled, near lifeless, from the waves.

The seaplane base was carved into the hard clay of a headland on the harbour’s millpond upper reaches, near the little village of Hobsonville. The base was still a work in progress, just a broad grass airfield with two hangars and some barracks and workshops. The plain concrete buildings stood on two sides of a small apron, from which a single slipway slid into the water.

A large biplane, a Fairey IIIF fitted with floats, had been manhandled down the ramp and onto the flat sea. Officially it was a job that took 15 men; on this sleepy Sunday, it had been done in record time with just eight — all that could be rounded up.

Squadron Leader Leonard Isitt watched as they readied the plane for takeoff. He was still annoyed that the message had been delayed. It had eventually been delivered to him by hand — by a Post Office worker on a bicycle of all things. Thirty telephone lines ran to the Orderly Room switchboard at the base, a lauded network of wires reaching into city and countryside, but somehow the call hadn’t found a way through. It was unacceptable, especially when a life was at stake.

Isitt had read the telegram from Karekare with hard, sharp eyes that mirrored the mind behind them. His head thrust gently forward in a way that made him subtly bird-like, an appearance compounded by a sharp nose and thin lips. The effect was a hawk-faced look that seemed determined to bore through whatever faced him. He had put the little slip of yellow paper on his desk and immediately gone to find Sidney Wallingford.

Isitt was living proof of the fighting chance. Remarkably, he had survived a bullet wound to the head while serving with the New Zealand Rifle Brigade on the Somme. On recovering, when other men might have been justly satisfied with having “done their bit” and living by the narrowest margin, he had joined the Royal Flying Corps. As a pilot he had survived the equally bloody war in the air above the trenches.

Now Isitt was in his mid-forties, with a senior rank in a small air force, and this base was his command — almost his fiefdom, some quietly thought. The old head wound still caused him pain, not that he ever mentioned it; but it was a reminder of many things. Whenever he was confronted with a fighting chance, he took it. And that meant, since in many ways Isitt effectively was the air force, that the air force got things done — often quite remarkable things.

Francis Chichester, a Territorial Air Force pilot, had been on Isitt’s base years before preparing to be the first to fly solo around the world. Isitt had told him in no uncertain terms that he didn’t like the undertaking, correctly detailed all that was wrong with it, and said that the man had next to no chance of succeeding. Then he had done everything he could to make the flight happen.

Chichester made it all the way to Japan before he crashed, very nearly to his death. In his best-selling book that told of the adventure, The Lonely Sea and the Sky, he called Isitt a man of “excellent judgment” and also a “true sportsman”.

The words made Isitt’s instincts perhaps sound frivolous, but actually they were sharpest when lives might be saved. Any man who had seen the Somme had witnessed enough futile death for any lifetime. In 1931, Isitt had press-ganged every civilian aircraft in Auckland and personally led them into the Napier earthquake zone, bringing in supplies and ferrying out casualties from the burning ruins.

Now, like the men from the cycling club at Karekare, like the surf boys from Piha, Isitt showed no hesitation. He decided that he would risk men and machines to save the life of a woman he had never met, who might even be dead.

Isitt knew that surf of any kind, and especially the fearsome stuff out west, would tear apart the aircraft he had to hand on the base. And strong winds and stronger swells meant that it was often impossible to even put a seaplane down near the west coast beaches. But there was always a chance that a skilled pilot might just be able to land safely off Karekare, dare the nearby surf line, and carry the woman off.

There was always a chance that a skilled pilot might just be able to land safely off Karekare.

