Dec 2, 2024 Society

It’s nearing 3pm on a sunny Thursday, yet Mark Eltom can’t tell what time it is. Here, in a Parnell basement bathed in blaring fluorescent lights, it is whiskey time all of the time. “I do a heavy pour,” Eltom warns. He passes me a glass and says, “That is going to be fucking strong.”

The Canadian-born New Zealander works in the bottom of a converted 1950s woolshed surrounded by stainless-steel equipment and caramel-coloured spirits. He speaks a little like Willy Wonka — if the king of chocolate embraced whiskey instead of sugar. He sniffs, raises his glass and says, “Let’s have a little chitter-chatter.”

When Covid hit, Eltom was at home in Ōrākei spending far too much time in his garage. Bored, he ordered a liquor still from China. He thought: I’m going to make whatever this still makes: gin, whiskey… He didn’t tell his partner.

When it arrived, Eltom got to work. Despite his background in viticulture, he was terrible at it. “I’m the world’s shittest fermenter,” he says. “I hate that part.” Instead, he began thinking about the key ingredient that makes most spirits taste good: time. “They age [spirits] in oak barrels,” he says. “It can take [anywhere from] a few years to multiple decades to get the spirit right.”

Many have tried to refine the alcohol-ageing process — a delicate, risky, expensive and time-consuming gamble that can render entire warehouses of stock worthless if it goes wrong. “Who the fuck knows if in 10 years someone will want to buy something?” says Eltom. But so far, no one’s found a better way.

Eltom was undeterred. He wondered: “What the fuck does nature do over this time? Can we speed this up?” He began tinkering, settled on a process, ordered more equipment, then built a prototype, the first ‘Reactor’, to realise his vision. Because of pending patents, all he can say about this is: “Our technology takes 10 years down to a few days.”

His first batch of spirits in the Reactor took nine months. His second was much quicker. Eltom kept refining. He ordered more equipment, made bigger batches, and bootlegged the results to friends and family. Their feedback — including, “How the fuck did you do this?” — kept him going, even when his garage caught on fire.

Photos from this time show Eltom in his garage, wearing gumboots, standing in mud, surrounded by his DIY set-up, an assortment of wires, boxes, barrels and tubs. He’s drinking whiskey out of an old jam jar. He looks happy. This, Eltom says now, was the fun part. “I thought, ‘Right, fuck it. Let’s go for it’,” he says.

