Jun 30, 2014 Crime

This story first appeared in the June 2014 issue of Metro.

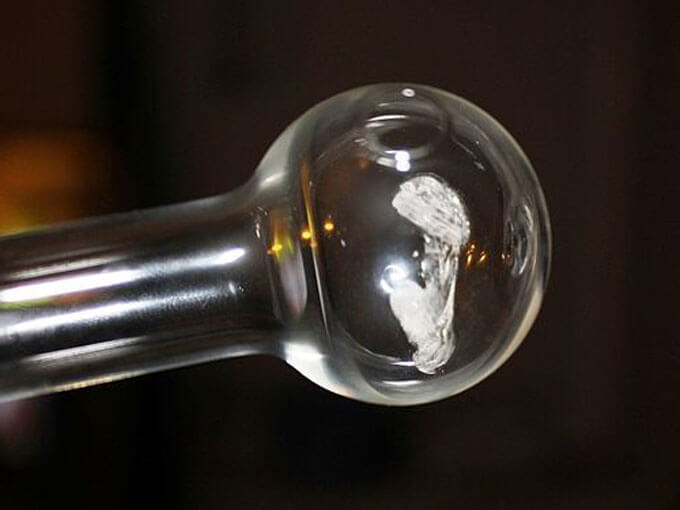

The first time I took P was with a friend in the late 90s. We had no idea. Neither did the guy who supposedly cooked it: our “P” was a kind of wet, burnt gravy in the bottom of a ziplock bag. We were told it was a new kind of speed and that it was going to replace the speed everyone was used to. We attempted the fool’s mission of snorting it, but the brown crystalline paste wouldn’t move from the surface of the plate.

Perplexed, we ended up wrapping a couple of bits the size of a match head in cigarette papers and eating it. We were strung out for about 18 hours. Afterwards, we threw it away. We might not have known about drugs but, like art, we knew what we liked.

My next encounter was about eight years later. By then, the cooks had turned into Jamie Olivers, I was assured by an acquaintance who invited me to a session. We started at 10pm, and the next time I looked at my watch it was five in the morning. We’d done nothing but sit around puffing on the pipe and talking shit for seven hours. The next afternoon, I awoke to the worst anxiety I’ve ever experienced — a horrendously intense, all-encompassing, suicide-inducing agoraphobia that practically paralysed me where I lay. It took three days of solid drinking to get over it.

I’ve never touched P again.

In 2012, the Ministry of Health released the results of a four-year survey on drug use in New Zealand. It found that meth use had fallen from two per cent of the population to one per cent: a drop of some 40,000 users, apparently. This led to Detective Senior Sergeant Chris Cahill telling an Auckland University seminar, “I don’t think methamphetamine is seen very much as a social drug any more. Pretty much the opposite — it’s an anti-social drug. I think society has done a pretty good job of demonstrating how harmful methamphetamine is. I think that has worked. I think we are actually winning. Fingers crossed!”

Reading this, it seemed to me that crossing your fingers was likely to be an ineffectual response to the drug, the people who use it and the world that surrounds it. Anecdotally, I was hearing that meth use wasn’t in decline but had just moved more underground.

The latest police seizure statistics suggest that Cahill may have been overly sanguine. In 2013, police seized 30,976 grams of meth, considerably more than double the 12,503 they seized in 2012. They also seized 833.6kg of precursor drugs, up from the 494.5kg they seized in 2012. Only clandestine laboratory busts went down, with 77 in 2013 compared with 94 in 2012. Does the increase in seizures mean the police are winning, or does it simply reflect an increase in supply?

And if there’s an increase in supply, it follows there must also be an increase in demand. Right?

Assistant Commissioner Malcolm Burgess is unimpressed by the statistics and just as unimpressed at having to do an interview for this story. Kevin, his PR handler, sits in the corner of the small room at police HQ in Thorndon, looking out the window. Burgess fixes me with the basilisk-blue eyes that have interviewed a thousand suspects, and feigns civility. For some reason, I feel guilty.

“There’s lies, damned lies and statistics,” he says. “It’s more about the picture that we’re seeing in our dealing with the groups that are offending, or with particular suppliers. And I think what we’re seeing is a reasonably stable market, not a big swing either way.”

