Sep 13, 2022 Politics

The next election is National’s to lose. Two years of Covid and its hangover have sent 450,000 median voters back across the red/blue line. That 15% swing against Labour suggested by post-Budget polls would be the greatest against a sitting government since George Forbes’ United–Reform coalition was smashed by Michael Joseph Savage in 1935. The closest would be the 13% swings against the shambolic Lange-Palmer-Moore regime in 1990 and after Jim Bolger’s broken promises in 1993.

Jacinda Ardern may lament fickle median voters caring more about the price of cheese than her diplomatic triumphs, but she’ll have that in common with most of her defeated predecessors, including poor old Forbes.

Christopher Luxon is no Savage. There’s no suggestion he’s interested in radical reform. Indications are his would be a government of the palest blue. At most, it would resurrect the Key-English-Joyce era, with those three National patriarchs lying behind the Luxon project.

When John Key manoeuvred into politics in 2001, the worry was his years abroad made him out of touch with contemporary New Zealand. But Key was away for only six years, in his mid-to late 30s. He was working in Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland from 1982 to 1995, the era still providing context for politics in the early 2000s.

More than any of his post-World War II predecessors, Luxon seeks to lead a country he can’t know very well. He was away for 16 years, from 1995, when he was 25, to 2011, when he was 41. That’s closer to permanent emigration than an extended OE. His job on return was running the state-owned airline, also focused offshore.

According to those close to both, this difference shows in Key and Luxon’s respective general knowledge of New Zealand and its politics, economics and policy. Luxon has no intuitive connection to National’s 1999 defeat, the stabilising Helen Clark government, the Don Brash insurrection or Key’s tilt back to the centre. His perspective is limited to the last two Key-English-Joyce terms, followed by Ardern’s outstanding crisis leadership but failed reform agenda. All else is either new, or faint memories from his teenage years and early 20s.

