May 3, 2021 Society

From Karangahape Rd to Waiuku — how a quiet powerhouse found her community.

“Have you read a short story by Katherine Mansfield called Miss Brill?” asks Ash Mosen, on the phone from her sewing studio and alterations shop in Waiuku. We are talking about repairing clothing, and how invested people can be in their relationships with their favourite garments. “It’s about this old lady, and every now and then she goes out for a walk. And it’s like all the world’s a stage for her; she’s observant, and she sees all the things going on around her,” explains Mosen.

Miss Brill wears what Mansfield describes as “an ermine necklet” for her excursions, and when she opens the box where she keeps it, the garment greets her. And when Miss Brill puts it away at the end of the day, she hears a little sigh. Mosen loves Mansfield’s imagining of clothing as something personified, embodied. “If I go op-shopping, which I always do, I love to think about where the garments come from,” she says. “They have a history, and they’ve had owners before, and they’ve probably seen their fair share of interesting things. That’s kind of why I love second-hand textiles and clothing that existed before us. And I feel a duty to look after it.”

Mosen is 32 and has brown curly hair and an easy smile. She grew up in Christchurch, and comes from a creative family. Her father has worked as a graphic designer, and is now a self-taught silversmith in his time off from his job working on the docks at Lyttelton Harbour. Mosen wears one of his pieces — a bracelet with fine, hand-hammered chain links — as a necklace. “I’d love to eventually have here in my shop a display of his pieces,” she says.

Her mother, an art teacher, taught students with disabilities at Christchurch’s Allenvale School. “Growing up, being a single mum, she had to make do,” says Mosen, who learned to sew on her mother’s 100-year-old, treadle-driven Singer machine. “She’s always doing things like painting her whole house herself, and always making something out of nothing. She had to be really resourceful with what she had. There was never the — what’s the right word? — the abundance to pick and choose what she wanted to do.” That influences Mosen’s own approach: “Sometimes I get overwhelmed when I have too many options,” she says. “Instead of being like, ‘I need a certain type of fabric’ or whatever, I consider, ‘Well, what’s available to me?’”

After high school, Mosen studied fashion design for a year at Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology, but in her own words, she didn’t achieve much. “I was a bit of a reckless teen, and I was kind of of doing my own thing,” she says. “And I kinda knew most of the stuff they were teaching us, anyway.” She didn’t plan to return for a second year, which was fortunate, because she also didn’t pass. That summer, Mosen came to Auckland for the Big Day Out, and never left.

One night, at a party, Mosen was introduced to the stylist and photographer Karen Inderbitzen-Waller. They hit it off, and Mosen started working for Inderbitzen-Waller assisting on shoots. On one shoot, she met the designer Murray Crane, and he offered her a job on the spot as a junior tailor in the Crane Brothers workshop on High St. Mosen, who was living on Waiheke Island at the time, commuted every day on the ferry to help make suits for “politicians and rugby players”, she recalls. She found she loved sewing special one-off pieces, and the precision and rigour of tailoring.

