Jul 15, 2018 Crime

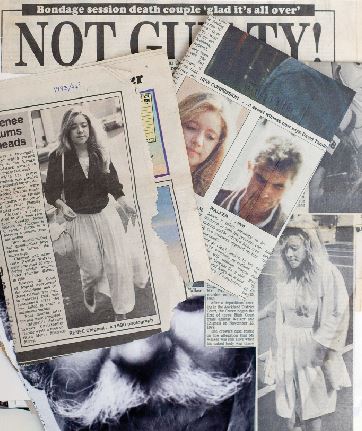

Former teen dominatrix Renée Chignell was once New Zealand’s most infamous woman. Convicted then acquitted of the January 1989 bondage-and-discipline murder of English cricket umpire Peter Plumley-Walker, whose body was thrown into the Huka Falls, Chignell has remained silent about what went on that night and her life since she won her freedom. On the 20th anniversary of one of the country’s most notorious murder cases, Chignell spoke out for the first time.

This story was first published in the November 2009 issue of Metro.

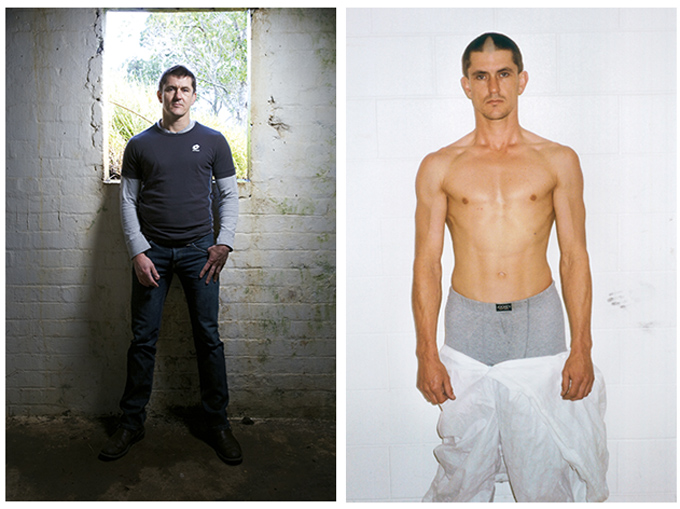

As her elated co-accused and former lover Neville Walker faced a media barrage in the wake of their third, sensational murder trial, Chignell was being driven from notoriety to obscurity.

And there she has stayed, resolutely refusing to talk about her part in one of the most infamous murder cases in New Zealand criminal history, despite media offers of tens of thousands of dollars for her tell-all story.

What a story it was, too, the one that introduced New Zealand to the world of bondage and discipline. The one that introduced the word “dominatrix’’ to the vocabulary of every suburban dinner party. The one that put the hooker in the Huka Falls.

The murder charges were laid against Chignell, the 18-year-old blonde bondage mistress, and Walker, her 34-year-old lover, after the naked and trussed body of Peter Plumley-Walker, 51, was found, bloated and decomposing, six days after the pair had dumped him over the falls.

Police alleged Plumley-Walker was alive when he went into the water, and the pair were convicted at the first trial and jailed for life in December 1989. They successfully appealed, but the jury could not reach a verdict at their second trial a few months later. They were acquitted at an unprecedented third trial, the jury accepting that Plumley-Walker could have died accidentally or of natural causes during Chignell’s bondage session.

To help her escape the media frenzy when she finally walked free just after 10pm on June 14, 1991, Chignell’s lawyer, Stuart Grieve, arranged for prison guards to take her from the High Court holding cells back to Mt Eden Prison to be released there.

But like the rest of Renée Chignell’s life, things didn’t go according to plan.

“I went inside and gave all the staff a big cuddle,’’ she recalls. “Then I went outside holding all my gear. I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m free, I’m free.’ But no one turned up to get me. It was late, it was dark and it was coming on for midnight. I was scared and there were no mobile phones in those days to ring someone. I waited outside for at least half an hour and then had to go back in. It was bizarre.’’

Finally, prison staff called a cab, which took her home to mum.

Read more: Mistress, Mercy docu-drama review: How Renee Chignell herself stole the show

January 27, 1989.

Renée Chignell says she had misgivings about Peter Plumley-Walker as soon as he arrived on the doorstep of the Rotomahana Tce, Remuera, rental townhouse she shared with Walker, where the couple, just a month earlier, had set up their bondage business.

