Oct 1, 2022 Politics

Fifty years ago this November, New Zealand elected the most charismatic leader since the legendary Michael Joseph Savage in 1935, who pulled the country out of the Depression doldrums and set it on the path to self-esteem. Norman Kirk would do even more: he would inspire us to take on the world. For a mere 21 months as prime minister, he would captivate and encourage New Zealanders, showing us what true leadership could be. He withdrew our troops from the Vietnam War, abolished compulsory military training, cancelled the 1973 Springbok tour, sent two frigates to challenge French nuclear testing in the Pacific, and made Waitangi Day a public holiday.

Big Norm was a political powerhouse and I had the privilege to work with him and travel the country by his side, often ironing his shirts, polishing his big black policeman shoes, and adjusting his tie. Our friendship was deep and rich. There was nothing we couldn’t share with each other. A trust grew between us and I honour it to this day, though he’s no longer here to share in it. I observed his transformation from a Labour MP with a working-class background to an international star, a catalyst for generational change; from a deeply humble man with a sensitive understanding of our nation’s psyche to a paranoid, withdrawn politician, obsessed with death, shooting at pigeons from his window.

In Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s Beehive office there is a photo of Kirk on the wall. She holds him in high regard as the initiator of a new age of politics in New Zealand. He became a touchstone of this country with his famous, oft-quoted (and misquoted) statement that the four things that matter to people are somewhere to live, food to eat, clothing to wear and something to hope for. I’m proud to have had a hand in his rise and in the creation of modern political campaigns, which can elevate a great campaigner to a political superstar. Kirk had all the necessary raw ingredients.

In January 1968, I had travelled to an advertising conference in California where the guest speaker was the incredible Mary Wells, CEO of the prestigious American creative agency Wells Rich Greene. I did an early-morning workshop on creativity in New Zealand, and she later expressed an interest in discussing my presentation on indigenous advertising here. She invited me to stop by the agency when I was in New York. When I did, she did even more for me than just giving me her time: she gave me a desk for a week, and one evening, she asked if I’d sit in on a creative pitch she and her team were doing to try to win the Richard Nixon campaign account for the presidential election that November. Most of the long night centred on political strategy and a badly needed rebranding of Nixon’s image. By midnight, I was convinced that on my return to New Zealand, I had to use the same model to enliven the dull, overregulated election campaigns that Kiwis had to endure every three years. I was convinced that if I could get a meeting with Kirk, who was then the Leader of the Opposition, I would be able to persuade him that he and the Labour Party could completely rebrand and win the general election in 1969.

Once home, I managed to secure a slot in Kirk’s diary while he was staying at the Great Northern Hotel, his favourite Auckland haunt. The word was Kirk hated advertising — and any hint of market research even more. I was 28 years old and wildly enthusiastic about capturing the moment. I thought there was a unique opportunity to change the face of political advertising in New Zealand. I got my 10 minutes after lunch and after a brief introduction, I told him that I ran a small hot-shot agency and had some brilliant ideas on how the election campaign could be run. My friends in the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band had written a campaign song for me titled It’s Your Turn Now, so I pulled a tape recorder from my briefcase and gave him a taste of it. I told him how the branding would work and I saw his senior party mates nodding along as I talked. A couple of weeks later, at the Labour regional conference in the Auckland Town Hall, I was introduced as the campaign adviser. I showed the conference the new Labour Party logo designed by Dick Frizzell and Hamish Keith. The delegates stood and cheered.

There were other priorities. I made Kirk get a decent haircut. I took him to a High Street tailor and for the first time he got a couple of suits that actually fitted him. I picked out his ties, and bravely asked him to go to a gym. He agreed, and took his mate Bill Rowling, who fainted in the sauna — exercise was then off the menu. It occurred to me that I should attempt to make his size and weight a plus, so I turned him into a political All Black and tagged him “Big Norm”. It stuck, and he was flattered. Our trust and friendship blossomed. In turn, I was known to his senior leadership mates as “Norm’s crazy Auckland ad man”. They liked me because their boss liked me.

The 1969 campaign was considered to be a great success even though Labour lost by a narrow margin. The party liked the split-screen ads, the music and the brilliant, brutal commercials directed by Roger Donaldson showing the futility of the Vietnam War and the plight of the homeless and marginalised. Kirk understood what we were trying to do. He had come from a working-class background in Christchurch, he had been the youngest mayor in New Zealand, and he told me he read a book a day. In Auckland, he had stoked the boilers on the Devonport ferries and at the end of the week he would bike the 120km to Paeroa to visit his girlfriend, Ruth Miller, who later became his wife.

I saw him as a handsome giant with a quietly powerful voice and extraordinary command of his oratory skills. He would often come home with me, where my wife, Barbara, would always lay out the big red tablecloth. The gentle giant would help me put the kids to bed, then we would talk into the early hours on strategy and how the run-up to the election might look.

