Aug 16, 2014 Crime

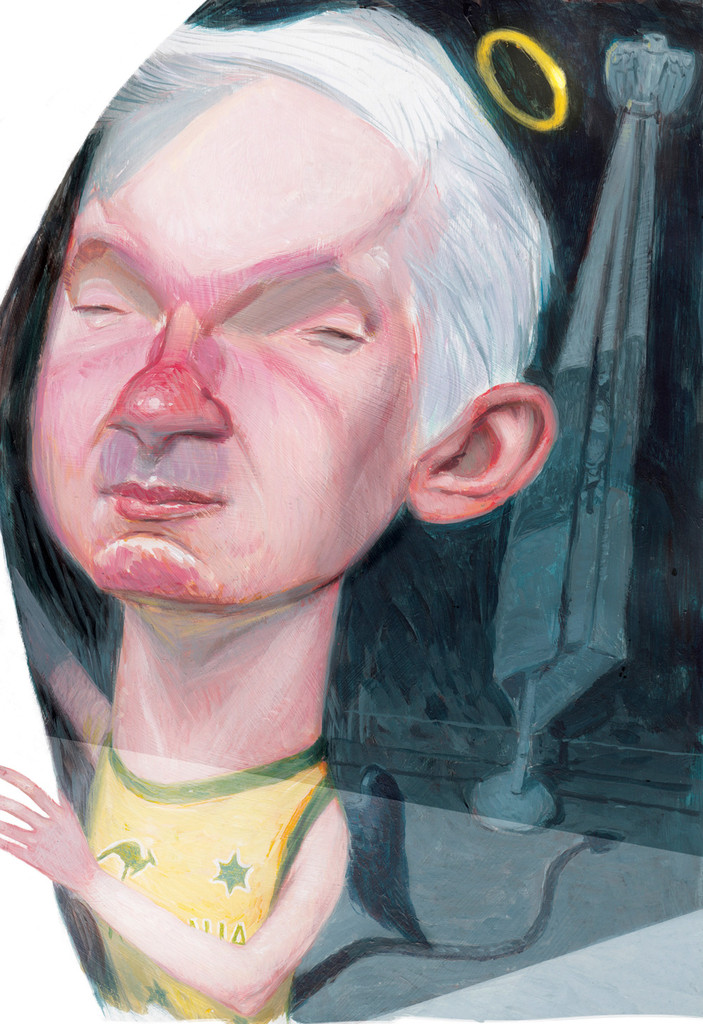

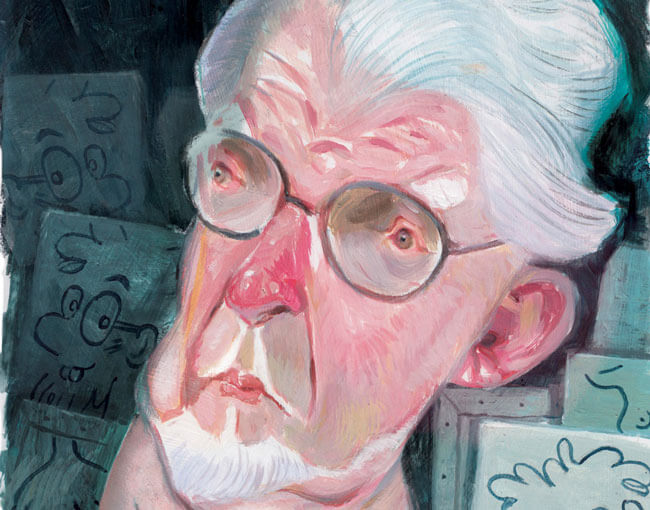

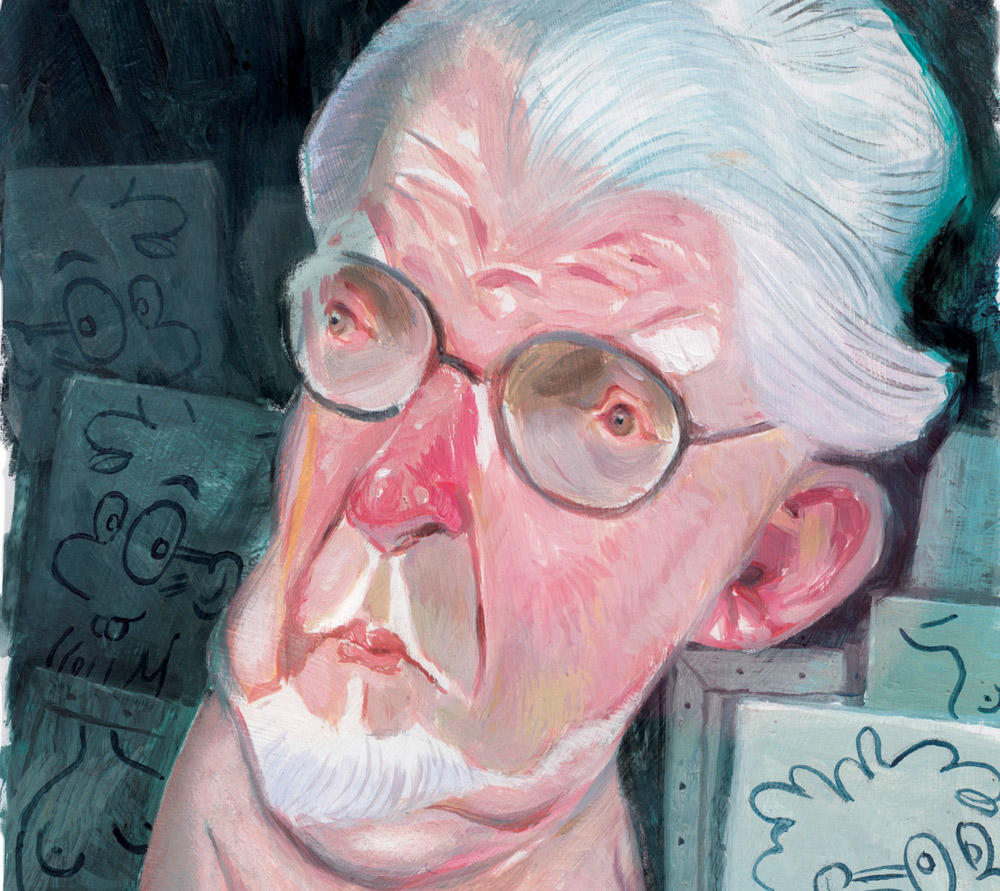

Our foreign correspondent reports from the London trial of Australian entertainer Rolf Harris, and pays homage at the Ecuadorian embassy in Knightsbridge to Australian activist, journalist, spy, menace, wanted man, genius, hero and prisoner Julian Assange.

Published in Metro, July 2014.

Illustrations by Daron Parton.

An old man with white hair sat by himself in a glass cage. He was dressed in a blue suit. He stood up. He wore his pants high around his waist; he was trim, dapper, with pink skin and a thin mouth. He walked to the door. He tried the door handle. It was locked. He bowed his head, and stood there, trapped, nowhere to go, an exhibit for everyone to see in the upstairs courtroom at Southwark Crown Court, a large, unpleasant fortress beside the Thames, near London Bridge.

It was a Wednesday in May, a damp summer’s morning, five to 10. Another day in one of the last weeks of the trial and shaming of Rolf Harris was about to begin. He walked back to his seat. He sat down. The glass cage, the eyes watching his hopeless little journey to the door and back, the small, blonde prosecutor Sasha Wass (“Cool as ice”, The Times) all set to stab him and stab him and stab him with her latest accusations — Rolf Harris, 84, in hell, in public.

