Sep 29, 2023 Metro Eats

Hello,

Goodbye, readers! I’ve thoroughly enjoyed being in your inboxes every week (ish) for the past three years, telling you about the new places that have opened in Tāmaki and what I’ve thought about the food I’ve found there.

Our latest issue (and my last) will be out on stands this Monday 2 October – please pick one up. I know that avid Metro readers may be expecting Restaurant of the Year based on our cycles, but we’ve unfortunately had to postpone it. So while I’m sad not to end on that particular high note, the new issue contains plenty of “high note” worthy material. Promise.

Truth be told, I’ve been so emo the last week or so that the new Olivia Rodrigo album has been my commute soundtrack of choice (‘bad idea, right?’ is really excellent for angsty moping). Saying a final bye to Metro is proving harder than anticipated, for many reasons, but mainly because of the people I work with. To Henry and Simon: sorry for leaving, thank you for everything. I feel very grateful to have worked within such a tight-knit core trio that didn’t devolve into us all hating each other. I’ll miss you! To Anna, Metro’s beloved sub editor: I hope you’re reading this and finding only a few mistakes. And thank you to everyone else (Metro people, contributors, chefs, photographers, publicists) that I’ve worked with. It has been the best time!

To all those wondering, I’m off to be the Communications and Engagement Manager at not-for-profit organisation Able – a great org that is working towards a more inclusive Aotearoa through the provision of media accessibility services, including captioning and audio description. It is something very different and new and exciting (although, not brand new, as I’d previously worked at Able five years ago, producing the captions!).

My goal is to write about food (and maybe even other stuff) when I can, so if you have an idea for me or want to reach out, you can get me at sjeanteng@gmail.com.

Oh, and: Jenna Wee, host and creator of the podcast Asian in Aotearoa, invited me as a guest on their latest episode. It’s the first time I’ve ever been interviewed, really, so I couldn’t stop talking, and it clocks in at a lithe 65 minutes. Give it a listen on Spotify here and help ensure mine is not the lowest-listened-to episode (lol).

And, as promised: the long, self-indulgent newsletter awaits you below. Please don’t feel like you have to read it all. Here is a helpful summary so you can pare it down to what interests you.

- Giveaways!

- What’s new

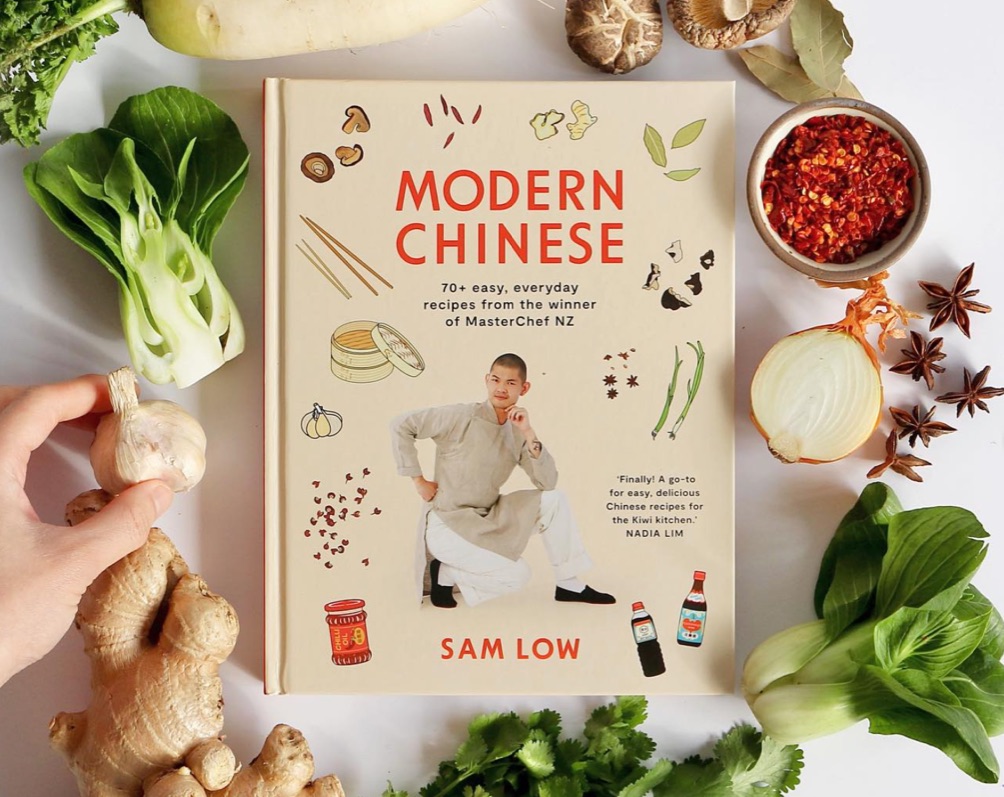

- Interview with Sam, whose cookbook Modern Chinese is out on October 3

- A personal essay redux

– Jean

P.S. A special thanks to Simon, who has illustrated these newsletters and prepped them every week since the very beginning – especially as you do it in such a crazy manual and time-consuming way. I hope you’ve remembered to italicise all the Metro’s in this introduction.

P.P.S. Tomorrow is the last day to apply for the Food Editor role. Rest assured, Metro Eats will continue under whoever gets the role – plus the team will fill the gap in between!

Giveaways

To say thanks to all of you, for reading my words and supporting them and generally allowing me to do my job, I’ve whipped together a few small giveaways featuring some of my favourite things.

To enter, please send an email to jean@metromagazine.co.nz with the Subject line of which giveaway you want to put your name in the draw for. If you want to enter more than one giveaway, please send individual emails. You can enter all of them if you like.

All entrants must live in New Zealand. Entries close 9am Monday 2 October.