—

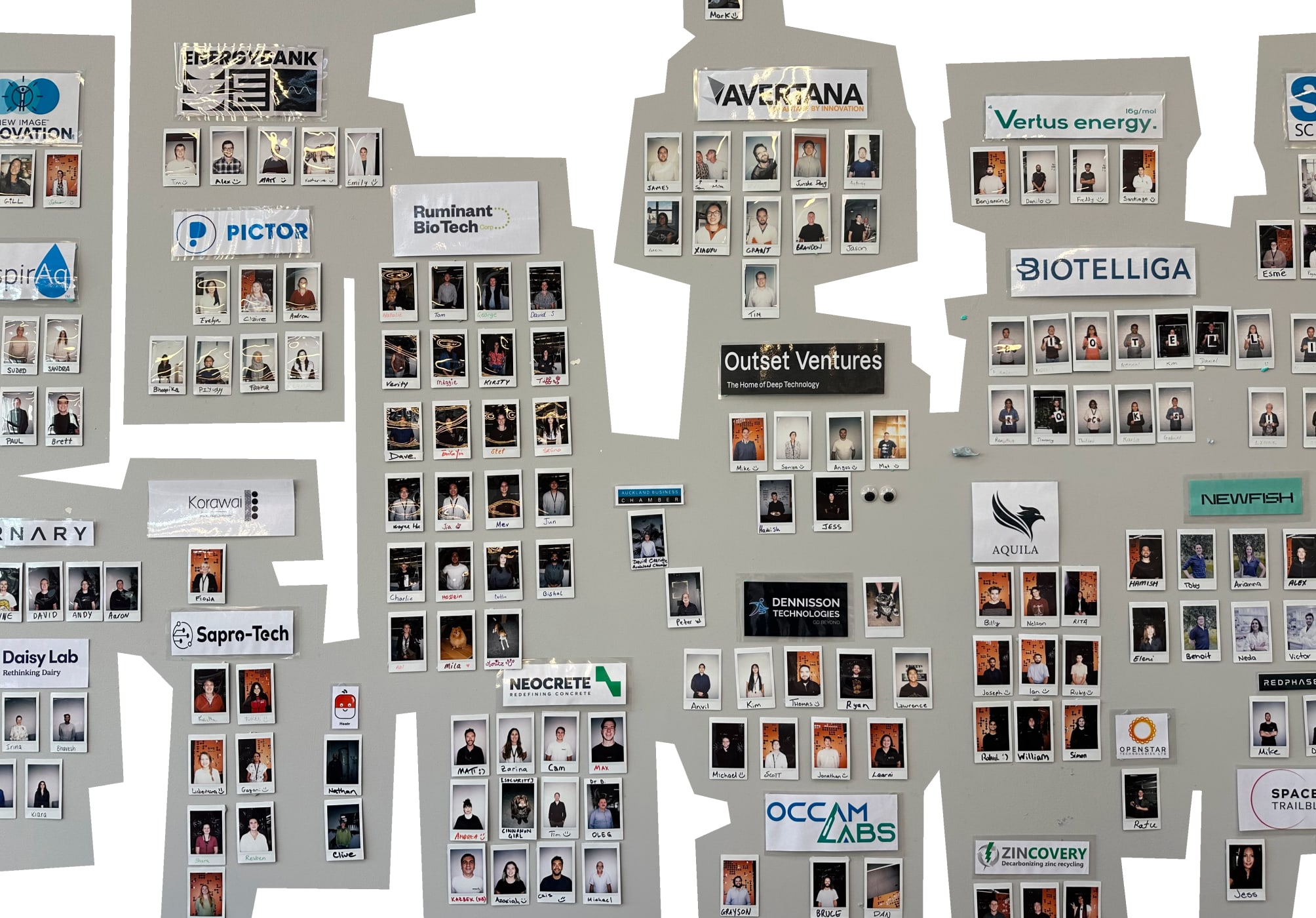

If Eltom was going to take this seriously, he knew he needed new premises. He found Outset Ventures, a deep-tech incubator based in Tāmaki Makaurau since 2006, where his spirits company, Reactory, is surrounded by more than 20 like-minded business propositions with optimistic founders just like him.

With pinball machines in the hall and Brothers Beer on tap in the kitchen, the Balfour Rd location has the vibe of a WeWork set in the minimalist world of the TV show Severance, a fictional office space where staff are so dedicated they have their brain ‘severed’ so they can’t take work secrets home.

Above Eltom are four floors full of hopes, dreams, determination and fluctuating income streams. “This isn’t a start-up in the sense of a software company where you’ve got to populate a company with a whole bunch of programmers and pizza,” explains Sean Simpson, an investment committee member and adviser who co-founded the clean-tech company LanzaTech in Outset Ventures’ early days.

No one is short on enthusiasm. With some, the zeal borders on manic, a touch unhinged. That’s because these founders are here, day in, day out, working on single-minded visions that attempt the impossible: forcing change, disrupting industries, charting a new future. It’s Silicon Valley made with No. 8 fencing wire.

One wants to make dairy products without cows. Another is trying to replace hospital equipment relied on for more than 100 years. A third has found a use for the waste created by the steel industry. I’m shown a room where clothing is being developed to improve athletic abilities.

All these people are working on a global scale. All have climate change on their minds. Some have been at it for years; others, more than a decade. All believe their ideas will fly. Yet, for most, profitability is still light years away. They rely on investors and fundraising to stay afloat. Any of these companies could go under at any moment, and it might not be anyone’s fault. “These aren’t people who’ve made terrible mistakes,” says Simpson about founders who fail. Instead, they could be stymied by something small or unexpected. The landscape is incredibly fickle. “Sometimes the timing’s just off.”

—

At the end of every month, Outset Ventures hosts an event. Every founder is invited. “We celebrate things that are going well… and we farewell people,” says Mat Rowe, Outset Ventures’ enthusiastic co-founder and CEO. “You’ve got to treat people with respect on the way up, and on the way down.”

When it works, it really works. For inspiration, anyone who rents a space here can take the elevator down to Eltom’s basement to see a piece of shrapnel embedded in the wall. Someone has framed it and hung a ‘Danger’ sign nearby — a warning worth heeding.

It’s from an explosion caused by Peter Beck’s Rocket Lab, a real-life moonshot that began here in 2006 and has since launched 51 rockets into space (almost all of them successfully). Now, Beck’s company is valued at US$2.4 billion, is attempting to go to Mars, and is the focus of the recent HBO documentary Wild Wild Space.