I got the last vacant seat in the courtroom. The press were opposite, laughing and much better dressed than the spectators, who wore raincoats, corduroy, big woolly jumpers. One old character changed into a pair of slippers.

The two men next to me struck up a conversation. “Never smoked or drank in my life,” said the older man, about 70, who was in superb physical shape.

“A drink’s all right,” said his neighbour, who rested his hands on his large stomach.

They fell silent.

“What’s in there, then?” asked the younger man, pointing at the plastic bag the teetotaller took out of his raincoat pocket.

“A hat.”

“A hat?”

“A wet hat.”

“This rain.”

“Terrible.”

“All stand,” said the court clerk. The judge entered. Harris was released from his glass cage and led to the witness box. It was his second day on the stand. He was accused of 12 counts of indecently assaulting four under-age girls in the UK between 1968 and 1986 — there were also similar allegations involving two girls in New Zealand. The court would hear about that, in particular about a day in Hamilton; it would also hear about a day at the beach in Australia.

New Zealand and Australia, like remote, bright backdrops to the miserable business of Harris in court. Across town, at King’s College London on The Strand, was the first New Zealand-Australia Festival of Literature ever staged in London. The forlorn hope was that New Zealand and Australian writers might attract a new market of English readers, but the three-day event played to small audiences of expatriates and an estimated three people who were actually English. I was a guest speaker. I enjoyed myself tremendously. But it was such small beer, and the truly spectacular — and more popular — festival of antipodean culture was at the packed upstairs courtroom, near the splashing Thames.

Harris, the Australian made good in England; Harris, a national treasure with his paintbrushes and his extra leg; Harris, harmless and asexual, chortling and whimsical, the light entertainer who had actually operated in darkness. Now, in court, was his Rick Rubin moment. Rubin produced the last, great records by Johnny Cash, turning his songs into high gothic. He had done the same with Neil Diamond. Harris, though, went further. His life was turned into high gothic, and the producer was the merciless Sasha Wass.

She said, “You’re pretty good, Mr Harris, aren’t you, at disguising the dark side of your character.”

“Yes,” he said. His voice was quiet and hoarse.

She said, “This case is about whether, under your friendly and loveable exterior, there is a dark side lurking. You know that, don’t you?”

The old, thin voice gasped, “I suppose so.”

It was his standard response: “I suppose so.” It aimed for diffidence, but it didn’t quite get there; it was weak, lacking, kind of shifty.

Much was made of a holiday to Australia in the 1970s. Harris travelled with his wife, their daughter Bindi, and Bindi’s best friend. The girls were 13. They went to the beach. Bindi’s friend had a swim, and came out of the water. She was wearing a flesh-coloured bikini. Harris came towards her with a towel. He put it around her. Also, according to Wass, he molested her.

A photo of the girl wearing the bikini was produced in court. Harris studied it. Wass said he had complimented her, told her that she looked “lovely”.

“Do you accept that when a man tells a woman or a girl they look lovely in a bikini, they are not actually admiring the clothing, they admiring the person’s body?”

“Possibly.”

“You weren’t talking about the bikini,” Wass said. “You didn’t mean the fabric. There’s not much of it. What you were saying was, ‘You have a great body.’”

The low gasp: “I suppose so.”

“You suppose so.”

“I suppose so, yes.”

“To a 13-year-old. ‘You have a great body.’ That’s what you were telling a 13-year-old.”

“I suppose so…”

He denied there was any touching. Wass kept at it. She held out her hand, palm up. She said, “You digitally penetrated her.”

“That didn’t happen.”

Her hand stayed where it was. “She says you put your hand inside her bikini pants, and digitally penetrated her.”

“No.”

She continued to hold out her hand as she confronted Harris a third time, but this time she moved her middle fingers, thrust them forward, and said, “You fingered her.”

“No.”

