Jan 31, 2018 Crime

High time

A spate of deaths linked to synthetic cannabis is just the latest evidence New Zealand’s prohibition-and-punishment approach to drug use is failing.

Paddy Gower was in charge of moderation, possibly the first of many oxymorons that night, and Bill English and Jacinda Ardern faced off across their podiums, ready to demonstrate their intelligence, their foresight and their overall fitness for running the country.

The crowd was amped, involved, hanging on every word as the topics ranged from housing and child poverty to immigration and infrastructure. One hour and six minutes in, Gower steered the conversation towards drug law reform and the decriminalisation of cannabis.

Gower: “Let’s say there’s a proposed bill put up that means no charges if you’re caught with 40 grams of cannabis or less. That’s about the size of a muesli bar.”

A muesli bar? The crowd roared with laughter. Bill English heartily joined in. “You expect people to eat it?” Jacinda asked, grinning nervously.

The laughter died on the hot air of the room. “Would you vote for that, Bill English?” Gower asked. English’s expression turned to one of gravitas.

“No, I wouldn’t at the moment. There’s a few countries who are trying decriminalisation. I guess someone has to make the case there would be less harm from decriminalisation. Effectively, the police exercise discretion now so you’ve got pragmatic, low decriminalisation in New Zealand anyway. But look, this is a drug, which after years of debate in New Zealand still remains an illegal drug, and the reason for that is because you see the damage it does to people. Now if these other countries, like Portugal, or Colorado in the United States, can show that a more liberal regime would mean less harm, then I’d look at it.”

Ardern was quick to point out Labour weren’t campaigning on it, just in case anyone thought her party might be pro-drugs. “But the Law Commission has done an incredible piece of work that says they’d like to see us take much more of a health-based approach instead of a criminal justice approach.”

“So no to decriminalisation?” Gower pushed.

“I do want to see some change. I want to see us dealing with this as a health issue and not a justice issue. Locking someone up for smoking weed is a waste of money and doesn’t help fix an individual’s problem. Putting them into rehab does.”

Gower: “But if you say that, then why won’t you vote for decriminalisation? Why won’t you give us a straight answer?”

Ardern gripped the podium and prattled: “Because we could do that now but we’re not. We haven’t invested enough in rehabilitation and support for drug and alcohol addiction services.”

And that was that for drug law reform in the debate. The health and human rights aspirations of the nation’s drug users, the examination of a system proven to be inherently racist, and the clear moral and human wrong of imprisoning people for drug use with all of its consequences, distilled into those two minutes: incomprehensible liberal babbling and a right-wing study in dissembling and disingenuity; a how-to guide on being cynically obtuse.

It was the moment people all around the country who are professionally and personally concerned about the harms being caused by our current drug laws collectively face-palmed.

An 11-year-old watching the debate next to me shook his head. “These are our leaders? They’re cringe, bro.”

Crunching the numbers

For the record, let’s state an unassailable fact: New Zealand’s system of prohibition under our current drug laws causes more harm than it prevents. A spoonful of sugar from Jacinda or Bill will not help that medicine go down.

In 2016, police charged 6310 people with drug offences, with 27 per cent, or 1700, of those for the relatively minor charges of possession or use. That same year, the courts convicted 5011 people, again with 27 per cent, or 1352, of those for possession or use. People under 30 made up nearly half of the convictions; 81 per cent were male. Despite Maori making up only 15 per cent of the population, 42 per cent of those convicted were tangata whenua. Of the drug conviction total, 3296 were for marijuana offences, and 1186, or 36 per cent, of those were for simple possession or use.

Does the punishment fit the crime? Maybe if you believe in some kind of dystopian fundamentalist-Christian hell, but not in progressive New Zealand. The opportunity costs for people convicted of drug possession multiply like herpes, the gift that keeps on giving. A conviction can severely affect access to credit, insurance, accommodation, education and travel, and damage or destroy personal relationships and family. If a conviction results in a custodial sentence, the offender will enter a university of crime, where they will likely be forced to join a gang just to protect themselves.

When you consider around 410,000 New Zealanders admit to regularly using cannabis, and 80 per cent of young people admit to trying it, two conclusions are obvious: the police are either very bad at their job or are offering an unprecedented amount of discretion; and why in 2017 are we still arresting and convicting people for possession of drugs anyway? When enforcing our law strips people of their fundamental right to opportunity — especially for those under 25 whose lives are still beginning — we have lifted the use of drugs beyond being a health issue and into the domain of human rights.