“It was his eyes. He had very intense eyes. I remember feeling with Plumley-Walker that he was more than I could handle, you know.’’

Plumley-Walker was a regular bondage client and she suspected he was into heavier B&D than the “introductory

sessions” the novice dominatrix Chignell was offering. She was too queasy to perform some of the sadistic techniques of more experienced mistresses. Plumley-Walker asked to be punished for what he had done to children, claiming to have abused young girls.

Chignell still believes what he told her was real, and not a fantasy for the session. She thought he was sick. “I had this instinct of ‘I don’t want to be here,’ but it was my home. And I felt because he had paid $170 for the session I had to complete it.’’

Plumley-Walker told her welts and bruises were no problem to him. He wanted to be tied good and tight. He wanted his nipples clamped with bulldog clips, but she wouldn’t do it.

“He wanted me to talk degrading to him. Things like, ‘You’re a filthy boy, kiss my shoe. You’re a bad slave.’ He wanted heavier whipping — he wanted a cat o’ nine tails, but I only had a cat o’ five tails, I believe, a smaller one. He wanted more and more and more. Which I wasn’t there to give him because I wasn’t experienced.’’

Plumley-Walker was naked on his hands and knees as she spanked him with a riding crop. He wore a latex mask and leather gag attached to a ball in his mouth.

When she took off the mask and tied him spread-eagled to the wall, Plumley-Walker wanted a chain dog collar with a slipknot tightened around his neck rather than the usual leather strap. His feet were chained apart, his arms outstretched like a crucifix. By the time Chignell had tightened the neck chain, Plumley-Walker was trussed up tighter than a Christmas turkey. Just the way he liked it.

She told him the words to use if he wanted to halt the session: “Mercy, mistress, mercy.’’

Chignell left the room for a coffee and cigarette with Neville Walker. She didn’t normally leave clients longer than a few minutes, but it was up to 20 minutes before she returned to find Plumley-Walker slumped against his bonds, his face dark blue.

“I freaked out,’’ Chignell says. She screamed for Walker and the pair unshackled Plumley-Walker, to find he wasn’t breathing. “I was probably in more shock than I have ever been in my life. I was crying hysterically. Neville went white.’’

Chignell began administering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while Walker compressed the dead man’s chest. “Plumley-Walker’s lips were blue. I just felt utter, utter dread.’’ She says she regrets to this day that they failed to call the police right then.

“I kept saying to Neville, ‘We’ve got to call the police, we’ve got to call the police…’ I just knew even though we hadn’t done anything wrong, it wasn’t something we could get away with. It’s not like on TV where you can dispose of a body and nobody finds out. But then if we’d rung we could have been sitting in the same situation anyway. It wasn’t like he just fell on our floor having a cup of tea looking at buying a sewing machine. He came here to do B&D and obviously it was odd circumstances, to say the least.’’

Just before 9pm, with Plumley-Walker’s body still lying under a blanket on the carpet of the makeshift dungeon a few metres away, Chignell’s mother arrived with fish and chips for tea.

They’d been saving to go to Australia, but Chignell thought she would go to the airport then bolt home again once he’d gone through the departure gates.

Chignell had left the sex industry when she began seeing Walker, saying she found it impossible to work as a prostitute while having a boyfriend.

Her relationship with Walker, her first serious boyfriend, was almost a mirror image of her parents’ marriage, which was marred by domestic violence until they split when Chignell was 13.

The only child of the marriage, she says her first memory as a toddler was wandering into the kitchen of the Golf Rd, Titirangi, family home to see plates smashed, food everywhere — and her parents locked in combat like the front row of a rugby scrum.

“I thought I could change Neville,’’ she says. He would accuse her of having sex with the Indian dairy owner when she went to the shops for bread and milk. He had a bug installed in the bondage room to eavesdrop on sessions to make sure she wasn’t having sex. When he thought she’d given a customer a surreptitious hand job, he smashed the windows.

“When we got arrested, even though we had this enormous problem we were about to face, I remember feeling sheer relief that we were going to be separated.

“When we got bail, the judge said there was to be no contact, and I thought, ‘Thank God for that. This is my exit ticket from Neville.’’’

