Mar 17, 2015 Crime

Auckland engineer Paul Ellis was found not guilty by reason of insanity of the baseball-bat murder of his father, Tony, in 2001. Today, Ellis tells the story of his descent into madness and the long years of recovery. It is a story of hope and despair, inspiration and insight but, above all, remarkable courage.

There is only one thing worse than losing your mind, says Paul Ellis, and that is finding it again.

Madness is a seductive and irresistible mistress. Madness made him kill his father. Madness took away the pain. More than that, the madness made it right.

But when the madness is gone, what is left?

For Paul Ellis, who was locked up in Auckland’s high-security Mason Clinic for the criminally insane, there was only loss. “I had lost my father, my freedom and my mind. I couldn’t have got any lower.’’

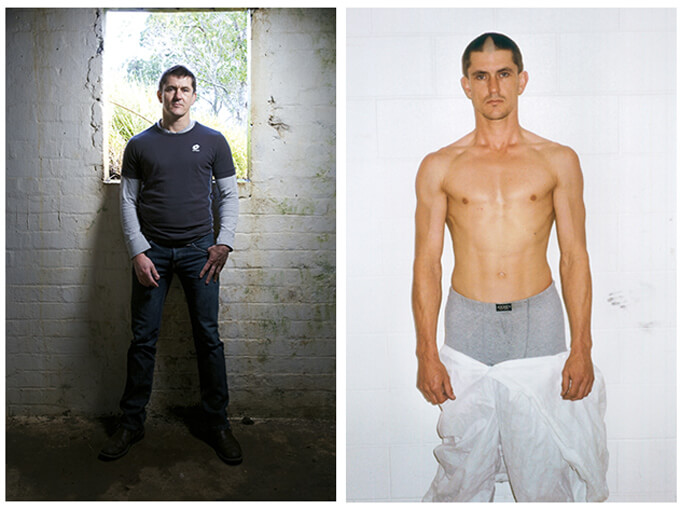

And yet today, Ellis, 43, works full-time as an engineer at a Penrose company, exercises daily at the gym and lives with the woman with whom he wants to grow old. Sanity prevails.

Ellis has never spoken publicly of his ordeal. He is sharing his story with Metro to give hope to others in a similar situation and to provide insights that may challenge the misconceptions which stigmatise the mentally ill.

What happened to him could happen to anyone, he believes. “Insanity is within everybody’s reach.’’

Dr Sandy Simpson, the psychiatrist who supervised his care at the Mason Clinic and now its head, says Ellis’s story will give hope, “and hope is crucial — the sense that people can turn their lives around and recover from the horror of this stuff. I take my hat off to Paul for the courage of talking about it.’’

Simpson says one of the most moving aspects of his clinical life is working with people like Ellis who are recovering from having killed because of their mental illness. He has “immense respect” for what they have to deal with.

“Watching people face families and the people they have harmed, with remorse, with grace, with dignity, is stunning to watch. It is when you see that happening that you know they are rebuilding a personhood that will last. That’s when you know that all the rehab, all the talking, has allowed them to be restored again as people and that’s humbling to watch.’’

Paul Ellis remembers the night he drove 90 minutes from Maraetai to Kaukapakapa, to kill his father Tony, on October 25, 2001.

“I was chillingly calm. It was very strange. It was like I knew something was going to happen but you just can’t stop it happening. It felt like I was just an actor playing the part; that it wasn’t me doing it.

“I really thought he was going to be compliant with what I wanted, that he was going to let me have the gun and shoot him. I thought it was either him or me and it would stop the madness.

“I knocked at the door. He came to the ranchslider door; opened it up. I think he was kind of surprised; it was late at night, maybe 11 or 12 o’clock. I had gone that day and got my bizarre haircut with a strip shaved up the middle to uninhibit my third eye… I just said, ‘I’m here and I’m going to kill you.’ I don’t think he believed me at the time. He didn’t think I would, you know. I got the strange idea in my head that my father had killed his father and I had to kill him as well. Because he didn’t ever talk about his father or his family. That’s madness for you.

“He told me to wait there. He shut the ranchslider. I think he locked it and left me outside. He got on the phone to ring the police. The back door was unlocked and I walked in. He kind of told me he’d rung someone to get help. He didn’t hang up the phone.’’

