Jan 12, 2021 Food

In steamy kitchens across Auckland, immigrant cooks try to recreate the flavours of food they grew up with. Metro profiles four restaurants that deliver on that promise — to the delight of fellow expats, and anyone else in on the secret.

Momo Junction | Gold Ribbon | Just Plove | It’s Java

Sushmita and Rahul Pakhrin, owners of Momo Junction. Photography by Edith Amituanai.

Momo Junction

Sushmita and Rahul Pakhrin

Shop 2/360 Great North Rd, Henderson

The city of Darjeeling, on the northern tip of West Bengal in India, clings to the Himalayan foothills, at 2000m above sea level. Momo Junction co-owner Rahul Pakhrin points to a photograph of his home city — clustered buildings painted in washed-out pastel and stripes of vibrant yellow. Over the speakers, a chant, common to Tibetan Buddhism, plays to ward off negative energy; om, ma, ni, padme, hum. Other photos on the wall show Darjeeling’s famous tea estates and the blue ‘Toy Train’ of the Himalayan Railway. There is, obviously, great pride and care in sharing where they come from.

Only two months ago, Sushmita Pakhrin, Rahul’s wife, and co-owner and head chef of Momo Junction, was working at a shipping company. “Opening a restaurant was always in the back of my mind,” she says, “but it just clicked this time.” Sushmita is not a trained chef, but a home cook who saw the demand for a place which serves the traditional food found in the Himalayan region — somewhere people from back home could come and eat the things they miss. Neither Sushmita nor her husband have hospitality experience — Sushmita hadn’t even cooked in a commercial kitchen before. And yet, she says things are falling into place. “You know, my husband is a vegetarian, so he’s never even tried the non-vegetarian food that I’ve cooked,” she laughs. “But he still had the trust in me. He said, ‘why don’t we start a restaurant?’”

Darjeeling’s cuisine is a mix of fare from neighbouring regions in the Himalayas — Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, and Sikkim. Their central dish, the momo, is a dumpling that has a completely different flavour profile to that of its Chinese counterpart — heavier on spices, and often served with a unique tomato-chilli sauce. Every restaurant in Darjeeling serves them, and every household in Darjeeling knows how to make them. The version here is specific to Darjeeling — the filling differs slightly, even from its sister over in Nepal. “When you think of Indian food, you may think of curry,” Sushmita says. “But we don’t have any curries here. Our spices are really different too.” This region’s cuisine is not as ubiquitous in Auckland as food from other areas in India, so people will come in without ever having had the cuisine before. But there are some similarities to other dishes New Zealanders are familiar with, touchstones that may help them to understand the cuisine. For example, the shafaley is kind of like a Tibetan meat pie, encrusted in puff ed-up deep-fried pastry stuffed with savoury minced meat; and Pakhrin’s personal favourite, the thukpa, is a chicken noodle soup, but with soy sauce and spices.

The Darjeeling community in Auckland is small. That’s another reason the couple wanted to open the restaurant — so that their kids, aged five and one, who were born in New Zealand, are able to further connect to their roots and their community. “There are probably only about 20 families here,” she says. “Everyone knows each other, especially in Auckland.”

Til Ko Achar (Sesame Chutney)

This spicy-sesame chutney til ko achar is Darjeeling-style. Enjoy with momos, rice or… actually, it just goes along with anything.

Ingredients

2-3 large tomatoes

2-3 cloves of garlic

75g white sesame seeds

5-6 dry red chillies

Salt to taste

Roast tomatoes on an open flame on a gas stove. (Roasting on open flame gives smoky flavour to the tomatoes.)

Peel the skin off the tomatoes.

Roast dry chillies in a pan on low flame and keep aside. In the same pan roast sesame seeds on low flame until they turn golden brown. Make sure they don’t burn.

Put all the ingredients in the blender, add salt to taste and blend.

Mitchie and Ronald Ricafrente, owners of Gold Ribbon. Photography by Edith Amituanai.