As we travelled together around the country, we started focusing on how to capture the young vote. In a Rotorua motel room we worked on the development of the Ohu programme to give young people the opportunity to live in communes in remote villages and work to make them sustainable. I was producing Start Again, a documentary on the counter-culture movement directed by Roger Donaldson. Kirk was fascinated by the movement and how Labour could be seen to be paving the road from Woodstock to New Zealand. (He would announce the Ohu programme in October 1973.)

The 1972 election loomed large. Our agency came up with a slogan which we shared with the Australian Labor Party: It’s time for a change. I had reservations about the length, so convinced the Australians to go with simply It’s time. I pitched it to Kirk at a bar in Whangārei. He told me it lacked policy. I told him he would have to take care of that and to leave the rest to me. I had commissioned again a beautiful piece of underscore music by folk rock group Waves. The campaign was a resounding success for the Labour parties in both countries.

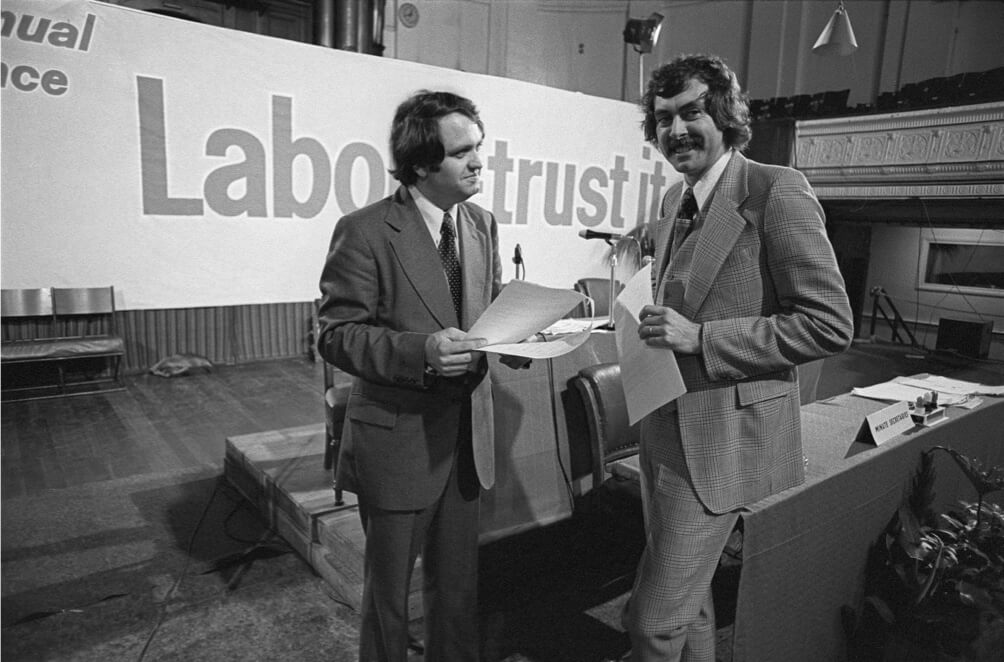

Mike Moore and Bob Harvey

As prime minister, Kirk changed markedly. He lost his warmth and his ease with colleagues. He told me he trusted very few of them, and that the bureaucrats who surrounded him and the Cabinet were “dangerous”. He was convinced that his office and home were bugged by the Security Intelligence Service, and within days he had ordered a sweep of his office. Nothing was found, but he was not convinced. Paranoia was taking over. He was suspicious and Machiavellian. He closed down except to a small circle of advisers, including Mike Moore, who had been elected MP for Eden at the age of just 23, and me. There were long sessions with economist and retired civil servant Bill Sutch, who would come up the back stairs and talk with Kirk late into the night.

Kirk believed in global unity, the futility of war, and the realistic threat of another devastating depression. Britain had abandoned New Zealand for the European Economic Community in 1973, which was forcing us to find new markets for our exports. Kirk told me he would do so by opening the first Chinese embassy in the Western world. He sent a frigate with Cabinet minister Fraser Colman on board to protest against the French conducting nuclear tests above ground in the Pacific, and he was fast becoming a legendary international speaker, picking up friends such as the powerful Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore and Golda Meir of Israel. They inspired Kirk with their tough stances, and the independence of their countries, and he was similarly undaunted at the idea of taking on the future.

In September 1973, America laid it on for this new voice from the Pacific. Thousands of New Zealand flags flew along Pennsylvania Ave up to the White House gates when Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat hosted a state dinner for Kirk — US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had returned from Paris to join them. They were warm and friendly, Kirk said. We should be doing more with them.

It was on that trip, in New York, that rumours he had suffered a heart attack first surfaced. At the time, I thought it was just tiredness, but later I came to think that Kirk knew he was dying and was existentially driven to achieve as much as he could with what little time he believed he had. Back in New Zealand, he would ring me late at night and ask if I would pick him up at the back door of the Great Northern Hotel. Obediently, I would collect him and drive him to addresses in the suburbs, falling asleep while I waited for him. For years, I would try to solve the mystery of who he was meeting and why there was so much secrecy involved. Only later did I come to the conclusion that I was taking him to the homes of doctors who were treating him in private.