Compounding the egregious wrong of our laws is the cost of enforcing them, and the cost of our failure to put that money to better use for education and rehabilitation. The Ministry of Health’s Drug Harm Index puts the cost of New Zealand’s little territory of the drug war at $273 million for law enforcement, with another $78 million in ministry interventions.

Yet the Treasury estimates that if marijuana were legalised, the tax take alone would be around $245 million annually. That’s nearly as much as we currently spend trying to fight an already entrenched black market being run by our worst kind of entrepreneurs: the gangs.

Statistics released by the National Drug Intelligence Bureau to Metro under the Official Information Act show for all that investment, really all we’re doing is finding more drugs. Because, guess what? New Zealanders love drugs. Methamphetamine seizures have climbed from just 13kg in 2012 to an almost unbelievable 941kg in 2016. Remember John Key and the so-called “success” of the Meth Plan? Seizing nearly 1000kg in under a year is proof of increased demand, not less. In 2012, 498kg of precursors were seized; in 2016, that had climbed to 1243kg. Cocaine seizures more than doubled from 15kg in 2012 to 36kg in 2016. Heroin and opioid drugs remained largely static, moving from a mere 18 grams in 2012 to 53 grams in 2016 (with the exception of one large bust of 16kg in 2014). LSD seizures increased from just over 1000 tabs in 2012 to more than 23,000 in 2016. The only drugs to fall in the statistics are two of the safest drugs in the world: ecstasy, which fell from 218,000 tablets in 2012 to 118,000 in 2016, and marijuana, which fell from nearly 150,000 plants in 2012 to 122,000 in 2016.

It’s hard not to wonder if the fall in marijuana seizures and the rise in synthetics, which have been linked to 20 deaths this year, are related. If marijuana were legal and available, would those people still be alive today?

If you’re still not convinced that prohibition isn’t lowering demand, the National Drug Policy 2015 to 2020 estimates that 44 per cent of adult New Zealanders have tried an illegal drug at some point in their lives. That’s more than two million people who are by definition criminals. Look around next time you’re walking down Queen St or sitting at the mall in St Lukes. Statistically, nearly half the adults around you have tried drugs.

Back in October 2009, Metro asked if New Zealand’s drug laws were due for a rethink. Eight years on, the era of polite suggestions has clearly passed. Prohibition by any metric is a bucket of fail. It’s time to demand change.

Is there racism in our drug laws?

Drug Foundation CEO Ross Bell is fired up. He’s furious about the ongoing hypocrisy of Parliament. Many of its members have admitted, either freely or under media coercion, to having smoked pot. Yet there they are, occupying their seats by the good fortune of having avoided arrest, and now lecturing the rest of New Zealand on the perils of drugs they enjoyed without consequence.

“Politicians wouldn’t want to be in the same boat they put others in,” says Bell. “Many MPs admit to smoking weed and breaking the law. If any of them had a criminal conviction, there’s no way they’d be in Parliament. So where do they get off thinking it’s okay for other people to get a criminal conviction?”

It’s a good question. The conviction of those 1186 people last year for marijuana possession or use gives the lie to English’s claim police discretion has created a kind of de facto decriminalisation. Besides, is that really how we want to run and enforce our drug laws, through the prism of a police officer’s value judgements? The fundamental concept underpinning democracy is that everyone is equal under the law. Given that Maori are 15 per cent of the population but account for 42 per cent of the convictions, they are without question receiving what AUT law lecturer Khylee Quince calls “the pointy end of discretion”. Are our drug laws facilitating systemic racism?

“It is, as is the criminal justice system as a whole,” says Quince. “But the little part that concerns drug offending? It’s particularly racist.” From behind her desk on the top floor of AUT’s law faculty, an incongruous collection of posters on the walls including Jon Snow, Lemmy from Motorhead, Star Wars and Liverpool Football Club, she is animated. “There are only two ways you can explain that data. One is differential involvement, which is that there are more Maori engaged in that sort of offending. The other is the discrimination thesis, which is that you are more likely to be looked at, caught, processed, charged, convicted.”

She cites research papers which show little difference between Maori use of cannabis with other population cohorts in New Zealand. “We know it’s not differential involvement, not [with] cannabis at least, so it’s absolutely the second thesis, which is you’re discriminated against in the way that you’re processed.”