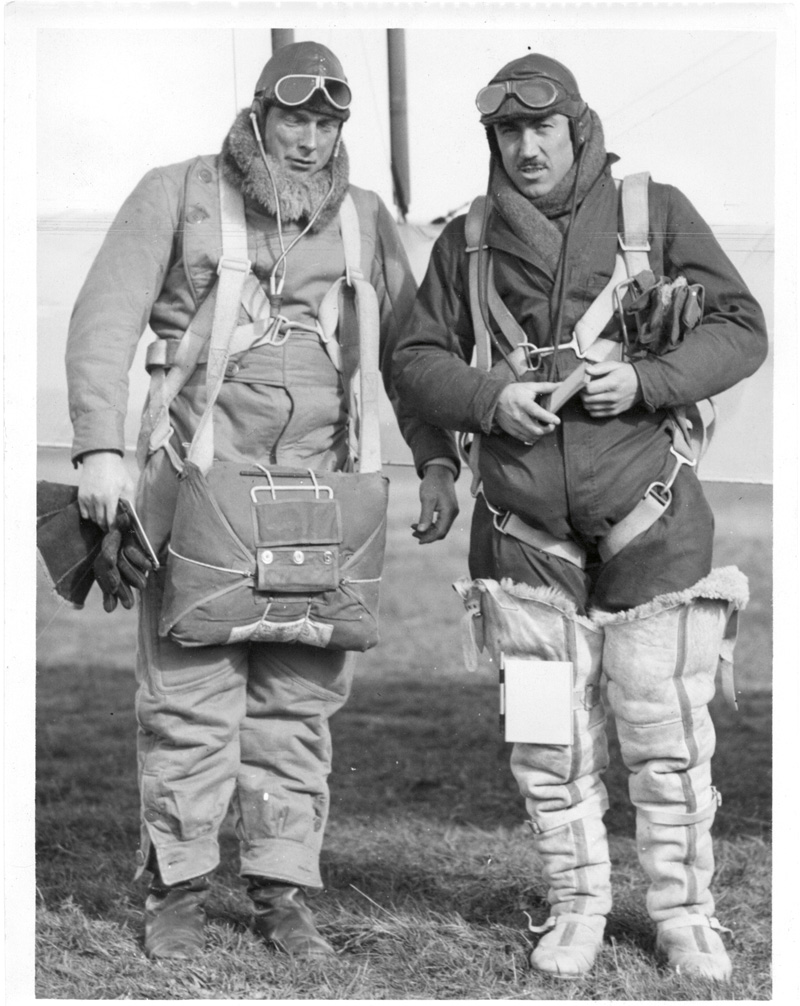

Isitt had done most things you could do with an aircraft, but he had ever done anything like this. Nor had he heard of it being done. The risk to aircrew and plane was horrendous. It was fortunate that in Flight Lieutenant Sidney Wallingford he had a pilot who might have been tailor-made to take it on.

Wallingford was the inheritor of a military tradition. His father had been no less than the greatest marksman the British Army had ever known, and had won the Military Cross with the Auckland Battalion at Gallipoli. The son had followed his father at the first possible chance and had not been found wanting.

In 1916, barely out of Auckland Grammar, he worked his way to England as a greaser in the Merchant Marine and immediately enlisted in the Artists Rifles. His qualities had seen him quickly commissioned. He went on to fight with the Army of the Orient in the Balkans, and then joined the RFC in the last year of the war, learning to fly in Egypt. In the 1920s, he became an expert at flying seaplanes and, along the way, the finest shot in the Royal Air Force.

When Wallingford had transferred home to New Zealand in 1929, no less than Lord Trenchard — a fearsome godfather-like figure in the RAF — had gone out of his way to tell Isitt that the fellow was a “good sort” and “keen”. More tellingly, perhaps, the commandant of the RAF Staff College said he possessed “resolution, determination and strength of purpose”. That was the man in six words, all right. Isitt found him at ease in his quarters.

Wallingford looked like the archetypal sergeant-major, and had a similar fondness for drill. He was tough, self-disciplined and devoted to duty. Among the ranks he was well respected, but to them it was merely rumour that his hard exterior hid a contagious laugh and keen sense of humour. He stood ramrod straight in the wilting afternoon heat and listened as Isitt told him of the message.

A woman had been swept out to sea at Karekare, Isitt said. She was beyond the breakers and the reach of the shore. One of the locals there, a young pilot named Badham, had thought to contact the base and ask if anything could be done. Isitt thought it could. He said time was pressing if they were to save her. She might well be dead already.

Wallingford calmly noted the dangers of a rescue mission, and that even a minor mishap on that wrecker’s coast might be fatal. He summed up the many risks with the quiet observation it seemed “rather a tall order”.

“Go over and have a look,” Isitt had told him with equal understatement. And so Wallingford had roused the base from its weekend rest.

Now Isitt stood by a little de Havilland Moth floatplane that was waiting to follow the IIIF down the slipway and into the sea. Wallingford would be heading into a dangerous business. Isitt would follow him in the Moth, to keep an eye on things. The heat of the late summer afternoon seeped out of the concrete apron. The roar of cicadas that had filled the air was now drowned out by the bass rumble of 500 horsepower.

Down on the water, the big IIIF floatplane had its engine idling, 12-foot propeller a scything blur.

Men in waders held onto the aircraft’s floats, standing waist-deep in water ruffled by the prop blast, their heads barely above the floats themselves as the big machine towered over them. The floatplane was 13 feet tall, with a wingspan nearer 50. The fabric-covered machine was finished with aluminium dope and shone silver, and its long floats glared sharply white.

