Sep 15, 2022 Schools

The fire alarm rings out on the teacher training campus.

Professor Peter O’Connor begins to laugh over the phone. Alarms — false or otherwise — are expected in education, and this siren seemed well timed to the weight of our conversation. I had asked O’Connor to explain what he called art’s “death by neglect” in education. “The focus has been unrelenting in favour of STEM subjects” — that’s science, technology, engineering and maths — “and secondary-school art enrolments are down by a third in New Zealand’s schools over the last 10 years.”

O’Connor makes clear why this precipitous drop — and arts education more generally — matters: “Art awakens us, and teaches us to notice the world.” These are elegant words, but the professor can also speak plainly. “We teach sports and PE not so we can make All Blacks, we teach PE so we have a better understanding of what our bodies can do,” he says. Teaching art should create a similar sense of possibility.

O’Connor was a teacher and pioneering theatre-maker before becoming an academic. I ask what led him to teaching, and his answer is familiar: “I had a bloody good teacher.” Good teachers really can make a difference, small yet tangible, in the changed lives of their students. I wanted to speak to some of these good teachers of art in Tāmaki Makaurau — people who make a difference despite the ‘death by neglect’.

Paul Stevens speaks over the 3 o’clock bell. The distant pandemonium of students leaving class can be heard over the line. Teachers are always pressed for time, and the bell chimes are a constant reminder. I asked Stevens, an art teacher and union organiser in Tāmaki Makaurau, to get me up to speed on the state of art in our secondary schools. “Too often art is seen as a ‘nice to have’ next to STEM subjects,” he says. “There, but not given much priority.” This fits my own experience of four years’ teaching in a UK primary school which eventually removed art from the timetable altogether. Art was seen to be a hassle — resource heavy, and a distraction from maths and English.

Stevens reflects on the position of art in schools. “I think we need a more holistic understanding of knowledge and how the arts fit into the broader curriculum. We need to recognise that art is part of what gives life — and learning — meaning. It connects ideas together and empowers students to look at things differently.” For Stevens, the mission is a personal one. “When I was a teenager and finding things tough, photography provided something of a view ‘out of the closet’ for me.”

Stevens is not alone; we know that art is a crucial outlet for young people navigating their identities. This is particularly important in Aotearoa, where high youth suicide rates heighten the need for meaningful and safe expression for young people. O’Connor agrees, citing a substantial 2019 study from the World Health Organization. “One of the best barriers to mental health collapse is arts in the community,” he says. In O’Connor’s view, “prescribing the arts is cheaper than prescribing antidepressants”.

Speaking as a regional chair of the PPTA, Stevens gestures to this bigger picture. “I am a unionist as well as a teacher, and I see education as a huge lever for societal change.” Teachers are one of the last remaining highly unionised professional bodies, and teachers make a point of advocating for both their work and their students, who — on account of their youth — are politically disenfranchised. It’s a precarious position, one that sees the profession at odds with the neoliberal approach to labour politics, and often butting heads with the government (for example in the ‘mega-strike’ of 2019).

Even in the relative refuge of the art classroom, you can’t escape the inequality that has gripped Aotearoa. As a teacher who has worked across the decile ranges, Stevens reflects that “art often requires expensive resources, and as such we do see art departments as a particular area of inequity between schools, further reinforcing broader inequities”. NCEA results reflect that hard truth — last year, only around 12% of NCEA Scholarship awards across the arts came from schools in deciles 1 to 3, which serve roughly 25% of our student population.

Pilimilose Manu is an art teacher at Liston College, and the job has a personal element to it for this former student of the West Auckland Catholic boys school. He’s good at what he does, too; the art teacher community raves about his Instagram page ‘creativeculturalvation’, and his former students are frequently among the ‘top in country’ recipients. “People assume teachers’ roles are solely to teach, but we also take on the role of the ‘older brother’, ‘sister’, ‘parent’ and ‘counsellor’,” he says from an art supply cupboard, the type of quiet refuge coveted by teachers. “This care can become mentally and emotionally draining.”

Manu looked tired — it was the last Friday before end of term. “After six years of teaching I am finding it particularly difficult to find the same excitement I had as a first- year teacher. I have put this down to frustrations around management, class sizes, multilevel classes, underfunding. [Being] undersupported, overworked, the dumping ground for difficult students… The list goes on,” he says. He’s not alone in his feelings. Concerns over teacher retention has been a national issue in the past decade (though recent figures from the Ministry of Education suggest improvement).