In 2015 on TV3’s The Nation, Police Commissioner Mike Bush admitted that the police held an “unconscious bias” towards Maori, and that was particularly reflected in the way they were likely to apply discretion.

Bell: “Let’s call it what it is, which is institutional racism. The data backs up that view, and I certainly hold it; when you look at the rates of everything from police apprehensions to arrests to getting before the court to ultimately getting a conviction including a custodial sentence, Maori in each of those stages are much more likely to have them happen. There’s no reason other than racism to explain that away.”

Says Quince: “Judges can only deal with people who make it to that part of the system and there are a whole lot of processes before you get there. Something like 80 per cent of offenders are dealt with in an informal way. The criminal justice system largely operates as a process of attrition. It couldn’t possibly cope with every offender of every offence being formally processed. Which is why we place most responsibility for discretion with the first responders, and that’s the police. [These statistics] are to be laid almost entirely at the feet of the police.”

Quince tells a story from her partner, a Year 8 teacher in South Auckland. “He conducts a weekly quiz with the children, and the question that week was, ‘What do you call the people in a courtroom whose job it is to decide if you are innocent or guilty?’ A Maori kid at the front waves his hand: ‘Oh, oh, oh!’ Yes? ‘Pakehas.’” We both laugh, then exchange a guilty look. Quince shakes her head. “Sad but true.”

The police view of drugs in New Zealand

Today the police line to Metro is that our drug laws are neither hypocritical nor racist, and if New Zealand is going to beat its drug problem, we need to double down on our current strategies. Richard Chambers, assistant commissioner (investigations), is friendly, earnest and clearly passionate about the harm drugs like methamphetamine are causing our communities. But is New Zealand winning the drug war? “The results we get we’re very proud of. We get some outstanding results in terms of holding accountable those who supply and distribute drugs. People go to jail for a very long time. We can attack their asset bases. The reality is internationally, the illicit drug trade is complex and is going to be challenging and it’s changing all the time.”

Good results like the huge disparity in the Maori rates of conviction and incarceration? Chambers doesn’t believe that there’s anything racist in the statistics. “I would disagree with that view. What I would say is that Maori are over-represented in a number of statistics, and that’s something we’re working hard to change. One of our goals by 2025 is to reduce Maori offending rates by 25 per cent. It’s the right thing to do for Maori people. I vehemently disagree with the comment about it being racist.”

But on the commissioner’s comments about unconscious bias, I get an answer that might be straight out of Yes, Minister: “As the commissioner said, unconscious bias is something we need to be conscious of in making our decisions, and that’s healthy. That’s got to be a healthy thing to have at the front of our minds. Whenever we engage with any person, irrespective of their background, age, gender, ethnicity, or their lives to that point. So it’s healthy to have in our minds unconscious bias, as the commissioner said, to ensure we’re all impartial. It’s what we sign up to. Actually, I think our country’s come a very long way.”

Confused? So is the police view on what our laws should be. On the one hand Chambers is emphatic that “the law is the law, and the police are here to enforce the law”. They hold no view on what the law should be. But when pushed on whether, if police developed a view, they would contribute to a select committee process, for example, he says yes, but options like decriminalisation or legalisation with intelligent regulation would be firmly off the table. Asked if he could ever countenance the legalisation of P, he’s adamant. “Absolutely not. We’d hate to think that such a discussion would even be entertained. Because of the harm it’s caused to families, to individuals, the violence, it’s an incredibly addictive drug that has the potential to destroy the heart and soul of our country. No one is going to say that’s okay.”

Chambers expresses compassion for people caught using or possessing drugs, and freely admits that the criminal justice system isn’t always the best place for them. Like former PM Bill English, he cites police discretion as being part of a more modern approach. “A conviction can often cause a long-term impact on someone’s opportunity, be it employment or travel. But the law is the law. More often than not people take responsibility for their actions, and putting them through the criminal justice system doesn’t necessarily help them.

“We would rather see less harm caused, that they understand the rules and they respect them. And for that reason, that’s why we exercise discretion. We take a common-sense approach in the way we enforce the law, but if someone’s been caught before and been formally warned before, then you have to ask the question: well, really? Perhaps sending them to court is the right thing to do. How many times do you have to take a stand before they realise? Sometimes people don’t help themselves and then it’s them that makes the decision.”