The cat’s cradles of wires, strung taut between the struts that held the upper and lower wings together, intermittently reflected the sun. The plane flashed like some intricate heliograph, silver on a silver sea.

The men in the water laboured with the heavy, roaring reality of the brute. Its single 12-cylinder engine deafened even at idle, and the exhaust pipes snaking under the fuselage breathed heavy fumes at them. They turned their heads away and hurriedly worked the beaching wheels from the floats.

Wallingford, sitting now in the cockpit 10 feet above the water, signalled them to set the machine free. As the men moved clear, he sent a short blast of revs through the engine. The aircraft went smoothly out into the channel.

From the observer’s cockpit right behind Wallingford, Corporal Alwyn Palmer watched the shrinking shoreline. Palmer was an aircraft mechanic, not trained aircrew. But on the small base, NCOs and other ranks were pressed into flying duties as needed. And so Palmer, the day’s Duty NCO, now found himself sweating in heavy flying gear, on his way to save the life of a woman all but taken by the west coast surf.

He had no doubt Wallingford would put the plane down on the sea. He knew the man well enough. He also knew the size of the surf that smashed the coast out west, and how even the swell could cripple a plane floating on the ocean. He couldn’t help but wonder, fine pilot though Wallingford was, if once they were down on the sea they would ever fly off again.

Palmer knew that the Australians used aircraft over the surf beaches around Sydney, on shark patrols mostly. He knew it because in the papers you often read of them crashing. Only a year back, a de Havilland Moth searching for a drowned boy had hit an air pocket and nose-dived into the surf. A few years before that, another Moth had gone down just off the coast near Sydney. A bird had struck the prop and shattered it. The crew managed to swim to safety, through shark-infested waters, but after the breakers had finished with the aircraft all that could be salvaged were the spark plugs.

Against the surf an aircraft was a butterfly on a wheel, but duty meant as much to Palmer as it did to Wallingford. “Places duty before self” and “possesses highest principles”, his superiors noted in their reports on him, which they peppered with terms like “very sound”, “reliable” and “highly efficient”.

The Service was Palmer’s life. English-born, he lived in the long shadow of that lost generation that had gone through the slaughter of the Great War, a generation he had missed belonging to by only a year or two. Like many others he felt uneasy with what had been both a denial and a reprieve. He was ready to meet any test that came his way.

Palmer turned from the trailing wake of the floats and readied himself for the takeoff run. Wallingford opened the engine up momentarily, blasting the sparkplugs clean, and then eased it down to check the idling revs. Satisfied, he pushed the throttle all the way to the stop.

The engine hauled a hurricane slipstream over the men in the open cockpits. Palmer stood up in his position just behind Wallingford. As the aircraft began to move, pushing him backward as if with a hand at his chest, he leant forward and tried to improve the takeoff balance as best he could. Beneath him the machine leant back on the heel of its floats as the speed built, the bubbling wake becoming sheets of pluming water.

Salt spray and ozone tang and air like pure oxygen came at them. The floats slapped the face of the channel. The plane slowly tilted forward as if willing itself into the sky. Soon it was skating over the sea.

Wallingford, nudging the rudder slightly to balance the torque of the prop, felt the controls firm up and eased the aircraft off the water. The channel quickly gave way to the open harbour, pooling broadly toward the city. He made a graceful climbing turn in the opposite direction, to westward, to the ranges and the falling sun.

It was now quarter to five. Hazel Bentham had been in the water for close to three hours.

THE RANGES crash over the west coast in a broken wave of volcanic rock some 1500 feet high and 15 miles broad, tumbling inland in places for as many miles again. Beneath Wallingford and Palmer, farmland gave way to outposts of bush, then to scrub, then to dense rainforest clinging to steep slopes. The curving horizon slowly resolved into ragged emerald peaks. The floatplane flew steadily toward them, the two men quiet captives in its small shuddering world.

The engine spat oil at the men in the open cockpits and its roar seemed to squeeze their skulls. The hundred-mile-an-hour slipstream stripped the heat from the day. Their flying suits, so uncomfortably hot on land, now seemed not warm enough. Sweat stuck coldly to their backs.

Palmer held his lean, clean-cut face in the full blast of the slipstream, taking the exhilaration neat. Around them was an almost unbroken circle of sea. He thrilled to the moment. For all the shuddering, deafening fact of the flying machine surrounding him, powered flight was no older than his own 30 years. Wings carried the strength of myth. The sea had stolen a life. Now they were coming out of the sky on great silver wings to steal it back. If they were not smashed to pieces. He looked down at the peaks tumbling beneath them like another storming sea, white cumulus strung atop their dark, seething green. The floatplane was but a silver speck among it all.