The obscene hand stayed where it was. Harris looked away. He started talking about how he wouldn’t have gone to her with a towel, that he didn’t spend much time at the beach, that he didn’t even like the beach. Photos were produced of the beach. You could see bright blue skies, golden sand, a jetty stretching out to sea — you could see all the beauty of Australia, the lucky country, its sun and surf and glowing light.

Another wildly successful expatriate, Clive James, talked about that light when he spoke at the Australia-New Zealand festival on The Strand. James was giving what was billed as his farewell performance. He has leukaemia. He played to a full crowd who cheered and wept for the great prose stylist in his final hour of memoir, gags and poetry. He said he was too unwell to return to Australia. It was a profound regret. He longed to see it one more time, to “bask in the light I never left behind”.

But Harris didn’t want to know about the light. He was a creature of shadows. “I hate sunbathing… I hate the sea… I don’t like the beach.”

His great distaste for spending any time there ruled out any possibility of molesting schoolgirls. Wass ignored the logic of his argument, and said to the jury, “He would do this whether or not there were family members nearby. You will hear other instances in this case where Mr Harris touched children and women alike in quite brazen circumstances. Maybe that was part of the excitement for him, knowing that he could get away with it.”

Harris, said Wass, was “a sinister pervert”. The old man with white hair would have envied James, his compatriot and near contemporary, not only because he was playing on the other side of the river to an audience who loved him. James was merely dying. Harris was being shamed in full view of the media.

The press sat in rows behind his wife and daughter. I approached Alwen Harris during an adjournment. The old dear was led to a ripped orange vinyl couch in a kind of lounge outside the courtroom. She was left alone. I thought she could do with a friendly voice. I went over to her and said, “I’m from New Zealand. Just wanted to say hi. Hang in there.”

She looked up and smiled. She was very frail. She didn’t seem quite all there.

Another Australian accused of serious sex crimes, half Harris’s age, was also more or less walking to the door and then sitting back down again in a cage in London.

Another Australian accused of serious sex crimes, half Harris’s age, was also more or less walking to the door and then sitting back down again in a cage in London.

I went to the Ecuadorian embassy in Knightsbridge to pay silent tribute to the extraordinary Julian Assange, 42, who has elected to hide inside a converted women’s bathroom. He has political asylum in the embassy. He owns a table, chairs, treadmill (a gift from film director Ken Loach), laptop, phones, and “safety equipment he keeps close to his bed”, according to the Daily Mail.

He told the paper, “Of course it’s difficult to wake up and see the same walls, but on the other hand I am doing good work… While I’m imprisoned here, there’s a developing prison where you’re living as well.”

The theme and point of his WikiLeaks work is freedom of information. But that right was supposedly taken away from Assange in a strange sub-plot to the Australia-New Zealand literary event.

The first I heard about it was when Steve Kilgallon rang from the Sunday Star-Times in Auckland. He said, “What do you know about the New Zealand High Commission getting Julian Assange banned from speaking at the festival?” It was a thrilling question. I said I’d ask around.

He called on Saturday morning. I’d made my pilgrimage to the Ecuadorian embassy the previous day. I thought: wouldn’t it be fantastic if Assange appeared at a window and waved or something? I was a fan, an admirer. But when I looked into the claims of his expulsion from the festival, I presented myself to WikiLeaks as just another running dog of the mainstream media, a dunce, a stooge.

It was my own hopeless little journey. It started well. I went to Harrods, which is in front of Assange’s gilded cage, and bought a lobster sandwich. I stuffed my face with the sensational feast while mooching around the streets of Knightsbridge. A cherry-red SJ Ferrari was parked outside Prada. Giuseppe Zanotti held an anniversary exhibition of its shoes in the front window; each pair was given a name, and boring history — “Slim” was inspired by a beach in wintertime, “Venere” was a fusion of woman and serpent.

There were two Rolls-Royces on Sloane St, one white, one burgundy. Dolce & Gabbana, Bulgari, Versace. A serf in a top hat unlocked the gates to a private garden for a man with a greyhound.