If there was an upswing, police would be seeing some new players?

“There will be new entrants as we take a network out, then obviously others might see an opportunity. Ultimately for them it’s a business. We’re seeing a lot of repeat business — cooks who get locked up, get out on bail, and they get locked up again. A large number of players we’re seeing are of Asian ethnicity, where they’re able to source the product. In the manufacturing part of the business, we’re seeing gang involvement, organised crime.”

He pauses. “So yeah, it hasn’t changed a hell of a lot.”

Burgess isn’t interested much in whether it’s getting better or worse. “We want to be further up the supply chain. We want to be dealing with the cooks and the importers and the people arranging the deals, whether they’re in China or some other part of the world. We’ve focused on the people that are making the drugs, rather than the users. We’d like to think that we’re having an effect, but we’d be mugs if we thought that the ones that we arrested are the only folks in the business.”

Indeed. Operation Ghost, an 18-month combined police and Customs investigation that concluded in December last year, saw police break all their own records. Around 580kg of ContacNT and 16kg of pure ephedrine — the precursors used to cook meth — were seized in a series of raids. Also impounded were 15.5 ounces of finished product, $1.5 million in cash and around $20 million in other assets. Police say the bust was enough to manufacture $172 million of methamphetamine.

(P is sold on the street in grams, but larger amounts are traded in ounces. Police records refer to kilos. We have retained this approach.)

Operation Ghost would seem to have been a very large bust and a major success for the authorities, but it’s little more than a drop in the bucket.

Operation Ghost targeted “a group of senior Asian organised crime figures operating in New Zealand”. Burgess: “A lot of the drug precursors and a reasonable quantity of methamphetamine itself come from Asia. So it’s not surprising that Asian networks will have contacts they can leverage a heck of a lot better than gang member X in the Waikato… But at some point [they] intersect with the wider criminal community in New Zealand, either through needing to find somebody to manufacture, or to supply the drug to the broader market.”

By “the wider criminal community”, Burgess means the gangs. Sources report that all the gangs are heavily involved, but that the Head Hunters, Hell’s Angels and other motorcycle gangs are at the top of the food chain. As recently as last month, the Head Hunters were the subject of raids that resulted in the seizures of $3.5 million in drugs and $3 million in assets, and two of their most senior members facing a list of charges.

Burgess says the gangs are colluding anyway. “They recognise that it’s a business, it can be a profitable business. There will still be crime committed gang on gang — it’s not all light and happiness — but we’re certainly seeing a degree of collaboration to make the business work, regardless of the patch on their back. Not all gangs are going to work with each other but what we’re seeing generally is that, yes, they will, if there’s a buck in it.”

Even given the possibility the police overstate the street value of their seizures — translating 600kg of ContacNT into $172 million seems implausible — there clearly is a buck in it. Ghost would seem to have been a very large bust and a major success for the authorities.

Nope. Apparently it’s little more than a drop in the bucket.

Charles* has been up close and personal in New Zealand’s meth industry, as a user, cook and dealer. Bright, articulate and direct, he agrees with Burgess about who is running things.

“The Asians have the market cornered. [It’s the] price of their pills, which cost them nothing, nothing, and it’s easy to get into the country… They’ve got inside guys that are working the police. They’ll tip off one container load to get two through. And the police think they’re doing a fantastic job. They’re not.”

Charles first encountered P while caring for a relative dying of cancer. “She was on morphine, and to counteract the [sedative effect of] morphine, she smoked P. I had an amount of money, and it was starting to run out, so I bought a large amount of P and got five guys selling it for me so I could keep her going. Towards the last two months of her life, I started smoking it and, having a little bit of intelligence, decided that I would learn how to make it. Shortly after her death, I did my first cook.”

“Any farmer who’s got cattle or horses can get what he needs for his part — and a lot of it’s sent up from Canterbury.”

It wasn’t long before he hooked up with a business partner. “He was a guy that the motorcycle gangs would get to do the work that they couldn’t do. So, him and I got stuck in. We had delusions of grandeur, you know? We were going to flood the market so it would bring the price down. Being in the position where he was my partner, I had a lot of freedom. Sort of untouchable. I could go across all the factions.”