There are two significant problems in the police view on drugs: firstly they view them as evil and pernicious and the desire to punish people — as with many New Zealanders — runs deep. Secondly, and where it’s easier to have genuine sympathy for the police, is that they are on the frontline of dealing with the crime and violence caused by methamphetamine and the people who control the industry. The bashings, the kidnappings, the brutal murders, the unravelling of people’s lives. But isn’t that one of the most cogent and powerful arguments for reform? Surely it’s a kind of madness to leave such a harmful billion-dollar industry in the hands of people like the Head Hunters or the Mongrel Mob, who, as Chambers says, are motivated only by rapacious greed.

Where I find common ground with Chambers is in his clearly genuine desire to alleviate the harm police see every day in our communities. But just like our politicians, police resist understanding it is prohibition that creates the preconditions for these harms to occur.

“It’s a shame that gangs choose to meddle in the supply and distribution of drugs for profit,” Chambers says. “They trade off other people’s misery and addiction to further their own interests. Certainly I have no sympathy for those who go to jail… We’ll not only hold them accountable where we can for their involvement with drugs, but we’ll also take their assets in the process, and we’ll be doing more of it in the next few years.”

It’s classic police-speak. The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Where the drug money goes

The doyen of free-market capitalism, Milton Friedman, said: “If you look at the drug war from a purely economic point of view, the role of Government is to protect the drug cartels. That is literally true.”

Methamphetamine and other drugs are the financial oxygen that has allowed gangs like the Head Hunters to prosper and grow, and they’ve done it all in the garden of prohibition. Prohibition creates the risks that underpin their enormous profit margins and ensures failure to comply with their often arbitrary black-market rules will be met with violence. Police have often observed that if some of our top gang members applied themselves to legitimate business, they would probably do well. But there are few legitimate businesses that come with high-level dealing’s access to cash, sex and street power. An hour after my interview with Chambers, he sends me a New Zealand Herald article on the seizure of senior Head Hunter Wayne Doyle’s alleged $6 million-plus asset base, miraculously acquired as a state beneficiary. Police were serving the warrants as we spoke.

Police now regularly seize cash and property such as houses, cars and boats under our Proceeds of Crime legislation. They are jubilant about the power of this new weapon. But instead of the money being used for treatment, rehabilitation, or education, most of it ends up in the Government’s Consolidated Fund.

Prohibition entrenches the gangs and their profits, ensuring all the harm they cause continues to propagate. Surely, the fastest way to deprive them of their lifeblood is to change the game?

“This is where society fails to understand what prohibition is,” says Bell. “Prohibition is a policy choice. The Government has a range of policy choices available to them, and each of those choices brings different outcomes. So when you’ve made the policy choice as a Government to not take any control over drugs, you then hand all of that control to the black market. That’s what governments do when they say, we’re going to stick with the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. That’s a policy choice, to leave control to the black market and the people in it. It’s insanity. It’s some of the most insane policy making.

“How do gangs control their market share? Through violence. So when the police raid gang houses and they find drugs and guns, you should not be surprised. The guns are there as their enforcement. So if we’re worried about guns, then again, that’s a consequence of Government policy choice.”

Police admit that for every dealer they put away, someone is standing right behind them to take their place. And ultimately, as our drug seizure statistics show, prohibition does less than nothing to curb demand.

There are other profoundly negative effects of prohibition. It stigmatises drug use and drives it underground, creating potential health hazards. It puts people in dangerous situations if they wish to acquire drugs. There is no quality control on the type and strength of drug a user buys.

Prohibition provides the only set of circumstances where 20 people can die over three months from smoking synthetic “cannabis” covered in fly spray and weed killer, and the Prime Minister tells the country people need to take more personal responsibility.

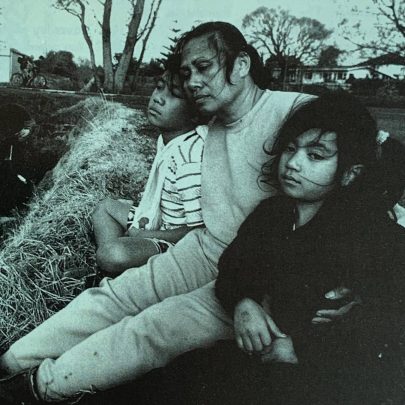

Bell: “The people who are dying are sleeping rough, they’re disconnected, they’re out of work. I’m sure I’m going to get shot for saying this, but if this was 10 kids from wealthy Auckland families, the Government’s response would have been different. Hand on heart, I believe that to be true. If it wasn’t homeless people and it wasn’t young brown kids from Glen Innes, if it was rich white kids from Remuera? We’ve never seen stats like this before, even around alcohol. We haven’t seen a cluster of drug-related deaths like this and the Government’s response is personal responsibility and the police will sort this out. I’m lost for words.”