The mutt galloped inside, and shat on the grass. “Spare a pound, please?” a beggar asked. She was from Brixton. “I’m a fucking mess.”

I got to the embassy. It was on a quiet street in a handsome red-brick building. All the curtains were drawn. You could probably see Hyde Park and the Thames from the top two levels. I thought that might at least afford the WikiLeaks savant some pleasure, but the policeman out front said Assange’s rooms were on the ground floor. Its only view was the Harrods loading bay.

He has been holed up there for two years. He works 17-hour days, has a bad cough and a personal trainer, watches TV (The West Wing, 60s sci-fi series The Twilight Zone), shreds anything that might leave a paper trail.

The officer outside the embassy was feeling chatty. He said three cops kept constant watch from the street. A fourth was on a rooftop. A fifth was inside the building, patrolling the stairwell and lobby — the rest of the building is apartments, and the east wing is the Colombian embassy. “All this for a sex offender,” he said. “And we’re not even here because of WikiLeaks and all that. It’s just the sex.”

Britain wants to extradite Assange to Sweden to face the sexual assault charges. The real agenda, according to WikiLeaks, is to ship him off to the US and sentence him to life imprisonment for espionage. Britain and Ecuador remain in talks to settle the impasse. Assange simply remains indoors. The furthest he has travelled in two years is to the little outdoor balcony.

On the second morning I attended Harris’s trial, he was busy inside his glass cage as the clock ticked towards 10am. He was talking to himself. It looked as though he was practising his lines. Was he perfecting the infinite ways he could mutter “I suppose so”?

On his opening day in the witness stand, he gave an astonishing performance — he mimed his amazing wobble board, he imitated the didgeridoo, he sang verses from “Jake the Peg”, his 1965 smash hit: “I’m Jake the Peg, diddle, diddle, diddle-dum, with an extra leg…”

There would be no repeat. After Harris’s strange rehearsal, he took his seat in the witness box, and Wass said to him, “You are a brilliant and polished entertainer, Mr Harris. There’s no question of that, and the Crown have no wish to challenge that.”

Harris nodded.

“But,” she said, with dreadful scorn, “this isn’t a talent show, is it, Mr Harris?”

The dry, papery voice said, “No.”

She took away his music. The judge took away his art. Jurors spotted Harris drawing in court; it’s against court regulations, and Harris felt the full weight of justice. “The sketches,” announced Justice Nigel Sweeney, “have been confiscated and destroyed.”

What did that leave him? He had his dignity and he had his defence — he didn’t molest or abuse anyone. Wass said his victims were groomed, bullied, traumatised. He denied it. “They’re all lying.” His right hand hung over the edge of the witness box. The fingers were splayed. The hand looked like a kind of starfish. Harris, diabetic, with a bad heart, an old man in a damp month, gasped for air.

Wass leafed through his autobiography and tried to place him at the scene of his alleged sex crimes. Malta, Cambridge, Portsmouth, London, Hawaii, Hamilton… Most showbiz memoirs are cheerful, self-satisfied histories of success and happiness. But Harris’s book is a depressing read.

He admits to a terrible relationship with his daughter. He describes poor old Alwen as arthritic, isolated, alopeciac — her hair started falling out in her 20s. “I’ve never been very good at discussing anything emotional.” The one time he told his mother he loved her was on her deathbed. He dwells on failures in his career, his limitations as an entertainer — his manager once insisted he sing a cover of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” on live TV, but it was a disaster. He couldn’t remember the words. He concludes he just wasn’t suited to that kind of song.

In his London Review of Books essay on the appalling Jimmy Savile, Andrew O’Hagan wrote, “There’s something creepy about British light entertainment and there always has been.” In his book, Harris writes about the backing dancers who appeared on his 1960s TV shows: “They were dressed in microskirts or hot pants. Whenever they danced you saw a flash of panties, which is why it quickly became known as the Twinkling Crotch Show.”

