Jul 11, 2018 Crime

How a homeless salesman’s scheme to flip South Auckland properties and extract rent from unsuspecting tenants along the way has burned banks, investment property buyers and the tenants — and caused a log jam in the courts.

But there are many who say Lau’s been trying to make a killing of his own.

It’s in the mean streets of Randwick Park and Clendon where Lau, a sometime land agent and emerald-level Amway salesman, plies his trade in a series of real estate deals designed to make a buck for both him and the Asian property investors he represents.

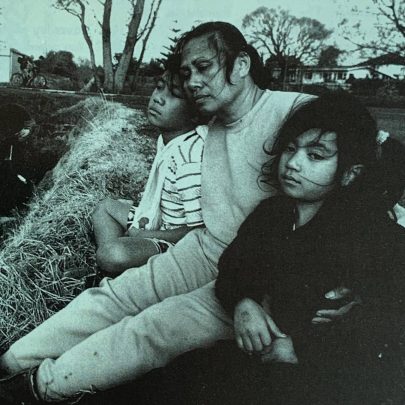

Auckland’s median house price might be around $500,000 but in these parts and in some of these properties, with the holes in the walls, the rubbish inside and out and the toilet pipes smashed by the cops looking for drugs, you’d be lucky to get $200,000. The tenants here are vulnerable. They’re mostly poor, mostly brown and often transient. An average tenancy lasts around six months, before the renters move on — or are pushed out.

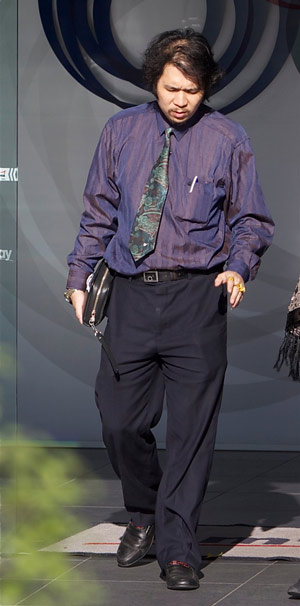

No, Augustine Lau wouldn’t last five minutes here. Not with those long, buffed and tapering nails on his little fingers, the outsized gold watch swinging loose on his slim wrist and three chunky gold rings on each hand. It’s a look at odds with his unshined shoes, the inches-too-long trousers and unkempt hair.

Tonight, he will sleep in his car. Or he may go to SkyCity Auckland, where he says he sometimes gets a free bed because he’s sent so many high-rollers to bet at the casino. He bets there, too, and says he makes about $500 a week.

Tomorrow, he will drive to the High Court at Auckland or the Tenancy Tribunal in Manukau to fight yet another of the legal battles that are engulfing — and gradually sinking — his property investment dream.

There are caveat fights, bankruptcy fights, rent fights, and Lau is in the thick of all of them. Police have been called, trespass orders and counter-orders filed. God knows when he finds time to sell the skin-care products, air purifiers and cooking utensils he talks up on the Amway website.

At the heart of these battles is a complex scam he has masterminded to exploit land-transfer laws and manipulate the court system. On the face of it, it’s a plausible plan.

Lau, aged 39, acts as an agent for 10-15 Chinese and Malaysian clients to whom he says he has family links. He puts deposits on dozens of rental properties in the Manurewa area. He doesn’t intend to complete the sales, but to on-sell the properties before the settlement date. The vendors — also Chinese nationals — are usually already behind with repayments to the bank. They cut their losses and “sell” to Lau for low prices, in some cases less than half of registered valuations subsequently obtained.

Lau says the vendors go back to Asia, although Metro believes many have never come to New Zealand in the first place. He says they return to collect funds to repay any debts owing on their properties, but a less charitable view is that they never intended to pay the outstanding balance of the mortgage. Certainly, those balances usually remain unpaid.

Lau does up some of the properties and organises a sale to a third party, taking the capital gain. His clients never officially purchase the property, and their name never appears on the title.

With no one paying the mortgage on the other properties, the bank soon steps in to recover its debt, and that’s when things get complicated.

Lau’s sale agreement says that if he doesn’t on-sell the property, his deposit converts to a five-year, pre-paid lease. On this basis, he registers a caveat on the property, which he uses to try to prevent it being sold to a new owner in a mortgagee sale.

When a mortgagee sale happens anyway, he insists the lease entitles him to keep collecting rent, even after new owners take possession. And continue to collect it he does — on behalf of his investors.