The 111 call records Ellis telling his father to shoot him. “I’m not going to shoot you, Paul. That would be the last thing I would do. What would I want to shoot you for?’’

His son replies: “It’s either you or me. Go get your gun. It’s either you or me.’’

Ellis says his father returned to the lounge with a baseball bat. “I convinced him to put down the baseball bat and I picked it up. I was just holding it, you know. He said to me, ‘Who’s going to look after your mother?’

“My father had a dog, an English pitbull, and he kept it in the garage. I remember when I picked up the bat off the settee he went and opened the ranchslider door. I knew at the time why he was doing it, because when he opened that door up the dog would always come out of the garage. But it never came out.’’

The 111 tape then records screams and a banging noise. In the silence that followed, there is the sound of a metal baseball bat falling to the floor.

He was still standing over the body of his dying father when the police arrived a couple of minutes later.

It was, said Crown prosecutor Simon Moore at Ellis’s trial a year later, a “true Greek tragedy’’.

So how did it come to this? How did this Oxford-born boy, the second of three sons of an unremarkable, loving middle-class couple, become a psychotic killer?

There was certainly no sign of trouble when the Ellis family moved to New Zealand from England when Paul was 15, doing his fifth-form year at Howick College. But he acknowledges he wasn’t getting on well with his dad when he left home and went flatting at 17. It was then he was introduced to cannabis and quickly developed a $150-a-week habit, smoking every night, and even when he woke in the morning.

“By nature, I’m quite excessive.’’

Being frequently stoned didn’t stop him holding down a well-paid toolmaking job at Fisher & Paykel, and buying his first home, a rundown bach at Maraetai, at 23.

He dabbled in other drugs, but dope was always his first choice and, in those early days, it didn’t seem to be doing him harm. Handsome, athletic and intelligent, he had no problems attracting women, and his relationships usually lasted several years.

Today Ellis describes his 20-year-old self as “troubled’’ but says, “I was never the type to go out and cause anyone else any trouble. I always had good morals. But the darker side of things always interested me.’’ In music, he liked the Doors, and Stone Temple Pilots and their drug-addicted frontman Scott Weiland. In books, he enjoyed the writings of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and his exploration of nihilism and atheism.

He doesn’t think the music and reading tipped him into madness. “Music is always going to be something people will relate to, no matter what you’re feeling. It’s just a form of expression. It’s art.’’

At 27, after 10 years of heavy cannabis use, Ellis had his first psychotic episode, but had no idea that what was happening to him was a mental illness. Others probably thought he was having a “strange turn’’, he says, or a nervous breakdown. And it was a gradual process. “You don’t just wake up one day and you’re fully blown mad. You become mad slowly, slowly.

“I had reached the point where I had pretty much burnt myself out. I’d just finished a relationship so I was going to work and coming home and spending time by myself. I ended up not really having anyone to talk to and it became a pretty lonely existence.

“I had physical symptoms. I was sick, I had diarrhoea. I don’t know if it was my body saying, ‘I’ve had enough.’ That kind of lifestyle is pretty unhealthy no matter how you look at it. Any addiction that starts to take over your life, starts pretty much to drag it down.

“I started to notice most things in my life — relationships with people, my work, my family — all started to become neglected, apart from my addiction. And I think that’s how addictions go; it takes over. I spent more time by myself with my drugs. I started to notice something wasn’t right with me. There was a change in my thinking. I started to fall into paranoia.’’

He attributed his physical illness to the fact someone had come into his house and poisoned his coffee. He became convinced he was being watched. “I couldn’t understand why that could be at first. I spent a long time trying to find out what the answer was and in the end I had to create my own answer.’’

“My delusion was wrapped up in Nietzsche’s philosophy. His concept was that looking back through history, certain men stood out. One would have been Jesus, another Napoleon Bonaparte.”