Walker still found ways to contact her, even when the pair were in jail. She says he’d smuggle notes over with the inmates delivering food to the women’s section. “Sometimes they’d be quite positive. He’d say, ‘Be strong,’ or ‘I’m here for you,’ and ‘Don’t say anything.’’’

Chignell was to spend about two years in jail — although she was bailed before the first trial, she served most of a two-year sentence for wilful damage to Plumley-Walker’s car, which she and Walker torched a couple of days after the death.

In some ways, though, she adapted well and quickly to jail. Despite being initially petrified that “I was going to be taken to the showers and assaulted with a broomstick and be someone’s woman”, she made the most of her time inside and even describes making a “nest’’ for herself at Christchurch Women’s Prison.

In a bizarre coincidence, she spent six weeks in Mt Eden Prison with her mother, who ran a lunch bar in Queen St but was jailed over unpaid parking fines. “She told the judge to send her to jail because she wanted to see her daughter.’’

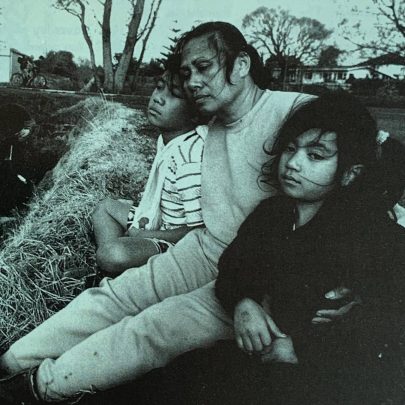

Now living in the Bay of Islands with her grandmother and son in long-celibate solo-motherhood, Chignell works as a caregiver for the elderly, tailoring her hours so she can be home when her 15-year-old boy gets in from school. She helps fundraise for his school sports, is always on the sidelines for games and practices. “He thinks I’m the best mum out of everyone.’’

She’s dieting to shed the kilos gained by a weakness for chocolate, and saving for the $390 laser work to remove a faded dagger tattoo etched between her breasts one drunken night 25 years ago.

Talkative, expressive and bubbly, she laughs readily and chats easily. She rarely swears and has the quaint turn of phrase of a soccer mum — her harshest description is reserved for Neville Walker, whom she describes as “an absolute bugger’’.

Chignell expletives include “Crikey dickens!’’ and “Golly gosh!’’

While she’s happy with her life now, she craves the education she missed by leaving school before the fifth form. In jail she studied accountancy, but after her release, she dropped out of a polytech course in the same subject. She’d enrolled under another name “but I was always waiting for someone to say, ‘Oh, I know you!’”

Now, she thinks she might study psychology — which she reckons is part of what the sex industry is all about anyway.

“I want to be a counsellor working with troubled teens. I seem to have a good rapport with kids, guys and girls. I look at my mother [who died three years ago of pancreatic cancer]; we were friends. But I wish she had put on her mother cap more. A lot of people say, ‘Gosh, you and your son are such good friends,’ but no, no, I’m his mother first and the friendship comes from being consistent and fair. He’s such a good kid — I’m so proud of him.’’

A sporty yet studious, hard-working boy who she says wants to be an accountant as she once did, her son has always been mature beyond his years — except when he was born 16 weeks early weighing less than 1kg.

His father, Stefano, whom Chignell describes as the love of her life — despite their relationship of only a few months — was driving to Meremere to collect car parts for his Onehunga panelbeating business when he was killed by a drunk driver. When she heard he was dead, “I remember blacking out. I saw dizzy stars on top of my eyes and literally fell down.’’

She was 12 weeks pregnant when she heard the news. The pregnancy was unplanned and marked by such severe morning sickness she was hospitalised and put on a drip about seven times. But Chignell always knew she would keep her baby. She has since changed her name to Stefano’s by deed poll.

Motherhood would eventually give her the motivation to turn her life around when she slipped back into prostitution and into drug-taking after her release from jail. The lifestyle led to arrests in 1999 and 2000 on charges of theft and possession of instruments for drug-taking. At the time, she was in a casual relationship with a former Paremoremo inmate whom she’d got to know as a “penpal’’ while she was in jail.

She’d tried hard to go straight after her release, applying for a number of retail jobs, but her confidence was knocked by employers’ rejections when she fronted up about her past. “Old habits die hard,’’ she says, explaining her return to the sex industry.