There’s no denying that it’s a hard job. Art teachers have to summon connection and spark a creative process with young people who are going through the hard years of adolescence, all the while maintaining engagement with complex (and sometimes dysfunctional) institutions. More often than not, teacher ‘burnout’ (a notorious phrase in the education sector) occurs because of the complexity of adult interactions — parents and teaching faculty prove harder to deal with than even the pubescent teenagers. “At present the part of the job that I enjoy is talking with the students, they make the job less stressful,” says Manu.

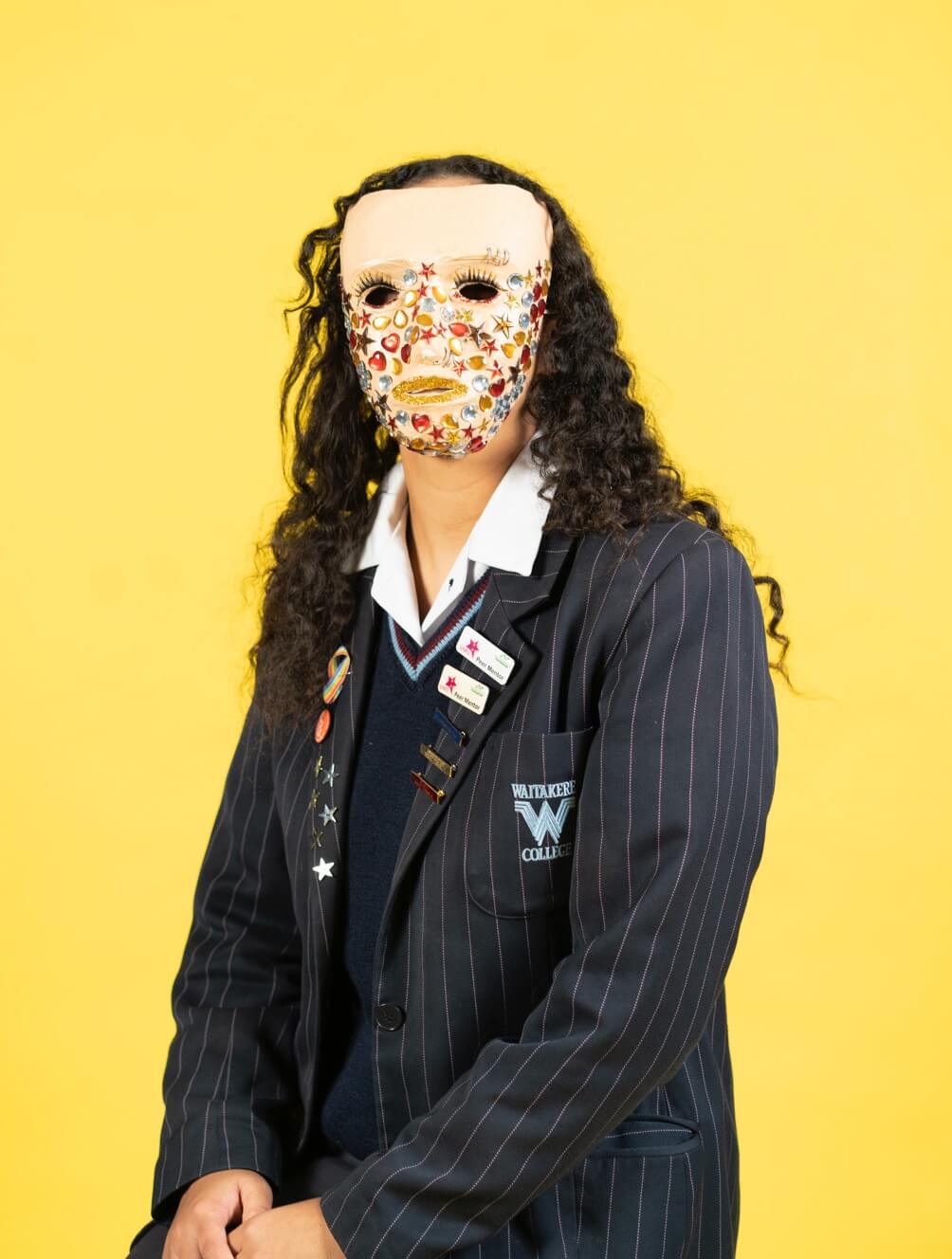

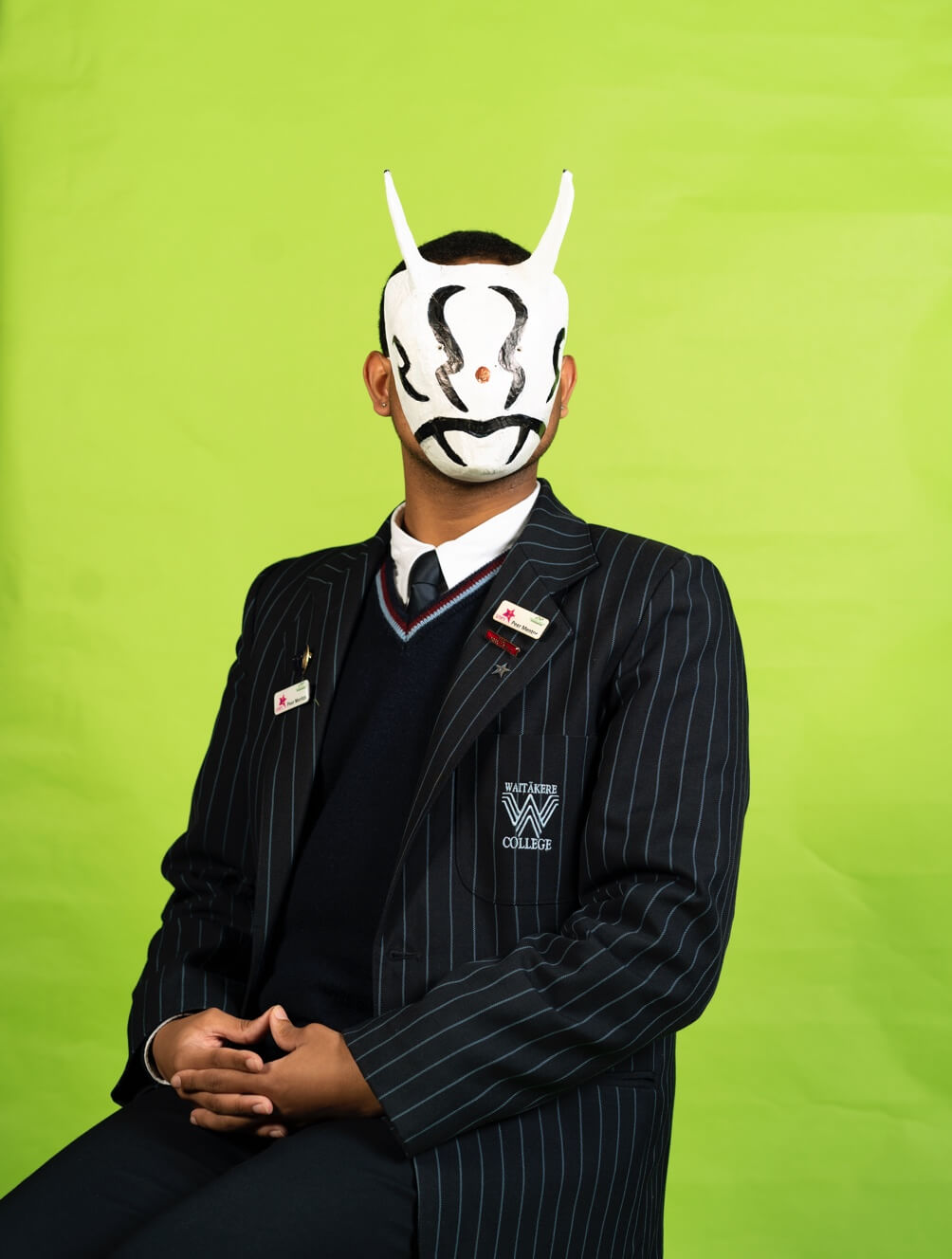

Manu’s style of teaching (emphasising one-to-one dialogue) is disarmingly informal and attuned to talanoa — a Moana concept of talk and exchange. The students emerging from his classroom are impressive. Their work is innovative, personal, technically accomplished and conceptually deep — in some instances, they are achieving at a level more appropriate for master’s programmes. Manu has a clear view about how to reach this achievement. He incorporates university-style teaching (such as critiques), to “move [students] away from the high-school style aesthetic — from the literal to conceptual”. Manu also sees other ways of borrowing from the university, advocating for “exhibition-styled submissions that would better prepare students for art school”. I like the idea. For one week in early summer, our gymnasiums could become art galleries, offering communities — and examiners — an opportunity to view the next generation of artists and their work.

