Aug 14, 2023 Schools

Natasha*, a teacher at a small, traditionally decile 1 primary school in central Auckland, is exhausted after another busy day in the classroom. This isn’t an unusual feeling for her, but one built up after years of working in a system she describes as showing “systemic dysfunction”.

“I give myself this year to decide if I stay or not. Because as much as I’m dedicated to this profession, I can’t do it if I’m not at my best. You need a certain amount of energy. You need to be able to give a lot. And if you feel like you’ve got nothing left to give, if you’re running on fumes, then you’re not the best educator you can be. It’s a tough decision, but that’s where I’m at.”

Rhys Feeney, an English teacher at a low-decile secondary school in the lower North Island, and a Master of Education graduate from 2019, is at a crossroads too. Of the 25 people Feeney graduated alongside, only 11 are still teaching. Perhaps this should not have come as a surprise. In their first lecture while studying to become a teacher, Feeney was asked to write a crisis management plan to use when — not if — they had a mental breakdown. Later, an experienced teacher came in as a guest lecturer to tell the story of how they became so stressed that they had a heart attack in class.

Feeney admits they don’t know how much longer it’ll be before they join the ranks of non-teaching classmates — or move to Australia. “I’m on the pathway that I think most teachers are on, where you become more jaded as you get ground down by the realities of 55-hour work weeks,” Feeney says. “I was 23 when I started, and I’m 27 now. Essentially, I’ve given up my 20s […] working myself to the bone.”

In Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay, Jacky Braid returned to teaching last year after some time away working at Massey University in professional learning and development. An experienced Japanese, ESOL and digital technology teacher, Braid first taught in Dunedin before moving to the North Island to be closer to her elderly mother.

But after only a year and a half, Braid decided to leave the profession to care full time for her mother. She says that while she would like to “leave the door open” to return to teaching one day, “at the moment I have lost all passion for it. I’m burnt out. I’m feeling like I can’t do this — I can’t maintain it.”

Teachers have been feeling the pressure for some time, consistently citing escalating workloads as a source of stress and anxiety, but the pressure was magnified over the last three years. The impact of Covid-19, both in the switch to remote learning during the lockdown phase, and the impact of staff and student infection in the post-lockdown phase, has been severe. In an Education Review Office survey in 2021, only 32% of teachers agreed that their workload was manageable, down from 42% in 2020. Lockdowns meant drafting entirely new learning plans on tight deadlines, and staff and student illness means teachers are often caught in a perpetual cycle of ‘catching up’. The burden is particularly acute for younger teachers — many of whom are digital leaders within their schools — with only 25% of teachers aged 18–35 agreeing that their workload is manageable. Adam Weir, the head of social science at Wainuiomata High School, says when the pandemic arrived, teaching at a low-decile school went from “not easy to barely scraping through”.

