Jan 25, 2018 Crime

The vanishing

Three women have disappeared without trace from the Piha-Mercer Bay area in little more than a decade. A Karekare identity who took part in the searches for them considers a darker side of Auckland’s wild west coast.

It was said her husband, a young chief from Karekare, had been fishing in the bay far below when a rogue wave smashed him against the rocks and dragged him out to sea. Hinerangi mourned for weeks, sitting on the cliffs in grief, looking out across the ocean. And then she simply disappeared. Her spirit went westward, it was said, down the sunset, the golden pathway of Tane, to join her lover, but the cliff face took her image. Ahua means “the appearance” or “the likeness”.

Today, a striking and powerful pou whenua of Hinerangi, carved by local Sunnah Thompson, guards the loop track. It was unveiled in 2011. The following year, a woman disappeared on the track. Another vanished earlier this year. In 2004, a woman had disappeared into the night at Piha. No trace of any of these women, each attractive, lively and young, has ever been found.

The high, sharp edge

To stand on the Mercer Bay cliffs is to be overwhelmed by their height and their terrifying possibilities. They tower 240m above the wild surf, higher than the Sky Tower’s “Skydeck”. You can see 50km and more out over the wide, restless, empty ocean. An ancient volcano once spanned that entire distance, impossibly vast. The Waitakere Ranges are all that remain, just the lower eastern slopes of a beast five times larger than Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe and Tongariro combined, worn down to rock that won’t yield.

Maori legend touched instinctively on this geological truth of the place, Mercer Bay being said to be where Rangitoto originally stood. Tiriwa, the giant whose domain was the ranges, known to Maori as the Great Forest of Tiriwa, became annoyed that the volcano blocked his view. He lifted it from the sea and carried it to where it is now in the Hauraki Gulf. The bay was known as Te Unuhanga o Rangitoto, the removal of Rangitoto.

It was one of the oldest settled areas in the Waitakeres, possibly because it was an imposing natural fortress. Recent archaeology has found a network of caves in the sea cliffs, some four metres across, that would have been linked with platforms and ladders. The local Maori lived inside the cliffs, protected in those ancient violent times of slaughter when no one was safe. Andrew Mercer, a slate maker in early Auckland, later farmed here and gave the bay its European name.

In 1948, the first identification of radio waves with galactic sources was made on these cliffs. They are so high, so well aligned to the west and so open to a broad sea and sky, they were the perfect site for the pioneering Cosmic Noise Expedition. The expedition authenticated the link between radio sources and celestial objects and helped found radio astronomy, which went on to discover the Cosmic Microwave Background, the “relic radiation” from the beginnings of the universe.

The hefty stone with the brass plaque commemorating this extraordinary cosmic connection rests in the car park at the end of Log Race Rd, where you start out on the loop track that runs along the cliffs. This is Hikurangi, “the mount touched by the sun”, equidistant between the black-sand beaches of Karekare and Piha, 300m above them though only 1.6km away from each. The car park was the site of a large military radar station in World War II where my mother was stationed for five years.

The radar vectored lonely aircraft to safe landfall as they flew here from Australia or out of the Pacific. Many American crews, often poor on navigation, were thankful for the guidance of the operators. Some would have missed landfall completely and been lost forever. A marine beacon on the old radar tower still sweeps the sea every night, rotated by the old radar turning gear, warning ships away from the coast.

A place both of hiding and of reaching out, then, and it carries on in different ways. The car park seems always to have a couple of visitors. Locals tell me it’s a busy spot for drug and sex rendezvous. Often there’s traffic through the night as these Piha industries do business. Throughout the day, lone figures park up, looking for a connection of sorts, while elderly mid-week trampers with their cut lunches and binoculars start off to walk the track to Karekare and back. It’s a much-used area.

The fateful track leads off the car park to the right, seaward, and quickly overlooks Piha. The giant sawtooth coastline cuts its way northward before giving on to the long flat blade of Muriwai on the horizon. About 200m down the track is a wooden seat that offers a view of the coast all the way to the Kaipara Heads on a good day. In midwinter, migrating whales can be seen heading south. In summer, dolphins play in the surf. The seat provides a spot for a quick breather.