At least three parties are burned: the banks, which must chase the defaulting mortgagor through the courts for the unpaid loan; the new owners of the properties, who discover the rent is still going to Lau and not them; and, finally, the tenants, who are dragged through Tenancy Tribunal hearings and threatened with eviction because they’re not paying rent to the right person.

It doesn’t sound right and the courts have repeatedly said it isn’t. Mortgage conditions require bank consent before an agreement for sale, and s119 of the Land Transfer Act provides that a lease is not binding on a property unless the mortgagee has consented. That consent is never given in these cases, so Lau’s deal with the original owners is not valid.

But for each property — and its new owners and tenants — it takes time, frustrating court processes and expensive legal bills to set the record straight. And in the meantime Lau keeps collecting the rent.

He argues in some cases his deals are worth more than the bank gets at mortgagee sale and says he is a victim of their change of mind over allowing him to on-sell. As the court orders mount against him, he says he will fight on.

Juanita Maxwell, a Waikato University law graduate, was on her first day of voluntary work at David Rice’s Papakura law firm in late July when Rice asked her to research a case for a client who couldn’t get the tenants at the investment property he’d just bought at mortgagee auction to start paying the rent to him.

The tenants argued their landlord — whose agent was Augustine Lau — had a five-year prepaid lease on the property which trumped the rights of the new owner whose name was on the title.

It could be, Rice told her, that this case might be connected with a High Court fight in April and May this year over a number of property caveats, all involving Lau.

When Maxwell hit “search” in the Lexus Nexus legal database, line after line of Lau-related cases popped up on screen.

For a 23-year-old who’d almost topped her class in the notoriously difficult land-law papers, it felt like a rain of coins from a poker machine.

Something, she knew, was going on here. But what was it?

In 2010, he believed the post-Global Financial Crisis property market was ripe for good deals at low prices.

Lau makes no secret of the fact that when he went trawling Trade Me and newspapers for properties, he was looking for sellers in distress. With the GFC into its second year, they weren’t hard to find.

Enter Taiwanese property manager Hsiu-Yun Ting, who advertised houses for sale in a Chinese newspaper. The properties were all South Auckland rentals, with Maori or Pacific Island tenants, owned by Chinese clients based overseas.

“I told her all the properties advertised were in a rough area and she told me she got a husband who is Maori background — Glenn Folau,” says Lau. “She told me Glenn can look after the property because he’s Maori. Maori-Maori easy to communicate.”

Lau, on behalf of his investors, offered 20 per cent cash deposits on 20 of these properties. But there were conditions: a long settlement period of six to 12 months, and immediate possession. And immediate income from the tenants’ rent.

Then came the clause that has triggered the current raft of lawsuits: “The paid deposit can be converted to five years’ rent/lease if the vendor cannot provide clear title on settlement date.”

As Ting signs up tenants, whose homes she already manages, to new agreements in the names of Lau’s clients, Lau begins collecting the rent — payable to his company, Jesus Co Ltd. He says he starts doing up the properties — perhaps a lick of paint and a few repairs — and preparing them for onsale. But with the real owners now in default on their mortgage payments, the clock is ticking towards mortgagee sale. Legally, he has no more status than a cuckoo in the nest: none.

As the mortgagee sale looms, Lau and Ting do everything in their power to put off potential buyers, hand-painting signs warning them of the lease and saying the tenants cannot be disturbed for five years. Ting tells the tenants not to allow would-be buyers to inspect the properties.

Every legal decision in these cases so far insists Lau is flouting the law. In May, Associate Judge Tony Christiansen said: “There appears to be a careful design by interests connected to Mr Lau to obtain control of a property for an extended period by a process intended to frustrate the right of a mortgagee bank to access its security to effect repayment of its loans.”

But tenants have told Metro that at the time of the sale and for weeks afterwards, they believed Ting.

Beverley and Malcolm Taiapo, who signed a tenancy agreement on one such house in Melleray Place, Randwick Park, just a week before its mortgagee sale, said they asked Ting about the “for sale” signs when they finalised the contract. “She said, ‘No no no, that’s all finished now,’” Beverley Taiapo, a supermarket checkout supervisor, says.

They signed on June 4 this year and a week later, the property’s new owner arrived to tell them he was now their landlord and they would have to transfer their rental agreement to him. They refused. Malcolm Taiapo says he abused the new owner and told him to leave the property.