At the height of his operation, Charles sold 26 ounces in one week. “One Friday, I sold 26 grams in an hour and a half. At that stage, it was worth $600 a gram. In a week, I would sell maybe 10 to 20 ounces, wholesale and retail.”

Clean now and out of the business, Charles says he had no problem getting anything he needed to cook. “We had guys breaking into ESR [the Institute of Environmental Science and Research] and getting us glassware and chemicals that we needed. That’s how crazy it was. They broke into it five times in one year.”

He says that manufacturing P isn’t any harder today than it was when he was active. “Really to be organised, and to able to get the stuff? You can get it. Easily. Any farmer who’s got cattle or horses can get what he needs for his part — and a lot of it’s sent up from Canterbury.”

Because of the rebuild? “Not so much. Just the farmers down there realising they can buy something for $137 and sell it up here for three grand.”

He’s talking about iodine, for horses and cow hooves. A kilogram can make about 800 grams of meth.

Farmers, gangs, everyone involved: the methamphetamine market is laissez-faire capitalism at its finest. “The nature of the beast?” asks Detective Inspector Bruce Good from the Organised Financial Crime Agency. “Pure greed.”

Good is more genial than Burgess, but he has the same disconcerting eyes and the same inscrutability. He’s also dismissive of the downward trend suggested by the Ministry of Health statistics. He points at his golf clubs, sitting unused for a long time in the corner of his office, and offers a dry laugh.

“They go and buy brand-new cars with hundreds of thousands of dollars of cash. They love to have flash cars, and they don’t buy them on tick like everybody else does. If you go back to 1997, 1998 where we started to find our first big cooks, they didn’t know what to do with their money. They were buying cars with $20 notes, in shoeboxes. Has anything changed? I don’t think so.”

When police raided the Head Hunters in May, a Porsche, a Ferrari and a Maserati were among the assets seized.

Charles says the risks are high, but the money can be ridiculous. “I was selling ContacNT because the Asians didn’t trust the gangs, because they just can’t help themselves, they’ve got no business sense whatsoever. I had a guy that would collect all the money up from the cooks. He’d haul it up to me, $750,000 lying on my floor. I had counters, check it was all there. I’d put the money in my Asian mate’s car, he’d take off, be back shortly with all the pills. Out of that 750 grand, I would make 100 grand profit, for an afternoon’s work.”

Who’s making all this money? How many syndicates are operating in New Zealand?

“It can come as the cream in the middle of two biscuits, it can come in a Mars bar.”

Good gives me a wry smile, a shrug of the shoulders, an opening of hands. “As soon as we put some people inside, there are some other people who just step into the fray. And you think, ‘Well, what did we achieve?’ We took 500kg off the street. The outlaw motorcycle gangs, they’re quite prepared to let the Asians bring it in here. Customs have a pretty hard job to find it at the border. Whether it comes in foodstuffs, or pieces of equipment, or shoes, or picture frames.

“They’re bringing in finished product [and] ContacNT. We’ve had it come in solid form, like Lego blocks, or disguised in plastic and painted. It can come as ephedrine. That can come as anything. It can come as the cream in the middle of two biscuits, it can come in a Mars bar. It can come as mail, as air freight, in containers, with people bringing it over the border.”

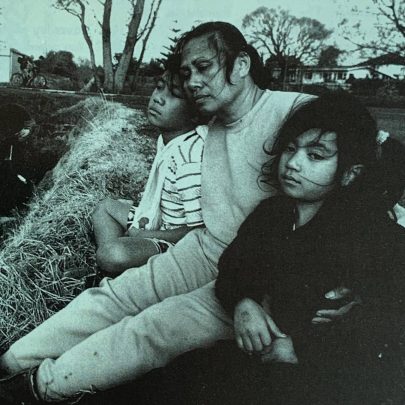

Charles has dealt with most of the gangs across his methamphetamine career, and is not impressed. “They don’t have the brains or the organisation to facilitate anything themselves, so they stand over people. They’re just pieces of shit. They’re brain-dead idiots, who unfortunately have often been brought up in a violent household, and it just perpetuates.”

