Aug 19, 2018 Business

Metro’s founding editor Warwick Roger died last weekend at the age of 72, and his funeral will be held today. Under his tenure, Metro broke ground as New Zealand’s first glossy mag and became a strong, investigative read.

Bob Harvey knew him better than anyone. In this piece from 2006, he looked back at his time working with Warwick – the editor who was both feared and revered.

Chamberlain knew someone he thought could be sucked out of the Auckland Star, someone who had written pieces for New Zealand Runner named Warwick Roger. And so over a Cajun dinner in Ponsonby Road, Chamberlain convinced Warwick to throw in his 9am to 5pm job at the dying Star and to edit the new Auckland-focussed magazine. Not a tabloid or a newsprint like the damned Eve, and Thursday, or Alistair Taylor’s pretentious and short-lived New Zealander. This was going to be something ground-breaking and different.

Chamberlain would play publisher, Palmer and his mate, a marketer from British Paints Clive Currie, would find the dosh and Warwick and William Chen, a young designer, would do front of house. The agencies loved the idea and they were important because they would bring the stylish advertisements. And so Metro was born.

‘An editor in every sense of the word’

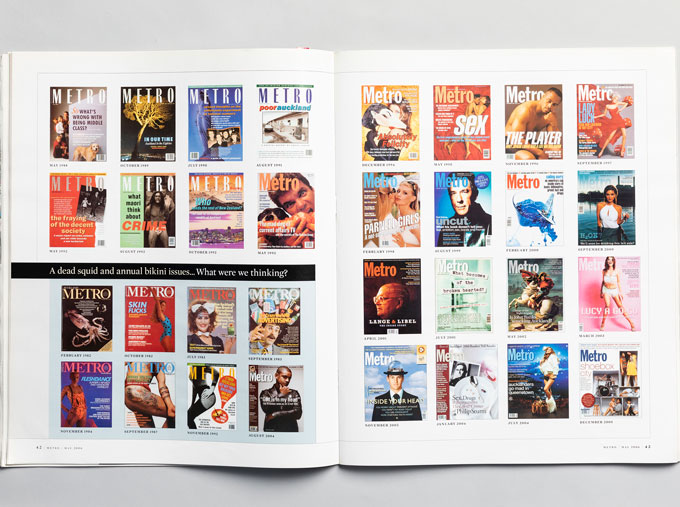

Warwick was a perfect fit. He was the right choice. Like Esquire’s famed Arnold Gingrich or The New Yorker’s William Shawn he was an editor in every sense of the word and he was everything to the magazine he helmed. His editorship would be tested within the first two issues. With the sniff of success came to-do. Chamberlain was dropped as publisher and the first of many lawsuits around ownership that would close ranks and cause backstage drama and a management cone of silence, took place. Warwick kept out of it – drama wasn’t his style or desire. The first Metro issue – with its big stylie ONE cover line designed by Chen who stayed at the magazine for more than a decade – offered a look into Auckland’s most exclusive kitchen, an article on the Samoa House and insight into the VCR boom. It was avant-garde and refined and it was a huge success, literally walking off the shelves. By issue five they had signed up their 1000th subscriber and celebrated with a breakfast at Melba.