Edith Amituanai is at the back of the class as I arrive at Birkenhead College. Amituanai is not a teacher — not in the strictest sense of the word. She is here as part of the Creatives in Schools programme designed to place practising artists in mainstream schools without the rigmarole of teacher training. As I watch Amituanai pick out her favourite books from the teacher’s impressive art library, it’s easy to forget that she is a distinguished artist and a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit. Quick to praise the daily work of teachers, Amituanai describes her role as “the creative aunty at school for the day”— humility in spades.

I ask her to fill me in on new trends in adolescent art. “Since Covid, I’ve noticed a reinvigorated interest in nature that includes unpeopled cityscapes, sunsets, flowers, mountains, oceans. An investigation into your cultural identity never gets old.” I share a memory from my own art class of a lot of people painting cars — “Oh I love the car boards. Hard to do well though.”

As an educator, Amituanai is full of service and care — like an attentive studio assistant and life coach rolled into one. Young people, often lacking in confidence, need to feed off the belief of those around them, and Amituanai provides it, with a string of real and precise encouragement where needed. The approach reminds me of Manu’s one-to-one chats; the students seem to grow under the attentive informality. Always kind, Amituanai is nevertheless clear about her expectations for the students. “There’s nothing like being yelled at by a professional photographer for missing your deadline!”

Discussing her process in the classroom, Amituanai explains the “bag of tricks” required “to counter the range of challenges that arise […] Sometimes a student may need a ‘give it to them straight’ approach, while others need a class discussion.” At heart, it’s about knowing your students. Clearly, the presence and perceptivity of

a practising photographer also finds a natural home in the classroom.

The Creatives in Schools programme has its roots in the lauded Temporary Employment Programme (known as ARTWORK) of the 1980s, that saw pivotal New Zealand artists working in schools, painting public murals and creating work for public collections. The idea is simple: artists need work, and their work has value in the community.

Across town at Ormiston College, Tara-Lee Soysa is enjoying a moment of respite from Sports Day. I ask the school’s leader of visual arts what she would ideally be doing on the day that’s all about athletics. “Probably banner-making,” she says.

The clock is always ticking, and Soysa gets stuck into the conversation ahead. “Covid has been a huge challenge for art teaching. Especially when looking at something tactile like painting — that hasn’t been able to take place for two years! […] It has meant a lot more video tutorials and demonstrations.” The media coverage of Covid’s educational impact tended to highlight its deleterious impact on STEM subjects, but art requires presence, and art education is largely incompatible with the ‘transmission model’ of Zoom learning.

It’s not long before Soysa’s lunch break is coming to an end, and she leaves me with an aspiration. “We could have secondary schools that were specifically for the arts, and then have key subject teachers who could collaborate with art teachers to teach math and English.” It’s a nice idea, and has precedents in Australia and the United States. Soysa recalls her own education in Ngāruawāhia, explaining, “I missed lots of my other classes in high school so I could go to art. Well… I want a school where you’re allowed to do that.”

Over the following weeks, the idea of this secondary ‘art school’ emerges further in emails between us. There would need to be more flexibility in the timetable structure, and the architecture of the school could be reimagined around the needs of art. There would be plenty of opportunities for community engagement, too, with practising artist educators contributing in a more long-term way than in the Creatives in Schools programme. Most exciting of all, this type of school could host other schools too, sharing ideas and facilities that could support the broader system.

Maraea Timutimu (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Tūhoe) taught at Western Heights High School for nine years before deciding to focus on her own art. Speaking from her home in Tauranga, Timutimu reflects on her journey in education — while attending a Māori girls boarding school in Parnell, her formative years were shaped by “strong female role models in the powerful legacy of Māori leaders”. Timutimu wanted to be an artist, but: “My mother encouraged me to get into teaching because I’d be able to make art everyday.” Timutimu laughs .“Thinking back, she may have tricked me.”