Thereafter, whenever the new owner turned up, the Taiapos would call Ting, Ting would call the police and the tenants say a “screaming match” then ensued between the parties. “It was stressful and embarrassing,” says Beverley Taiapo. “The whole neighbourhood would come out.” Police confirm having attended incidents at the property.

For three months, the Taiapos continued to pay rent to Lau, until the new owner gained an eviction notice. It was at this point that the Taiapos realised the new owner was telling the truth and that Ting and Lau weren’t entitled to the rent.

Several times, adjudicators have criticised her and her evidence. She has been ordered to pay one tenant $1500 in exemplary damages for harassment.

The female tenant told the tribunal that Ting had yelled at her, phoned her at all hours, threatened her, fondled her breast while she was on the phone at home (saying such large ones would be admired in China) and even interrupted a Child, Youth and Family meeting the woman was attending.

“It would not be extravagant to describe Ms Ting’s pursuit of [the tenant] into the offices of Child, Youth & Family as ‘stalking’,” said the adjudicator. “Ms Ting has consistently displayed highly unusual behaviour in the course of giving her evidence and in her demeanour in the tribunal. For a mature adult, she has shown remarkably little control of her impulses, continually interrupting and attempting to dominate the proceedings. The behaviour reached the point where, after warnings which she did not heed, I excluded her from the hearing for 20 minutes.”

The adjudicator said Ting’s behaviour corroborated the tenants’ allegations. “I therefore find the facts, bizarre as they may be, are as alleged.”

Metro has examined more than 30 tribunal findings involving Ting, including four which found she had not lodged the tenants’ bonds with the government’s Bond Centre, as required by law.

In another finding, involving the tenant who was harassed, the adjudicator did not accept as genuine the tradesmen’s invoices Ting produced to prove repairs had been done on a property. “Ms Ting’s documents do not look convincing at first glance, and the closer one looks, the less convincing they become.”

Ting had yelled at her, phoned her at all hours, threatened her, fondled her breast and interrupted a Child, Youth and Family meeting.

The adjudicator found the invoices were handwritten on forms obtainable from a stationer, dates had been altered, and the writing in two, purporting to be from different companies, was the same.

Two invoices, also purporting to be from separate firms, had serial numbers only two numbers apart.

The adjudicator said the issues were raised with Ting, who had “no explanations to offer”. Intriguingly, a title search shows this property was once owned by Lau.

Lau said he sold it in 2004 to Ting’s sister and they had never met at that stage.

Lau and Ting have even gone to the tribunal to insist that the tenants on the properties sold in the mortgagee auctions must pay them rent under the lease deal — and have tried to evict those who’ve transferred their payments to the rightful owners. They’ve lost here, as Lau has lost in court.

Says one tribunal order: “The entire circumstance of the purported creation and existence of the lease and sublease smacks of sharp practice on the part of the mortgagor acting in collusion with his/her nominee in a last-ditch attempt to thwart the mortgagee and/or subsequent purchasers of the property for valuable consideration with an unregistered lease.”

One of the few home buyers who agreed to talk to Metro — others declined to speak on the record for fear of retribution — is Mark Robertson, who bought a Lau-tenanted house in Redcrest Ave, Red Hill, in a mortgagee sale in December.

He says Lau did everything to try to put him off the deal, including producing a master builder’s report estimating that the property needed $44,000 worth of work. His mother, who was originally financing the purchase, says she was seriously scared by the report. Her son, however, who formerly owned a building company, wasn’t so easily convinced, and put the repair bill at around $5000.

When Metro rang the number given for the builder in the report, Augustine Lau answered the phone. He later said he’d helped the builder on a number of projects in the past — Lau says he’s done part of an engineering degree — and the builder gave him the phone. The builder did not respond to a message left at his office.

Robertson and his mother had to go to the Tenancy Tribunal to support their tenants, whom Lau was trying to evict, and to claim back their rent.

He says from 2009 to 2011, he was able to get the banks to consent to releasing the mortgages on the properties he on-sold before the settlement date.

They weren’t consenting to releases on most of the properties she managed, but he didn’t know why. It might be that the banks stopped agreeing when they realised how many such deals were coming through. Or, as Lau argues, they figured that in an improving market they’d make more money in a mortgagee auction than he was offering.

The lending banks and their solicitors wouldn’t talk to us about the Lau court cases. This year, they’ve been in court numerous times on matters related to him: to lift caveats, seek bankruptcy orders against one of Lau’s clients — his Malaysian-based aunt — or to strike out his counter-claims. There have even been hearings over Lau using his power of attorney to argue his investors’ case. After initially giving him latitude to appear, judges have now lost patience and told him his investors must get a lawyer.