He says the Head Hunters are sharper than most. “But the Mongrel Mob, and those guys? Out of a gang of 30, there’d be one with a bit of intelligence. Anything they can get for free, they’ll do. It’s all intimidation. But as soon as you turn around and tell them to fuck off, they’re like, ‘What do I do now?’ They’re not going to pull a gun on me… All that’s going to do is bring them troubles.”

Dave is a 28-year-old former cook and dealer, a recovering addict in rehabilitation awaiting trial and a possible jail term of up to five years for manufacture to supply. He didn’t have the luxury of Charles’ connections and the protection they afforded. He refuses to name the gangs he was involved with, a moment of fear on his face as he shakes his head. He thought he could make money from cooking, but he ended up doing it to support his own habit.

“There’d be times when I’d have $10,000 and a big bag one day, the next day I’m asking my mum if I can borrow $20 for gas. And then you’d have the gangs standing over you, wanting ingredients, or finding things out. I lost a lot… knowing how to cook. It’s a bad burden. You’d always have to involve yourself with the gangs, to get ingredients. Or the Asians, who were pretty close, and were owned by the gangs.

“The garage door opens and here’s this guy hanging upside down wrapped in plastic; he’d been there for two days. He was still alive.”

“If you got found out, you’d be in trouble. My family’s been extorted from me supplying sets [of ContacNT] to gang members, and then them wanting more, and I’ve said no. They’ve gone around to my family with guns. You’re always that close to a gang. You either get run out of town, or stood over and extorted. My mum got told she had to pay $200,000, or she’d be paying $20,000 to put me in a hole. And I was a coward, so I just ran.”

Charles says the violence is unavoidable. “Look, I’ve seen some pretty horrific things. One particular day I was with my business partner and his brother, going to pick something up. We were in his car and we pulled up at his garage and he put the bleeper on and the garage door opens and here’s this guy hanging upside down wrapped in plastic.

“He said, ‘Fuck, I forgot about him.’ He was just hanging there; he’d been there for two days. He was still alive.

We cut him down, and my mate said to his brother, ‘For fuck’s sake, what a fucking idiot.’ I know stories of people getting their faces slashed open, their heads caved in, just because people are after their money. This is gangs trying to stand over them, and really stand over them.

“I know of cases where someone has stolen from somebody. My mate… found [the thief], he took him to a farm, stuck him in a bath of water, tied up — and cattle-prodded him for four days till he was lying there in his own piss and shit and vomit.”

Dave: “With transactions going wrong? I’ve seen people get chained to trees for a week, with a bag of meth and a pipe just out of reach, just made to suffer. Just real cruelty.”

Fun times in the meth world. So is methamphetamine an inherently callous drug, or is it that the people involved with it are more callous than others?

“You get to psychosis a lot quicker,” says Johnny Dow, programme director at Higher Ground, a leading rehabilitation facility in Auckland. Just on the hill above the mudflats of the Te Atatu Peninsula, the facility is sited near the end of the road. Past it, there is a turning area or a long walk out into the tide.

“I think it’s an inherently more callous drug,” says Edwin Craig, admissions manager, in a soft Scottish brogue. “The chemical effect in the brain, the withdrawal effects that people get, the psychosis that people end up with. Because they end up paranoid and delusional. Whether or not the users themselves tend to be more violent in nature, you could argue either way.”

Craig says around 50 per cent of Higher Ground’s admissions are still for people with meth addiction. “And that’s been fairly stable for the past three or four years. If you looked historically, our main problem was opiates. We’ve always had alcohol at about half. But opiates have gone down, and meth has gone up.”

Dow says Higher Ground isn’t seeing any decline in the number of people it’s treating for meth. “For the last 15 years, we’ve watched methamphetamine just rise. We’ve specialised in meth treatment, because it seems to be the drug of choice out in the community. Back in the 80s, there was home bake [heroin], number-eight-wire brigade that we are. When methamphetamine first came in, we got a lot of cooks in for treatment, and they were scared for their lives, because they would get kidnapped by the gangs. But as the internet got bigger, anyone could learn to make it. There’s a lot more people making it now.”