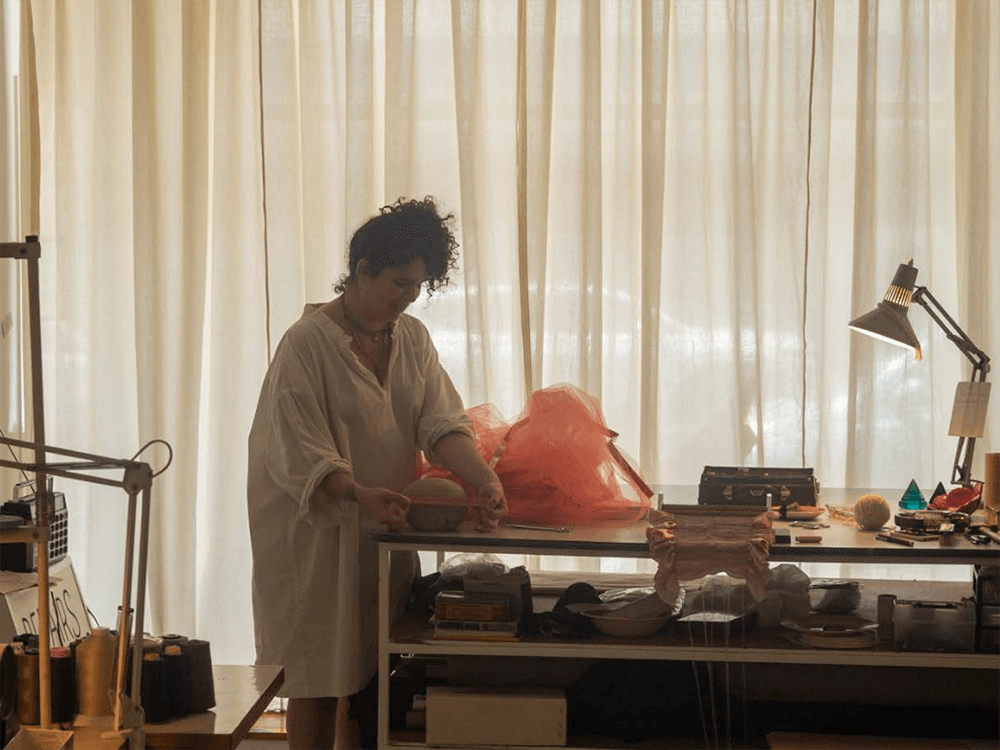

Photo by Andrei Bildarean

“I have always been struck by how inquisitive Ash is,” says Crane, who says Mosen has the unusual quality of being equally fascinated by “the bizarre and the mundane”. And he’s impressed by Mosen’s commitment. “She is fearless in her pursuit of original ideas and has somehow managed to weave a career out of doing something she loves, although I think she would have done it regardless of the risk, reward, or the outcome.”

After two years with Crane Brothers, Mosen moved to Kate Sylvester’s design team, where she worked on clothing and accessories, as well as working in the sample room cutting new patterns. “I got to see everything, from the conception of the garments, to making the prints, to getting that back from the printers and approving it, and then cutting into the real stuff and seeing a garment being formed around it,” she recalls. “Sometimes I would do something sneakily, like if I was doing a repeating print, put my pet rabbit’s name in there,” she laughs.

At Kate Sylvester, she loved the period of intense work right before a new collection was shown. “The energy involved, and early starts and long days,” she says. “Being exhausted, and someone would buy you a great dinner afterwards, and everyone would be happy and exhausted together.”

She was at Kate Sylvester for two years, and after leaving, she thought about starting her own label. But as she took steps in that direction, it felt false to her. “Creating new garments was just — it felt quite wasteful to me,” she says. “A lot of people leave fashion school and they just want to be a designer. But you find that a lot of people don’t actually know how to apply the information that they need to do that. How a garment actually functions, how it works. How the minutiae of pattern-making can change the fit of a garment. I just felt like it wasn’t for me. Because I don’t buy new — I pretty much solely shop at op shops, and make stuff. So when I was making new objects, and churning out a collection, it felt like I was lying to myself. It kinda felt a bit egotistical.” Instead, she quit fashion for a while and worked in a cafe and as a nanny.

Eventually, Mosen moved into a shared studio space on Karangahape Rd and started working alongside the designer James Dobson, who runs the label Jimmy D. “We would just vibe all day, and I would throw my whacked-out ideas at him,” Mosen laughs. She did alterations, repairs and custom pieces, as well as costume work for film, stage, and television productions (none of which she can name, due to non-disclosure agreements). “Ash Mosen is a quiet powerhouse,” says Dobson. “Always hustling, always working on the most eclectic range of projects. Black gallery curtains one day, costumes for a Gloriavale stage show the next.” Dobson remembers a coat Mosen sewed for his most recent show, made out of stiff, reflective silver fabric. “She was literally inside the coat on her sewing machine cursing my name,” he says. “But she finished it impeccably and it’s now hanging on my wall.”

Mosen’s partner owned some land on the Āwhitu Peninsula, and when he decided to build a house on it, she moved her sewing machines out of the city. During the first lockdown, she noticed an empty storefront, a former barbershop, in nearby Waiuku; the rent was affordable, so she decided to open an alterations shop and sewing studio for her costume work, and for a project she has, creating one-of-a-kind items out of vintage garments for the brand Wixii. She also gives sewing lessons. Living in the country and working in a small town has suited Mosen; perhaps unsurprisingly, she’s thriving in an environment with fewer options. “To me, the real community comes from getting away from the city,” she says. “When you’re living in a smaller [town], your accountability goes up … And your sense of purpose increases.”

She loves the variety of the work, and the personal relationships she enjoys with clients. In a week, she might hem a batch of strapless dresses and recycle the leftover fabric into straps, or, for a local archer, turn one of his girlfriend’s old leather handbags into an arm sheath to protect against windburn. “She’s turned her immense talent towards helping people keep their precious clothes rather than encouraging a never-ending cycle of buy, buy, buy,” says Dobson. “She’s so talented, both design-wise and technically, but she isn’t dazzled by the hype of fashion. She’s one of those rare people who’s involved in the industry because she believes in the power of clothing, that it should be made with love and that it should last a lifetime.”

What Mosen loves most about sewing for her customers is the simple act of restoring a lovelorn object to usefulness. “Often when people are really attached to a garment, and you can repair it, it’s worth so much more than your stitches count for,” she says. “Someone sent me a text recently, ‘Are you still healing clothes?’ I loved that!” She laughs. “I was like, ‘Yeah I am. I’m healing clothes every day.’”