A seam of darker blue opened between the sky and the hills, slowly stretching and then tearing wide, and the ocean finally washed across the ranges. Palmer saw the surf for the first time, breaking over Lion Rock out at Piha. Beyond, the coast cut a white line all the way to the northern horizon. He turned his head and saw it was the same to the south. Blue water stretched westward. They might have been on the edge of the world.

Wallingford throttled back and eased the nose down, letting the speed build through the wires as the altitude unwound. A valley opened out beneath them and they rode down its slopes in a smooth banking turn. Palmer clasped the cockpit handholds and swallowed hard, trying to equalise the pressure in his ears. The trees were so close on the forested hills he felt he could touch them.

The floatplane went over the Karekare beach a hundred feet up, a hundred miles an hour and more through the humming wires. Palmer caught the upturned faces of a large crowd before the view became a sudden shock of blue shot through with white. The breaking surf rushed beneath them.

Wallingford climbed again, gaining a couple of hundred feet, and made a long sweeping turn to bring them parallel with the shore. Palmer strained his eyes against the glittering sea below, and saw her.

She was 50 yards out from the surf line, 300 from the northern end of the beach. Whether she was alive or dead it was impossible to tell, but she was there, on the surface.

He slapped Wallingford’s shoulder, pointing her out, and got a curt nod in reply. Wallingford pushed the aircraft further north, beyond the boiling Cauldron and the tall, sea-beaten cliffs, then banked the machine seaward again. They turned tightly on the distant milky haze of the horizon and were quickly heading south once more.

Wallingford began angling the plane for the landing run. They were scarcely a hundred yards from the sheer cliffs and the breaking surf. Beneath them the swell was running at 12 feet or more, as tall as the aircraft itself. Palmer saw that the swell kinked sharply just south of Karekare, where the broad black sands pushed out into the ocean. They were beyond the breakers for now, but a thousand yards on their landing run headed straight into white water. An engine failure or a misjudgment would be the end of them.

Wallingford was not in the habit of misjudgment. He took in the temper of the coast. The strong sea breeze had died out. The swell was the only real danger now. He worked a small wheel in the cockpit, lowering the flaps, winding out the full eight degrees. The crosswind was light enough that it wouldn’t matter. He wanted all the lift the machine had so as to bring it down as lightly and precisely as possible.

He throttled right back, easing the airspeed down to a little above a stall. The machine started sinking steeply toward the sea. They were vulnerable now to the swirling pockets of air around the waves and the hills, those invisible currents that could suddenly throw a plane to destruction. Ahead the sea foamed against the stark line of the Cauldron rocks.

Through the slipstream, Wallingford was gauging the tempo of the swell so as to synchronise his touchdown with its roll. Palmer watched the surf blur into white lines just off the port wings. Wallingford pushed the nose down gently, letting the speed build a little, and then smoothly rounded out. The aircraft sank toward a sea now running like quicksilver until, in the final moment, the water seemed to wrap around them, climbing up on both sides in fast glittering blue.

THE PORT FLOAT hit first and hard, the starboard a moment later and harder still. The shotgun double thump jarred the whole airframe. Spray came over the cockpits. Seawater spattered the men’s goggles and met with droplets of engine oil already distorting the view. The aircraft bounced and hit again a second later. Palmer took a beating from the cockpit as he was shaken around. The machine was ricocheting along the swell. He clung to the cockpit handholds and wondered how badly the floats would be damaged.

In the first yards of the battering landing run they went by the woman where she lay. She gave no sign of noticing.

In the first yards of the battering landing run they went by the woman where she lay. She gave no sign of noticing. The aircraft sank onto the water and quickly lost speed. Wallingford judged the beat of the waves, blasted the throttle and stamped the rudder hard to port. The aircraft came swaying around and began trundling its way back northward. He had to work hard to hold the plane against the energy of the swell. He yelled to Palmer to get ready to go over the side with a length of rope. Palmer ducked down into his cockpit and scrambled about for the line, momentarily seasick without the horizon.

It took some time to make it back to where the woman lay. She went by, a few tens of yards away on their left. Now Wallingford gunned the engine again and set the machine on a straight run to seaward, away from the danger of the surf. He wanted to snatch her from the sea on the first pass and keep going, out into calmer water. He turned and signalled Palmer with an outstretched arm, gesturing a pointed finger down at the port float.

Immediately Palmer hoisted himself up and over the edge, coiled rope slung over his shoulder. Over the side of the cockpit were five sheer feet of fuselage and then another four of emptiness down to the pitching float. Two stirrup-shaped holes were cut into the fuselage; Palmer’s feet found one then the other; he judged his moment then dropped onto the seesawing float.