His paranoia, he recalls, was on a grand scale. “My delusion was wrapped up in Nietzsche’s philosophy. His concept was that, looking back through history, certain men stood out. One would have been Jesus, another Napoleon Bonaparte. He recognised there would be other such übermensch, or what’s been translated as ‘supermen’, in the future. He described man as not being the end result, that man was a bridge over the abyss, a gateway to something better and would probably evolve another step. I thought I was one of Nietzsche’s übermensch. That’s why it’s seductive. They call it delusions of grandeur, where you think you’re going to be something very powerful.’’

Those delusions “bounced around’’ with the feelings of persecution and fear. “You become hypersensitive to stuff that others would consider of no consequence. You see a message in a dead bird on the road, or an advertisement, or something on the radio, some song. When you become mad, it has some kind of meaning.’’

Ellis became convinced that others were trying to drive him to kill himself. “Obviously there were moments where I thought that may be the best thing, but I felt people were making me do it rather than wanting to do it myself and I was fighting it, fighting it.’’

While it is likely his cannabis use triggered the psychosis to which he was already genetically and biologically predisposed, Ellis didn’t imagine he had a mental illness. He did, however, decide the drug probably wasn’t doing him much good, and stopped taking it.

After seven or eight months, the psychosis “burned itself out’’ — a return to normality that most attributed to him giving up drugs. But as soon as he became well again, he returned to cannabis.

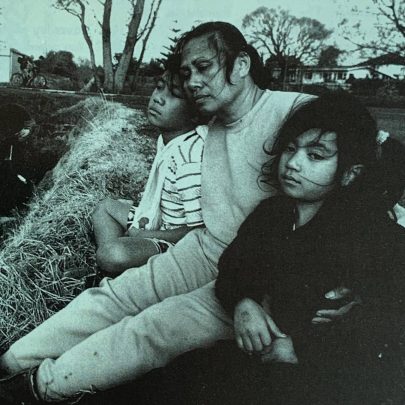

By the time of his second psychosis at 35, Ellis had met and married Debra. The couple had one child and she was pregnant with a second. This time, when the madness took over it did not let go.

“It was pretty much déjà vu. I think I didn’t want to believe it was going to happen again. It’s extremely difficult to face the fact that mentally there is something wrong with you.’’

There were stresses which might have triggered it, he says. There was tension in his marriage and he was under pressure at work. “In the end, I think I could have worked through all those things like most families have to, if it wasn’t for the cannabis.

“Looking back, my life was a mess. It was a recipe for disaster, and a disaster it ended up.’’

The sense of persecution returned, as did the delusions of grandeur. There were auditory, bodily and visual hallucinations. He heard the devil laughing at him, saw the Pope, saw grossly disfigured people walk by with limbs missing — and wondered why no one else noticed. He woke up to what felt like electricity coursing through his body and tried to scream but could not. “It frightened me — I thought something had entered my body.’’

He spoke to his manager at work about it — “After that he started to think something wasn’t quite right with me.’’ The manager tried to arrange a medical appointment, but Ellis was so paranoid he trusted no one. “I thought my spirit was metamorphosing and I came to the conclusion that this happened to everyone and that this was part of something that happened to you but nobody spoke about it.’’

Debra, alarmed by his behaviour, told Ellis’s parents that Paul was using cannabis again. His father fired off an email saying how disappointed he was. Once again, about three months before the killing, Paul stopped using. “I decided I had to make some changes in my life and I knew the major thing which was destroying it for me was my cannabis use.’’

He stopped sleeping and ate little. His weight dropped nearly 20kg to 69kg.

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, were simply confirmation in his mind that the world was crazy — not him. On September 12, he attended the birth of his second child but Debra had already left him and was living with her parents.

In early October, Tony Ellis — an engineer like his son — became so concerned about Paul’s behaviour that he called Counties Manukau Health’s community assessment and treatment team and asked for him to be committed. Paul says he “told them to get lost’’.

His madness raged unabated. There were messages in car number plates. After seeing NØ183 while driving, he stopped at number 183 Whitford Rd and talked to the occupant. The plate “KITTY’’ told him he had to return the cat to Debra. By this time he was dumping her belongings in her parents’ drive.

Ellis remembers the police arriving in the early hours of October 12. “They came to take me away; all I had on I think was a towel but they wouldn’t let me go inside and grab my clothes or anything. I was kind of quite surprised I was getting carried away by the police.’’