“I always felt I had one foot ready to walk out the door. Even when I received the money at the end of the night, it felt like it was dirty money in some ways. I felt I was letting everyone down, but mainly myself, by getting back out of jail, doing so well, and then, ‘What the hell am I doing in this scene again?’ I thought, ‘I shouldn’t be here, I should not be doing this.’’’

She was on a methadone programme by the time her son started school, but says she never exposed him to her drug-taking associates. After the February 2000 drugs-related conviction, “I started realising how important family was. I was starting to see my son grow up quickly and I realised I was going to just have to buck up. Step up to the plate. I knew I was a good mother but I was trying to please the wrong people. You have to look after yourself first if you are going to look after other people. If you’re not OK yourself, no one else is going to be OK.’’

Since her on-off relationship with the former prison inmate, there have been no men in her life apart from her son. Sometimes she misses a relationship; mostly she doesn’t. Her life is too full to worry about what it may be lacking.

“I haven’t had sex in years,’’ she laughs, “and I’m not unhappy in the slightest. Sometimes I see couples and family units and think I would love to give my son that family structure, and I know there are times he actually yearns for a father figure.’’

But she says she would never expose him to the risk of fly-by-night men. “I just don’t go to the pub and I don’t get drunk and bring home someone and wake up and am, like, ‘Ohmigod,’ you know? I’ve just never been like that; it’s just totally out of the question.

“I’ve had many people approach me and ask me for dates but I’ve never taken the second step. I’m just not interested. I think there’s a lot of fear there as well, actually, because every relationship I’ve had has ended badly.’’

While she’d love to end up in a happy relationship one day, “I just can’t see it happening for a long, long time. I’m just not out there looking.’’

She says she’s had only about five boyfriends in her life and rejects suggestions she’s ever slept around in her private life. “People think I was this slut when I was younger — I can use the word ‘promiscuous’ but that seems too pretty — but I never was. I had a friend who would literally jump anyone’s bones but I wouldn’t. I used to jump out the window at 13 and 14 and go riding in cars with boys and go into Queen St. But I wasn’t sleeping around. This is why I’ve just gone, ‘To hell with them; people can think what they want.’ Those who matter who are nearest and dearest to me know who I am and I know who I am. If I can go to bed with a clear conscience… I’m fine. So that’s why I’ve always felt I don’t need to explain myself.’’

There have been suggestions she was physically or sexually abused as a child — she was not. But she was confused at the contradictions she faced as a non-Catholic attending a Catholic primary school and having to lie about attending a nudist club on weekends. Her father was the club photographer, and Chignell vividly remembers the pictures adorning his darkroom.

Her father has publicly blamed the marriage split for the adolescent Renée going off the rails, but she says she was relieved at the divorce because it stopped the fighting. She recalls her father always brought her up as a kind of tomboy — the son he didn’t have. “He never called me Renée. It was always Goozer.’’

He took a photo of her while she was still in nappies, and stuck a cigarette in her mouth and beer can in her hand. “He thought that was funny.’’

She was working at Campbell’s Shoes in Auckland when she met the street-walking transvestites — “some of them were absolutely gorgeous’’ — who’d come in to be fitted for size 13 women’s shoes. “I was intrigued as to where all this money was coming from; how they could afford all these things.’’

One of them, Claire, took Chignell and her friend Monique out with him and gave a client a blow job in the front seat while they sat stunned in the back.

Within weeks, Chignell was plying her trade as a street walker off Howe St. Monique was working off Karangahape Rd. To protect themselves, a friend would note car number plates, and they always consulted the Prostitutes’ Collective’s Ugly Mugs list.

“I thought it looked like easy money. I saw easy money, absolutely.’’

She was soon supplementing her $170 weekly wage from the shoe shop with $1000 a night on the street. The money was so good she worked only one night every second week. She saved up and bought a blue Corvette and shopped for gorgeous clothes at the Chrissy R boutique.

She set rules — she went only with older men and only those in smart, late-model cars or business vehicles, and avoided “young men, silly men and drunks’’.

“My first two clients were in their 60s and I felt secure, I felt safe. The first one there was no sex involved. I was with him for two hours in a motel. We had a shower together. We talked and cuddled. There was nothing threatening at all.’’