He’s angry at the politicians and others who support the status quo. “Because it is creating harm. The policy choice that they’ve all signed up for is creating huge problems for this country.”

The often-repeated claim by politicians that “we need to get tough on the gangs” doesn’t withstand logical examination. If we were really serious about getting tough on the gangs, we’d take away their primary source of income and all the power they derive from it. The only argument I’ve heard against this approach is that, “They’ll just find something new to do.”

As Quince says, “Fucking great. Let them. We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

The argument for decriminalisation

Meanwhile, the Government increases spending to enforce our broken laws. One of the largest items in this year’s Budget was $800 million for new prison beds. “Is that the only solution to the Maori housing crisis?” asks Quince. Bell says around 80 per cent of the Government’s response to the drug issue is through the criminal justice system. It’s an appalling waste of money, demonstrably ineffective, and senior police are now admitting off the record we’re not going to arrest our way out of the P problem. Incarceration doesn’t cure addiction. For that, you need treatment and rehabilitation, and education about the dangers of drugs.

Johnny Dow, director at Auckland residential drug and alcohol treatment centre Higher Ground, has a permanent waiting list of 70 people. If he took people waiting to come from prison as well, it would be around 200. The wait to get in is at least 14 weeks. “Around 70 per cent of our patients are addicted to meth. They spend between $300 and $6000 a week on their dependency — the average is about $2000. To sustain a habit at that level, a person has no choice but to be dealing or committing other crime.”

Dow is quick to point out the elephant in the conversation: Higher Ground deals only with the estimated 10 per cent of meth users who develop severe dependency. What the police and the Government aren’t saying is that 90 per cent of the people who use drugs, even highly addictive ones like methamphetamine, will most likely never develop a problematic dependency. They’re perfectly capable of managing their drug use in the same way most people are perfectly capable of having one glass of wine with dinner without needing to crack into the bourbon at 8 o’clock the next morning.

Dow says there is an urgent, desperate need for more money in addiction and treatment services. “If someone has a severe dependency, they need residential care, they need some time out to get well. I know they need more outpatient services available, more family therapy available. Often it’s the family that are really pulling their hair out with this as well. It’s a whole range of services we need to continue to fund and get more money for, because we just can’t keep up with it.” As well as not receiving any new funding, when measured against inflation over the past 10 years, it’s also taken a funding cut of around 10 per cent.

So what are the costs? Incarceration costs us roughly $98,000 a year per inmate. There has been a spectacular blowout in prison budgets every year since 2014, and an increase in prisoner numbers to just south of 10,000 in 2017. It’s hard to get reliable data, but a large number of these inmates are inside for drug or related offending. Former Justice Minister Judith Collins was unrepentant about the cost overruns, telling the Herald in 2016, “People are in prison because they should be in prison.” Total spending in 2017 is marked to be $900 million.

Meanwhile, the Netherlands has decided to focus on health rather than criminal justice, with an emphasis on treatment and working with people in a therapeutic way to address the reason for their offending, including their dependence on substances. Sue Paton of Dapaanz, New Zealand’s association for addiction treatment practitioners, supports this approach. “This is much more effective at addressing someone’s addiction, reducing their likelihood of committing crimes, and enabling them to return successfully to society much sooner.”

The Dutch closed 19 prisons in 2013 because prisoner numbers had fallen after penal reforms, including greater emphasis on treatment and rehabilitation. Five more prisons are being considered for closure. So why does New Zealand think creating more prison beds is still a good idea?

To build another greenfields facility like Higher Ground, which takes up to 52 residents, would cost only $12-14 million, with $4 million each year in running costs. When accounting for the work Higher Ground does with pre-admissions and outpatients, it can help as many as 300 addicts and their families at any one time. Vastly less expensive than prisons, facilities like Higher Ground are also proven to have infinitely better results. In the 14 weeks people are waiting for admission, unless they’re abstinent, they will be using sex work or crime to fund their habits: dealing, burglaries, armed robberies, theft. “It’s the only way they can survive,” Dow says.

