Mar 1, 2021 Society

Tales of a revenge-seeking whale helped inspire one of the great works of literature. Could the creature have met its end at the mouth of the Manukau?

Auckland in 1861 was a town in fear. Māori were restless in the Waikato. Fort Britomart was on high alert and the Southern Cross, the newspaper that would later be incorporated into the New Zealand Herald, added to the unease with the reporting of Russian gunships cruising the Pacific hell-bent on conquering new territories such as New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. Queen St was a sinkhole, with the Ligar Canal a cesspool of filth, planks and the occasional dead body.

Then, in July, in the heart of a grim and cold winter, came astonishing news. A massive whale had been washed up on the black Whatipu sands. It was found by the harbourmaster, Captain Thomas Wing, the nautical hero of the Hokianga and Manukau harbours. He sent his son Edward to row from the signal station at the Manukau Heads to Onehunga and then, by carriage, to the offices of the Southern Cross to report this astonishing event.

The largest whale ever seen in these waters had come ashore in the massive storm that had swept the country the previous weekend. The sperm whale, reported Edward, had been estimated by Captain Wing to be at least 80 feet long and weighing in the vicinity of 100 tons, but, more than that, it was of a whitish tinge and bore the remnants of at least 20 harpoons in its massive flanks.

The editor immediately held the press for this front-page sensation. Could this be, the paper speculated, the infamous whale that had sunk the whaler Essex in November 1820 by ramming it in an act of vengeance for the harpooning of its pod?

Edward said his father agreed that this could also be the whale that sank the Union in 1807, the Pocahontas in 1850 and the Ann Alexander in 1851. This enormous creature, assumed the paper, had since been roaming the great oceans of the world. The sperm whale is not only the largest toothed predator on the planet, but also has the largest brain of any species. This was therefore a thinking giant, a sinker of vessels and killer of men. It was thought the whale was in its 80th year. Its unique colour was both captivating and terrifying.

The paper reported that any viewing would mean taking one of two steamers from the Onehunga wharf to the mission station at the Manukau Heads, a journey not for the faint-hearted, due to the west coast’s enormous waves. The terrifying Manukau Bar would just 19 months later destroy the steamer warship Orpheus, with the loss of 189 crew.

Still, Aucklanders eager to see the whale headed for Onehunga wharf — then used to ship kauri timber from the mills at Karekare and Piha to the fledgling cities of New Zealand and Australia — and boarded for their passage to Whatipu.

They arrived after Māori, who had travelled from as far as Muriwai and Bethells to greet the whale, setting up an encampment by the dead creature, which by now was oozing thick black blood from its mouth and blowhole. The whale’s massive flukes were covered in barnacles, confirming that this was a creature of great age. And it was deeply scarred, further suggesting that it could be the whale that sank the Essex 2000 miles off the coast of South America. Or was it the notorious albino sperm whale ‘Mocha Dick’, encountered near Mocha Island in Chile and famous for retaliating ferociously to attack? Could it be that here, at the bottom of the world, it had found its final resting place?

Māori reported that on the second night of their stay, the whale gave an enormous groan, then spoke to them. “What did it say?” asked the travellers. The creature said, “Kia tūpato” — beware.

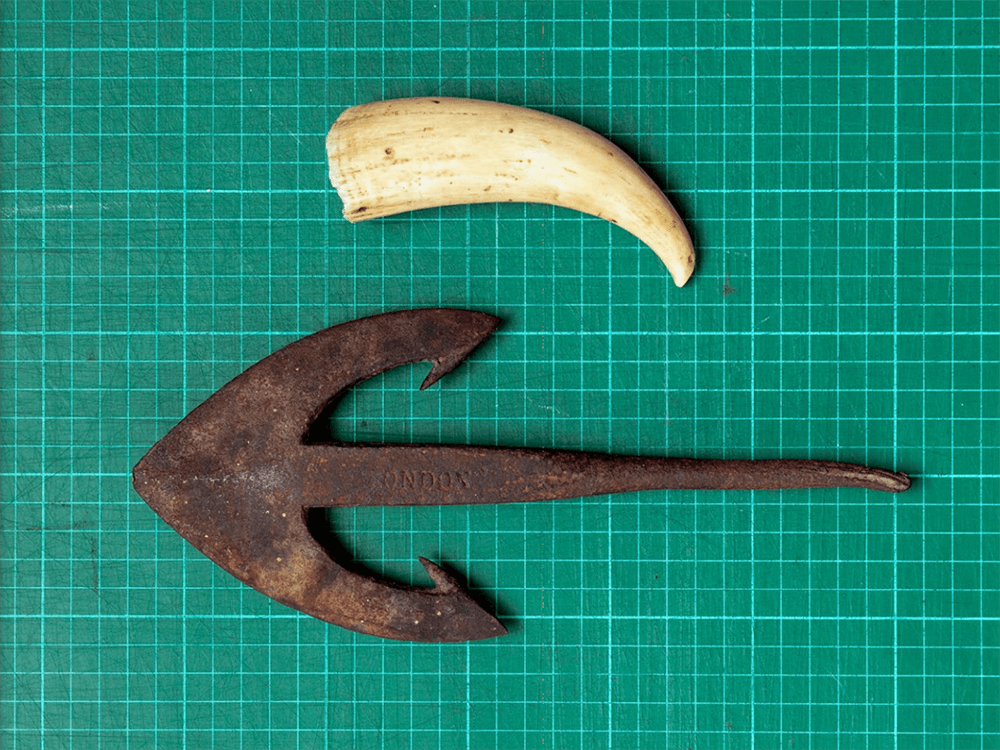

Later, scientists would discover that whales carried enormous amounts of oxygen that would be expelled over days upon stranding — sometimes noisily. But Māori believed that the words coming from the very belly of this behemoth prophesised the end of the world, that death and destruction were coming. They immediately put a rāhui on the creature, though they were too late to save it from mutilation by a group from the fledgling Auckland Museum, who arrived with flensing knives and other implements to remove its gigantic teeth and 10 of the harpoons.

As the week went on, the blubber of the whale began to break down. A putrefying stench blew on the westerly wind. They say you could smell it in Titirangi and even Ponsonby. But still the crowds came. The steamers put on a daily service. The Māori mission at the heads offered guided tours for two shillings and horses for those who wanted to ride the mile around the point to where the whale lay rotting.

The Southern Cross kept a running column on the whale, with correspondence from old sea dogs. Mariners in general — and the British Admiralty — took an avid interest in the creature and its fate on the Whatipu sands.

The arrival of the Governor of New Zealand, Sir Thomas Gore Browne, with his staff, Māori translators and attendants was the pinnacle of this sensational event. Browne pronounced that this was indeed the legendary Mocha Dick, the destroyer of its mortal whaler enemies.

Following Browne’s visit, the skies darkened. The wind from the west rose. Lightning pierced the skies and a ferocious mid-winter storm rose out of the Tasman. Within hours, waves up to 16 feet high were crashing over the carcass, lifting it and pulling it back into the ocean. By the next day, it was gone, reclaimed by the sea.

Across the world, an American novelist, short-story writer and poet had read of Mocha Dick and its quest for revenge. He had also met the son of a survivor of the Essex sinking and gone on to write the book that would come to help define maritime literature. On its publication in 1851, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale was a commercial failure. It was not until well after Herman Melville’s death, in 1891, that it would come to be regarded as one of the greatest books ever written about the sea.