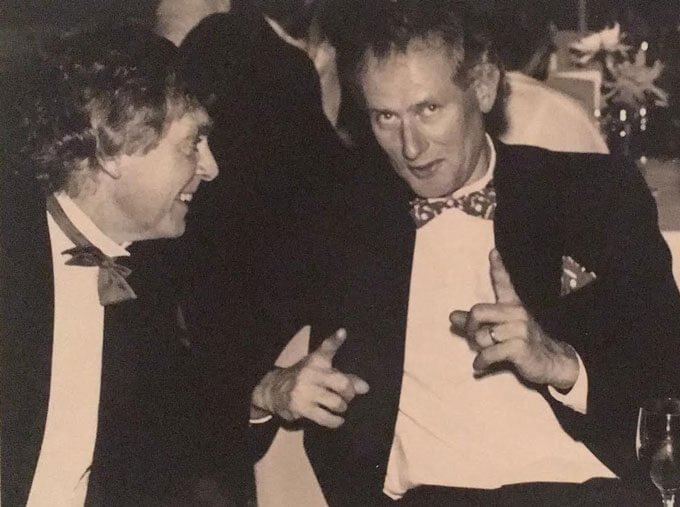

I’d met him when he was at the Star. I worked in advertising and part of that included working on election campaigns for people like Auckland mayor Sir Dove Myer Robinson. During the last hurrah at the home of his niece and substitute mayoress Barbara Goodman, I noticed a young journo sitting quietly in the lush surroundings. I thought he was capturing everything – Robbie’s raving, the fawning staff and family around this great old politician. It was the slim and alert Warwick Roger. We got talking in the garden and we agreed that Robbie was driven by ego and ideas. Warwick seemed to have a grasp of the man, and I felt he had an emotional intelligence which I warmed to. We changed the subject to running and I told him I had read some of his writing in New Zealand Runner magazine. At the end of the afternoon I thought I liked Warwick Roger very much.

As editor, Warwick’s job was to find new fledgling writers. He remembered me and that I’d written an article about swimming the Dardanelles. I’d always seen myself as more than an advertising copywriter; someone who might just be able to craft something that wasn’t 30 seconds long. Warwick rang me and I felt as elated as if The New Yorker had accepted one of my stories. I told him I would like to write about somewhere I knew well – the west and the vineyards. I brought together a tale of touring the tasting sheds and the sixty-three wineries that dotted the west in those days. Warwick loved the story and changed only a few words. I was then commissioned to write an article on the rising fad of bakeries and cafes in Auckland. Our close working relationship had begun and the first seeds of great friendship sown.

It didn’t take me long to hit my stride with Warwick and I enjoyed not only what I was doing but our meetings and talks about running and books. I don’t think you can become an editor unless you read and Warwick Roger read. The books we liked such as Richard Ford and Capote, Esquire magazine and, of course, The New Yorker became the basis of our friendship. To write for Metro and to see your name on the masthead was a badge of honour and one I was particularly proud to wear. Warwick had antennae that would reach out and feel what was going on in Auckland in the 1980s. He was fascinated by the rise of David Lange and we all had lunch at the White Heron Hotel one day. Warwick was brilliant. He charmed Lange and we both agreed he was right for the leadership of the Labour Party. It was Warwick who suggested the great campaign song Up Where We Belong and our friendship with Lange deepened and moved us to political heights. We talked strategy and how to groom Lange to fit an Auckland audience. That’s what mattered and when Lange became Prime Minister Metro’s cover story crowed The Selling of David Lange – how a fat man was made into a Prime Minister.

I’d deliver a story and then wait for the call, heart racing. Warwick would call and we would meet, have lunch, and he would tell me what he liked in the story and what he didn’t, I felt I was special. People who worked for Warwick said I got favourable treatment. Sometimes his mood swings would be difficult to read. He could be a bastard to people he liked and I knew that was true because so could I.

Warwick could never stand mistakes and insisted on a high quality of journalism. Reporters were ordered to deal without fear or favour and if they left a trail of woe in their wake so be it. Former Metro writer Carroll du Chateau told me Warwick jokingly threatened to fire her once because Doug Myers was so pleased with a story he sent her three dozen red roses. Story subjects were not supposed to be pleased.

It was unforgivable to deliver copy that wasn’t well researched. Warwick wrote grumpy letters to his staff berating them for their mistakes. If a mistake had somehow got past Warwick and the subbing team and Metro hits the newsstands with something that was incorrect Warwick would be apoplectic and stony silence would follow. Warwick also insisted that everything was on the record and that all observations would be carefully recorded and included in the copy.