But one man scared her off the street for months. “He was an engraver with the name of his company all over the side of his van. I thought, ‘You can’t get any safer than that.’ I think I gave him oral sex and instead of the payment, he was going to give me a jewellery drill so I could make shell necklaces.

“I thought I was coming out better off because I’d been to the hardware shop and saw what they cost. It came to the end and I said, ‘OK, let’s do the trade’ — that’s how trusting I was. There was no talk of money earlier because it was icky. He just said, ‘No, I can’t do it.’ Something inside me knew, ‘Uh-oh, get out of here now.’

“He went to lean over to grab me and I just opened the door and fell out, landing on my knees. I was just terrified and panicking. I remember the blood from my knees going through my white dress as I walked up Howe St.’’

Feeling it was safer in a massage parlour, the 16-year-old Chignell started work at Emily’s, under various names including Angel, Zoe and Stephanie. She soon moved next door to the House of Dominance in Emily Place — because bondage and discipline meant she wouldn’t have to have sex.

It’s hard to believe Chignell ever felt she was tough enough for the job. “Some of my clients wouldn’t go with me anymore because I’d give them five whips each side and then I’d be rubbing their bums saying, ‘Are you all right, are you all right?’’’

At Rotomahana Tce, she gave them a maid’s uniform and made them clean the toilet. “I used to have cream for after the sessions to make sure they put it on their bums because I didn’t want them to go home with red welts on them. I remember having a client who wanted blood to be drawn but I couldn’t do it.’’

In fact, she says she found the whole experience of being a bondage mistress “really odd’’.

“I found it quite funny, the dressing up and the nine-inch leather boots — I thought that was excellent, that I could even walk on these shoes — but there was no way I could have taken it to the next step of doing, oh, nipple piercings and scrotum… what did they call it? It’s like men are prepared to pay $400 to have their testicles so squeezed…’’ she stops and shudders. “I couldn’t get into that. And what do they call them, not ‘golden showers’ but they poo on them. Oh, I would never have made it as a dominatrix, never. I had a couple of clients who said, ‘Don’t be so nice, you have to be the mean mistress.’’’

The clients never struck her as pathetic, she says. “Even though they were trussed up looking silly with gags in their mouths and adult nappies on, they still had an aura of… um, what’s the word, not of strength, but of dominance, I suppose. Even though I was meant to be the dominant one, I never felt I was.’’

She was fascinated by the businessmen, pilots, rugby players, “men of standing’’ who made up her clientele. “I really wanted to get into their minds. I was trying to understand why they wanted it. I think with a lot of them they were in high-paying jobs and they had the wife at home who would do anything they would say.’’

She doesn’t believe many women survive the sex industry unscathed. “I wouldn’t recommend any girl go into it. It’s degrading. When you get older, you regret the fact that no matter what you are saving for or what the goal is, you’ve had to sell your body. And even though it’s your body and you can do what you want with it, it’s something you can never take back. Even though you set rules like I did to protect yourself, unfortunately there is the criminal world, there is the drug world… and at the end of the day you are selling a part of you that you can never put a price on.’’

The problem was how to get rid of it when Chignell and Walker’s vehicles were 10-speed bikes.

Chignell told police they went back to the B&D room and tied Plumley-Walker’s feet and hands together and lifted the body into the back of his own gold Cortina station wagon. “Neville suggested the Huka Falls. I had never been there. I cried most of the way about what had happened and what we would say when we got called in.’’

Twenty years on, Chignell says she has no memory at all of that trip to Taupo. She told police that on the way, she started ripping up Plumley-Walker’s clothes and belongings and throwing them out the window. Everything went, including his old-fashioned, brown, English lace-up shoes with the rounded toes.

She told police that, at the falls, they got out of the car and walked over to the water. “I turned around and saw Neville carrying him towards me. We then just both lifted him up and over he went.’’

Today, she says she can’t even remember that, believing she sat in the car while Walker dumped the body. Asked how he lifted it, she says Walker was strong and Plumley-Walker slight. At their trial in December, police would argue Plumley-Walker was alive on the car trip and the couple forced him to walk to the falls before he was bundled over the bridge.

All she remembers, she says, is the roar of the water and the migraine over her eyes.

It was about 4am by the time the couple began the return trip, and Walker had to stop for gas at the Wairakei Service Station — a decision that would put them in the dock when police found CCTV footage of them and the car.