Craig says the majority of meth admissions are young men, mostly 18-32. “We often only see the tip of the iceberg, anyway. I read in the paper that the number of meth users had halved. Well, 1 per cent of the population is still 40,000 people. We’ve only got 40 beds. So it doesn’t matter if it’s 80,000 or 40,000.”

“We’re in West Auckland, which is probably the methamphetamine capital of New Zealand.”

Dow is grateful for the government’s methamphetamine strategy, which has seen an additional $30 million available for treatment, but wonders whether this has just helped to lift the lid further on the size of the problem. “We are treating a lot more methamphetamine addicts, because we’ve been given some money towards treating it. It’s been a huge help for this trust, and probably for Auckland’s addiction services. Because we’re in West Auckland, which is probably the methamphetamine capital of New Zealand.”

Dow and Craig hear a lot about why people are using. “Our society is a do-it-now society, an instant society, and methamphetamine is an instant drug. It’s an instant high. I want it now. I need to do this now. And I think one of the attractions of methamphetamine is that it allows people to work enormous amounts, and especially middle-class people, at least at the beginning. Until it backfires on them and they crash and burn.”

And let’s not forget the sex.

Phillip is a 44-year-old addict, also in recovery. He discovered P in Auckland’s party scene, started using on weekends, and ended up using every day. Holding down a $100,000-a-year management job in a respectable company, his addiction was costing him $2000 of his fortnightly $2800 pay cheque.

“For me, it was to have fun. Then it just became so obsessive. It’s the kind of drug that you can just keep going and going. People drink alcohol, and get drunk and fall asleep. But with meth, if you start feeling tired, you just have another puff. The longest I stayed up was for seven days.”

Sex was a big part of that. “I’m addicted to sex as well. I was highly promiscuous. I had a little pad in the city, and it wouldn’t be uncommon to have 20 guys around my place over a weekend, often there at the same time. I had a data projector with porn on the wall. It was just full on.

“I always used to refer to cooks as dirty old men. And I found myself becoming one of them.”

“I’d also go cruising for sex. I’d go down to Western Springs Park; there’s a lot of men there at nighttime. Sometimes I’d spend the whole night there. And then on the internet, that’s why I was up for five or six days at a time. Just hours and hours on the internet looking for sex. Sometimes just on my own, sometimes with other guys, always getting guys coming around, going to their place, hooking up outside, and going to sex clubs. I knew that some guys I’d hook up with were only coming over because I had drugs, because I could afford it.”

Dave says the sex was big for him, too. “Me and my girlfriend would sit down with 10 pornos and have sex all day. You know, with the pipe you can go for lots longer, you can get it up more times, your girlfriend is really dirty, and depending on how you pH [adjust the pH level of the meth during the cook], sometimes you’d give them a puff, and they’d start dripping. You could smell them. That’s how it can become a really dirty drug, you know? I always used to refer to cooks as dirty old men. And I found myself becoming one of them.”

Sophie is another former addict, further along than Dave or Phillip. Sex was part of her addiction, she says, but not the whole story. “I found it wasn’t just about the drug, it was about the whole lifestyle that comes with it. I was involved in prostitution, gangs, it was that whole lifestyle you form. It’s hard to get away from. But definitely, sex was part of it. The sex, the drugs, just all of that madness.

“Meth and sex… I think that keeps people held quite strongly, and they don’t really know how to get out of it. It’s the adrenaline you get from having the drug, all the people that are involved, because you do form some tight bonds. With the working, and the gangs, you just get so sucked into it.”

Dave says that as a cook and a dealer, the opportunities for sex were constant. “I stayed loyal to my girlfriend. I had mates’ girlfriends all over me, but I’d just stay clear of it. It was one of my rules, not to associate with women. Because I thought women would be my downfall.”

He grins at me with his ruined teeth, and we both laugh.

Not everyone thinks New Zealand’s meth habit is as bad as ever. Ross Bell, the head of the Drug Foundation, puts some faith in the Ministry of Health study.

“I think the health data is good. I think the methodology they use holds true when you see what’s happening in the treatment world. I think it works with the narrative that what we’re left with is this hardcore. But if you’re a front-line drug-squad officer and you’re seeing the entrenched users? Then of course you’re seeing that the problem hasn’t gone away.”