He didn’t fight back. “If you end up in a police car getting taken away to a psychiatric hospital you try to be on your best behaviour, don’t you?’’

He was admitted to Counties Manukau District Health Board’s Tiaho Mai mental health unit at 2am. “They stuck me in a room, and gave me a couple of sleeping pills.’’

The psychiatric registrar who admitted him believed Ellis needed to be detained under the Mental Health Act as a significant risk to himself and others. Ellis said he wanted a judge to review his committal and, at 11am, a family court judge heard his application and allowed Ellis to go, despite the fact Ellis had not been thoroughly assessed. Reports at the time said Ellis was “calm and collected and answered eloquently when a series of questions were put to him’’. In retrospect, Ellis doubts he was that eloquent.

He was sent home with a prescription for the anti-psychotic drug Risperidone but the dose was too low to be effective. His father, stunned by the decision to release him, wrote to the psychiatrist saying he would hold him personally responsible for any “unfortunate’’ outcome.

Six days after walking out of Tiaho Mai, Ellis resigned from Fisher & Paykel after 18 years’ employment. Within the week, he had received the sign to kill. It was a number plate starting JM, which reminded him of Jim Morrison, and the Doors song The End, containing the lyrics, “Father, I want to kill you.’’

Just after 10pm on Friday, October 25, 2001, he set off on his fatal drive to Kaukapakapa, determined to end the madness.

Ellis arrived at the Mason Clinic, in the grounds of Auckland’s old Oakley and Carrington hospitals, in the back of a Chubb armoured wagon. When the iron gate clanged closed behind him and the guards buzzed him through, “I was still under the impression there was some mistake. I was still thinking that this big conspiracy was bigger than the Mason Clinic and I wasn’t going to be in there for too long.’’

Perth-based Clive Ellis saw his brother a few days after the killing. “I couldn’t believe it. It was like a horror movie, but it was worse because it was real. You could not believe someone could look so horrible and evil. Just to look at him with his head shaven… and his eyes had no colour in them. The eyes were the thing — there was absolutely no emotion in those eyes. He was saying over and over, ‘I had to do it, you don’t know what I know, I’ll be out of here in a couple of days, you have no idea what it was like.’ I nearly punched him. I just stood up and said, ‘I’m walking out of here.’’’

But Clive did not abandon him, visiting daily until he had to return to Australia a few weeks later, and flying back and forth numerous times to support him, take control of his financial affairs and to help Debra.

About four to six weeks later, as the anti-psychotics began to take effect, the paranoia and delusions faded. The enormity of what he had done hit home.

“I started to realise what I’d done, how long I was going to be in there… and the losses. The loss of my father, the loss of my freedom, losing my mind, the loss of trust.”

Says Sandy Simpson: “Take the delusions and hallucinations away and you take away the justification — ‘I was right to do that.’ You no longer have that defence and because most psychotic violence is against people one knows or in one’s intimate family, suddenly you are faced not only with the horror of having killed, but the horror of having killed someone you loved. That is an immense emotional and existential challenge. You have to be with people while they acknowledge that and be aware the emotional impact is huge and doesn’t go away in a hurry. Most people have an immense sense of self-blame.’’

It made Ellis suicidal. “Coming out [of psychosis] is the worst part, to be honest with you. That’s when it really hits you, that, you know, you’ve obviously made a huge mistake. Going into it, it’s very different, kind of seductive. When the medication was starting to work on me, I started to realise what I’d done, how long I was going to be in there… and the losses. The loss of my father, the loss of my freedom, losing my mind, the loss of trust. All those things come and hit you. If I’d had the means to kill myself, I probably would have. It was the only thing that brought me some kind of solace.’’

The nurse-patient ratio wouldn’t allow such a thing — there was anything from one to four staffers per patient. “They’d lock you up at night but every five minutes shine a torch on you. I remember thinking I couldn’t get any lower than this.’’

When his mother Victoria came, he broke down and wept. “She said she forgave me. She knew I’d lost hope.’’

Victoria Ellis, who had been in Perth visiting Clive’s new baby when her husband was killed, says forgiveness came easily. “The first day I saw him, about three weeks later, he was on suicide watch. I just held his hands and we just cried for about half an hour. I knew he wasn’t an evil person. I knew he was a really nice person.’’

