Nov 28, 2023 Society

On New Year’s Eve in 1959, aged 19, I saw in the new decade in the back of a police car, vomiting profusely. I had drunk too much snuck-in sherry at the New Year’s carnival at Western Springs and, while riding the Ferris wheel, had emptied the contents of my stomach on my fellow ride-goers.

I slept it off in the Ponsonby drunk tank and emerged into the bright sunlight of 1960 knowing that this would be my time, my place, my era. I knew something good would come to me, but only if I made it happen. What I didn’t know was that the 60s would be the beginning of a slow release of the shackles, the lifting of the horrendous Soviet-style restrictions, censorship and repressions that had followed the Second World War. As the decade dawned, Auckland was a hellhole of racial tension, restrictive liquor laws, cultural and sexual repression. Aucklanders still felt the traumas of the war, and desperately wanted to be connected to a different kind of world. A world we saw in films and magazines. We wanted a part of this world, so we decided to create it ourselves. Auckland City streets plunged into darkness at midnight, due to the power restrictions of the time, which gave us a unique opportunity to own the night.

By 1962, I had sobered up and started a small advertising agency with a couple of friends in an old building on Queen St. I had moved from The New Zealand Herald, where I had worked in its flagship building on the advertising counter, and decided that I could make a go of things on my own. Within a month or so, I had picked up a few fashion accounts, and they were my gateway to parties and nightlife. As a young guy on the scene, I wanted to make the most of it — I discovered an exciting dark world like New Zealand had never seen before. There, I met characters who had a personality-full craziness and a glorious sense of place.

As a teenager, I had worked washing dishes at the Hi Diddle Griddle, est. 1953, situated at the Ponsonby end of Karangahape Rd and often described as the first nightclub and cafe in Auckland. The proprietor was the legendary Jim Jennings, a naturalised American who had roamed the Pacific as a beachcomber and mercenary for hire. The walls were decorated with glorious Tahitian and Hawaiian jungle scenes featuring exotic couples, by the brilliant young mural artist Kristin Zambucka. The Hi Diddle Griddle broke all the moulds of the time, opening the door to a new form of stylish dining. It was the only place open until 4am, and the only restaurant in the country to serve the exotic dish chicken-in-a-basket. Licensing laws in the 50s and 60s were ultra-restrictive, but a blind eye was turned at the Hi Diddle if you discreetly smuggled in a bottle of wine. They had booths, and even a fountain out the back, and a small stage where the dazzling local singer Mavis Rivers (whom Sinatra once called a phenomenon) sang on Saturday nights. Nat King Cole would breeze in when he was in town.

Another notorious eating joint was The White Lady, which was pulled into place at the bottom of Shortland St. This was the largest and probably the best-known pie cart in the country. Open every night, it sold delicious pies, steak and kidney, curried sausages, peas and mashed potatoes. It was a place you went after a party or a dance at the Peter Pan Cabaret or the Orange Ballroom on Newton Rd. The White Lady had a great line-up of mixed clientele — Vivien Leigh from Gone with the Wind and her husband Laurence Olivier dined there once, as did the famous ballerina Margot Fonteyn. It was standing room only — well, it had to be, there were no tables.

In 2014, just a few months before she died, I talked to my old friend Anna Hoffman about those days. She reminded me about the Chinatown at the bottom of Greys Ave, which in the 60s was a neighbourhood full of unpainted weatherboard buildings, dodgy alleyways, warehouses, old shops, and gambling and opium dens. There were two or three wild places in particular, Hoffman and I remembered. This was nightlife on the seedy side.

The neighbourhood was glued together with old Chinese miners who had come up from the goldfields and their families, who mainly originated from Canton (now Guangzhou). Many were highly respected — Wah Jang, the Doos, Mings, Fongs and Wah Lees. The Wah Lee brothers were great musicians who played ragtime on trumpets and guitar and saxophone at the Peter Pan. At the back of most Chinese-run shops in the 60s, games of mahjong or fan-tan were held. A lot of opium was smoked, quite peacefully — it was smuggled in from visiting ships. The two dens I remember well were in Greys Ave and in Airedale St. The cops often raided the Airedale St den, and, by 1965, both dens had become seriously good brothels.

Anna Hoffman was an extraordinary woman. She claimed she had been present at the infamous machine-gun murders at 115 Bassett Rd, Remuera, in December 1963, when Fred Walker and Kevin Speight were gunned down in a bedroom. Both Walker and Speight had been sly-grogging and had also used the house as a gambling den. The murder weapon was a .45-calibre machine-gun, a seriously drastic, Chicago-style killing device. Hoffman said she had been asleep in another room after screwing a sailor, when she woke to gunfire and ran out the back door with her lover. Police arrested Ron Jorgensen and John Gillies three weeks later and they were sentenced to life imprisonment.