Simpson’s LanzaTech, which uses bacteria to turn carbon waste into ethanol, began around the same time as nothing more than a PowerPoint presentation. Now, it has four plants in China and recently launched a subsidiary company called LanzaJet, creating sustainable jet fuel.

Bill Gates and Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund back the company. But, nearly 20 years on, LanzaTech is still riding the start-up roller-coaster: the Wall Street Journal recently reported that it “isn’t making any money, is falling short of its earnings predictions and its stock has crashed”.

For Eltom, the ride is moving more quickly than most. Under the label Eltom Distillery, his quick-aged spirits are already being sold in bars around Auckland and through his website, and can be purchased duty free at the airport. He’s thinking bigger, believing his breakthrough technology could be used to make perfumes, cologne — “anything that’s aged in a barrel”.

The potential market? “It’s global,” says Eltom, who touts his company’s clean, green credentials. He’s come a long way, but the real work is just beginning. That means travelling, convincing people that his new technology works better than traditional methods, finding new investors and keeping a constant eye on quality control. It’s all-consuming.

To kick on, many things need to align. Will Eltom succeed? Will other businesses at Outset Ventures realise their dreams? Perhaps the answer can be found on a bottle of spirits — a 57%-proof whiskey with notes of “vanilla sponge cake and smooth candied apple” — sitting on a table outside Eltom’s door.

On it is a piece of tape that contains two handwritten words: “Fuck knows.”