She said it was a shock to realise her son had schizophrenia — both she and her husband had thought his condition was caused purely by his drug-taking.

Those early days of treatment, says Simpson, are all about “structure and de-escalation’’. It is a risky time for all concerned, with patients who are acutely unwell and likely to misread the well-intentioned motivations of everybody around them.

Ellis recalls he wasn’t even allowed to put toothpaste on a toothbrush in those early days.

Calming the patient is a vital first step. “There is nothing too noisy, nothing too fast, and nothing too racy,” says Simpson. “It’s about quietly and calmly explaining to the person what’s going on, talking through with them what their experiences are as much as they are able to, and gradually allowing them space to open up.’’

Ellis was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. A syndrome rather than a disease in itself, schizophrenia can describe a large number of signs and symptoms. It usually manifests around puberty. Says Simpson: “The message we give is it’s your illness that is dangerous, not you as a person, but you are responsible for making sure you don’t allow yourself to drop out of treatment or go back on drugs or fail to take your medication.’’

From the time his psychosis lifted, Ellis was determined to get well. “I wanted more therapy than they gave. They tried to build my hope back up. In the beginning they told me my path through the system was going to be a lot quicker than it actually was which made things a bit easier. It wasn’t the truth but it was what I wanted to hear.’’

His weight ballooned to 96kg and he began going to the clinic’s sparsely equipped gym. “I didn’t feel like working out, I felt terrible.’’ But the habit he formed there remains.

He admits he did not feel safe in the clinic. Sometimes he was threatened; he saw others being attacked.

Gradually, “your identity goes; they take that away from you. They try to make sure you never end up going back there so they try to strip you and rebuild you. You are grilled about your imperfections. They made me realise there were quite a few things wrong — I was severely flawed. I was pretty broken physically and mentally and I pretty much did that to myself. Yes, the mental health system let me down but in the end I can’t blame everything on them. Yes, they let me down, but in the end I did what I did to myself.’’

After three years, he was allowed out to work two days a week and in 2007 he was hired by Murray Watt, then owner of an engineering company in Penrose, working full-time but returning to the Mason Clinic every night.

“I knew the risks,’’ says Watt. “I didn’t tell anyone about his background, not senior staff, not even my wife. I took the responsibility and I just thought it was between me and Paul.’’

Though Watt has since sold the company, Ellis remains there today. He says Ellis was a popular, trustworthy and reliable member of staff. “He is a very good engineer. It’s always nice when you give someone an opportunity and they take it.’’

“I’m accountable for what I did and in the end I have to carry that.’’

In 2004, Ellis asked his wife Debra for a divorce, despite the fact she regularly visited him and wanted him back after his release. Brother Clive describes the decision as “quite selfish’’.

“I just thought for the first time in his life he was so-called well and that’s the time he decides to leave his wife and kids. I just thought the woman has done a brilliant job, brought up two kids, copped a heap of grief, married to a bloke who must have been an absolute nightmare to be married to.’’

“Maybe I am selfish,’’ Ellis admits, “but we weren’t compatible and it was only going to be worse if I’d dragged it out longer. It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was the right decision.’’

A few months after his release in April last year, Ellis met accountancy student Joy Yao at the gym and asked her out — knowing that if the relationship was to become serious, he would have to quickly front up about his past. He told her everything on the third date. “I was pretty much shocked,’’ she says. “Obviously it wasn’t a nice thing.’’

She says while it’s hard to believe the calm, mild man she now lives with could ever have been violent, she’ll be the first on the phone if she notices any changes. “I don’t worry about him, but I will keep my eyes on him!’’ she laughs.

One of the Mason Clinic’s strongest messages is teaching patients to recognise the early warning signs of deterioration. In Ellis’s case, they are loss of interest in things he’s usually keen on, loss of appetite, lack of sleep, becoming aloof and manic. He is drug and alcohol free, but takes enough anti-psychotics to “sedate a horse’’, and sees a community mental health nurse every week.