It was around that time I got to know Hoffman. She seemed to know everyone in town. On Friday nights, she would cause a sensation by turning up with one of her many boyfriends at the Queen’s Ferry Hotel on Vulcan Lane just before closing time. Young horny office workers would gather there just to see this gloriously beautiful blonde glide into the back bar. The hotel would then close, as all pubs had to, at 6pm — but special clientele were allowed special privileges. Barry Crump was often at the Queen’s Ferry; the writer, drinker and ex-con John Yelash, too; and poet James K Baxter (always barefoot), if he was in town.

Hoffman resembled the glamour star of the time, Swedish actress Anita Ekberg, and I seemed to bump into her at every late-night party. As well as being stylish, she was a talented violinist, and was great friends with Billy Farnell, a brilliant jazz pianist who would move around town often playing up to five gigs each night.

In the early 60s, coffee bars seemed to pop up like mushrooms on Queen Street. Somervell’s next to the Plaza Cinema claimed to be the first milk bar in New Zealand to serve percolated coffee. It was the central hangout for Auckland’s writers and artists — the place to be if you were in the art scene. On Friday nights, you’d find Frank Sargeson, Maurice Shadbolt, Theo Schoon and Michael Illingworth all there holding court. Somervell’s had also been the scene of a brutal murder, in 1955, when Freddie Foster, a disgruntled boyfriend, shot his lover Sharon Skiffington in the head with a shotgun. Hoffman, who was present for that shooting, too (or so the story goes), remembered the shattering of mirrors and glass, the smell of gunpowder and of course the blood. She told me the killing stayed with her all her life. Foster was executed.

Hoffman was known as the white witch of Auckland, and made headlines in The Truth and the Sunday News. She seemed to pop up regularly with outrageous claims and confessions. One time, having returned from a sojourn in Australia where she’d fallen under the spell of a notorious Satan worshipper, she decided to throw her own satanic rights party in the Symonds Street Cemetery. She said it didn’t take her long to get together a group of like-minded women from Auckland’s art scene to join her in midnight rituals — which included dancing naked through the graveyard with a herd of goats she and Farnell milked in Grafton Gully. God knows where these midnight rituals were heading but they made The Truth front page and Auckland City Council stationed security guards at the cemetery. No arrests were made and no goats harmed, but by 1965, Hoffman had given up her midnight rituals and moved on to dressmaking. She later helped to make the costumes for the 1983 film Utu and was still attending parties in Auckland until not long before her death in 2014.

If you weren’t on the last bus home at 10pm, you would move to Embers on Chancery St. Embers always had a great line-up of musicians. The resident band was the Claude Papesch Trio, with Bruno Lawrence on drums and a brilliant bass guitarist, Tim Piper. I thought Embers was the best nightclub in Auckland. It had a small dance floor and a courtyard out back, where there was always someone playing flamenco guitar. Further uptown on Friday and Saturday nights was the Montemartre, tucked into the back of the St James Theatre up a risky set of stairs. It was probably the most sophisticated nightspot in town — smoke-filled, decorated with huge Toulouse-Lautrec reproductions and red lanterns, a hub for the fashionable. Resident band the Dallas Four played outrageously good cover versions of the new hits they’d learned from imported 45s. American jazz pianist Dave Brubeck did a set after his Town Hall concert. It closed at 5am, if ever.

The constant constraint of partying in the 1960s was the 6pm closing. Licensing laws turned us all into criminals, and many pubs illegally sold liquor out the back door, usually under the watchful eyes of the cops. To get your hands on the illicit booze, you had to know the codes. Gleeson’s at the bottom of Hobson St was four knocks; The Star on K Rd was a complicated two and three knocks; and the Astor Hotel on Symonds St was a mere two knocks. The proprietors accepted cash only, in return for handing over a crate or two.

The new restaurants that were starting to crop up were not permitted to sell liquor, but you could smuggle the odd bottle in under your girlfriend’s dress — in those days, the police seemed to search only men. So, having the odd bottle under the table was common, but at 9pm the rules were strictly enforced and all glasses removed. Penalties were severe: serving alcohol to anyone under 21 years of age could incur hefty fines, a loss of licence or two years in the slammer.