The fearsome Ferret

Metro got better – bigger and more investigative, hitting nearly 300 pages. It was a serious read. Inside the engine room was the Ferret, a brilliant idea conceived by Warwick and his cronies. It soon became the most read and feared column in New Zealand. The regular victims who appeared had code names and monikers. We all contributed by bagging friends, enemies and of course ourselves. Warwick called me Sir Robert, my wife Lady Barbara and always greeted me with the words “has she left you yet”. I would reply “no but it’s imminent”. And we both laughed.

But the Ferret wasn’t just funny. It rampant savaging of throats and nuts was a ticking time bomb. It was a clawed rodent that I believe hurt Warwick and took away his confidence and courageous edgy style. A damaging Ferret remark about the journalist Toni McRae ended in a protracted and fraught lawsuit and that stewed his brain. The Ferret was culled, and Warwick became mellower and less willing to take risks.

When Warwick left his first wife our friendship moved into two halves. Lady Barbara supported Ann and I supported Warwick. I’ve haven’t seen Ann since. And so we stopped being families and I kept writing for Metro. It was the way I wanted it. Being loyal to Warwick was the choice I made. I went solo to his wedding to Robyn and I watched his new family grow.

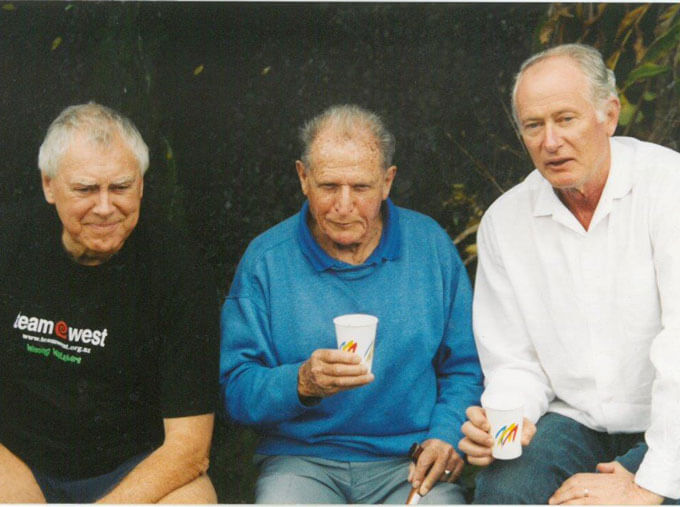

We started having men’s lunches and once a year, in the middle of winter, we would make our famous run and plunge into the icy sea no matter how cold, always followed by a great man’s breakfast cooked by Robyn. Every Easter we would run down from Anawhata Rd through the tracks and streams, kids racing ahead, labradors barking and leaping madly, to fall on the grass at the bottom eating sandwiches and drinking beer. They were highlight days.

Warwick and I would talk about creating new storylines and we hit on the idea of a series around the joy and pleasures that surrounded us and our lives. I wrote the Joy of Fatherhood (which I would later turn into a book called Hey Dad illustrated by Tom Scott), the Joy of Swimming, the Joy of Dogs and the Joy of Friends. He wrote the Joy of Running. We crafted the stories using interview material and personal experiences. It was a great success and I wanted to do more and move into edgier journalism and I knew Warwick would support the change.

I remember drinking one night in a bar when it occurred to us that every man in the place knew more about each other than any woman. It was just the way we were and we talked about a series that Esquire had been prepared to run. I suggested Metro should break a few taboos as well. As Ruskin said, “taste is the only morality”. I told Warwick I‘d like to push the boundaries and take the piss out of New Zealand blokes. “Shall I do the Joy of Onerism and would you run it on the cover?”, I asked. Warwick lit up and said, “why not?”.

And so I embarked, albeit cautiously, on the story of the last taboo, by interviewing guys who had been in jail, on boats, been booted out by girlfriends or wives or who were just plain lonely. I talked to ex-nuns and priests about this forbidden subject. I reported in with glee to Warwick that the story was going to be a ripper. Indeed I thought it would probably either make me the country’s best essayist or condemn me forever. But then, just days before delivery, I got a call from David Lange’s office saying I had been appointed to the Film Commission. I felt my planned essay might just damage me. Suddenly I wasn’t just an ad man anymore. I was going to be a public figure and on a stage with no room for a wanker.

