Apr 23, 2023 Politics

Labour’s extraordinary incompetence and the biggest fall in real wages since comparable data has been collected mean National-Act should be miles ahead, but they’re neck and neck with LabourGreen-Te Pāti Māori in all the latest polls. Labour’s pollsters, Talbot Mills, have both blocs on 60 seats each. Unless a smaller party defected, there’d be a second election before Christmas 2023.

Every election is ultimately decided by the median voter. When it’s close, they have total power — in this case, not to choose what shade of purple they prefer, but which extreme worries them less.

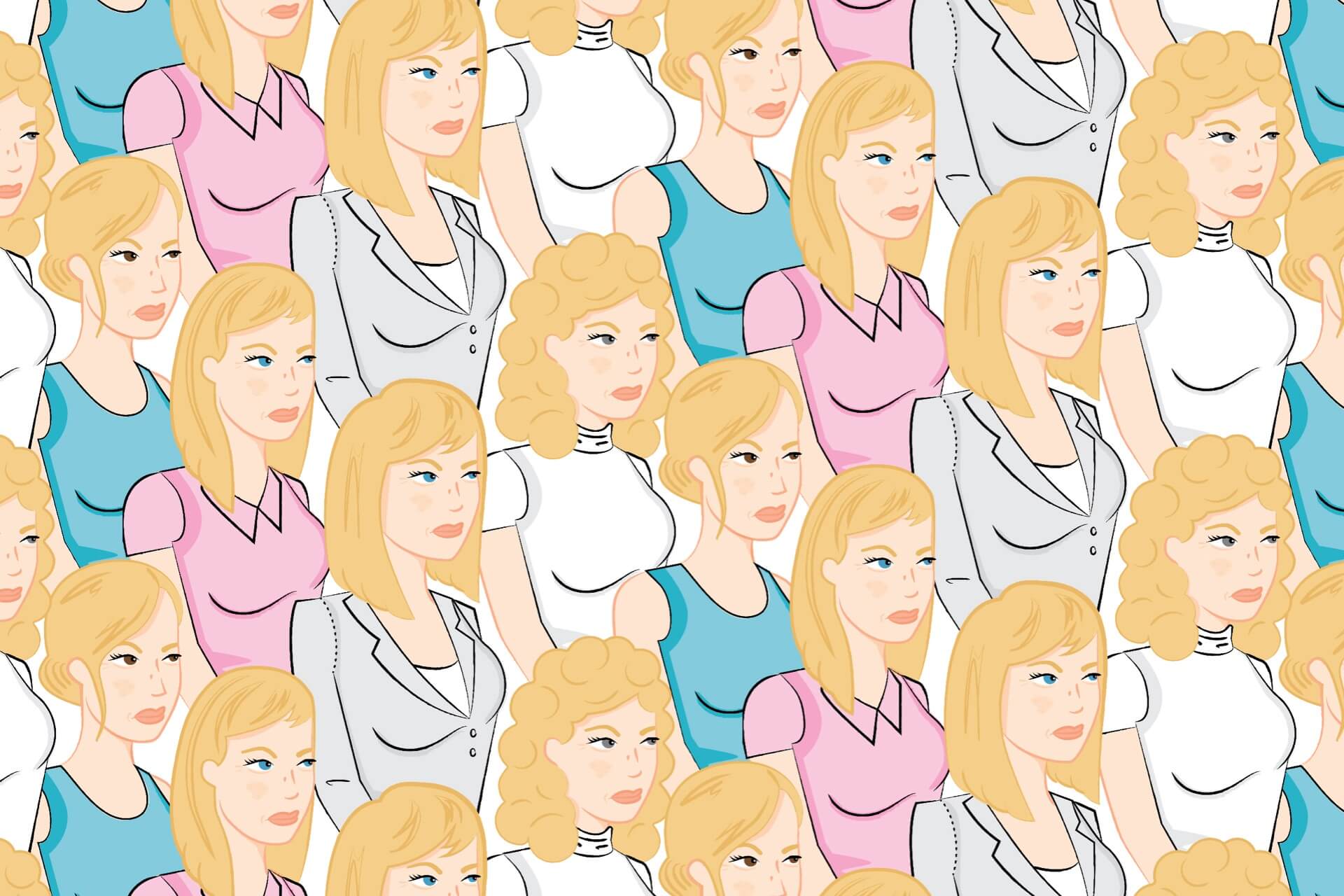

The Kiwi median voter was born in 1984 and is now 38. That person could be male or female, but political strategists assume the latter since women are more politically promiscuous. Her name is probably Sarah, the most popular girl’s name in 1984. She identifies as a Pākehā heterosexual cis-woman, although may not know what ‘cis’ means. If she took any notice of politics as a 15-year-old in 1999, she was enthused by Helen Clark. National had been in power since forever and it was time for something new.