Gold Ribbon

Ronald and Mitchie Ricafrente

1 West Coast Rd, Glen Eden

When Mitchie Ricafrente opened Gold Ribbon in 2013 with her husband and head chef Ronald, she would never have called herself a baker. These days, she makes up to 200 cakes a week, carving out an hour every morning to churn out sponge cakes in flavours like ube, mango, pandan, yema and more. “When I’m in the restaurant, my husband is my boss,” Mitchie laughs. “So when we opened, he was like, ‘You’re going to have to learn to bake!’”

The couple were high-school sweethearts who moved to New Zealand from the Philippines because they wanted to be around family already here, starting work at Richard’s brother’s cafe at Unitec. Every weekend, the family would make Filipino dishes, which served as a launching pad to eventually opening their own restaurant.

The Philippines is made up of around 7,641 islands, so the cuisine shifts from region to region, and conceptualising what Filipino food is can be complex. Ronald is originally from a small province called Marinduque, sometimes known as “the heart of the Philippines”. If you look on the map, you’ll see why — the shape of the island resembles a human heart. Gold Ribbon’s food mostly takes inspiration from the middle region of Philippines, which you can see in the way they cook classics like adobo: traditionally, with soy sauce, salt and vinegar.

Opening the restaurant was tough. Ronald’s brother works alongside him in the kitchen and the rest of the family wade in when needed. Through the years it’s become easier, Mitchie says, now that they’ve settled into a daily routine: up at 5am, drop the kids, head to the Asian supermarket to shop for the day. And then the baking starts.

In the 2018 New Zealand Census, 72,612 people identified as Filipino, 45% of them living in Auckland. Ronald says people will come in from places like Wellington and Christchurch, especially during the holidays. Although Filipinos are the third most common group of Asian-New Zealanders in the country, it’s much harder to find Filipino restaurants than, say, Japanese or Thai. But, there are Filipino community groups, like Pinoys in NZ, where home cooks often sell Filipino specialities to fill the gap.

On the day we visit, Ronald cooks us dishes like sisig, dinuguan (pork blood stew), sinigang (sour soup) and pinakbet (stirfried vegetables in shrimp paste), with a well-practiced ease. Fish sauce (the Squid brand — if you know, you know) is squirted liberally in most dishes, and the smell from bubbling kare kare sauce, sizzling pork, and fragrant shrimp paste is rich and generous.

At home, Ronald prefers something a little simpler, like a pork chop marinated in soy sauce, lemon juice, some sugar and tomato sauce, and cooked on the grill. Still classic Filipino flavour profiles though. He can’t help himself.

Yuri and Farida Tigay, owners of Just Plove. Photography by Edith Amituanai.

Just Plove

Yuri and Farida Tigay

433 Dominion Rd, Mt Eden

When Yuri and Farida Tigay decided to add an ‘e’ to plov, the name of a Uzbek rice dish, the Russian community weren’t happy. They didn’t understand the play on words. “We received a lot of comments on the spelling,” Farida tells us. “Russian people are very straightforward — they will not hesitate to let you know if you do something wrong.”