In the early 2000s, Lau had power of attorney for a group of Asian investors who wanted to buy properties here and, he says, to then gain residency. Lau bought about 40-50 properties for the group and borrowed $20 million from banks including ANZ, ASB and Westpac.

The banks, suspicious of the young real estate agent and his deals, referred him to the Serious Fraud Office for investigation. Though Lau says that in 2004 the SFO found no grounds to charge him, the banks decided they would no longer lend to anyone he represented. (This is why, in the latest scheme, his investors didn’t apply for any bank loans.)

When immigration rule changes in July 2003 made it more difficult for his investors to move to New Zealand, Lau says they cut their losses and sold all their properties, losing about $2 million.

It is from transactions during this period that Lau twice came to the notice of the courts. In one case, he was agent for an overseas investor the ANZ sued for $302,000 unpaid on a loan, and in the other he and his then wife became embroiled in a scrap over a 2003 agreement to buy a 202-hectare, $2.5 million Canterbury property.

Both cases provide the first evidence of Lau’s modus operandi — including complex counter-claims to thwart the banks and unconvincing arguments to support those claims.

In the first case, his client claimed he had actually repaid $200,000 more than the bank records showed, but neither the client nor Lau could produce any evidence to prove it.

Lau told the High Court the SFO must have taken the records when he was under investigation. Noted the judge: “Ultimately, Augustine Lau was driven to say his office had been burgled and that was when this record must have been stolen. Indeed, that this might have been the purpose of the burglary. That is outlandish.” He later commented, “As to the principal issue, I have already found Augustine Lau unworthy of belief.”

The second case was finally decided by the High Court in 2007. The decision says the property was one of three Lau bought on behalf of Chinese investors at the time. In all three cases, the prime feature was a deferred settlement date.

The two other properties were onsold before settlement, which, the court said, was Lau’s intention for all. “His principals had no interest in farming the property. They were looking for capital gain.”

But when Lau’s then wife, in whose name the Canterbury deal was done, couldn’t settle on the due date, she lost her deposit of $303,000. The couple unsuccessfully counter-claimed, saying the seller had misrepresented water rights issues.

Undeterred by the setback, and now single, Lau was ready for another foray into the property market just two years later.

But he says he’s suspicious of many aspects of the deals — not least because all the caveats are lodged by very small law practices with just one or two, usually Asian, solicitors. To him it suggests a deliberate choice.

Metro asked Aucklander Tim Jones, convener of the New Zealand Law Society’s land titles committee, to review the cases for us. He was worried by what he saw and is writing to the Registrar-General of Lands, whose office monitors and audits land dealings, for an opinion.

“It’s certainly a fraud on the banks when [the vendors] take their 20 per cent [the cash deposits Lau pays them] and go for a runner, because that money should go to the bank first. It’s not theirs to take.”

Jones says Lau has only to collect rent to which he’s not entitled for a few weeks on a number of properties to make the arrangement lucrative.

“I’m not an expert but I think it smells of scam-type behaviour. I have a suspicion when this sort of thing happens in volume like this, there is someone taking advantage of somebody and it’s either a scam on the bank or a scam on these poor owners and/or tenants.

“I’m worried a little about these tenants. They’re like spinning tops. I’m surprised the Tenancy Tribunal hasn’t joined the dots and started putting someone in to investigate this.”

At the very least, Jones says, Ting has to be held to account for her behaviour.

He’s also concerned some of the law society’s rules around caveats may have been flouted. Lawyers are required to certify that they are confident their clients have the legal right to ask for a caveat.

Lau is no longer working as a real estate agent. He says he left Ray White because of the “conflict of interest” involved when the court cases began to crop up. A company spokesman says Lau was asked to leave because they knew nothing of the deals he was doing.

Lau remains convinced that if he argues the toss for long enough, the courts will eventually see his point of view . “This is justice. You need to keep on going, like the gays and lesbians. Twenty years ago, they say go to jail, they’re no good.

“This country is a very funny country. If you keep going for five to 10 years, you’ll get it right. Like Maori and the water rights.”

He says his clients continue to have faith in him. “They understand the banks are cheating everybody, by changing the rules.”

Ironically, he has no plans to buy a home of his own anytime soon.

“Why should I? A house is a good investment tool, but it’s not good to buy it to live in. Just rent it. If you stay in it, you won’t get your money back.”

This article was first published in the November 2012 issue of Metro.