There are weird recollections. Bindi’s birth: “I gazed at this little naked girl child, marvelling at the minute size of everything. My eyes travelled down from her neck, to her delicate shoulders and the incredibly smooth skin of her stomach. I reached her genitals and skipped that part. My brain was saying, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. Why are you so uptight about nudity?’ I couldn’t help it.”

The time his mother knitted her own bathing suit, which had tassels: “I announced, ‘They look like pubic hairs.’ She swung her hand around and slapped me across the face. Mum didn’t talk to me for two days. I was 30 years old when that happened.”

Harris left out an even weirder memory. He shared it in an interview in 1974: “I grew up in the belief that sex was dirty. When I was 10 or 11, my mother decided I should see her naked to let me know it was all natural and everything. We had a bath together…”

The loveless book, the dismal affairs. He talked in court about sleeping with a penniless lodger. As for Bindi’s friend, Harris claimed they started having sex only after the girl turned 18, at her prompting: “She was flirtatious, coquettish.” It went on for 10 years. The court heard a brief history of blow-jobs. “Sex,” said Harris, “with no frills.”

Wass: “Ten years, and the only conversation you can recall is about cleaning your sperm from the sheets. It wasn’t a deep relationship, was it?”

His reply: “I don’t suppose it was.”

Harris and Assange, the two white-haired Australians, the light entertainer from Perth, the most dangerous man alive from Townsville, both brought low by sex scandals — but the comparison is odious. To reduce Assange to Harris’s level is to trivialise him, and distract from his work with WikiLeaks.

Assange and his supporters are wise to such tactics. Among them is the legendary Australian journalist John Pilger, who wrote a superb column in the New Statesman last year, noting the “lies, spite, jealousy, opportunism and pathetic animus” of Assange’s critics.

It was an honour to meet Pilger at the literary festival on The Strand. He was behind a desk, signing a stack of his books for the festival bookseller. A few days before I flew out, I’d managed to track down a copy of his first book, The Last Day: America’s Final Hours in Vietnam, published in 1976. I took it to London in case I was able to ask Pilger to sign it. The chance arrived.

He was astonished. “My god,” he said. “My first book. How did you get it? American edition! My god.”

He picked it up tenderly, turned the pages with delicate fingers. He shook his head. “My god.” Pilger, 74, was tanned and in good shape, tall and fit, with luxurious hair and an open, lovely smile. He was deeply moved to see a copy of his book, to hold it. I alerted him to the sticker inside the front cover, listing it as the property of the Nazareth Hospital in Philadelphia, and speculated that it may have passed into the hands of a hospitalised US soldier.

“That’s right,” he said. “A Vietnam vet.”

He signed it, and I said, “Thank you.”

“No,” he said, “thank you. Thank you so much.”

I should have asked Pilger if he’d heard Assange was pulled from the festival, but I didn’t want to risk ruining the moment. Festival director Jon Slack was standing nearby. I asked him about it, and he said, “It’s bollocks.” He described it as laughable. He laughed, not very sincerely.

Paula Morris, a New Zealand novelist who sat on the festival advisory board, also rubbished the claims. She said the board considered the idea of an interview with Assange, but no one was very keen on it. Slack went a bit further, and said Assange would have been “a distraction”.

All of which was kind of pathetic. Assange appeared via Skype at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, in March, and discussed the case of Edward Snowden, government surveillance, and “the military occupation” of civilian space, and hinted at WikiLeaks releasing fresh information — important subjects, addressed by a well-known international figure who happens to be Australian, which might have made him a speaker worth having at an otherwise rather obscure festival of Australia and New Zealand culture.

But the point of the rumour wasn’t about programming. It was about political interference. WikiLeaks spread the rumour on its Twitter account: “Assange talk blacklisted after pressure from NZ High Commission. Funding threat was twofold 1) if Assange spoke 2) if the threat was leaked.”