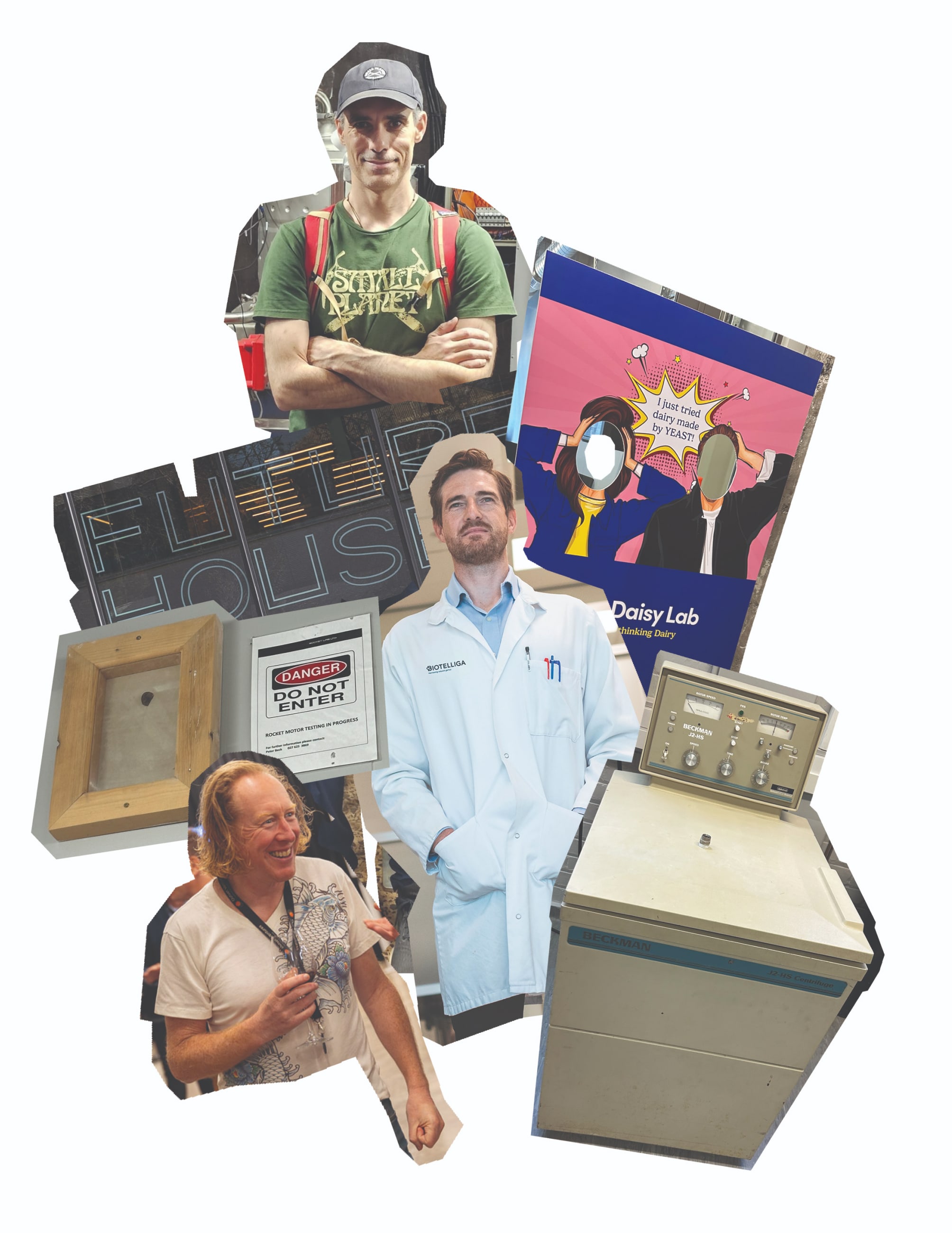

“We’ve got our old relics,” says Emily McIsaac. She points at the lab equipment around her, a collection of wonky machinery connected through an intricate web of piping. Some of it is duct-taped together. Her voice is nearly drowned out by the hum. “These are second-hand from the United States,” she says. “These we have on indefinite loan from Auckland University. This one’s a demo model.”

As she talks, a milky-white liquid bubbles away in a vessel nearby, cementing the vibe of Beaker and Bunsen’s mad scientist lab from The Muppets. A museum-ready centrifuge sitting in the corner does little to dispel this impression. “We pulled that up from downstairs,” says McIsaac. “We use it.” Her start-up is clearly operating on a budget. “We’re very thrifty.”

This is the epicentre of Daisy Lab, a team of six who spend their days in a lab a floor higher than Eltom’s with a permanent view of a grey brick wall. It’s still early days. In 2021, McIsaac was a university student who joined Daisy Lab’s other co-founders Irina Miller and Dr Nikki Freed to research “precision fermentation”. That’s a fancy way to describe their real mission: to make milk without cows.

Their efforts are bubbling away beside McIsaac. “We use genetically modified organisms to produce dairy-identical proteins found in cow’s milk,” she says. They’ve already used the process to make ice cream and cheese. Could I drink what’s in that vessel? “I wouldn’t recommend it,” she says. “We’re in a lab. You’re not allowed to.”

The trio are working on this because, they say, it needs to be done. Dairy is Aotearoa’s biggest export, and the country’s abundance of cows contributes heavily to our greenhouse gas emissions. “The environmental impacts… are catastrophic for New Zealand,” says McIsaac. “The population’s growing. We need more protein. There’s got to be a way to do it more efficiently.”

Daisy Lab isn’t trying to offer an alternative. It doesn’t want to work alongside the dairy industry — its aim is to replace it. In theory, Daisy Lab’s products could help lose the cows which cause all that methane, yet use the factories and equipment already in place to make their version of milk. “We’re helping the dairy industry transition to a new method of protein production,” says McIsaac.

But here’s the balancing act: to make it happen, Daisy Lab needs to bring in money and investors so they can keep researching, keep growing and keep refining their processes. Charting a new future is expensive, especially when you don’t yet have a product to sell. A round of fundraising is under way, and the company’s founders are hoping it will give them enough to build a pilot plant within the next two years — and possibly afford them some new equipment.

“That’s slag,” says Michael Oliver. He slides a jar containing what appears to be metal knucklebones across a boardroom table. It’s the waste product created by the steel industry, tonnes of which pile up around the world as large-scale industrialisation continues apace. Mostly, slag gets thrown away. “China has 20 million tonnes a year thrown on the ground,” he says. “They’re actually starting to build condominiums on it.”

At the other end of the scale from Daisy Lab sits Avertana. Over the past decade, Oliver, the company’s CEO, and co-founder and commercial vice-president James Obern have been developing alternative uses for slag. “We refine [it] into raw material to be used in everyday products, and we leave nothing behind,” says Obern. The transformed products include calcium silica, used to make concrete stronger, and titanium dioxide, the chemical used to whiten things. “That’s the money-maker,” says Obern. Adds Oliver: “It’s all coming out of dirty rocks.”

Soon, I have multiple jars and vials of the different products they can manufacture sliding across the table and piling up in front of me. My head spins with scientific terms and numbers. Obern clutches his coffee cup with both hands. The pair fizz; a nervous excitement spills out of them. That’s because, after 10 years, they’re finally making inroads. A demo plant has been built in Wiri. A contract has been signed in China. Things are moving. The signs are good.

Still, even after all this time, there are constant problems. “You go through ups and downs like a yoyo,” says Oliver. “We’ve had very hard times… You go, ‘Are we done? Are we going to solve it in time?’” Where did the belief come from? I ask. “In the beginning,” says Obern, who spent four years working for Simpson’s LanzaTech before co-founding Avertana, “it was a smidgen of white powder at the bottom of a test tube.”