I told Warwick over a beer I would have to join the ranks of those such as Truman Capote who had been promising Esquire a new work for 20 years and Kerry Hulme whose sequel to the Bone People was also endlessly pending. I think he was bitterly disappointed. I had an obligation to deliver, it was fun and I felt I’d got it right. I just couldn’t do it and Warwick’s standard greeting changed from “has she left you yet” to “Where’s my story?”. To be honest I had no answer.

From the first Metro issue dated May/June 1981 to 1992 the magazine soared under Warwick’s leadership. The masthead bloomed with great contributing writers – Michael King did books, Bruce Jesson politics, Hamish Keith downtown, Tim Harris wine. Our late beloved friend John Davis did fitness. Robin Morrison was commissioned to do fantastic photo spreads. Chen was in full stride, though never in favour with Warwick. God knows why because his layouts and design were stunning. The senior writers, who would later go on to pick up every media award going, were Carroll du Chateau, Nicola Legat and Jan Corbett. Georg Kohlap was ruthless with his On the Town paparazzi-style images.

Inside Metro Warwick was both feared and revered. I wondered if his barbs and his manner simply put a barrier up between him, his genius and his perceived and private persona. But he seemed either unapproachable or unwilling to engage. A bloody pity.

Changes

Metro moved around Auckland in offices both overcrowded and absolutely pumping and charged with energy. Nothing has come near it for its hub of creativity, good journalism, gossip and rumour and sheer fun. When Metro was sold to ACP in the mid-1980s it all changed. The culture of ACP was glass, steel and order. And bosses from Oz. The Packer team demanded results and covers that sold. Curries and Palmer exited and Warwick kept his shares which couldn’t have been a bad thing. Inevitably it was time to move on so he went across the hall to the highly successful North & South Magazine and continued his extraordinary run of in-depth and deeply felt essays.

After Warwick’s move to North & South we continued our lunches but Metro had faded from our conversation. With new editors and new direction it never seemed easy and to be honest it never seemed right. We never talked about it or his diagnosis. I did ask him whether people in the office, that huge endless floor of screens and hubbub that made up the ACP stable of mags, approached him for advice, mentoring – proud to show this great editor some of their work. He said no they didn’t. I always found this strange because in the best magazines the former greats like Harold Ross, William Shawn and Diana Vreeland were revered by young and aspiring writers. But Warwick sat alone, working independently as his ship moved away from the shore.

Warwick’s Metro years were astonishing in their courage and acumen. His opinions were I felt valid, forthright and never shamed. I felt he knew the pulse of this city and when I campaigned for the mayoralty I used to quote from his stories summing up the west, the way he brought together the old Dalmatian names, the roads in Oratia and foresaw a west that was a mixture of old and new. And as I read the lines I felt a charge of emotion because I was reading someone who I was close to and who understood me, my community and my humanity.

Over the years our friendship’s grown and changed. The last few years have been lunches of fish and chips and a shandy. We’d call it a man’s lunch and we’d do it often but never as much as I would like. The conversation stays as it’s always been – around books, magazines and who is writing and who is being paid for sitting on their arse. We both bewail the fact journalism is cheap and shoddy. Warwick’s battles with the Herald are over as indeed are his battles with most of his enemies. They are either dead or in rest homes. And that’s a pity because I think Warwick thrived on them. There’s something in this man that likes to be like Hunter S Thompson – slightly unapproachable in his purity of thought and work.

To me, Warwick has been a guiding and unparalleled inspiration and will stay always in that hallowed space in my life. If the swims and the runs are no longer possible as his Parkinson’s disease progresses we will spend our time in the silent space of friendship and memories. No matter what people think of Warwick Roger he is and always has been his own man. He’ll make his own friends and by god, he’ll make his own enemies. So be it. And he’ll live with the results. And die with them also.

This article first appeared in the May 2006 issue of Metro.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the weekly e-mail