“The vast majority of people using a drug, including a drug like meth, aren’t getting into trouble.”

Bell agrees with Dow about the factors behind our methamphetamine use. “If you look at our lifestyle now, it’s work hard, play hard. So what do you want? You need a speedy drug that fits with your lifestyle. If I’m a worker, I’m going to be one of your best performing if I’m on meth, until the chaos happens. It helps you function, 10 foot tall and bullet proof. It doesn’t surprise me that it’s people with hard, busy, stressful jobs who like the support that meth would give them.”

He’s also quick to point out that not everyone who uses meth is an addict. “The vast majority of people using a drug, including a drug like meth, aren’t getting into trouble. You know the percentage of people who form a dependency is only around 10 per cent. So what you’re left with is a lot of people who are, God forbid, using it recreationally and aren’t causing any problems.

That’s kind of the side that people don’t want to talk about because it doesn’t fit with the samurai-sword-wielding kind of nutters that meth creates.”

That would be Antonie Dixon, New Zealand’s samurai- sword-wielding, crazy-eyed poster child for meth addiction. Charles did time with Dixon, and says he was still using in prison. “There’s a group of people who should not touch it at all, because they just lose it. They’re just not mentally equipped. Tony Dixon was one of those people. He sat down with me at the table — he’d been using — and he said, ‘You see those two sparrows flying around here? Watch out for them, mate. One’s the camera and the other one’s the listening device.’ They were just two sparrows that were flying around in the unit. That’s the extent of the psychosis.”

On another occasion, he says, “I heard this thump, bang, bang. So I called the guards and said, ‘Look, Dixon’s doing something to his cellmate.’ He’d picked up the TV and smashed it over his head because the guy had beaten him at chess. This guy came out with bits of his face hanging off.”

Charles says it’s easy to get meth in prison. “They chuck five grams into a wing nut and throw it over the wall. A lot of people have got mobile phones. You say, ‘I’m going to be in Yard Three this afternoon, just throw it in there.’ Inside, say, a wing of 100 people, there’d be six or eight of them still on it full noise.”

Kelly Ellis is Labour’s candidate for Whangarei and a criminal defence lawyer with more than 20 years’ experience. She once described herself to me as “a compliance cost for the methamphetamine industry”. She says current policies aren’t working.

“Drug sentencing is supposed to be about denunciation and deterrent,” she says. “Well, the regime is failing, because few people are deterred. The police strategy on it? I don’t think there is a strategy. It’s effectively prohibition, and I don’t think that prohibition works. The current enforcement regime simply drives the prices up and increases profits.”

“The reality is, we’ve got to start dealing with drugs on an evidence-based approach, rather than a morals-based approach.”

Bell agrees. “We have a very unbalanced approach to how New Zealand deals with its drug problem. We spend more money to police cannabis than we do on all alcohol and drug treatment combined. The first decision government made was to make [meth] a class-A drug. Complicated problem, simple solution, change the letter from B to A. Well, that didn’t solve the problem. Meth use kept going up.

“Let’s make pseudoephedrine a prescription-only medicine. The problem is still here. Let’s give the police more money to bust clan labs. The problem is still here. Customs, new x-ray machines. Problem is still here.

“We sent a delegation with a minister to China so he could talk to the pharmaceutical companies that were making the ContactNT. Let’s clamp down in China to stop it coming. Then ultimately, after all of this supply-control response, let’s put some more money into education and treatment.”

Ellis: “Prohibition doesn’t work. I don’t think New Zealand is ready for wholesale legalisation or decriminalisation, but the reality is, we’ve got to start dealing with drugs on an evidence-based approach, rather than a morals-based approach. We’re not reducing the number of drug addicts. We’re not reducing the supply. We’re not reducing prices.

“Pillorying drug dealers and sending them to jail doesn’t deter them. It puts the prices up and increases the profits. It encourages them. [It] effectively guarantees them a job when they get out. I’m not suggesting I’ve got all the answers. But if a few judges and politicians… tried to keep a straight face in the mirror, then maybe we might be willing to get real about it.