I was concerned about conversations with Kirk and Mike Moore about relationships with business, and the Prime Minister’s desire to break longstanding agreements with foreign countries which were essential to our economic future. Much of this was driven by advice from Bill Sutch, who would urge Kirk to cut ties with Britain and other trading partners and concentrate on deals with the emerging Arab world, China and the Soviet Union. This was all before Sutch was accused of spying for Moscow. He was acquitted at the subsequent trial.

I was worried about Kirk’s loneliness, his workload and his isolation from his colleagues. It was said that he had a black book that he was steadily filling up with the names of enemies and prior friends. His office now had a sort of Shakespearean atmosphere, with tragedy and betrayal in the air. He was slowly becoming more and more difficult to deal with, and in mid-March 1974, following a visit by President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, it all came to a head. Kirk and Nyerere had taken an extensive tour around New Zealand, intended to show the president the Kiwi way of life and landscape. It was exhausting, and on 6 April 1974, Kirk entered hospital for what he said was a minor operation.

It wasn’t.

The parliamentary Labour Party, as they had done with the seriously ill Savage in 1940, released false news reports about Kirk’s health. He underwent varicose vein surgery on both legs. Most Cabinet ministers did not know, and those who did felt he was making an error of judgement in having both legs done at once. But Kirk was stubborn and wanted to get it over with. He was photographed sitting up in bed working on Cabinet papers — a PR cover that was far from the truth. Rob Muldoon, the Leader of the Opposition, sent Kirk a message: “Get well quick, Norm, a pensioner needs your bed.”

He was discharged from hospital on 18 April and returned to work, limping on a walking stick and looking dreadful. He tried to keep his feet up, as doctors suggested, but it was agreed he needed to get away from Parliament. A rest at Waitangi was planned — it was hoped he would take a couple of fishing trips and catch some kahawai. The flights taking Kirk, who was stretcher-bound, north and on his return to Wellington were rumoured to be on an unpressurised plane: a fatal error, with his complications of possible blood clots and the fact that he had been taking morphine-based drugs to dilute his blood. A blood clot settled in his right lung, which developed acute pleurisy. He was clearly in dire straits.

On 16 May, in what was a Herculean attempt to show leadership and a return to health, Kirk climbed from his sickbed to attend the Labour Party conference in the Wellington Town Hall. His physical appearance shocked the party; he could barely walk, but the delegates stood and clapped his appearance, cheering him all the way to the stage, where he verged on collapse. It was vintage Big Norm. He had not been near a public platform since early April and here stood the mighty tōtara — with Ruth beside him — holding his now-weak frame on a carved walking stick for support. The Māori delegates gave him a full haka. His white-and-grey-streaked hair was slicked down over his scalp and his face was ashen. It was an unbelievably moving appearance. Kirk spoke for 20 minutes on international affairs, the oil crisis and what he believed was the threat of a growing world depression. It was an amazing moment in New Zealand’s political history.

Over the following weeks, I would visit him. By late August, he would drift in and out of consciousness, then rally and tell me stories, a mix of paranoia and the old Big Norm, as inspirational as ever. He told me he’d be back at work in a month and that a stalker had been keeping him up all night by calling his phone every hour on the hour. I knew things were coming to an end. A week after my last visit, they did. Kirk had been admitted to Our Lady’s Home of Compassion in Island Bay, and on the night of 31 August 1974, at 9pm, he died suddenly while watching the police drama Softly Softly. He was just 51, and had been prime minister for only 21 months.

Kirk at the 1974 Labour Party conference with deputy prime minister, Hugh Watt, MP for Onehunga

The announcement of his death was held until the 11pm radio news bulletin. This delay was very strange, I felt; the late Peter Williams QC told me it had allowed officials to go to Kirk’s office and remove personal details and files, and for the police to get a well-known safe cracker out of Mt Crawford Prison to open his personal safe — no one had the key or combination for it. Clearly, there was also a need to find his black book. The next morning, his Cabinet colleagues were stunned to find his office had been systemically ransacked, papers strewn about and personal details removed.

Big Norm’s death stopped the nation. His state funeral in freezing wintery conditions cast a pall over the entire country. Mike Moore and I, devastated and grief stricken, found it hard to come to terms with the fact he was gone. We tried to get him awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace posthumously but our applications were declined.

I still miss him greatly. I miss his humour, his quiet wisdom, his harshness, his criticism of the campaigns, and his joy at winning. He was a very complex individual. New Zealand honoured him with the planting of tōtara trees in cities and towns — I particularly remember the planting of the tōtara in the old New Lynn town centre. In April this year, following the Anzac Day service at the New Lynn RSA, I walked around the now-unrecognisable New Lynn streets to the community centre, looked up at the huge tōtara that had been planted in his honour, and gently wept.

–