“I’d worked at a gas station and I knew they had the security cameras. I remember going, ‘Oh my God,’ and thinking, ‘We shouldn’t be here, what are we doing?’ I remember having my hands over my eyes and shrinking down in the seat. I remember saying, ‘We’re going to get arrested anyway.’ I just felt it was going from bad to worse to worse to worse.’’

For the first weeks after the murder, when the police were closing in on Chignell and Walker as prime suspects — Plumley-Walker had their address and his B&D appointment time at his flat — Chignell says she felt numb, and an increasing sense of dread.

Jailed after her arrest on February 15, “the enormity of it hit me, bang… ‘Oh my God, I could be in jail until I’m 30.’ It was huge. It felt like the rest of my life, for something I felt was so unjust. People were saying we murdered him, and we weren’t allowed to say anything. When I got to jail I remember just thinking, ‘Why didn’t we do it differently? Why didn’t we make the phone call? Why did I let him put that chain around his neck?’’’

But today, there is also an enduring sense of injustice at how much attention was paid to her private life, given that Plumley-Walker’s death was accidental — and he was revealed as a pervert with a penchant for kiddy porn, whose family had left England when he was threatened with an indecent exposure charge. “I thought, ‘Why is it all on me when this man is like that? Why aren’t we focusing on people like this more?’ I know that seems really quite wrong because he wasn’t on trial, but this was an accidental death. We hadn’t done anything intentionally to hurt him; he had come to us for a service.’’

When INXS frontman Michael Hutchence died in a 1997 accidental hanging linked to auto-erotic asphyxiation — trying to achieve orgasm by hanging — Chignell says she realised Plumley-Walker might have been doing the same thing.

“There were times I could have done with the money,’’ she says. “But we were such a small family; it was the embarrassment of putting them through anything more. I just wanted to get on and forget about all of this. I’m the last Chignell and I felt a deep sense of shame at pulling the family name through the mud.’’

After her third trial, Chignell says, it wasn’t that hard to go to ground. “I just needed some time to feel the grass again. I’m a real nature lover — I can sit for hours and watch birds. I love classical music. I love the garden. When I got out I needed to earth myself again.’’

Now, she says, “I’m just being who I am and being true to myself.’’

But who, exactly, is that? “I’ve got so many different layers. But I’m quite quiet actually and I always have been. Despite the labels people have put on me.’’

Looking back on the case :

Stuart Grieve, Renée Chignell’s lawyer:

“Renée was a young, immature kid who was bemused by this whole thing. From an early stage I realised that her naïveté was such that I would never have risked calling her to give evidence. So in a sense her involvement became irrelevant.

“I had a strong feeling that she was a victim of her circumstances. We saw this photo of her as a baby with a cigarette and beer. I just thought that was terrible. My perception — and it stems largely from that photograph — is that she was not given the nurturing that young kids need. I don’t think I’m a puritan but it really offended me, that photograph.

“After the final trial, I never saw her or spoke to her again.’’

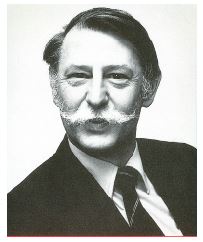

John Dewar:

John Dewar, the detective jailed for 4½ years in 2007 on four charges of attempting to obstruct or defeat the course of justice in relation to the hand-ling of historical sex allegations by Louise Nicholas, was a key figure in the Plumley-Walker case.

Chignell’s lawyer, Stuart Grieve, QC, alleged in court that Dewar “verballed’’ Chignell — introducing incriminating statements by her on his job sheet that she never said. “I didn’t believe what he was saying, I thought he was lying,’’ says Grieve now. When Dewar was disgraced over the Nicholas case, he says, “I was not surprised.’’

Chignell, too, has unpleasant memories of Dewar, saying he hectored her during an interview, yelling at her, “You wanted him dead, didn’t you?’’

“He would give me a leer and many times he’d wink at me,’’ she says. “He was slimy.’’

When he accompanied her to Auckland Central police station in the back of a squad car, she says, he leaned against her and said, “You’re a nice bit of crumpet, aren’t you?’’

“It was terrifying. This was a senior policeman. My eyes just went wide, and in the rear-vision mirror I caught the eye of the constable who was driving. He looked at me and looked away.’’

