Dec 8, 2015 Crime

He was locked up in a mental asylum after killing his father. She is a writer with a PhD in literature and philosophy. Now, they want their unlikely love story to expose what they see as critical failings in our forensic mental health services. Donna Chisholm reports.

This article was first published in the October 2015 issue of North & South magazine.

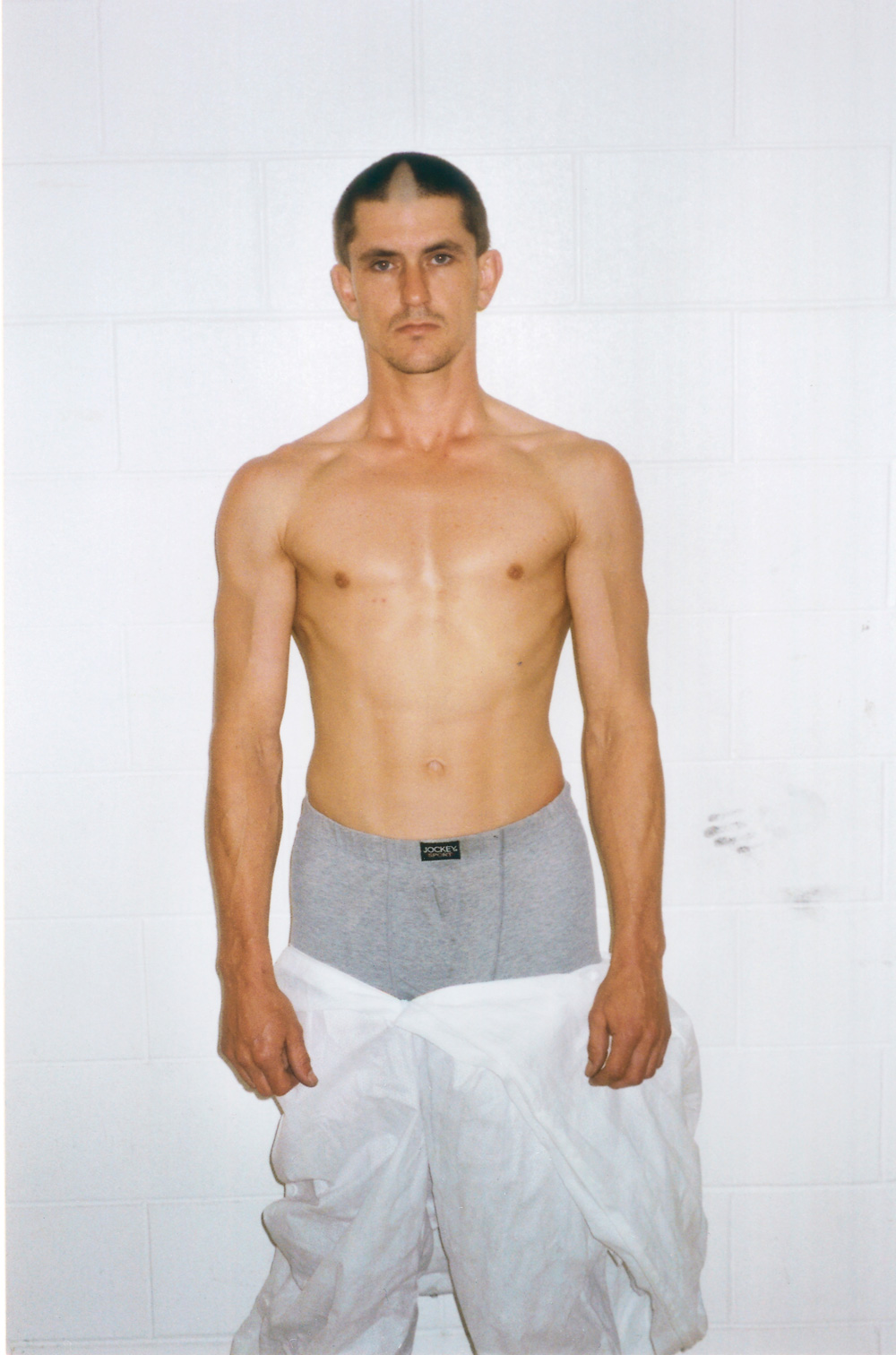

On a Thursday morning in September 2010, Paul Ellis balanced his laptop on the windowsill of his tiny room at Auckland’s Mason Clinic, the country’s biggest forensic psychiatric hospital, and tapped out a message for help.

