Jun 1, 2021 Society

Is this government a once-in-a-generation opportunity lost?

Two months before the election that would make her Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern was travelling in a taxi when she received the most important message in her then nine-year parliamentary career: Labour’s poll numbers were crashing, hitting a historic low. Text messages and phone calls flew back and forth. The party was polling in the low 20s and then-leader Andrew Little went live on television and, whether deliberately or accidentally, said he was considering resigning. The media took the declaration by the throat, putting it to the then-deputy leader Ardern: will you step up?

What distinguishes Ardern from the politicians who nip at her heels is that when the media, caucus and the then-leader were handing the top job to her on a plate, she was reluctant to take it. In the Labour leadership race in 2013, she stood as Grant Robertson’s deputy. In 2017, she was the unfailing loyal deputy again. Ardern took the job only when external forces were irresistible — catastrophic polling, a leader who had lost his confidence, and a party desperate for her “stardust” — agreeing to take Labour to the election out of a sense of duty rather than ambition.

This might seem like a roundabout way to begin criticising the government’s housing policy, but it’s essential to understanding the Prime Minister’s personal and political character. Whereas Helen Clark, and to certain degree John Key, would impose their will on the Cabinet and caucus, Ardern is a consensus politician. She plays it safe. The parliamentary term 2017–2020 is notable, if anything, for the things that never made it through, from capital-gains tax to KiwiBuild. On the former (CGT), there wasn’t a consensus within the government or the private sector, so Ardern took it off the table. On the latter — the plan for 100,000 KiwiBuild homes — there wasn’t the skill or the scope within the government or the private sector, so it was gone as well.

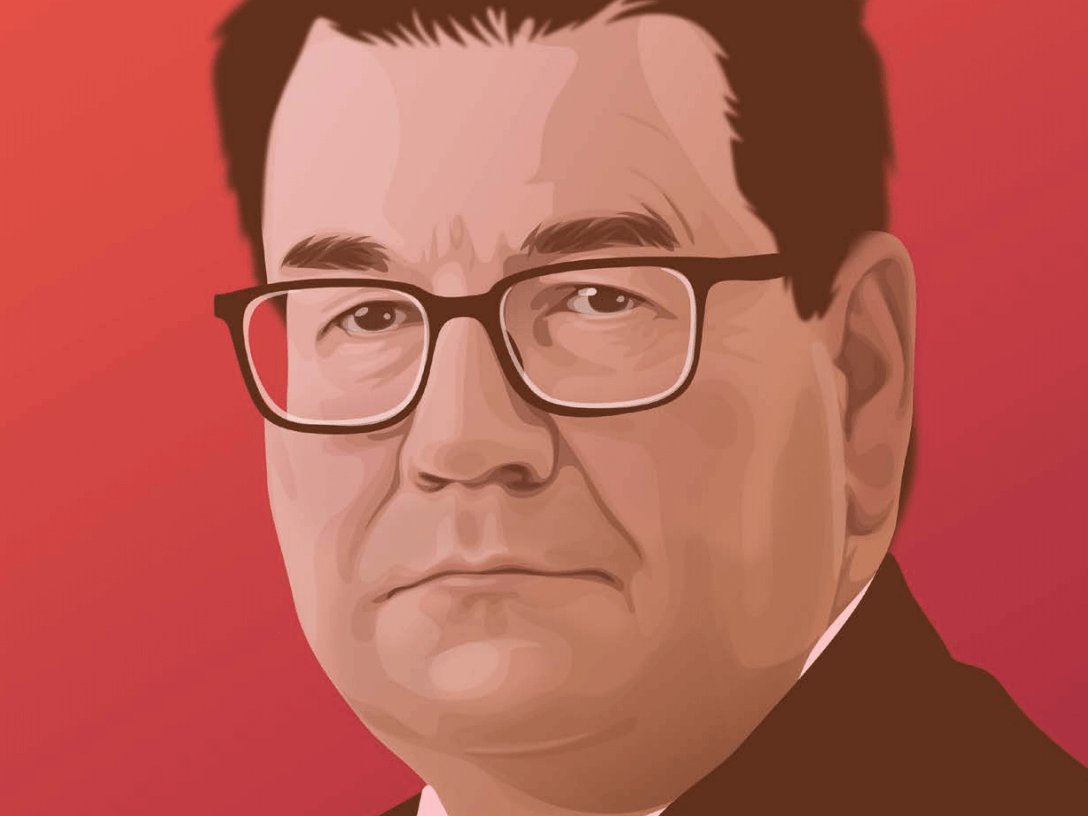

This reluctance to lead on housing means that Robertson, now Finance Minister, is extraordinarily powerful. The levers are, by and large, in his hands. The question is: will he use them?

New Zealand housing is in perpetual crisis. According to CoreLogic, in January this year, investors — that is, people who own multiple properties — snapped up 41% of houses sold that month. Investors make up a record 30% of the housing market; first-home buyers sink to only 22%. “The Kiwi Dream”, a weird Americanism the Labour Party was using last decade to describe the right to home ownership, is apparently just that. A dream. It’s equally grim for renters, too, with Statistics New Zealand finding that in the nine months to March 2020 (so, pre-lockdown), household income increases were almost entirely swallowed whole by increased housing costs.

As a person in his late 20s, I never expect to own a home. Even on my managerial salary, it’s impossible to keep up with runaway rent increases while saving for a 20% deposit. Something has to give. Either you cut every other cost to the bone — transport, food, pleasure in life — or you do the new normal: move in with your parents (or, in my case, the in-laws). It’s not uncommon for housing costs to suck up more than half of a person or couple’s income. Even in formerly “undesirable” locations like Kawerau, house-price rises are out of control. In January, the house-price-to-income multiple was 7.64. That means the median house price is almost eight times the median income. According to research in the US, “affordable housing” constitutes a multiple of 3 or less.

Robertson has perhaps the finest political mind in Labour, and is a genuine social democrat, so he knows all this. Yet, time and again he seems reluctant, like his leader, to act. In November, he threw the housing initiative to the Reserve Bank, writing to governor Adrian Orr seeking advice “on whether to include stability in house prices as a factor for consideration in the remit when formulating monetary policy”. Orr warned against the option, saying there could be adverse trade-o s. But late In February, Robertson pushed ahead regardless, decreeing that the Reserve Bank must consider government policy on house prices when making monetary decisions. This is all well and good, but it’s hardly the ramp-up of housing supply that we need.

Bring back KiwiBuild? In a sense, yes. One thing the government can rightly claim credit for is its public housing programme. We’re building state homes at a rate unseen in decades. Yet, with a growing population — five million, baby! — it’s scarcely enough to keep pace. That throws the initiative back to Robertson. The government’s books are in surprisingly good shape. Debt levels remain low by international standards, so the cost of borrowing remains favourable. New Zealand is in a better position than other countries, or even a better position post-the global financial crisis, to invest big in housing. That could mean bringing KiwiBuild back to life. Or it could mean ramping up those state homes. Whatever option or combination of options is chosen, Robertson has to make a choice.

Either that, or future New Zealanders might look back on this government as a once-in-a-generation opportunity lost.