His boots found the surface but slipped briefly, the seawater streaming over the few ridges that gave the only grip underfoot. He grabbed a handhold and steadied himself, then edged up the bucking float until he stood just behind the lower wing. He took the rope off his shoulder and checked it wasn’t tangled. His eyes searched the rolling mirror of sea. She was gone.

The swell lifted her up into view. She was 20 yards in front, perhaps 10 or less off the aircraft’s track. Wallingford was getting as close as he dared, but the big machine was awkward on the rolling sea. He didn’t want to risk striking her with the float. The plane was at dead idle now but still moving at about three knots, something like five feet passing by every second.

Palmer saw he would have to let the woman float under the wing, wait for her to reappear, and then throw the rope. She would be hidden from view for perhaps two seconds. Once she emerged he would have perhaps another three to judge the distance and throw the rope. Time for only one chance. He had no idea what he would do if she didn’t grab the line. He wore a kapok lifejacket, but his heavy flying gear would surely drown him if he had to get in the water.

She lay on the great ocean, eyes closed and arms folded across her chest, tranquil and still. He willed himself calm as he watched her come closer. She disappeared beneath the wing. He waited on the violently pitching float.

He had his back to the fuselage, watching the place where he judged she would reappear. His left hand firmly gripped one end of the rope and a fuselage handhold for good measure. The line ran around his back and down to his right hand, where the rest of its length was held cleanly coiled. He stood as far along the float as he could, trying not to get thrown into the water.

Finally, she appeared. Her tanned skin was pale, bronze beaten thin, and through it came a disturbing bluish hue. Her hair was awash in a dark crown about her head. There was no hint of consciousness. Palmer judged his moment and threw the line.

To Palmer’s surprise, her arms jerked and she grabbed the line in a steel grip.

The rope fell over her pale arms where they crossed between her breasts and touched her like a live wire. To Palmer’s surprise, her arms jerked and she grabbed the line in a steel grip. Yet nothing else about her changed. Her eyes remained closed and her body still. She floated on the sea as calmly as a corpse. But the line was held tight in her small fists. Her grasp of it must have been purely instinctive; a nervous system twitching.

Palmer had her. Now he had to get her on board.

The rope was anchored firmly around his body. He brought up a light tension on it so as not to jolt her grip as it played fully out. She drifted back, still clutching the line. The momentum of the aircraft swept her behind the float and into its wake.

Wallingford, watching from above, saw that she was being dragged under the water. He shouted at Palmer to bring her in quickly, but his crewman didn’t need to be told. Palmer was hauling on the line, leaning back on the float to balance his effort. Her grip held firm.

As the rope came back through Palmer’s hands, she bobbed over the wake of the float, went by its small twitching sea rudder, and was finally alongside him. He lay down on the float and put an arm around her chest, holding her above the water. She didn’t seem to realise he was there. Her head lolled drunkenly. He held her close, spoke to her, shook her, slapped her face. There was no reaction. He shouted up to Wallingford to take them out to calmer water.

Wallingford opened the throttle a fraction, taking them seaward at a faster rate, then looked back down at the girl in his crewman’s arms. Palmer was lying awkwardly on the bucking float, left arm like a chain-link under both of hers and wrapped around her chest, right hand holding on to a strut. Wallingford saw that he was trying to cradle her head as best he could, but it moved helplessly about. She seemed unconscious. He realised Palmer would not be able to lift her into the aircraft by himself.

The break was 200 yards behind them now, and the swell had lost some of its presence. Wallingford set the engine at a fast idle and tightened the throttle nut to keep it there. If the motor stalled, there was no way to restart it. They would be dead in the water and the surf would soon smash the aircraft to pieces.

But there was nothing for it. He was about to do something at least as risky as setting down off this coast in the first place, but it had to be done.

After Andy Sutton had been taken to safety from the epic swim that had nearly killed him, the Piha surf boys and the Karekare diehards of the cycling club had stood dejected on the beach, debating what to do next. They looked like a rugby team after a hard game badly lost.

The woman had been drifting north and the possibilities of saving her had seemed as exhausted as Sutton and Turner, as played out as the tangled surf lines.

Then the current had relented, bringing her slowly back and displaying her just a few hundred yards before them on the shimmering sea, a tantalising presence for all the torrent of surf that held her from them.

They had watched in silence for a time, hands shielding their eyes against the glare, the growing crowd on the beach a babbling hum behind them. Cliff Holt said he would go out for her.