The track then drops steeply down towards Mercer Bay and the cliffs. It’s breathtakingly beautiful. Now you’re facing south, looking over Mercer Bay towards Karekare, the broad black sands of Whatipu and on to the Manukau Bar. On a fine winter morning, you can see the tip of Mt Taranaki glistening in the distance.

Precipitous height and a scale that makes you insignificant. Wildness and loneliness. Dense bush at your back, the endless ocean before you, there on a narrow line between them that threads the clifftops. The high, sharp edge of the world. In the 1970s, Rick Poynter made pioneering hang-glider flights here, taking his life in his hands.

He told me launching from the cliffs was terrifying.

The rest was easy.

The missing women

Cherie Vousden was a 42-year-old North Shore mother to a young daughter. She often walked or ran the Mercer Bay loop and knew it well. “She loved the sunsets out there,” her brother Darren Roberts told the Herald. “She would come back home with daisies she had picked from Log Race Rd.” Her sister-in-law, Rachel Vousden, told the paper it was Cherie’s “thinking spot, she went there regularly”.

On the evening of Saturday, December 22, 2012, Vousden drove down the long, lonely, loose-metal straight of Log Race Rd and parked her car near to where the loop track begins. A couple saw her at around 7.15pm as she walked south down the track, jandals and a bottle of wine in her hand, perhaps to watch the sun set. Her car was found unlocked and empty a few hours later.

The police made an intensive search for her by land, sea and air in good weather over the following days. The focus was soon exclusively on the water, as they believed she had fallen from the cliffs. Inflatable rescue boats (IRBs) from the local surf clubs were used to search the coast from North Piha to Karekare. The Westpac rescue helicopter joined them.

Vousden’s family were naturally distraught as the official search found nothing and wound down after a few days. They and friends continued looking. “We spent many weeks up there searching,” Roberts told the Herald. They also found nothing. No jandals, no wine bottle, no piece of clothing. Vousden had simply vanished.

“It was absolutely heartbreaking not knowing, and still not knowing”, what happened, Roberts said.

The emotions came flooding back for the family earlier this year, when another woman disappeared in disturbingly similar circumstances.

Kim Bambus was a 21-year-old nurse at Middlemore Hospital. Originally from the Bay of Islands, she had lived in Auckland for four years. Her sister, Storm Bambus, told Stuff Kim was a “tiny little thing and the life of the party” and “very independent”. Like Vousden, Kim Bambus regularly ran the Mercer Bay loop.

On the morning of Friday, March 24, Bambus, dressed in a pink exercise top and black shorts, slipped on a dark-coloured jacket and laced up her Nike running shoes. She tied her hair in a ponytail and grabbed a large water bottle. After leaving her Ponsonby flat, she went shopping at a Countdown on Williamson Ave, buying snacks. The supermarket’s CCTV footage confirms this last known sighting of her.

Bambus had told her flatmates that she was going for a run at Piha. When she didn’t return that evening, with the night falling, they drove the long, snaking route from the city to the beach to try to find her. They reported her missing around 8pm. Her bright-yellow Hyundai Getz was found five hours later in the Log Race Rd car park, close to the start of the loop track, just where Vousden’s car had been found. Her mobile phone was still inside.

Police started a search in darkness, in the bush around Log Race Rd and down the Ahu Ahu track. “There were helicopters all night,” Storm Bambus told the Herald. She had immediately driven down from the Bay of Islands.

Forty police and Land Search and Rescue (LandSAR) personnel were soon committed to the operation, which was hampered by low cloud and rain. Several abseilers searched the cliff face. The police helicopter looked along the coast from the air while local lifeguards did the same from IRBs on the sea. I was among them.

By Sunday, there were drones in the sky, racing up and down the cliff face. Their cameras revealed nothing. Shoreline searches were organised with the locals at Karekare and Piha. Police did letter-drops in both communities. The search for Bambus was intense. Infrared cameras were even used, to tease out small differences in heat sources that can show up a dead body hidden in the dense bush.

Bambus had vanished too. Her disappearance naturally brought comparison with what had happened to Vousden. When Vousden vanished, comparisons had been made to another young woman’s notorious disappearance.