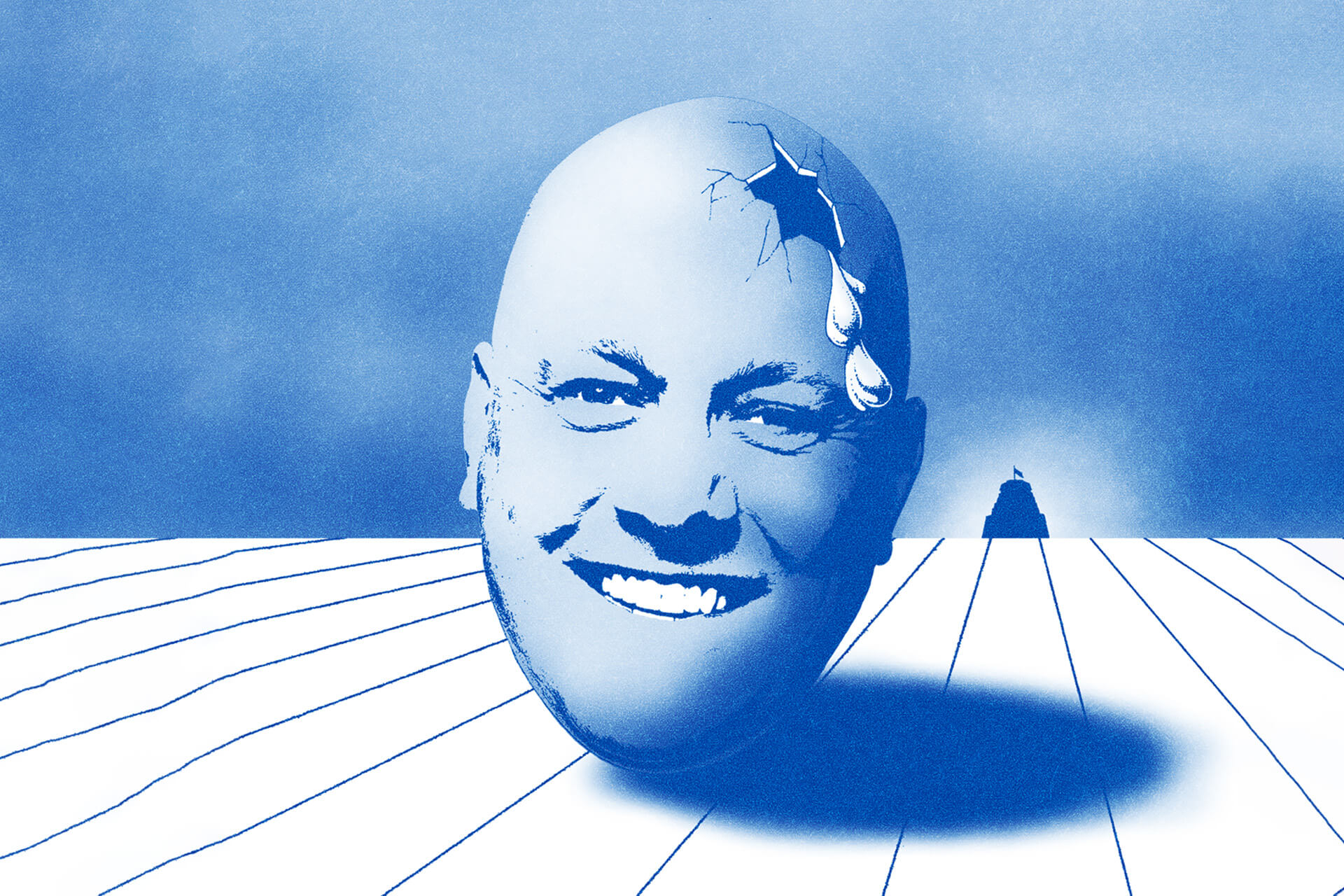

Nicky Hager called Brash the Hollow Man. Yet, of this century’s major party leaders, the former Reserve Bank governor and Ōrewa-speech author was — for better or worse — the most full of ideas and determined to deliver. In contrast, Ardern, Key and even Clark and Bill English seem more interested in holding office than exercising power. Luxon may be the hollowest yet.

National’s liberals, Act supporters and pretty much every Labour and Green voter initially worried about Luxon’s happy-clappy religious beliefs. His maiden speech declared that his faith “has anchored me, given my life purpose and shaped my values”. But, when deciding policy, it turns out faith doesn’t hold a candle to realpolitik.

Luxon believes abortion is murder but, like Catholic farmers English and Bolger, he promises not to raise a finger to stop it. He accepts the results of Act’s 2020 euthanasia referendum. Overall, Luxon’s voting record suggests he’s more liberal than Bolger, English or Simon Bridges, a born-again provincial lawyer.

Too new to Parliament to be put to the test, he insists he would have supported Labour MP Louisa Wall’s Marriage Equality Bill. He voted for Justice Minister Kris Faafoi’s Bill banning conversion therapy.

More conservatively, he lined up with only 14 others to initially vote against Wall’s Bill creating 150-metre safe spaces around abortion clinics. But he changed his mind and voted for it to become law, leaving just nine National and three Labour MPs opposed.

On race, National swung towards Brashism under Judith Collins, but has returned to the Key-English and Bolger-Shipley mainstream under Luxon. National activists enjoy that their party’s record on Treaty settlements is vastly superior to Labour’s, and was first to fund te kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori and wānanga. National’s basic ideology of decentralism also makes it more naturally supportive than Labour of programmes run by iwi and Urban Māori Authorities. The National Urban Māori Authority, Te Whānau o Waipareira Trust and Manukau Urban Māori Authority probably wouldn’t have had to sue a Luxon government to help the Covid vaccine rollout the way they had to Ardern’s.

Similarly, it’s impossible to imagine a Luxon government being worse than the incumbent in respecting Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s right of first refusal. To keep National’s residual Brash wing happy, Luxon will keep promising to scrap the Māori Health Authority and co-governance of Water Services Entities. In office, the changes will involve new logos, websites and stationery.

Ultimately, it won’t be social liberals dismayed by a Luxon government but market ones. Robust economic reform is also off the agenda. The 90-day trial period for all new hires will be back and the new Fair Pay Agreements gone, assuming any are in place before the election. Something like Steven Joyce’s old “Business Growth Agenda” brochures will get published. But privatisations are ruled out.

On climate change, National is as committed to meeting He Pou a Rangi’s emissions budgets as Labour and the Greens, differing only marginally over policies to deliver them. In any event, the budgets won’t be met, whether there’s a Labour-Green or National-Act government.

Treasury forecasts that Labour would raise $391 billion in tax over the term of the next Parliament and spend $403 billion. Any changes to those numbers will be within the margin of error, with global events and economic developments influencing them far more than any policy changes. Even if next year’s Budget includes a big bribe like 2004’s Working for Families — which National slammed as “communism by stealth” — it too will survive a change of government.

So what’s the point? Well, not much, except who you want to see talking from the Podium of Truth each Monday and maybe who would be better at delivering, say, improved mental health services. It’s probably Luxon.

–