Unlike Sutton, Holt looked as rough as the surf itself. He had a pugilist’s face and a swimmer’s physique — broad shoulders, powerful chest and slim waist. And he was tall with it; a serious piece of work. He had been one of the five founding members of the Piha club the year before, all of them persuaded by Holt’s brother over a keg of beer that there was a need to patrol the dangerous beach.

The Piha boys knew Holt had as good a chance as any of them of making it — probably better. They would back him.

They untangled the long improvised surf line and wound it back onto the reel. Holt slipped into the belt that had nearly been the death of Sutton. When all was ready, he took the surf at a slow run. He was moving well when cramp crippled him halfway to the break. The boys ashore pulled him back to the beach and for a few minutes they were despondent, but Holt soon recovered. Like Sutton after his first failure, he went out again, more determined than ever.

Holt was within a hundred yards of her when the floatplane touched down. He had seen the rope being thrown but mistook it for a boathook. Now, amid the huge surf 50 yards from the break, he watched in amazement as the pilot of the floatplane stood up in the cockpit, abandoned the controls and stepped over the side of the fuselage and onto the wing. The pilot then dropped down onto the float and helped his crewman lift the woman from the water to lay her on the float.

The pilotless floatplane lurched steeply as some greater wave ran beneath it, building on the shelf. Silhouetted against the falling sun, it flashed dramatically into light and for a moment Holt thought it was going to tip over. Through the waves he even heard the sharpened clamour of the crowd on the beach as they anticipated the same end. But then the plane somehow righted itself, the three figures still on the float.

A moment later, the same wave that had tipped the plane so precariously moved over the break and reached him. It built up a sheer blue wall that turned green and then translucent like stained glass, and he was a part of it before it shattered. It took him down as the belt held him against its force and tried to push him up. Holt emerged on the surface in the calm of the big wave’s passing, drawing the fresh air down into his lungs. He might still be needed yet. Having come this far he sure as hell wasn’t going back now.

As Holt struck out to punch through the break, Len Isitt’s little Moth biplane appeared over the beach behind him. Isitt sent the Moth into a curving turn through the early evening sky and passed low over the IIIF floatplane on the sea below.

There were no radiotelephones. Isitt had no way of knowing what was going on other than by seeing it with his own eyes. A hundred feet up, heading out to sea with lightly banked wings, he leant his head into the cold slipstream to get a better look. What he saw momentarily threw him. The pride and workhorse of his small base was pilotless and tripping drunken circles across the sea as it drifted toward the surf break.

Wallingford heard the Moth go overhead but couldn’t afford to pay it any attention. The woman seemed all but dead. When they had lifted her from the water she was so cold he wondered how she was still alive. She was in shock, unconscious and shivering uncontrollably. Now, on the narrow bucking float, they were desperately trying to revive her.

The sea slapped their faces cold and stung their eyes. Exhaust fumes swirled over them. The float offered scarcely any space to move let alone bring the life back into her. And for all their efforts, the girl’s heart rate betrayed no sign of rising to a stronger, steadier beat.

Wallingford knew she needed safety, warmth and medical attention. But if they stopped working on her now in order to fly her out, she might die before they reached Hobsonville. Stay here, though, and shock and hypothermia would kill her anyway. Stay here, what was more, and the floatplane would soon be broken in the surf.

They had risked enough. He and Palmer had been on the water for half an hour, soaked through with sweat and seawater. They were running only on adrenaline. Stay here and time ran out for all of them. They needed to get her into the aircraft.

It was easier said than done. The cockpits were nine feet above them. Awkwardly, crouched beneath the wing, they edged her forward on the float. Wallingford’s back was soon just a couple of feet from the long slicing blades of the prop. Their quick, threatening beat cut through the thunder of the waves. The warmth of the big engine, now dangerously overheating, radiated through the cowling above him. The snaking exhaust pipe threatened to burn him outright. With his arms beneath hers, he lifted the girl upright on the float and somehow kept his balance.

Palmer had hauled himself onto the lower wing, careful of his footfall: a misplaced step would send a boot through the fabric. Now he and Wallingford carefully lifted the woman up onto the wing. Palmer put his arms around her and managed to heave her to her feet while Wallingford climbed up to join them. The woman remained unconscious, but she was alive and kicking. Literally; her limbs were reacting, even overreacting, to her body being moved. For Palmer it was like dancing with a drunken girl, and his own feet were hardly steady with the pitching of the aircraft.

The three of them were now stooped between the biplane’s long wings. Behind them, taut wires cut diagonal crosses through a space just five-foot-square, with the cowling at one side and two big struts on the other. The last act of the drama had to play out in this confined stage that pitched and swayed.