The laptop was banned in there, and there was no internet. But Ellis, an enterprising engineer, had discovered that the position on the ledge enabled him to connect to Wi-Fi from the neighbouring Unitec and, for the first time in three months, communicate with someone outside the hospital walls.

Ellis, found not guilty by reason of insanity of the 2001 bludgeoning death of his father, Tony, had been given leave from hospital care in 2008, but was locked up again two years later, when staff found out he hadn’t been taking the drugs prescribed for his “schizophrenia”.

Ellis’s message was simple – “I don’t have schizophrenia, I don’t need schizophrenia drugs – please help get me out of here.”

I was one of the people who received that email plea, after meeting and writing about Ellis the year before. Like the others, I didn’t see how I could help. Suggesting publicly, on the word of a temporarily insane man, that the doctors had it wrong was never going to fly, particularly after such a gruesome killing. An understandably wary public had no appetite for such a story – why couldn’t he just take the meds and get on with it?

But today, there is mounting evidence that, in this instance, the patient did know best. Today, Paul Ellis hasn’t taken any medication for seven years and remains well. He has set up his own engineering business and is completing a $400,000 extension on his home. He has a supportive partner who has a PhD in literature and philosophy, and, finally, a new diagnosis that supports his long-held belief that he never had schizophrenia at all.

Now his partner, writer Aimee Inomata, has written The Special Patient, a book about his case. They hope it exposes what they see as failings in forensic psychiatry, gives patients hope of recovery and makes clinicians think again before branding the mentally ill as incurable.

If there is any obvious indication of Paul Ellis’s enduring mental wellbeing, it’s that today, nearly 10 months into a home renovation that has seen him and Inomata living out of boxes in a few small rooms, he remains relaxed and sanguine in the chaos around them.

For any couple, this would have been an enormous and stressful project, lifting their 1920s Californian bungalow in Mt Albert, Auckland, to provide garage and workspace below, and vastly extending the living area above. Funded partly by the sale of the Maraetai home he bought more than 20 years ago, it’ll take two more years to complete.

But for someone who came out of the Mason Clinic five years ago with no job, a mortgage in arrears and a former relationship in tatters, this new life is an extraordinary achievement.

When he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia after killing his father in October 2001, and locked up under compulsory treatment as a special patient – who could be released only on the orders of the Minister of Health – Ellis wasn’t in any position to question the doctors.

“There was a whole lot of confusion; stuff going on for me that was overwhelming so I couldn’t sit back and think, ‘Yes, this is right’ or ‘This isn’t right’, but at the time it was a bit of an answer – okay, this is why I did it, because I suffer from this illness; this is the reason it happened. At the time, I needed that. When you do something like I did, you have trouble thinking how you could ever trust yourself again. I’d done something that I knew I wouldn’t really do.”

When I interviewed Ellis for the 2009 Metro magazine story, “The Night I Killed My Father”, he told me that though he was drug- and alcohol-free, he was taking enough anti-psychotics to “sedate a horse”. He admits now that he was lying – it was a line to keep his doctors happy. In fact, he had begun tapering off his medication while still in the Mason Clinic in 2005, using a technique common to patients known as “tonguing”, and by late 2008, was taking no drugs at all.

READ MORE: Donna Chisholm’s 2009 story: “The Night I Killed My Father”.

In 2005, he was working days at a South Auckland engineering firm, and returning to the Mason Clinic at nights, but the 200mg morning dose of the anti-psychotic quetiapine saw him regularly falling asleep at the train station and made him muddle-headed when operating hazardous equipment at work. It convinced him to try to reduce the dose. “You all line up in the morning and the evening to have your medication. You take it, drink the water, put the pill under your tongue, then spit it out later.”

He started to feel better – more alive, alert and “in touch with myself”.

In 2006, he began working with a new company full time as a senior engineer. It was a challenging and stressful role, but he coped well, while continuing to restrict his doses. “I found it helped me concentrate and perform better and there was no difference in my thinking patterns, no paranoia, or other signs of illness.”

Months after he was granted ministerial long leave from hospital in April 2008, he took his last dose of quetiapine.