Out West on the weekends, three remarkably good restaurants dodged the harsh liquor laws, as the police couldn’t be bothered driving that far to check up. These places were known as roadhouses and the food and bands there were always good. Back o’ the Moon, Pinesong and the Town and Country Roadhouse, run by the wonderful Marge Harré, were all welcoming and warm, more relaxed than central Auckland. And no one gave a damn about drinking and driving, so many cars went into ditches and the foliage of the bush.

The house-party scene in Auckland in the 60s was also a big deal. Two of the best-known hosts, the velvet painter Charlie McPhee and his wife, Tahitian beauty Elizabeth Tetuanui, threw weekend parties twice a year at Karaka Bay. These would start late Friday night and go through until Sunday. Elizabeth had a large friend group of Tahitian musicians, drummers and dancers that fuelled the party, attracting both invited and uninvited guests. They would put down an umu on the beach below the house. There was music and naked dancing, swimming in the bay and sex in the pōhutakawa groves. God knows what any neighbours thought, although there didn’t seem to be anyone but the McPhees living at Karaka Bay back then. The parties were as famous as McPhee’s glorious velvet artworks — in those days, he was arguably more popular and sold more paintings than Colin McCahon.

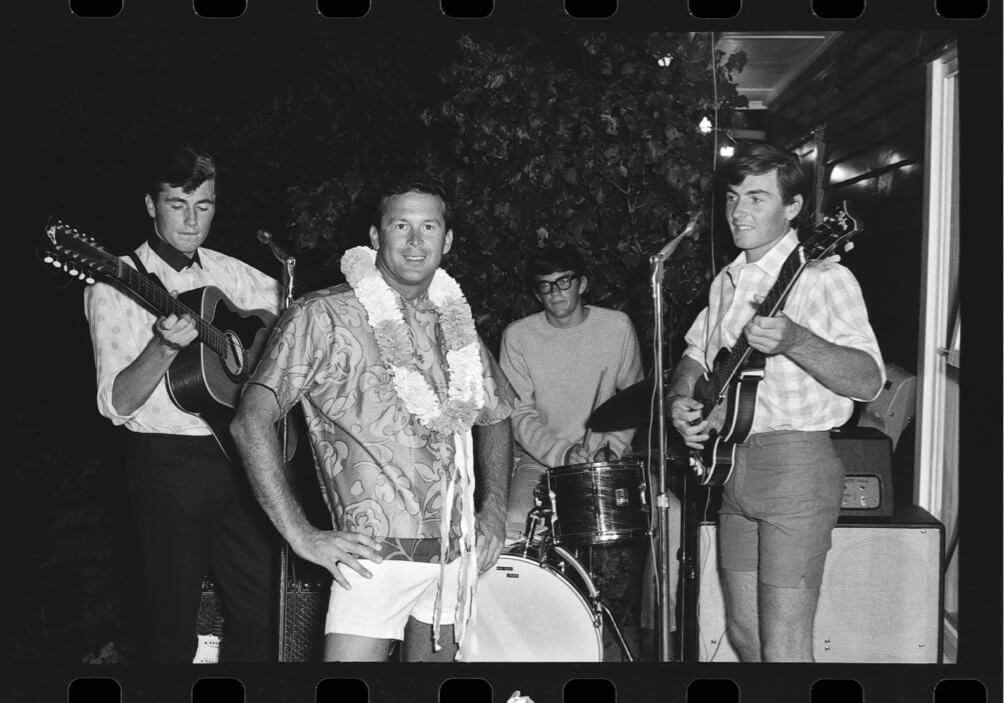

Out at Piha on the full moon, fabric importer Brian Rainger ran with the tag-line ‘the swinging 60s’ and hosted spectacular parties at his testosterone-fuelled bach. Auckland’s models, photographers, designers and the local surf-club hunks were all invited to nights under the moon in January, February and March each year. Rainger’s theme was ‘Hawaiian splendour’ and he’d bring in musicians and dancers and fire eaters to thrill the crowds. The women in bikinis and the bare-chested hunks were immortalised by Arne Loot, Auckland’s first paparazzi photographer, who moved from party to party recording these moments. Loot died recently aged 99, leaving behind 100,000 images of Auckland’s parties in his collection.

The high times of the decade, the enormous changes the 60s saw, proved to be unstoppable. Into our lives came television, Playboy and decent sex; it was the start of newfound freedom in every imaginable way. In 1967, more than 64% of New Zealanders who voted in a referendum backed a change to liquor licensing laws to enable later closing. Fifty years of the 6 o’clock swill came to an end, and New Zealand came of age, ushering in the prospect of further change. The parties continued, but evolved in form through the 70s and 80s. And today, Rainger, who is now 91, has been threatening to revive his full-moon Piha parties. Aucklanders await the invitation.

–

![]()