Higher Ground’s return on investment is impressive: Dow says when total costs are compared to the estimated benefits, the treatment-centre programme creates value of around $2 for every $1 spent in the programme. This equates to a return on investment of nine per cent a year. Later, Dow has his head of finance forward me updated numbers, increasing the return by a factor of three. That makes the cost benefit to society $6 for every $1 spent. Despite figures like this, current policy is to put most of the money into a system that has failed for generations, financially starving programmes that are proven to be effective.

Dapaanz doesn’t have a position on legalisation. “We do, however, strongly believe that addiction is a health issue,” says Paton, “and that people have a right to the access of treatment and support, and that this should take precedence over punitive measures which are ineffective.”

But Bill English needs to wait for the “evidence” that changing our criminal justice approach won’t create more harm.

The Portugal experiment

The list of countries reforming their drug laws is continually growing, and all demonstrate positive results. The Netherlands, Finland, Bolivia, Uruguay, Colombia, even the arch arbiter of the drug war, the United States. And Portugal, which reformed its laws in 2001.

“Portugal is a truly holistic response to the drug problem,” says Bell. “Lots of countries have decriminalised cannabis, but Portugal is a beautiful model because they said this is a health issue, and not just for pot, but for heroin, for methamphetamine, for cocaine. And we agree with that. So they decriminalised all drugs and then at the same time put their money where their mouth was and committed resources into prevention, education, rehabilitation. They provide tax breaks for businesses employing people in recovery. You look at the broad range of data out of Portugal, and it highlights overwhelmingly what a fantastic model that has been, and how well that’s worked out for them.”

Politicians are always saying “think of the children”, says Bell. “It’s their mantra. But if we do think of the children, then Portugal doesn’t criminalise their young drug users. The beauty of the Portuguese system is it changed the DNA of their society in terms of its approach to drugs. It has removed all the stigma around problematic drug use. More people are accessing treatment. For the politicians who want us to think of the children? Youth drug use went down.”

The impact of the Portuguese reforms has been extraordinary. As well as youth drug use, adult use is also down, alarmist propaganda about it exploding having amounted to nothing. The number of people imprisoned for drug-related offences fell from 44 per cent of all inmates in 1999 — two years before the reforms — to 21 per cent in 2012.

Meanwhile, the number of people treated for addiction increased by 60 per cent between 1998 and 2011, going from 23,600 to 38,000. And drug-related HIV infections have fallen by more than 90 per cent since 2001.

Portugal’s reforms aren’t a complete panacea to the country’s drug problems, but they are undeniably a huge improve-ment on the situation before reform.

Even Chambers is prepared to concede on Portugal: “It’s an active debate and not just here in New Zealand. Certainly we will learn more about how other countries go. Now we have the law as it is, and we’ll just continue to work with that, and use our discretion in circumstances where it’s the right thing to do.”

There’s a headline from the American satirical site The Onion that reads, “Drugs win Drug War”, but the joke is really on us. We’re paying billions in actual and societal costs to support a system of prohibition that has failed by all of its stated outcomes.

To borrow from Shakespeare, it’s time for our politicians to screw their courage to the sticking place, and make meaningful reforms to our drug laws. The injustice caused by our current system perpetuates a great moral wrong.

I’m not hopeful of seeing change without genuine public pressure. But one way to aid progress is to give the government some plausible deniability through a royal commission or similar taskforce looking at the actual effects of our drug laws.

This is probably the only kind of governmental vehicle where the expert voices will be taken seriously. It’s what the new Campaign for Drug Law Reform is seeking. The terms of reference must ensure we find a better solution than jailing or convicting people for minor possession or use of drugs. The status quo is broken beyond repair. “The definition of insanity,” the quote goes, “is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.”

Bell says there is now so much evidence to support a new approach that the onus must go on the supporters of the current system to demonstrate success. “National and Labour talk about sending messages. No one’s hearing your message, because 80 per cent of young New Zealanders have tried illegal drugs. If you’re worried about sending a message, fund drug education.”

Matt Zwartz is involved in the Campaign for Drug Law Reform, lawreform.org.nz

This is published in the November- December 2017 issue of Metro.