It now seems likely Ellis never had schizophrenia at all, but a drug-induced psychosis related to his previous heavy cannabis use. It’s the diagnosis preferred by an internationally published independent academic psychiatrist who reviewed the Ellis case over four months in 2011-2012 and has given expert witness evidence in court cases around the world. The management of his risk, the psychiatrist said, depended mainly on ensuring he stayed off drugs and alcohol, which he has so far done without problem.

“If someone gets cancer, and they kick it, they’re a hero. I don’t really see a mental illness being any different.”

Ellis’s recovery without medication is the part of the story he hopes will resonate most with people with mental illness and go some way to changing society’s perception of them. “If someone gets cancer, and they kick it,” says Ellis, “they’re a hero. I don’t really see a mental illness being any different. With a mental illness, for some reason we’re told you’ve got it for the rest of your life, like a diabetic with insulin, and to me that’s bullshit. I can only imagine we are being sold that crap by psychiatrists and pharmaceutical companies. Why would you say that to a person who is already in a vulnerable position in their life? They’re as low as they can go and then you tell them they’re never going to get better – why would you do that?”

Ellis, now 48, was only just out of the Mason Clinic after his readmission in 2010 when he met Aimee Inomata, who lived with her parents in the same Mt Albert street as him and his then-partner. By then, his two-year relationship was in terminal decline. She had told the clinic Ellis wasn’t taking his medication, probably imagining, he says, that he’d be locked up for a weekend rather than five months. The pair parted in 2011.

Soon after he’d returned home from the clinic, Ellis told Inomata where he’d been for those five months, and why. Before then, he’d said only, “If you knew what I’d done, you’d cross the street rather than talk to me.”

She went home and Googled him, “as you do”. “I was trying to get my head around it and think, ‘Well, who is this guy, what kind of man is he?’” She wasn’t so much checking his psychiatric background – headlines such as “Crazed killer’s legacy” told her much of what she already knew – as ensuring he’d told her the truth.

Her mother had befriended Ellis first, she says, stopping to chat when she saw him painting the house or mowing the lawns when she was walking the dog.

Inomata, knowing Ellis was in a relationship, regarded him as strictly off-limits. Her biggest impression from the odd glimpse she’d caught of him was that he was “a reserved and serious man”, perhaps with a touch of A.A. Milne’s Eeyore about him. That, and the fact he was a good-looking man. “But then, I’d encountered a lot of guys like that. Nice to look at, but when they opened their mouths it was all over.”

But this time, when Ellis did open his mouth and they had their first conversation, it was all just about to begin. They connected over German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. When Ellis told her philosophy, particularly Nietzsche’s, was a keen interest of his, he asked if she’d heard of him. Yes, she replied, a chapter in her University of Sydney PhD had been devoted to him.

“The night I knew he was absolutely the right person for me, and I couldn’t resist this any longer, was when we went to dinner in Mission Bay, and he started reciting Nietzsche verbatim. I thought, ‘Oh my God, I surrender!’ It really was like that. Up to that point, I’d thought he was cute – but did he have a brain?”

At 43 and single, Inomata had no intention of settling with any man. “I was quite happy. I thought I was going to be a crazy old maid with dogs. I have friends whose biggest fear was being old and alone. For me, what’s far more frightening is the idea of being with someone I didn’t really want to be with just because I was afraid of being on my own. That to me would be hell.”

She says her natural caution was more the result of her own attitudes to relationships than anything Ellis had done. “I was afraid of getting involved with him and then deciding I didn’t want to be, and I knew that would be devastating for him and not much fun for me, either.”

Her mother, she says, while initially worried about the wisdom of the relationship, is now supportive. At a review panel, before Ellis was discharged from special patient status last year, she even read a statement to the judge. “She said my daughter is one of the most precious things in my life – there’s no way I would allow her to be in any danger.”

Inomata says she feels safer with Ellis “than any other man, ever. And I trusted that instinct. The picture that’s been created of Paul, he sounds like a really crazy person, but it was always clear to me from his behaviour, from who he was, from day-to-day encounters even before we got together, that he didn’t have schizophrenia.”

Ellis accepts his background is a big thing for a woman to take on.

“We’ve all got a past, yeah? For most people I’ve met, in some way it’s going to affect the present. Most people wouldn’t want it and if I had a choice I would trade it in for something else. But it’s what I have and Aimee doesn’t see me – and I don’t see myself – as that person I was in the past.”

Ironically, the ministerial letter that would have removed Ellis from special patient status had been on Associate Minister Peter Dunne’s desk ready to be signed off in 2010 when his ex blew the whistle on his noncompliance.