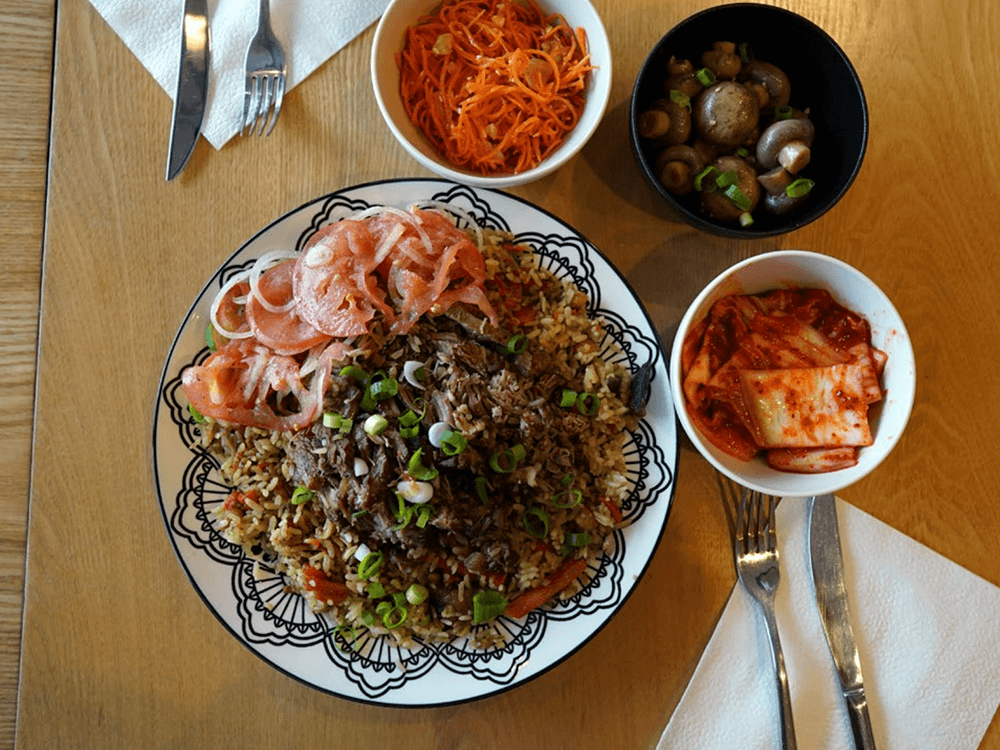

Yuri and Farida are from Kazakhstan, but some of the food they cook is borrowed from other Central Asian and Eastern European countries, like plov (traditionally from Uzbekistan) and borsht (originally from Ukraine). “We don’t position ourselves as a Russian restaurant,” Farida explains. But the Russians have come anyway — many of their customers are from the former Soviet Union countries (“Russian speakers,” Farida says). In Kazakhstan, Russian is still the primary language, though there have been recent initiatives to revitalise the Kazakh language.

When the couple arrived in New Zealand with their three kids (now 14, 11 and eight) a representative from the Kazakh community came to meet them, showing them around the city. “We didn’t expect New Zealand to be… slightly boring,” Farida says, diplomatically. Having travelled to the United States beforehand, she was expecting something similar. Despite not really knowing anything about New Zealand, the couple moved to provide a better life for their kids, especially as they saw, Yuri says, that New Zealand was ranked number one on the Corruption Perceptions Index table. Kazakhstan is ranked 113.

Opening the restaurant was an unexpected necessity, coming off the back of two job losses; the biodiesel project that Yuri was involved in as lead operator had closed and Farida had lost an English-teaching role, along with 37 others. Without having any restaurant background or formal cooking training, the two snapped up a site that had been left in disarray due to a quick exit from previous owners and plunged right into it, cooking the kind of food they’d grown up with and made at home. Yuri is the primary chef. “For plov, I use a step-by-step recipe,” Yuri says. “In the oil-and-gas industry, it’s very important to follow procedures.”

Though they were born in Kazakhstan (Yuri in Atyrau; Farida in Taraz), both have roots from elsewhere. Farida’s parents are from Tatarstan, a country in the Russian Federation, who are culturally close to the Turkish. Yuri, a third-generation Kazakh, is ethnically Korean — a community in Kazakhstan known as ‘Koryo-saram’. “In 1937, before the Second World War, Stalin moved Korean people from the Eastern border of the Soviet Union to Central Asia within three days,” Yuri says. This is how ‘fusion’ dishes — like the Central Asian take on kimchi, served at the restaurant — came to be, as the Koreans adapted their own cuisine to the ingredients they could find in Central Asia.