Wallingford held the girl while Palmer threaded himself through the cross of the wires that held the wings together. Both of them then manoeuvred her through one gap, then another. When they tried to get her to help them by placing her hands on the wires, her grip snapped shut so surely they had to prise her fingers free, one by one, before they could move her further. The bizarre, frustrating business seemed to take forever, but at last they got her through.

The sea was swelling stronger with every passing minute. Wallingford held the girl to him against the fuselage, the two of them blown by the blast of the prop.

Palmer climbed quickly up the footholds on the fuselage to stand half-in, half-out of the rear cockpit. He leant toward Wallingford and took the girl in his arms.

Palmer was a strong man and the girl a lithe and light weight, and Wallingford was helping him lift her, but his legs had long been cramped on the float. He felt the nerves in them twitching with the strain and the balance and his awkward position. Her limbs were flailing, drumming drunkenly on the fuselage and the small glass windshield. He hauled her up.

Isitt was snarling tight circles above them in the Moth. The threat of the surf break was a rising roar nearby. On the wing, Wallingford turned and saw the water pounding itself into a white mist a few tens of yards away. The Karekare cliffs climbed darkly threatening beyond.

One last effort by Palmer brought the girl into the rear cockpit. He took her gently down with him onto the floor, his legs half giving out with exhaustion as he sat back against the cockpit bulkhead with her shivering body against him. Wallingford wasted no time hefting himself back into the pilot’s seat. His hands fell comfortably onto the controls.

In the rear cockpit, Palmer threw lifejackets around the woman to keep her warm as best he could. Moisture dripped from his head onto her face. Whether it was sweat or seawater he didn’t know. Probably it was both. He clasped his hands over the lifejacket he held against her chest and braced his arms out against the cockpit sides. The takeoff was going to be rough. The first burst of engine revs that shook through the airframe went straight into his bones.

Up front, Wallingford was working the throttle and rudder, heading the plane away from the pounding surf line. He was taken aback when he saw the lone swimmer striking toward him through the open water.

Against the odds, Holt had made it through the break. He was now out where the woman had been when the plane had first appeared over the beach, the long line stretching out behind him across several hundred yards of violent white water. He had done it. He had beaten the massive waves with a fantastic swim.

Wallingford sent the aircraft toward the figure making steady headway with an immaculate Australian crawl. Holt stopped and trod water on the swell as the big plane came closer. He saw the pilot wave to him and signal that he had the woman on board. He lifted a hand in acknowledgment.

The machine turned away, its wake washing over Holt before foaming away to nothing. He waited for a time, breathing deeply, watching the plane ride the swell out to sea. Then he turned and signalled the boys on shore to reel him in.

Half a mile out from the beach, clear of the headlands, Wallingford pointed the floatplane northward. Palmer held the girl tightly to him in the rear cockpit and braced them both against the bulkhead. She shivered against him. At least he knew she was still alive. The floatplane swayed gently on the open water and Palmer heard the sea slapping against the hollow floats like a beating pulse. Then the noise of the engine stormed all other sound as Wallingford pushed the throttle open.

Palmer felt the machine rear up, sensed the resistance of the water holding it back. Slowly, palpably to Palmer, the floats began shedding the sea like a skin. Air coughed its way down the hulls. Even so, he knew the ocean wouldn’t let them go without a beating.

The water began hammering against the floats with a noise like men kicking down a steel door. It sounded louder within the drum-tight skin of the fuselage. Palmer simply sat with the girl, taking the beating as it came. Spray was finding them even in the well of the cockpit, but it didn’t matter. He nestled his head against the girl’s to stop it being thrown around.

The airframe jarred as the floats took a battering beneath them, and they were lifted bodily off the bare cockpit floor and dropped down hard, time and again. He gently rebuked himself for not thinking to use a lifejacket as a cushion. The takeoff run went on for two minutes and two whole miles. It felt like forever.

Slowly the violence lessened. The air began to breathe deeply down the hulls. Soon there was only an occasional thud against the floats. Palmer sensed a freedom seeping into the body of the machine. A smile came to his lips. The sound of the spray dropped away suddenly to nothing and he heard the wind humming through the wing wires.

They were in the air, curving over Piha and climbing steadily. In minutes they would be on the still waters of the Waitemata. There would be land under their feet and the summer evening warm on their skin. They had done it. They had bloody well done it.

After four hours, Hazel Bentham had been stolen back from the ocean. Palmer looked down at her in his arms. The aircraft shook her body gently as she shivered on. He felt her breath warm against his neck. Her hair smelt of the sea.