The diagnosis of mental illness is an inexact science – in the vast majority of cases, there are no blood tests or brain scans that will give a definitive answer. In the famous Rosenhan experiment published in 1973, Stanford University psychologist David Rosenhan proved just how easy a diagnosis is to make and how difficult to refute.

He had eight healthy associates feign auditory hallucinations to try to gain admission to 12 different psychiatric hospitals in the US. Among the five men and three women were three psychologists, a paediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter and a housewife. All were admitted, for a period of seven to 52 days, and all but one were diagnosed with schizophrenia and discharged with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in remission. The “pseudo-patients” had all behaved completely normally after admission – “each was told he (or she) would have to get out by his own devices, essentially by convincing the staff that he was sane”.

Despite their “show” of sanity, says Rosenhan, the pseudo-patients were never detected. “Rather, the evidence is strong that, once labelled schizophrenic, the pseudo-patient was stuck with that label. If the pseudo-patient was to be discharged, he must naturally be ‘in remission’, but he was not sane, nor, in the institution’s view, had he ever been sane.’”

Ironically, it was quite common for other patients to “detect” their sanity, with 35 of 118 patients on the admissions ward voicing their suspicions.

In a second Rosenhan experiment, staff at a psychiatric hospital were told that one or more pseudo-patients would try to gain admission in the next three months. Of 193 patients admitted for treatment, 41 were alleged “with high confidence” to be pseudo-patients by at least one member of staff and 23 were considered suspect by at least one psychiatrist. But Rosenhan had not tried to get any pseudo-patients admitted during that period.

“The experiment is instructive. It indicates that the tendency to designate sane people as insane can be reversed when the stakes (in this case, prestige and diagnostic acumen) are high.”

This, of course, is not to say Paul Ellis was always sane – he clearly was not at the time he killed his father – but that sanity at any time can be hard to prove.

In 2010, when he was no longer suffering any symptoms, let alone psychosis, it took a five-month battle of wills with his treating doctors before they agreed to allow him to stay medication-free. “They wouldn’t let me outside, they wouldn’t give me leave. They tried to make things as difficult as possible. I think they tried to promote me to become unwell. I tried to seek help but everyone fobbed me off. I realise now that there’s nothing you can do, really. If you’re locked up in an insane asylum and trying to tell people on the outside that there’s nothing wrong with you, people just automatically assume you’re crazy.”

But in November, an independent review panel conceded Ellis had a strong argument not to resume the anti-psychotics, and his long leave – to return to the community without medication – was reinstated. By that time, there had been five different diagnoses of Ellis’s illness. Before the killing, when he was temporarily admitted to the Counties Manukau residential mental health crisis unit Tiaho Mai, it was drug-induced psychosis. After his father’s death, it became, variously, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and personality disorder as psychiatrists said he showed features of all of these.

The psychiatrist Ellis’s lawyer hired in 2011, however, argued cogently against the last four labels, although, of the personality disorder, he said, “I have no particular issue with the evidence and arguments in favour of the diagnosis of complex personality disorder.

“On the other hand, I would tend to see the described features of stubbornness, emotional superficiality and self-centredness as traits rather than necessarily indicating a disorder per se. It would appear these features have not impaired his occupational performance but have coloured his relationships to some extent.” He said that in a four-hour interview, Ellis displayed no clear-cut signs or symptoms of mental disorder. Ellis had had two previous psychotic episodes – both after suddenly stopping heavy cannabis use – once in 1994, and the other in 2001 when he killed his father. The 1994 episode gradually resolved spontaneously.

While Ellis and Inomata believe some schizophrenia diagnoses are more about protecting the back of the health professionals – because it enables them to keep patients on medication for life – the psychiatrist, who declined to be named, says a precautionary approach to diagnosis and treatment is usually justifiable, especially in cases with a history of very serious offending. “I think this accounts for most cases of perceived or alleged ‘back protection’ and may be motivated by the clinical obligation to protect the public interest; on the other hand, I believe excessively defensive practice is also problematic.”

He argued that cannabis-withdrawal psychosis, while apparently much less common than that associated with chronic cannabis intoxication, is likely to be under-recognised and under-diagnosed. “It certainly deserves more study.” The causes are still poorly understood, he says, but may include tolerance to large doses of cannabis, family history and, in Ellis’s case, the occasional use of other drugs – notably amphetamine, the abuse of which is well known to produce a schizophrenia-like psychosis.