In 2002, Sarah cast her first vote for Labour. While tempted by Don Brash in 2005, she decided he was too much of a risk because of that Exclusive Brethren thing. Also, Clark had delivered interest-free student loans.

In 2008, now 24 and working, Sarah switched to John Key. She stayed loyal in 2011 and again in 2014. That was the year she married Michael, who has the most common boy’s name of 1983 and 1984. Two children followed, Oliver in 2015 and Charlotte in 2017. All four grandparents were still alive to help. Charlotte has recently joined Oliver at the local decile-six primary school. We’ll call it Matipō Road School in Te Atatū. The median voter is usually assumed to be a West Aucklander.

Sarah found the election in 2017 more difficult than her earlier votes for Clark and Key, but ultimately stuck with Bill English. Of the 561 others who voted at the Matipō Road School booth, nearly 40% did the same.

Winston Peters’ making Jacinda Ardern prime minister didn’t seem quite right. While Sarah liked her, especially when Neve came along and after the Christchurch masjidain attack, she saw National as the safer pair of hands and the party was on track to win her vote a fifth time. That changed with Covid, especially after Simon Bridges attacked Ardern’s response and the various leadership shambles that followed. In 2020, she was among the 51% of voters at Matipō Road who enthusiastically backed Ardern’s historic majority.

Now, she just doesn’t know.

Sarah became disillusioned with Ardern during the long Auckland lockdown in 2021. She had a younger sister overseas who couldn’t get home when their father became sick. Yet Covid was good for Sarah and Michael financially. Their employers got the wage subsidy. Things were still tight in the first year of Covid but this year their earnings have recovered.

As the median 38-year-old Auckland woman, Sarah earns $66,000 in 2022, up 20% over 2021, well ahead of inflation. As the median 39-year-old Auckland man, Michael earns more, $83,000 this year, up 11.5% over 2021, also more than inflation. Labour’s student loan policies — and Key keeping them — meant they paid off their student loans in just eight years, before they turned 30, while also saving for a house. It’s the best thing they ever did.

Sarah and Michael bought a three-bedroom house in 2014 for $620,000, with a $558,000 mortgage. It touched $1.2 million during Covid — though it’s probably dropped back to $1.1 million — and the mortgage is down to $500,000. They’ve turned their $62,000 deposit into $600,000 equity in just eight years. All tax-free. Plus they locked in the remaining half million for five years at 3.49%. Don’t tell the neighbours who are still renting, but a bit more inflation might be quite good for Sarah and Michael, as long as the pay rises stay one step ahead.

And yet, Sarah worries it’s not quite real. She knows a budget deficit when she sees one and knows Grant Robertson borrowed $62 billion during Covid. Someone will have to pay it back. She worries that will be her and Michael, or Oliver and Charlotte if it’s passed to them the way the Baby Boomers left their debts to Gen X.

It’s not clear where the money all went. The roads are still a mess and the new $30 billion airport tram, if it ever happens, won’t help West Aucklanders. Matipō Road School is excellent but needs more teacher aides. The hospitals are okay, but haven’t gotten any better for all the money. They risk being overloaded but the government won’t let more nurses in. It was impossible for Michael’s brother to get any mental health support when he flipped out last year after Covid killed his business. Crime is a worry, too. While Ardern and Robertson definitely care, they seem out of their depth. Rumours they’ll write off student loan debt as an election bribe next year might help some, but that doesn’t seem very fair, after Sarah and Michael worked hard in their 20s to pay theirs off.

But all National offers is tax cuts.

They’re not a bad idea, but should be for people earning $66,000 to $83,000 a year, not mostly for those on over $180,000. Key was a multimillionaire but seemed a bit like us. Luxon doesn’t. He owns seven houses, lives in Remuera and went to a weird church. When Sarah had a pregnancy scare in her early 20s, she wouldn’t have wanted to be called a murderer had she chosen an abortion. And then there’s that bully National put up in Tauranga. It turns out he went to King’s College. Key went to Burnside High. Labour may be useless, but Sarah and Michael worry National is always worse for health and education — which, now they’re approaching 40, they increasingly fret about for both their parents and kids.

Most importantly, there’s still Act, the Greens and Te Pāti Māori to worry about. Which is worst? Who would best keep them under control?

Sarah doesn’t know what to do. She also doesn’t know that where she goes, goes New Zealand.

–