Farida says she’s finding that some locals, unfamiliar with the cuisine, are afraid to give the food a go. Compared to East Asian cuisine, Central Asian food is plainer. For example, in plov, they have few spices beyond the usual suspects — just turmeric, cumin (ground and seeds) and chilli pepper. Farida hopes to add more authentically Central Asian dishes to the menu in the future, such as manty — big steamed dumplings stuff ed with lamb — or kuksi, a Kazakh-Korean noodle soup.

The plov and side dishes at Just Plove. Photography by Edith Amituanai.

Buckwheat Porridge with Chicken

Ingredients

350g chicken breast

150g roasted buckwheat (Only use buckwheat sold in a Russian speciality store — green buckwheat won’t work.)

1 carrot

600ml water

1 onion

Salt to taste

Cut the chicken in pieces and season with salt and pepper.

Peel and wash the onions and carrots and chop. Wash the buckwheat.

Add oil to the pot then add the chicken, carrots and onions. Cook for 7–10 minutes. Stir several times while cooking at medium-heat. Close the pot lid, and lower the heat. Cook for another 5 minutes.

Add the washed buckwheat, salt and enough water to reach 3–4cm above the buckwheat. Close the lid, add a little more salt and cook for 25 minutes, until the buckwheat is soft.

Variety of dishes at It’s Java. Photography by Edith Amituanai.

It’s Java

Adriana and Bobby Ferdian, Zemmy and Yanti Wahyudi, Wawan and Dana Darmawan

16 Vinegar Ln, Grey Lynn

“We have thousands of islands in Indonesia, so there’s many different sub-cultures and different dialects,” Adriana Ferdian says. “But the consistent thing across all of us is sambal.”

Sambal is a chilli paste mixed with ingredients like shrimp paste, sugar, and lime juice and varies heavily from place to place — there’s about 300 diff erent types in Indonesia alone. At It’s Java, the signature sambal is served in numerous dishes, on the side for others, and in a take-home jar. In many ways, it is the lifeblood of the restaurant.

It’s Java is owned jointly by three husband-and-wife couples. Adriana and Bobby Ferdian handle marketing and branding; Zemmy and Yanti Wahyudi are on day-to-day operations; and Wawan and Dana Darmawan are the chefs who create the dishes on the menu. Everyone grew up in Indonesia and are brought together by a need to create a space for the authentic food and culture they grew up with. “We saw there was no real Indonesian food presence in Auckland — at least none that are our style,” Adriana says. “We wanted this to be a hub for Indonesians to come and find each other for food, chats, lols, and also for jobs; we have a big Indonesian student population here. We know their taste. We know they like their sambal spicy.”

Although they originally served New Zealand-style breakfast food at the beginning, the menu is now pure Indonesian — specifically, pure Java. The chefs, Wawan and Dana, both come from there — Wawan from Surabaya and Dana from Bogor. While working in New Zealand kitchens, neither had the chance to cook their own food. Now they can, using recipes handed down from their ancestors. “Even the plating and the presentation is meant to look like street food,” Wawan says.

Adriana says one of the biggest cultural differences she notices between New Zealanders and Indonesians is in cutlery; Indonesians grow up with a fork in the left hand and spoon on the right. For dishes like nasi campur (mixed rice), they eat with their hands, in a very specific way, different to other cultures. “Indians, for example, use the roti to scoop up their food. We make a mound — mound of rice, a little bit of sambal, bit of meat.”

“We want to introduce how we eat, so we’re not ashamed in encouraging other people to do the same,” Bobby says. “People generally don’t know what Indonesian food is apart from mee goreng packets,” Adriana adds, laughing. “Our menu has been pretty authentic, and we’ve been quite true to the whole idea of, ‘Hey, I’ve grown up eating this food and Kiwis might not know or understand it, but we’re going to see what they think, anyway.” An example of this is the black beef soup (rawon), which is made using black nut (buah keluah), giving the broth an earthy, nutty taste. “It’s all about educating the wider New Zealand people.”

This story was supported by funding from Asia New Zealand Foundation Te Whītau Tūhono.