Timutimu assures me that when it comes to art and education, she “would be lost without both”. While she’s grateful to be spending more time in the studio, she explains that it’s a trade-off. “I miss the Māori students in the mainstream schools, especially those who may not know much about their whakapapa. Most Māori students are in mainstream schools, and teaching in that context with a supportive and inspiring art department was a privilege.” Timutimu’s recollections are filled with stories — inspiring and commonplace — of the things good teachers do to connect with ‘hard to reach’ families, working weekends, evenings and holidays if necessary. It’s tough to sustain, but especially frustrating is the work that takes a teacher “away from [their] teaching practice”. Timutimu explains further, “There were times where I felt leaders required certain things from me [reports, surveys, evidence gathering and data analysis], and I couldn’t always see the benefit of those requests.”

On the persistent disadvantage faced by Māori students in education, Timutimu reflects that Māori knowledge and language is “held in our taiao, in our bodies and in our art. Thinking about equitable outcomes for Māori, I wish schools would value the arts as highly as other [core] subjects. Art is an essential part of mātauranga Māori. Whether through haka, mōteatea or poi, art is how we share our narratives and stories.”

Timutimu continues to keep one eye on education, and has strong opinions on the proposed reorientation of NCEA towards mātauranga Māori, which includes an ex- pectation that all teachers be able to support its teaching. “If mātauranga Māori is a focus for NCEA, then changes need to be backed up with time and money. As long as mātauranga Māori is the focus, then Māori must always be part of the equation. Don’t develop Māori expertise and then get rid of them once the NCEA changes have launched.”

According to the Ministry of Education, there are currently no plans to create a new position in schools to liaise with iwi and community, presenting the real likelihood that the revised NCEA focus on mātauranga Māori will struggle to engage the diversity of te ao Māori across Aotearoa.

In speaking to the art teachers of Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond, recurrent issues emerge within the profession. Practical things like the obscene cost of transporting art boards to examiners. Concerns over the provision of professional development to support a renewed emphasis on mātauranga Māori. And, perhaps most importantly, worries about leadership. The importance of good leadership in schools is difficult to overstate, and the arts live and die by the values of senior leaders. Effective, compassionate and informed leadership is often touted as the single most defining difference in school performance. For the arts, this is doubly true, as ill-informed leadership may struggle to understand the value of the subject altogether.

I think back to Peter O’Connor training the next generation of art teachers on the Epsom education campus — the alarm still ringing in the distance. As a theatre-maker who works in spaces of social crisis, he knows the trouble creativity finds itself in. “Much of what happens in our society anaesthetises us — makes us numb. The opposite of ‘anaesthetises’ is aesthetics.” For O’Connor, creativity seems to offer a real response to many of the ways of thinking in capitalist society. I like his hope.

“When I went into teaching, there was greater freedom in classrooms to be imaginative and creative,” O’Connor explains with a tone of sympathy for his training teachers. Summarising the changes over the past 30 years, O’Connor describes “a bureaucratisation of education”. He warns that “if teaching isn’t a creative act, it’s soul-destroying”. O’Connor’s words hit me personally. In the United Kingdom, where the education system was rapidly dispensing with creativity, I had come close to experiencing that dreaded ‘burnout’; come close to being another dreary statistic of teacher retention.

The professor reminds me that hope is a moral obligation (while citing Immanuel Kant), and points to the great work being done here. “There are extraordinary art teachers in Tāmaki Makaurau, and they’re often working in isolation and without adequate support — fighting the good fight all over the city.” O’Connor sings the praises of the teachers I’d met. “Teachers are on the frontline of a war created by poverty and inequality, and it is enormously exhausting for them.” I thought of Manu, achieving scholarship grades with his students, but also seeking refuge in the art supplies cupboard.

The clock is always running out on our education system, but teachers, properly trained and supported to be leaders in the community, offer meaningful resistance. The best educators have a way of suspending time around them, ignoring the clock and giving pause and presence to those in their care. Still, the alarm is ringing, sounding out our society’s deterioration in mental health, the challenges of the labour economy and the ongoing trauma of a setter nation. Art offers ways of attending to this and, moreover, it offers the intangibilities that make life worth living.