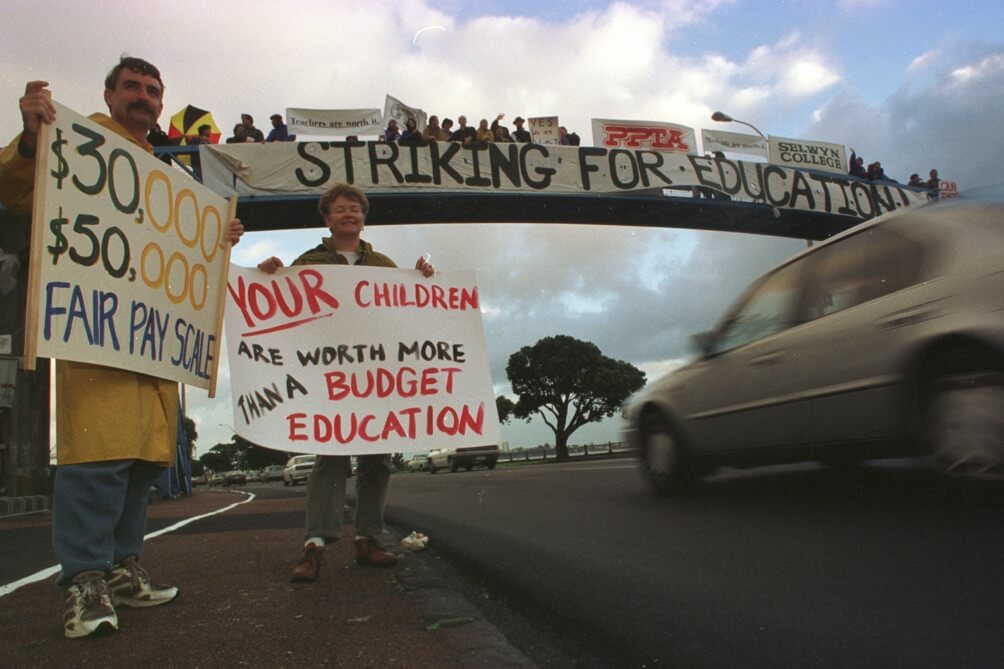

Teachers protesting for better pay and conditions, 4 April 1991. Photograph NZ Herald

That autumn of 2020, Weir was half of the two-person team at Wainuiomata who trained their colleagues in how to switch to remote learning — on top of teaching his own classes and parenting his locked-down children. He was struck, during the first lockdown in March–April 2020, with how well everyone came together to do what needed to be done. But Weir says the Ministry of Education was slow to provide guidance and resources (including masks and air purifiers), leading to a lack of consistency from school to school. On the same day that Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the Level 4 lockdown, Cabinet approved the Ministry of Education’s ‘distance learning package’, which included funding for modems in low-income households. Coverage was patchy, however, with some schools receiving too many and other schools receiving too few.

The continuing impacts of Covid-19 are not limited to administrative challenges or teachers and students entering a cycle of infection and reinfection. “You’ve got us being hammered by Covid, then we’re taking it home to our families,” says Weir. “We have no way to avoid it, because the most the Ministry has given to us are basic surgical masks. Our classrooms are often not fit for purpose to be safe working environments during a pandemic, and schools don’t have the resources to convert dodgy spaces to safe places.”

In an editorial published in the New Zealand Medical Journal in March, a group of high-profile public health researchers headed by Associate Professor Amanda Kvalsvig of the University of Otago noted that “New Zealand school teachers had the highest Covid-19 infection rates of any occupational group”. That finding aligns with international evidence demonstrating that, absent preventive measures, Covid is rapidly transmitted within schools and spreads from schools into homes. In Italy, one of the first countries in the OECD to suffer a devastating outbreak, researchers found that in classrooms with optimal ventilation the risk of viral transmission is 80% lower than in classrooms with poor ventilation. Yet, in New Zealand, support for ventilating classrooms is ad hoc, with the Ministry of Education often recommending opening a window rather than releasing funding to install or upgrade an actual ventilation system.

Moe, a recently graduated English teacher at a low-decile South Auckland secondary school, remembers the first peak of the Omicron wave. Some days their class was down to fewer than half a dozen students. With such variability in attendance due to illness, Moe says it was extremely challenging trying to “teach content in a meaningful way for the kids that were there, without disadvantaging the kids that weren’t, through no fault of their own, because everybody was sick”.

Like Weir, Moe says they wish masks had been mandated in classrooms for longer. It was incredibly difficult to encourage good mask usage after it shifted to being voluntary, they say. “I know colleagues that have had [Covid-19] four times in the last year. When you start to think about the effect that that has on them personally … but also on their students, if they’re constantly getting relievers in, who have no relationship with the students or with the subject matter.”

“If you miss school, it can be incredibly hard to catch up,” they add. “Our kids don’t have access to devices. They don’t have the internet, so they can’t do distance learning.” When students are well again, large class sizes and huge workloads mean that teachers often can’t provide that one-on-one time required to catch students up with their classmates.

Alongside pressures from Covid-19, which are felt by everyone even if they impact on teachers in a specific way, changes to the education system are also being introduced at a pace so rapid that already overworked teachers often don’t have the capacity to plan their implementation.

Teachers told Metro time and time again that the Ministry of Education did not understand the pressure they were facing and would demand that a new curriculum or system be rolled out in an impossible timeframe. In March 2022 the government released one of its landmark reforms — the compulsory addition of New Zealand history to the national curriculum. The curriculum covers the scope of human history in Aotearoa, from AD 1200 to the 21st century, and comes after decades of lobbying and activism. Yet schools were given only a year to plan their implementation, with the expectation that teaching from the curriculum would begin in the first term of 2023. In some respects, that deadline was manageable — parts of the curriculum are highly prescriptive. Yet in other ways the deadline was impossibly tight. Schools must now deliver “local histories” that reflect their place and their relationships to whenua and hapū and iwi. But determining what constitutes local history, many teachers say, is an exercise that must take place in partnership with hapū and iwi across many years — not within a single year that the Ministry of Education sets from on high.