Dewar, who was released from prison in May, says he “absolutely and categorically” rejects Chignell’s “repugnant’’ allegation. “I would never compromise any interview with such behaviour. If this happened, one would have expected Chignell to have told [Stuart Grieve], and knowing Stu Grieve he would certainly have raised it either at trial or as a formal complaint to police. Quite simply, this did not happen and I have nothing further comment to make [sic].

“Regardless of the truth, you obviously intend to weave this bit of scandalous, licentious crap into your story. No wonder the media is at the bottom of the trust polls.’’

Earlier, Dewar told Metro that Chignell was a very “interesting” young girl whose chronological age “belied her knowledge and experience of life”.

Christopher Harder, Neville Walker’s lawyer:

“Stuart Grieve put a zipper on Renée’s lips from day one. She never spoke a good morning or goodbye or hello to nobody. Zero. Absolutely nobody. It was an absolute wall of silence.

“I genuinely thought I was worldly-wise but I didn’t have a clue about this [bondage and discipline] industry. The first time I heard the word ‘dominatrix’ was when I read it in the paper. I had a real education, which in some regards I wish I never had. Sometimes you get some stuff in your head that you wish you never had in your head.

“It was the highlight of my career; it was the top-of-the-mountain case. It had more publicity and the success blew up the ego. I was obsessive-compulsive about it. I knew something had gone wrong and I wasn’t going to let it go.’’

Les Payn, former vice-squad detective, arresting officer:

“I inadvertently started the dominatrix thing. I took her down to the watchhouse to charge her and when the watchhouse keeper asked for her occupation, she said, ‘I don’t know.’ And she turned to me and said, ‘What am I?’ And I said, ‘You’re a dominatrix.’ She says, ‘OK, yeah, if that’s what you call it. What’s that?’ She’d never heard of the word.

“When I saw it in the headlines the next day, I thought, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?’’’

Simon Moore, junior Crown prosecutor:

“I suppose if there was any impression about Renée it was that she really didn’t know much about what had happened and what was happening. In every sense, other than in the context of this case, she was utterly unremarkable and utterly ordinary and yet she was thrust into the limelight and became the subject matter of every dinner party and every cocktail party on the Auckland circuit for at least 12 months and probably longer. It’s extraordinary, isn’t it?

“But for the titillating aspect of the subject matter, it was really a somewhat unremarkable murder case, although I had underestimated the degree of tension between the sides. It was fraught and difficult.

“Apart from the fact someone died, the whole thing is funny, that in this quiet, leafy, unremarkable little house in Remuera, there was a room which was dedicated to exerting misery and pain on people who were prepared to pay for it. It’s just strange. It’s just silly. Why do men want to have this happen to them?

“I feel sorriest for Plumley-Walker’s family, who have had to live on with that risible legacy of silliness.’’

Ron Cooper, police inspector in charge of the murder case:

“[Chignell and Walker] became quite clearly involved. The video footage at the Wairakei Service Station clearly implicated them.

“Plumley-Walker’s car was burned out but the petrol tank didn’t explode and we were concerned to know whether or not the car had travelled to Taupo because we had his body with no clothing on it in Taupo and his car on fire in Auckland.

“We had the car examined by Environmental Science and Research [ESR]. They couldn’t find any bugs in the radiator or scoria that would indicate travelling overnight or that it had been in that Taupo area around the carpark [at the falls].

“The fire was put out with high-pressure hoses so that wasn’t necessarily indicative. But we siphoned off and measured the fuel and knew the capability of the car in terms of its range.

“We knew if the car had travelled, it had to have been refuelled because it couldn’t make the round trip on a single tank.

“Peter Plumley-Walker used to pay for his petrol by credit card so we had a fairly good idea of his average mileage, and the car had been serviced not long before and the mileage recorded. So although the rest of the speedo was melted, we had the ESR extract it and they came up with a series of options for the numbers. It tended to indicate the car had actually travelled some extraordinary miles [for Plumley-Walker] so that’s why we decided to do an area canvas of the service stations.

“It wasn’t in the hope of getting CCTV cameras — it was to find out if the offenders used their own or Peter’s credit cards to pay for fuel.’’

This was first published in the November 2009 issue of Metro.