In his report, the psychiatrist said while it might seem paradoxical that Ellis’s psychosis became distinctly worse when he stopped smoking cannabis, it was understandable as a “sudden loss of antipsychotic activity and mood stabilisation by cannabidiol, one of the constituents of cannabis”.

He told North & South Ellis’s assertion that severe mental illness isn’t necessarily a lifelong condition was correct only for a subset of patients with a clear cause like his. “More often there is no such definable cause and the chronic relapsing illness model is sadly apposite but also realistic.”

While knowledge about medications for mental disorders is growing, he says, it is “dwarfed by the vast amount we don’t know”.

There is increasing debate, for example, about the value of psychotropic medications, and whether schizophrenia itself is indeed a life-long disabling condition, or would spontaneously resolve without treatment. In a British Medical Journal debate in May, Peter Gøtzsche, professor and director of the Nordic Cochrane Centre in Denmark, said psychiatric drugs did more harm than good, and trials into their efficacy had almost all been biased. “Given their lack of benefit, I estimate we could stop almost all psychotropic drugs without causing harm, by dropping all anti-depressants, ADHD drugs and dementia drugs… and using only a fraction of the antipsychotics and benzodiazepines we currently use.”

That view was countered by others who argued the drugs did work, had substantially reduced suicide risk and were badly needed, because psychiatric conditions are the fifth leading cause of disability worldwide.

Mason Clinic clinical director Dr Jeremy Skipworth told North & South that Ellis’s initial diagnosis of schizophrenia had been continuously revised since 2001 and “has not been the preferred diagnosis for many years. This reflects Mr Ellis’ clinical presentation and recovery, and takes into account his period off treatment. Such changes in diagnostic formulation are common in psychiatry, as they are in other areas of medicine. We also need to be open to the possibility that new information in the future may challenge our current formulation.”

He said Ellis’ decision to reduce and then stop his medication, without involving his doctors, was a “serious breach of trust” in that relationship, and a serious breach of his ministerial leave conditions that understandably led to his leave being revoked. “A supervised reduction in medication would have been a much better and safer process.”

But Ellis and Inomata say he didn’t ask to reduce his morning medication “because it was drummed into him that he had to keep the medication in his body at a particular level”.

When he did ask to reduce his dosages, the doctors weren’t happy to allow it because they feared the stresses in his life – including divorce from his wife – would spark another psychotic episode. “He was on a ridiculous amount of medication,” says Inomata.

Now there is none, and nor is there a joint of cannabis or a glass of beer. “I haven’t touched alcohol or cannabis since it happened and I can’t ever see myself touching it again,” Ellis says.

He can see now that his prior use – three or four joints a day and being “stoned” every day for about 10 years – stunted his emotional development and allowed him to escape from the pressures of life he should have dealt with. “The feeling that you don’t need to run away from things now is pretty empowering.”

Ellis says his experience hasn’t changed his view that for most people, cannabis taken in moderation is not harmful. “For me it was a dangerous drug. If you abuse it like I did – and I’m excessive – it’s a dangerous drug like alcohol.”

Inomata’s book is under consideration by several publishing houses. She says a number of supportive nurses suggested Ellis write it himself. She decided to do so only after becoming incensed at the way he was treated at successive special patient reviews, and seeing error after error introduced into psychiatric assessments to fit with their diagnoses.

“On the surface, it’s all very polite, but the sub-text is, it’s an adult-child relationship, an asylum mentality: you’ve been a bad boy and you have to prove to us you can be a good boy. I found it quite disturbing because I thought, how can anyone come out of this? I know how strong Paul is, and I thought, if you’re not Paul, how do you come out of this not beaten? Not feeling like you’re a defective human being who is never going to be well? I thought, this is not about mental health, and that’s what made me so angry.”

She says the current system “takes people who are already clearly broken and then breaks them right down and expects them somehow to be able to put themselves together and function. But it’s about functioning just enough so that you can exist. Living and enjoying your life and exercising autonomy are not encouraged.”

For Ellis and Inomata, amid the cardboard boxes, the scaffolding, and the sawdust, two good lives are, finally, being fully lived. As their sage Nietzsche wrote: “The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe. If you try it, you will be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.”

READ MORE: Donna Chisholm’s 2009 story: “The Night I Killed My Father”.