Kahli Oliveira has been teaching for 24 years, and this year moved out of the classroom and into a management role as deputy principal of Konini Primary School in Glen Eden. She says the pace and amount of change is simply too fast and too big. While the changes themselves are seen as a positive thing for education, they are not being introduced in a way that gives teachers the ability to upskill, to plan or to properly implement them. “There’s a lot of that feeling of, ‘We’re not really getting anything less, we’re just having to add more’. There’s just so much, so much.”

Natasha in central Auckland says these Ministry-driven changes are a “frequent worry”. For her the solution is obvious: “I think the changes need to coincide with additional relief time for professional development time for teachers, or a realistic timeline of when we need to roll things out, so it’s not just ‘Snap our fingers, okay, do this now’.”

The need for time away from classroom teaching — which can be used for marking, planning lessons, professional development or one-on-one time for students with additional needs — is a call that came through clearly in recent collective employment agreement bargaining between the two main teachers’ unions and the Ministry of Education.

Relief time is a particularly frustrating issue for part-time teachers who are not entitled to any at all. Jacky Braid reflects back on her first teaching role, which was part time: all her non-classroom activities were expected to be done in her personal time. She explains that this hasn’t changed even in the latest offer from the Ministry of Education. “It’s been completely ignored in this round.”

Part-time teachers choose their work because they have family responsibilities, or other jobs, or perhaps are experienced teachers easing towards retirement, explains Braid. But the lack of relief time is likely to push those people away from teaching, further exacerbating staff shortages and seeing significant experience lost to the system.

The other key issue for teachers’ contract negotiations is pay. At a time of high inflation, teachers are refusing to let their salaries fall further behind, demanding increases that, at the very least, meet the rising cost of living. In the year to March 2023 inflation was running at 6.7%.

Teaching requires a minimum of three years of university study, but most commonly four (a three-year bachelor’s degree followed by a postgraduate diploma in teaching). The gap between educational requirements and pay rates is particularly galling, as Rhys Feeney notes. “To have something like a master’s degree, and to start on $56,000, and then to get to $90,000 — which is, like, starting salary for most places that a master’s degree would take you — after eight years, it’s hard, right?” they say. “If I want to buy a house, I need to quit teaching. Inflation goes up faster than my wages, and now I’m back to eating like a student — just lentils and stuff.”

Natasha agrees, noting that despite being relatively early in her career, she is “not that far from the top [of the salary scale], and that’s really shocking for me. I’m not a beginning teacher but I’m still early in my career, and that says to me, ‘Where is the incentive to stay?’ We’re often told ‘You’re not in it for the pay’ and that’s true, but we’re also not doing it for free — it’s still our career. It’s one that requires a high skill level, qualifications and education, and I don’t think that is reflected in how we are compensated.”

Teachers protesting for better pay and conditions, 23 May 1969. Photograph NZ Herald

The rising cost of living has meant that Natasha now spends everything she earns and can no longer save. But she still sees herself as lucky compared to some of her colleagues, saying she “can’t imagine what it would be like for a beginning teacher who might have children or dependents”.

“I’m incredibly privileged in lots of ways,” says Moe, who rents, at a discounted rate, a house that her father owns. “But I don’t think that I will ever join the housing market in the profession that I’m in — I just don’t see that as possible. My partner and I don’t think we’ll ever have kids, because of the amount of money it takes to support them.”

“It’s hard,” she adds, sadly. “I look at the difference between here and Australia and it’s so stark.” In Queensland, teachers earn $75,000 in their first year. “It’s so hard not to think about the things that could be different [if we moved].”

Together these issues — health and safety, workload pressures and pay — are bread and butter for trade unions. Teaching is one of the most highly unionised professions in Aotearoa. Between them, the New Zealand Educational Institute Te Riu Roa (NZEI), representing early childhood and primary school teachers, and the Post Primary Teachers’ Association (PPTA), representing secondary school teachers, count the vast majority of teachers as members. Under the previous National-led government, the teachers’ unions fought hard against national standard reforms and charter schools, securing an end to both policies in the first term of the incumbent Labour government.