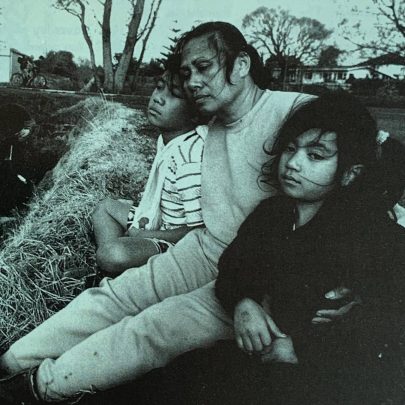

At 9.30pm on Sunday, October 10, 2004, Julia Woodhouse and her teenage son, Henry, were driving back into Piha from Auckland. As they rounded a bend, they were shocked to see a distressed young woman on the road wearing nothing but underwear, Ugg boots and a sweatshirt. Woodhouse stopped the car and asked the woman if she needed help. Her name was Iraena Asher, a 25-year-old trainee teacher and part-time model, and the events that followed made her a household name in New Zealand.

Asher was an intelligent, strong young woman, but she was also bipolar, and affected by alcohol and drugs that night. The later police investigation claimed her behaviour had become increasingly erratic over the previous days. Her family disagreed — both her father and sister had seen her just the day before she disappeared — but it seems likely she was in the grip of a manic episode. She had admitted both missing and doubling up on her mood-stabilising lithium pills in the month prior, and a long-term relationship had ended badly only a week before. Police claimed stress could cause her to relapse into bizarre behaviour.

That Sunday, Asher had gone to a house at Piha with her new boyfriend and another couple. They later testified that she went down to the beach alone at some point and returned soaked to the skin. She refused a change of clothes, they said, and chose to go naked beneath a duvet. Her behaviour became teasingly seductive, they claimed. Her boyfriend later left without her, at her request.

Other people came and went from the house. At around 9pm, Asher called the police, claiming she’d been drugged and was being pressured into having sex. The police called her a taxi, which never turned up. She left the house, going out scarcely dressed into a cold, blustery night, and was shaking and anxious when Woodhouse found her.

Woodhouse took her to the small guesthouse she runs with her partner, Bobbie Carroll: the Black Sands Lodge on Beach Valley Rd. It’s a stylish place with a good reputation. Asher took a shower, and Woodhouse and Carroll gave her tea and a dressing gown and offered her a bed.

They didn’t call the police because of Asher’s negative reaction to the idea. She confided she felt safe, Woodhouse said, but appeared suspicious. Carroll thought she might be coming down off LSD. It is known that she and the others at the house had smoked cannabis that day. At least one person in the house she’d left had taken ecstasy the previous night.

Asher called her ex-boyfriend’s mother instead of the police, then watched television with Henry and said she would stay the night. She would sleep in the lounge, with its French doors that open out onto the garden and the road leading to the Tasman Lookout. A little after one in the morning, minutes after Woodhouse had tucked her into bed, Asher left through the French doors, heading quickly across the lawn, down the road and over the field behind the library. Carroll gave chase, but found only the dressing gown.

Around 1.30am Asher was seen naked beneath the street light near the Piha store by a couple out walking their dog in the middle of a wild, stormy night. It was bitterly cold, 6°C or less, even without the wind chill. The dog walkers were shocked, but did nothing. They hid, and watched the naked woman apparently talk to the street light and kneel and kiss the ground before she walked towards the beach. Asher disappeared into the darkness and was never seen again.

Carroll had, meanwhile, returned to the lodge and called the police, but by the time searching for Asher commenced, around 4am, all clues to her whereabouts had vanished. It was presumed that she walked out into the ocean, but the surf and sea conditions were huge. Waves were four to five metres high and dumping. The water was bitterly cold. The thought of an individual walking into such bone-chilling water is hard to accept.

There isn’t a lifeguard at Piha who believed she went into the water. To use a surf term, nobody could get out the back that night. The shore break was just too huge to get through. A highly experienced surfer failed to get out that evening in the same conditions. Asher would have been thrown back onto the beach, alive or dead.

The following weekend, shoreline searchers and the rescue helicopter combed the rocky pools and headlands northwards, where bodies drift in the current. I did a day’s low flying in the police helicopter hoping that, with the surf dropping to almost flat calm, the body — if it was in the water — would be easy to spot. Searchers climbed Cathedral Cave, and explored the coves all the way to Bethells. Nothing turned up. The search was called off after five days, with nothing to show.