Ellis says while the mental health system failed him, it’s not in his best interests to blame others. “The only thing that’s going to help me now is to make sure the same thing doesn’t happen again and the best way to do that is for me to take accountability for my actions. Mistakes are inevitable in their line of work, and when they make a mistake sometimes it can be a tragedy like what happened to my family, but there are a lot of successes you don’t hear about. I’m not asking for sympathy or forgiveness or attention. I’m accountable for what I did and in the end I have to carry that.

“My past is very different from the way I live now. In life, for people to change, it’s a pretty difficult thing. It doesn’t happen easily and, for me anyway, I think I needed an adversity in my life for it to happen.

“Unfortunately, it came at a high price — I lost my father and my mother lost her husband. But maybe if he saw me now, he’d be proud of me. I’d like to think he would be. I just wish he was here to see it.’’

By Reason of Insanity

Of about 70-80 homicides in New Zealand each year, an average of four are associated with mental illness, and only one or two of those are, like Paul Ellis, found not guilty by reason of insanity.

In these cases, says Mason Clinic head Dr Sandy Simpson, their actions have been morally driven by the illness. “They feel it is the right thing to do; the only thing they can do is to act according to the demands of the delusions or hallucinations.

“It is the moral drivenness, the moral importance… ‘It is vital that I kill this person because they are going to spread evil in the world and the world is going to come to an end,’ or ‘I must relieve this person of suffering because they are suffering horrendously,’ or ‘I’m under mortal attack from someone else and only one of us can survive and I must defend myself.’’’

The legal definition of insanity is not that people don’t know the moral wrongfulness of their actions, he says, but that they feel a moral imperative to act in that way — a way they find morally repugnant once they are well.

The person spaced out on P does not qualify for the insanity defence, says Simpson, because their culpability began when they took the drug.

The most common misconception about mentally ill killers, says Simpson, is that people believe they have some kind of hair trigger and it’s impossible to predict when they might do something dangerous.

“The pattern of risk is usually very readily under¬stood and, if you take care and time, they can be readily managed. Such people then are at vastly lower risk of reoffending than someone who has done the same thing who is not mentally ill. As a population they are much less risky because the causes of their offending are understandable, treatable and monitorable.’’

Heavy cannabis use is thought to trigger schizophrenia in 5 per cent of predisposed individuals, says the Director-General of Mental Health, Dr David Chaplow, a former head of the Mason Clinic. The number of schizophrenics who kill is “very, very tiny’’.

Committal as a special patient under the Mental Health Act means only the Director-General of Health can approve leave from secure detention, and only the minister can approve long leave. After two or more years of successfully living in the community, a special patient can be discharged and dealt with under a normal compulsory treatment order — meaning they can still be recalled at any time if necessary. “The level of wellness to cease to be a special patient is very high,’’ says Simpson.

The Cull Inquiry

In 2003, an inquiry by Helen Cull, QC, found a series of inadequacies with Counties Manukau District Health Board’s care of Paul Ellis, saying he was released from Tiaho Mai in a hearing that was both rushed and ill-informed. She referred to the “Swiss cheese’’ model of system accidents in which successive holes in the layers of defences, barriers and safeguards line up. “There were numerous holes in the service which ultimately failed Paul Ellis and his family,’’ Cull said.

In 2004, Ellis sued mental health authorities for $180,000 — the first time a psychiatric patient had taken such action over the fatal consequences of a hospital’s inadequate care. While the High Court struck out the case, Counties Manukau Health later made a confidential payment in return for Ellis abandoning his appeal against the decision.

His lawyer Antonia Fisher says the Ellis case was an unnecessary tragedy. “He was a very bright, intuitive young man and his care went terribly wrong. He had a treatable illness that was not treated properly. Paul has been to hell and back.’’

Fisher says that when the judge released Ellis from Tiaho Mai it affirmed for Ellis that he wasn’t insane and other people had the problem, not him.

The Ellises were a devoted family and the support Paul’s brother Clive and his mother gave in the circumstances was extraordinary, with Clive returning from Australia to do much of the investigation work before the Cull inquiry. He told Metro: “I didn’t want the old man’s death to be in vain.’’

Photos by Adrian Malloch.

was first published in the September 2009 issue of Metro. Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the weekly e-mail