The pair are confident in their product, and believe the steel industry is ready to wake up to better ways. “China’s said to steel mills, ‘You must use your steel slag, make better use of it.’ Our technology unlocks that,” says Oliver. Avertana doesn’t want to build and own plants; instead, its leadership team wants to license the technology to companies willing to listen. “This is a way to achieve returns they can’t achieve through their main business,” says Obern.

The Avertana roller-coaster ride is typical of the ups and downs experienced by other start-ups at Outset Ventures. “We don’t jump up and down [about it] because we’d be in a lunatic asylum,” says Oliver. But they do exactly that: by my count, the pair leave their chairs at least three times each during our 15-minute chat. They pace, grab more jars and vials, and swing their hands around to demonstrate things. At one point, they offer to drive me to Wiri to tour the demo plant. Later, Obern chases me down in the hall to catch up again, to thank me for listening. He’s still holding his coffee cup.

—

Damien Fleetwood pushes open a squeaky door. Inside, the lights are off and the darkened room smells musty, tangy, a little sweet. On the floor, machines whir, spinning flasks of murky liquid so they’re in constant motion. Shelves bulge with large, flat-packed plastic bags. “This,” he declares, “is solid-state fermentation.”

The bags glow the colour of a decent tikka masala. But it’s not an Indian curry growing inside — it’s fungi, a product that could make chief executive Fleetwood and his company Biotelliga a lot of money. Across the hallway from Eltom’s whiskey lab, a team of 25 attempts a huge job: ridding the world’s food crops of chemical-based pesticides and herbicides.

Biotelliga was founded in 2009, but Fleetwood joined in 2014 as chief scientist and he’s been focused on the company’s lofty aims, and only them, ever since. It’s a mammoth task. “The vast majority of the food around the world comes from large-scale agriculture,” he says. That means anyone who eats corn, wheat or rice as part of their regular diet is also ingesting chemicals. “Don’t ask me about soy,” says Fleetwood. “It’s soaked in it.”

The benefits of creating a cheaper, natural alternative to chemical sprays could improve the lives of every single person on the planet. To do this, Fleetwood and his team take microscopic fungi from the leaves of plants, then grow them into a natural pesticide that can be used on crops at scale. The environmental benefits could be massive. “The chemicals we’re putting on to the food we eat [last for decades],” says Fleetwood. “They go everywhere. We want to change that.”

With a pristine lab coat, dry sense of humour and glint in his eye, Fleetwood could be a scientist from a big-budget TV series. But he quickly gets serious. To enter his lab, I’m asked to wear a white coat and sign a waiver. “We work with hazards, chemicals and potentially hazardous micro-organisms,” he recites from the company’s mandatory code of conduct. “Please don’t touch anything.”

Biotelliga’s set-up is huge, with five labs including a “plant room” and “insect room”, making theirs the biggest premises I see on today’s visit. After 15 years, and having grown to a team of 25, Biotelliga’s finally preparing for launch. Two products await regulatory approval, and Fleetwood believes they’ll be on sale to American farmers by 2028. “If that seems far away, it still seems horrifyingly close to me,” he says.

Even now, on the cusp of changing an entire industry, Biotelliga is a huge risk. Legislation could change, regulations could morph, competitors could emerge, and suddenly Biotelliga could be in trouble. All that work for nothing. “That’s part of being a start-up,” Fleetwood says. “You’re taking a risk, [but] you’re mitigating that risk as much as you can.”

Ask Fleetwood if he’s a gambler and he shakes his head. You would never find him sitting at a slot machine. Yet, here in Outset Ventures’ basement, Fleetwood has turned up every day for the past decade to put everything he’s got on red. Tell him this and he repeats a company line, a version of which could have come from any of the founders I’ve talked to today: “I truly think that our products will be among the leaders, [showing] growers they can replace chemicals.”

Fleetwood realises that while he’s trying to eliminate the pests that destroy crops, there’s one thing he can’t get rid of — if he could, he’d sleep a little easier at night. “The failure risk… is always there”, just like the aphids that keep eating farmers’ crops. “You can never eliminate it.”

As I’m leaving, Fleetwood advises me to wash my hands. After several hours inside Outset Ventures, I exit the doors and squint in the sunlight. A few steps away on the footpath, a delivery driver has stopped his scooter. He consults Google Maps on his phone for directions. He isn’t wearing a helmet. I can’t think of a more fitting analogy for all that’s happening just a few metres away.