EPILOGUE

THEY STOLE HER back in time, if only just. Wallingford eased the big floatplane onto the still waters at Hobsonville around six that evening. For Hazel Bentham, after four hours crowded by the roar of the surf and the slipstream, there was finally silence. She was carried on a stretcher, still unconscious, over a final few yards of sea.

She had no recollection of her ordeal…She had never flown in a plane before.

She came to beneath blankets and crisp white sheets in Wallingford’s home, tended to by his wife and the base doctor. She had no recollection of her ordeal. It was a great disappointment, she later told reporters. She had never flown in a plane before.

She recovered quickly and returned to her home in Mt Eden, to her work as a maternity nurse and to the man she had been swept away from that day at Karekare. They were married not long after. The couple donated a week’s wages to the Piha Surf Life Saving Club.

Bentham went on to live a long life. A fine nurse, she was also a strong advocate for the rights of children and spent her later years as an administrator in the Plunket Society.

It was her remarkable toughness and courage that saved her life as much as anything. She became a minor celebrity that summer of ’35. Her story had it all: a brave and beautiful girl swept seemingly beyond rescue; bronzed young men who refused to give her up; dashing flyboys who saved her when her time had all but run out. The media made the most of it.

The surf clubs took their chance to make their case in the press. In a heartbeat, the Piha boys had put their own lives at risk to save Bentham. But as they told the papers, such selfless acts went on across the country every weekend all through the long summers. Surf clubs saved hundreds of lives every season, even though their efforts were hampered by lack of funding.

For a certain breed, though, saving lives is its own reward. Bentham’s rescue proved an inspiration to the men of the Manukau Amateur Cycling Club, who decided to dedicate themselves to the beach they had long since made their journey’s end. Before that summer faded, they formed the Karekare Surf Life Saving Club. The clubs at Piha and Karekare have ever since shared a brotherly bond, one of great friendship and great rivalry. It was born the day Hazel Bentham nearly died.

The first correspondence the Karekare club received was an account from the Royal New Zealand Air Force for Bentham’s rescue, to the considerable sum of £40 (over $5000 today). It has never been paid, but the debt has long since been settled.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Karekare surf boys enlisted together, 29 of them embarking as one on what for some would be their last adventure.

It was the same at Piha, and at most of the surf clubs around the country. Piha lost five men, four of them pilots, and one of the Karekare boys was shot down over the English Channel. The surf boys had a thing for wings, and many of them joined the RNZAF.

They helped swell the air force ranks from the mere hundred men of 1935 to over 40,000 at the height of the war. They were led by Len Isitt, promoted to Air Vice-Marshal, who became the Chief of Air Force. Sidney Wallingford was made an Air Commodore and took charge of the 25 frontline squadrons in the Pacific.

Alwyn Palmer was commissioned when the war began. He led the Hobsonville unit charged with bringing urgently needed aircraft quickly into service, and in 1946, having climbed to the rank of Squadron Leader, was awarded an MBE for his “exceptional engineering ability and devotion to duty”.

The Hobsonville base expanded dramatically, but is gone now, recently given over to Hobsonville Pt, site of Auckland’s newest “township” (and the recent fatal tornado).

With the hundreds of new aircraft that flooded into RNZAF service during the war, there was little use for the vintage floatplane that rescued Bentham. The antiquated wings that saved her life were unceremoniously scrapped. Her rescue quickly became the forgotten start of an equally forgotten chapter of the war.

At great risk, the RNZAF undertook many air-sea rescue operations in the Pacific, saving the lives of hundreds of Allied sailors and aircrew who would otherwise certainly have been lost. It is a tradition kept today by 5 Squadron of RNZAF Base Auckland.

For their part, the surf boys kept wings close to their hearts. Wings are the motif of almost every surf club crest. The founding members of the Karekare club decided on the imagery of a cycle wheel clasped by the outstretched wings of an eagle.

The fact it was the flyboys who carried off the girl that day prompted the Piha club, at considerable cost, to buy a surf boat, claiming that with one they could have brought Bentham ashore in 30 minutes. Perhaps proving the point, in 1939 they won the country’s first surf boat race. Eventually, to beat the biggest waves, they resolved to get some air power of their own.

In 1971, the Auckland surf clubs got their hands on a helicopter, thus pioneering the first civilian rescue helicopter service in the world. A decade later, inflatable rescue boats became a more cost-effective answer, but by then the helicopter service was saving lives far from the beaches. It went on to inspire similar services in both New Zealand and Australia and lives on today as Auckland’s Westpac Rescue Helicopter.