How then, despite strong and active unions and a nominally friendly Labour government, have teachers reached this current crisis?

Stephanie Mills is the national secretary of NZEI. An experienced political campaigner with a background at Greenpeace locally and internationally, Mills worked for NZEI in several roles prior to being appointed national secretary in early 2022. She says NZEI had to walk a tightrope on Covid-19, with members far from united on whether to push for more public health mitigations in schools or not. In fact, they lost members for taking a strong stance in support of mandatory vaccinations. “We were really clear that we didn’t have public health expertise,” Mills says. “The question was, if we strayed from the official advice, where do we land, and how do we justify that?”

“Our ultimate advice,” she continues, “was that your school board, as the employer, has the health and safety responsibility.”

Natasha, an NZEI member, says that despite being disappointed by what she saw as a lack of support for stronger health measures, she felt like her union “supported us as best they knew how. If they had had appropriate public information earlier, I feel like things would have been different.”

“We’re not expecting everybody to have all the answers, and I’m understanding of the fact the pandemic was a new thing for us, but I feel like a lot more could have been done to prevent the worst of the impact which will have a long-lasting impact on so many teachers.”

PPTA member Weir is deeply disappointed by what he sees as union inaction on health and safety. “Honestly, I cannot understand why [PPTA leadership] have not made workplace safety around Covid-19 a critical bargaining position right now,” he says. “This is our war, and we’re not even fighting it.”

“I have peers who are on their third or fourth case of Covid-19. To bring it back to what parents care about, and what society needs, we need well-educated kids. Kids need to be healthy to be educated. Currently, teacher absences, plus student absence, is having a huge impact on progress.”

During the initial Omicron wave in 2022 many teachers exhausted their sick leave entitlements. Under the mandatory seven-day isolation rules, teachers would take up to five days’ sick leave. If a household contact also contracted Covid, it could also mean another period of isolation and another five days of leave. The teacher unions pushed hard for extra sick leave entitlements, but many teachers viewed that push as an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.

In 2017 NZEI launched its ‘Kua tae te wā — It’s time’ campaign, which helped to secure a member-ratified collective agreement in 2019. At the time, NZEI proudly stated that their efforts had “secured a significant pay increase” and “won eight teacher-only days across three years, without the extension of the school year, and a reduction in some of the more burdensome appraisal requirements”.

But without a pay rise since July 2021, and amidst significant inflation, Mills says the Ministry needs to step up with an offer that meets teachers’ needs.

“The government offers have been so slow in coming,” said Mills, “and while there’s been some welcome shifts [the] constant refrain is you either have this or you have that — you can’t expect a decent pay rise and attention to your conditions.”

But are the teacher unions doing enough to push the government into action?

“I do think the impact of the Tomorrow’s Schools model — which is still at heart a model about competition not collaboration, about atomisation not connection — means that it’s really hard to get consensus in the sector or sufficient consensus to move the big things. So that’s why I think change has been slow. Often the Ministry has tried to seek consensus, or we’ve tried to seek it from our own members, and there’s still problems.”

Tomorrow’s Schools is the set of reforms undertaken in the 1980s and 1990s devolving governance for individual schools to local boards of trustees — essentially granting significant autonomy to schools to ‘compete’ for students.

Mills sees the relatively new pay equity settlements as an opportunity to address some of these systemic issues for teachers. “Some unions were happy to settle on just pay,” she notes, “but we’ve always said we want our sector to be a learning sector, so a pay equity settlement for us has to include career development, career pathways, professional learning, and pay attention to the systemic funding settings that created and perpetuate that undervaluation in the first place.”

In the interim, though, NZEI and PPTA members are reaching the end of their tether.

Moe says she and her colleagues are “incredibly skilled, passionate people” who are just “really fucking tired, and really sick of being told nothing from the negotiations. But then we’re constantly being updated with all the new things the Ministry wants us to do … Really, who do you think is going to implement them?”

The Ministry, she says, thinks “we don’t have any power, and they don’t need to listen. They assume that if they drag it out for long enough, we’ll just give up, and we’ll come to some sort of agreement like we always do. But it seems bizarre that, in an election year, they want to keep stalling this battle with really high stakes for the future of this place and the future of our young people.”

* Some names have been changed to protect individuals.

–

This story was published in Metro N°439.

Available here.