It emerged that the source was Australian journalist Andrew Fowler, author of an admiring book on Assange, The Most Dangerous Man in the World, and the person who had been keen to conduct the Skype interview. He put it about that the festival was ordered to pull Assange by the wife of Lockwood Smith, the New Zealand High Commissioner to London. Lockwood Smith’s wife! Fowler said it all happened at a cocktail party. A cocktail party?

I ran into Fowler at King’s College London. He said he wasn’t actually at the cocktail party, but that’s what he’d heard Lockwood Smith’s wife had said, and whether the “threat” was made directly or indirectly to the festival, it was hard to tell, but the fact of the matter was that Assange would not be appearing…

That weekend, I ridiculed the situation in my satirical diary column in the Sunday Star-Times. I invented a monologue for Assange, fulminating at the power and influence of Lockwood Smith’s wife at cocktail parties… I tried to balance the stupid column, make it clear I admired WikiLeaks, that Assange was heroic and brilliant.

It was all in vain. WikiLeaks on Twitter that day linked to the column with the dismissive comment, “Today’s idiotic op-ed trend: fake journal entries from Julian.” I wished I’d thought to ring the Ecuadorian embassy doorbell and present Assange with the lobster sandwich.

One of the few times Rolf Harris escaped from his gloom and torment at Southwark Crown Court was when he was shown a photograph of the house where he grew up. A plain weatherboard house, surrounded by jacarandas, fig trees, almond trees, box trees, draped with wisteria, on the banks of the Swan River — he climbed the trees and gorged on their fruit and nuts, he swam the Swan like a champ. At 16, he was the junior backstroke champion of Australia, competing in Melbourne in a borrowed pair of silk full-length bathers.

He was happy, too, when he sang to the jury: “Diddle, diddle, diddle-dum…” The papers reported it as bizarre, but it was calculated to disarm. It made the jury smile.

Don’t listen to him, said Wass, he’s a predator, using his fame to entrap and act out his vile fantasies. His defence lawyer said Wass didn’t really have much to go on, that she resorted to name-calling (“pervert”), and had proved nothing.

Wass brought her twitching little hand out again when she talked about the similarities in the versions told by Harris’s alleged victims. Harris, reaching inside the bikini pants worn by Bindi’s friend; Harris, with his hand up the skirt of a girl at a restaurant somewhere in New Zealand; Harris, grabbing a 15-year-old girl’s bottom at a hardware store in Hamilton. All hands, wandering, groping, fingering.

Harris: “They’re lying.”

Wass: “Why is it the same lie?”

Harris: “I don’t know. It didn’t happen. I’ve established that they’re lying.”

Wass: “No, you’re just saying they’re lying. You haven’t established that at all.” She stuck her paw out a bit further. “Do you accept there are similarities in what these women are telling us?”

Her hand, grubby and suggestive; his hand, that starfish, hanging on for dear life to the witness stand. In the front row, Alwen Harris, needing help whenever she sat down; two seats along from her, never right next to her, their daughter Bindi, a tough-looking broad in a leather jacket and a mauve top with butterflies on it. She’d told the court she wasn’t close to her father. “We hardly talk, Dad and I.”

When her friend told her that Harris had started abusing her when she was 13, Bindi phoned her father and challenged him. She banged her head against the wall while holding the receiver. She told him she wanted to stab herself with forks.

Wass: “She was beside herself?”

He supposed so, he supposed so, he supposed so. “I’ve never been very good at discussing anything emotional…” The line in his uptight book had come back to haunt him in the upstairs courtroom, case number T20130553, where onlookers with wet hats and warm slippers came to watch for a bit of light entertainment. The hope for a knighthood, the Queen sitting for her portrait — it was all as distant as Perth, as the Swan River, drifting past his house on the edge of a faraway continent.

?

?