The easy answer

In July 2012, five months before Vousden disappeared, Coroner Peter Ryan ruled that, while Asher “had a lot to live for”, there was “a strong probability that she went into the sea in the early hours of October 11, 2004, and subsequently drowned”. Senior Sergeant Mark Fergus, who led the five-day search for her, agreed with the finding, arguing her body would probably have been found if it was in the bush, and that foul play was unlikely.

I’m convinced, with many locals, that she didn’t go into the water. We’d have found her if she had. Whatever her mental state, I believe Asher was possibly suffering from hypothermia, perhaps since her first soaking from earlier that cold day.

A bizarre aspect of moderate to severe hypothermia is “paradoxical undressing”. Some internal malfunction makes victims feel hot and they remove their clothes, accelerating their decline by heat loss. Hypothermia also makes victims confused, disorientated, irrational. The final stage, often associated with paradoxical undressing, is “terminal burrowing”. Some primitive instinct engages, and victims find some small hiding place where they literally curl up and die.

An extensive search of such hiding places around homes, baches and sheds was made, but it’s possible that Asher’s body will be found, tomorrow or years from now, perhaps not far into the bush. Bodies have been found before at Piha after many years of lying only metres from a track.

Ryan unfairly scapegoated Woodhouse, Carroll and Woodhouse’s son Henry, his report finding that their failure to contact the police on first meeting Asher contributed to her death. They thankfully later cleared their names of this unjustified culpability. The real contributing factor was the slow search and rescue response when police were called after Asher ran from the Black Sands Lodge, where Woodhouse and Carroll had so generously offered her warmth, refuge and help.

When a person goes missing, the call goes to the Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) in Wellington, which handles the response of multiple agencies. The call is assessed, which can take an hour. The police, who exercise complete authority over the operation, then contact New Zealand Search and Rescue, which directs resources to it. More hours are lost, but this is not the worst of it. A veteran of many rescues in the area still feels with deep remorse that the search for Asher was badly handled. Local search and rescue volunteers were left cooling their heels for six hours or more before being allowed to take part in looking for her. The concern of the police in these cases, not unjustified, is that evidence and scents will be trampled. Yet while dogs and other outside resources are brought into the area, often over considerable distances, the chance to quickly find the missing person is lost.

What is needed is immediate action by local search and rescue, the people who can move quickly and who know the sea, the surf, the bush, the tracks. But they cannot move until allowed to by police, and this is immensely frustrating for them. This slow path to providing a local response to people going missing, paved with good intentions as it may be, was also a factor in the searches for Vousden and Bambus.

Adding up

“I’ve been out there every year,” Rachel Vousden told the Herald when Bambus disappeared in similar circumstances to her sister-in-law’s, “and it’s the same as it was. You follow the track. It’s very hard to go off the track — it’s very dense bush.” She reckoned something didn’t add up about the disappearances. “If they are falling into the ocean,” she said of the two missing women, “why is nothing floating up? Why is nothing showing up?”

I agree. I agreed at the time. The Mercer Bay track doesn’t run along the very cliff edge. It’s well graded and not technically difficult, with few places where someone might fall. The few dangerous points are protectively fenced. We also know exactly what happens when someone falls accidentally by carelessly stepping off the track.

On Sunday, September 3, 2006, Fiona Hamilton, a 43-year-old Australian woman, lost her footing above Mercer Bay and fell down the cliff face. This is just what is supposed to have happened to Vousden and Bambus. Hamilton had asked her husband to take a photo of her. She went off the track, stepped backwards too far. She fell 150m down the cliff face and onto a ledge 50m from the sea. She died instantly, but her body was held by the cliffs.

The cliffs may seem vertical when you’re standing on top of them, but they mostly arc out seaward, usually many metres, and they are studded with ledges and sharp outcrops of rock. When the Auckland Line Rescue Team made the difficult recovery of Hamilton’s body, the abseilers had to frequently stop to place protection on their ropes where they rubbed against the sharp rocks.

It takes six or seven seconds for a human body to fall 200m, by which time it’s travelling at more than 200km/h, a fearsome speed. A falling person would almost certainly leave traces of body parts or clothes on the cliff face on the way down. This is the frank reality. It’s not a clean death.