“The reality is all of us could acquire illegal drugs… All of us have got parking tickets over the years, so if we work on the basis that most of us are willing to break the law — we don’t consider the law so sacrosanct that we’d break our necks trying to get to our car before the meter ran out — well, why aren’t we sparking up the P pipe right now? The answer is education. It’s not because of a lack of availability, it’s not because we’re super- law-abiding, moral people. Education is the key.”

Bell says he wants people to be allowed to talk about it. “What usually happens, and we’ve seen it time and time again, is if a politician attempts to talk about doing something differently with drug policy, they get slammed. We [the Drug Foundation] see the problems that drugs cause. We’re not a fan of drugs. Drugs are bad. But the response isn’t working.”

Apparently what does work is when people hit rock bottom and finally reach out for help.

Phillip: “One day I was walking along K’ Rd to an important meeting. My belt broke, I’d put so many notches in it because I’d lost so much weight. It just fell apart. I had not a cent on me so I had to go home and grab a tie, and tie it around my trousers. And then I went to this meeting, which was literally for a multimillion-dollar contract that I was negotiating.

“Not long after that, I contracted syphilis. How I didn’t get HIV is a miracle. I remember going to the sexual health clinic and walking out and thinking, what the fuck is happening to me? I’ve got syphilis and I don’t even have enough money to get a bus home. It’s totally insane.”

Dave: “It took the police to stop me, and I’m grateful for that. If I hadn’t got raided, I’d probably still be doing it. I had all the friends in the world, and after I got raided they scattered. I was turning to people to buy meth because I didn’t want anything to do with cooking it. I was creating myself debts, losing my rent. I ended up living in a tent with my girlfriend. That’s how bad it was. And then I knew: ‘It’s over. I need to get into rehab.’”

Sophie: “I was in an abusive relationship. The guy was just completely controlling, and he was gang affiliated too. I think the drug combined with that relationship was breaking me. He went to prison and I couldn’t stop [using]. I overdosed one night, and the next morning I got on my knees and prayed. Like, I don’t do that. I was just over the way I was living, and I thought there just must be something better for my life. I was on the verge of suicide. But I felt like I was picked up and carried by my God, or whatever it is, and I ended up in the rooms of Narcotics Anonymous.

“I had this turn in myself, where I’m not going to live this way anymore, there’s a better life for me. I saw where my life was heading, with the girls who were beaten by their partners, and controlled, and I thought I don’t want to end up like that. Or seeing the old cooks and their wives and how messed up their lives were. I could see that was where my life would end up being. I was like, actually this is a really sick world to be living in, and I don’t want it anymore.”

Would decriminalisation help, for possession? Detective Inspector Good regards me with near contempt. “You ask that with such a straight face, too. I’ve seen the effects of drugs in many formats on the victims, on the families, from the phone calls you get about ‘my son or my daughter falling off the rails’. I’ve heard the [phone] intercepts of people manufacturing drugs and the callousness they have towards the people [they’re supplying]. The people that are manufacturing methamphetamine in New Zealand learn their trade by going to jail. They probably couldn’t pass NCEA level one, and here they are cooking.

“You go and look at the effects on the mental health, on the hospitals, on the schools. They aren’t going to go away. I’d rather go with education, If you can educate people, that’s better.”

Charles used to call his meth dealing “spreading the love”, but now he is as opposed to the drug as the police. He says it’s an accelerant for everything from burglary to serious violence.

“It’s an evil, hideous infection on the face of society… It’s an absolute scourge. There’s only a small group in society that will use it properly. The rest will do anything to get it, to stop the come-downs.”

Phillip isn’t sure. “If you could control the supply, and the manufacture of it, I would support it. My experience is that making it illegal hasn’t worked. I don’t give a shit whether it’s illegal or not. I still go out there and get it. I think that if it could be done in a way that was more focused on the health benefits or the social good, then that would be good. But I just don’t know how that could work. I know there are other countries where they have legalised drug use, and it hasn’t had all the disastrous effects that everyone said it would have. But I don’t know about this drug. It’s so horrible.”

Read more:

Blow Time: Inside the Cocaine World of Auckland’s Smart Set, by Donna Chisholm.