Sep 4, 2019 Crime

Agitating for imprisonment as punishment for sexual violence is a mistake, write Tess Nichol.

How often do rapists stop to think about the lives they’ve left behind? This is a thought I’ve found myself returning to again and again in the last 18 months or so; ever since the Harvey Weinstein case split something open, encouraging countless women to divulge the very worst parts of their lives in the hope it might finally make a difference.

I thought about this most recently when I read about a case in New Zealand involving the sentencing of a teenager, the details of which Metro cannot repeat due to restrictions on reporting from Youth Court. The case was widely discussed on social media, with the general consensus being that justice had not been served – because the teen’s punishment was not severe enough. But what do we actually want – for a teenager to be sent to prison?

Nothing will undo the harm this young man’s offending has caused, including sending him to prison. To demand that happen anyway despite his being at low risk of offending again is a capitulation to the empty satisfaction of punishment. And punishment is not justice. It is also counterproductive to the wider feminist cause. As American writer Alex Press put it in a piece for Vox about #MeToo last year: “Directing the movement’s energy into the criminal justice system doesn’t build the power we need to stop sexual violence: It allies us with a system that’s incompatible with liberation.”

Part of #MeToo is about figuring out what comes next, after the accusations. And the fact is I don’t think the next logical step to believing women is to throw every rapist in jail. Rape isn’t like other crimes, in that many men, particularly young ones, genuinely don’t think they are rapists and neither do their peers. That you can commit such an obvious violation against someone and not recognise it as such is an almost unique feature of sexual assault, which makes sense if you consider the deeply sick gender dynamics between men and women, where the former so routinely dismisses the humanity of the latter.

Believing we can fix this by relying on the state to mete out carceral punishment is a huge mistake. Feminism is, at its best, not just about improving the lot of women but about dismantling patriarchal structures which oppress not only women, but all vulnerable communities, which can include men. The prison system is quite possibly the structure with the most amount of potential to oppress vulnerable people, through, for example, unequal application of the law. To advocate for expanding its powers would be an overcorrection from feminists understandably, but I believe wrongly, keen to finally see violent men grapple with the consequences of their actions.

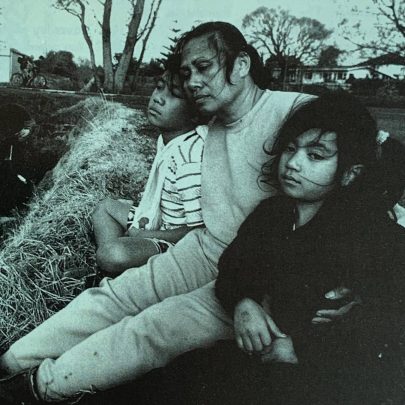

Consider that the kinds of men others already have a harder time believing are rapists – wealthy men, especially wealthy white men, socially respected men – are the ones similarly favoured when it comes to handing out prison sentences. The flipside to this is obvious but I’ll spell it out: if we as feminists agitate to put more men in prison for crimes of sexual violence then brown men, poor men, men who are already more likely to be criminalised, will go to prison more frequently, despite sexual violence being a problem experienced in every facet of society.

When it comes to victims of sexual violence, Elisabeth McDonald (co-author of the book From “Real Rape” to Real Justice: Prosecuting Rape in New Zealand), is described by journalist Donna Chisholm in a 2014 North & South article as explaining how “many complainants, particularly in acquaintance rapes, simply want acknowledgment, apology and for the offender to get help to change his behaviour”.

I believe that what women as a class want is to live free from the fear that the men whose paths they cross will commit acts of sexual violence against them. With exceptions for rare high risk offending, this is not achieved by tending toward favouring carceral punishment.

Accountability and responsibility aren’t outcomes we can only achieve through a prison sentence, and arguably the threshold for a prison sentence to be given out in cases of sexual violence is so high, that if this is our only recourse to “justice” then women will routinely fail to see any. The knowledge the threshold is so high means many won’t bother to report assault in the first place. We urgently need to think of different and better ways to deal with sexual violence both before and after the fact.

An earlier version of this story included details of a case held in the Youth Court, which Metro does not have permission to publish. This story has been amended to remove details of the case, and Metro apologises for the error.