Even if Vousden and Bambus fell clear of the cliffs and into the water, it’s likely that the sea would soon have given up their bodies. Drowning used to be known as “the New Zealand death”. For more than 150 years, we’ve filled our graveyards with drowned settlers, children and shipwreck victims. It’s rare that we don’t find the body. Perhaps they’re not intact, but they do wash up. Victims of drownings at Piha and the notorious Te Henga fishing rocks are usually found a few days later, up the coast at Muriwai.

The bush also often gives up its dead, eventually. An archaeologist once picked up an unusual-looking rock as he walked down the Ahu Ahu track, part of the Mercer Bay loop. He realised it was a human skull, discoloured and moss-covered. A quick search above the grizzly find revealed the remains of an amateur botanist, who vanished seven years earlier on a fern-gathering expedition.

This isn’t to say Vousden and Bambus didn’t fall into the sea without a trace, but these are serious points against the scenario, and especially against it happening twice in just five years.

Police have kept an open mind about what happened, not ruling out foul play, but without a trace of the women, there is nothing to follow except that long fall into the sea. The Waitakere police are heavily committed, their reduced numbers covering a wide area that reaches all the way to Rodney. The rise of domestic violence, burglary, car theft and so on puts great pressure on them. With all the best intentions in the world, a disappearance with dwindling answers demands a resolution. It’s offered perhaps too easily by the high cliffs of Mercer Bay and the fearsome surf of the west coast.

The coroner considered it likely that Vousden drowned. I’m concerned that it might be an easy answer, especially in the light of Bambus’s very similar disappearance. When Vousden vanished, the locals along Te Ahu Ahu Rd, which connects Log Race Rd to Piha Rd, asked the council and the police to consider closed-circuit surveillance in the car park. They had noticed the rising number of cars with solo drivers.

A local resident, who didn’t wish to be named, told me the car park was a hang-out for “sick people, lonely, sad losers. They park up there for hours. You can’t walk up there without being watched. I keep thinking, what goes?”

The dark other

As with all small communities, at Piha there is a dark other, an underbelly of crime, loneliness and malevolent behaviour, people who do things dark and tragic. Piha had a notorious drug industry at the time Asher disappeared. It’s possible she could have been a victim of it one way or another, even if just hit by a car driven by someone who wanted nothing to do with the police. Either injured or killed, she would probably have been immediately transported from the area. We’ll never know. The roads at Lone Kauri and Waiatarua were not closed off the night she went missing. Another failure of response.

Asher’s disappearance is almost certainly unconnected to the vanishings of Vousden and Bambus, but it shows how easy it is to offer that wide sea as an answer when there are no clues. And it shows how critical an immediate response from experienced local search and rescue operators is to the finding of a missing person.

These days, I walk the cliffs looking for clues to what happened to Vousden and Bambus, but there simply are none. Every turning on the cliff and the tracks has been so well covered that other, darker possibilities must be considered in their disappearances. I’m not alone in thinking this way. As Vousden’s brother told the Herald when Bambus went missing, “There’s always that thought of other scenarios.”

In just five years, two young women have gone missing in the same place, in the same way. My feeling is these women completed what they had set out to do on the days they vanished. Walk, run, get into nature, feel life breathed into them by the exhilarating coast, find peace in the roaring west wind. They did that and went back to the car park. Vousden’s unlocked car could be read as carelessness, or as an indication that she returned to her vehicle. To me it was the car park and not the cliffs where their lives came into jeopardy.

Like Asher, Vousden and Bambus both had a lot to live for. They both knew the Mercer Bay loop well and were unlikely to slip and fall by carelessness. They were evidently surrounded by family and friends who cared for them, who paid attention to them and their lives. These people all considered their disappearances didn’t make sense.

I hope some sign of what happened to Vousden and Bambus — and to Asher — will appear, even if it is their bodily remains. We all know the emptiness of losing someone close to us, but add to that the unbearable ache of not knowing just what happened to them. It must be difficult to bear, a mental wound that can never heal.

My concern is that more such wounds will be inflicted. I’m troubled by the thought of an abductor of young, vulnerable women at Mercer Bay.

People just don’t vanish into thin air, except in myth.

This is published in the November- December 2017 issue of Metro.