Subject line: Metro Eats Faves

Four vouchers to some of my faves, including:

1x $100 gift voucher to Pici / 1 x $100 gift voucher to Sim’s Kitchen / 1 x $100 gift voucher to Ajisen Ramen / 1x $100 gift voucher to Tempero.

—

Subject line: Modern Chinese

1x signed copy of Modern Chinese, by Sam Low / 1x jar of chilli oil, homemade by Sam.

Note: You must be able to pick this prize up from Auckland Central. For a full interview with Sam, see below.

—

Subject line: Lunch break

Three-month Lucky Dip Kōkako Coffee subscription (fortnightly delivery, 200g) / $70 gift voucher to Florets / One-year print subscription (four issues) to Metro magazine.

What’s new

Stracci, the new fresh pasta delicatessen in Westmere that I mentioned a few newsletters ago, is open now at 170 Garnet Rd. Its cute deep-blue storefront opens out into a compact, simple interior, where the star of the show is its cabinets of hand-filled pastas like agnolotti and tortellini. You can also pick up fresh sauces, freezer meals, and desserts.

There’s a new Ethiopian restaurant in New Lynn called Jebena Ethiopian Coffee House, which you can find at 3100 Great North Rd.

Palato Pasta, the tiny pasta stall in the Queens Court food court in central city, has moved and opened a new space in Browns Bay, of all places. Located at 1A/4 Bute Rd, the new spot is much, much bigger – an actual restaurant now, with chairs, wine glasses, and table service.

A new Tsujiri is now open in Albany, at 59 Corinthian Drive.

David Lee simply will not be stopped.

Jean Talks to Sam (Again)

Modern Chinese

I remember you saying to me once that, if you think about the Chinese cookbook canon in New Zealand, there’s really not much that has come before this [Pors Por Cookbook by Carolyn King being one example]. That’s despite Chinese immigrants having a huge impact on New Zealand’s food and cuisine – how do you go about operating within that context?

I didn’t walk into creating the book with the mindset that I’m creating a book that is one of a kind, or the first of. No one wants to be the first of, really. But I did see a gap in the market. Then I thought it was a no-brainer to create a book that also involves the community as much as I can, but also to make it encouraging – to celebrate the different types of Chinese cuisine out there from regional differences to diasporic cuisine.

Do you feel any pressure at all?

I don’t feel that pressure because I’m not speaking on behalf of people, but speaking of my own lived experience. The first thing I have to state is I’m not here to represent the monolith. I think there’s so many cookbooks now called “Modern Asian”, but you can’t really group something like that that’s so vast or diverse – you wouldn’t see that with other cuisines. Like you wouldn’t see “Modern European”. With Modern Chinese, I’m speaking from being modern Chinese, rather than a monolith.

What is modern Chinese, though?

Culture is fluid. When you approach culture with that in mind, you understand how things evolve. For example, Chinese food in Aotearoa has gone through so many influences of other cultures, but has also been influenced by what’s in the land, then limited to the ingredients brought into the land – that in itself becomes modern Chinese. And anyone can cook modern Chinese food, I don’t think food should be gatekept in that way, unless you’re money hungry [laughs].

Why don’t we have a wave of modern Chinese restaurants, then, do you think?

I think we’re in an interesting time right now, where people in the diaspora are starting to embrace their own culture. We see the movements of modern Korean or modern Indian, and it’s being celebrated. I think the Chinese context is a little more tricky, because you’ve got international migrants coming into New Zealand, and they’re bringing in really regional specific cuisine and no one’s really demanding or asking for a new type of Chinese food. In America, because there are established Chinatowns, and the population of Chinese people is so much larger, I think there are more peers who share a collective idea of modern Chinese cuisine and want to uplift and encourage. Whereas here, I’d find it difficult to name Chinese chefs in Western restaurants.

I read somewhere on the chefs that inspired you – Gordon Ramsay, Fuschia Dunlop, David Chang. What do you think it means that none of them are Chinese?

I think I can add one to that list! Brandon Jew in San Francisco. It is inspiring to see what he was doing, and learning that how he sees Chinese cuisine is exactly how I see it. It’s about preserving tradition and culture, but it is evolving it to a context that is more sustainable.

Sustainable?

Sustainable in a way that those traditions are morphed to fit us in our current context of living. So the type of ingredients used are more available to us, how it’s celebrated is more true to how it should be done in the environment that we’re based in. On New Year’s Day, for example, we would eat dried abalone and oysters with sea moss and dried bean curd – but you could morph that easily and use locally sourced ingredients.

What was the thought process behind the more generic naming of the dishes – for example, spicy saucy tofu instead of mapo tofu?

If I grew champagne grapes somewhere besides Champagne [France], you can’t call it champagne. I’m naming the ingredients and I’m naming where the source of inspiration is from, but the ingredients that we source here aren’t the same as Sichuan. For me to call it mapo tofu and compare it to the original would be unfair for me to say. I was careful about what I named it.

I think there’s definitely people that are very passionate gatekeepers of traditional cuisine. But with a mindset of cultural fluidity, when you’re outside of the source of the region, you really can’t gatekeep that anymore. That’s how I’ve been approaching it. It’s not so much about being worried about pissing people off; I just felt like it wasn’t right to call it something that has a traditional name.

And why did you choose to include personal essays, on how your queerness affects the way you see food, and the growing understanding of your own Chineseness?

I think the road to discovery of my own queerness and Chineseness is quite central to understanding how I think about the way I form my craft. By writing these down, and researching about queer food history and how Chineseness exists on a spectrum, you tend to formulate your own ideas of how you came to be as a person functioning in society.

Do you feel more Chinese?

I feel I’m more connected to my idea of what it means to be Chinese outside of China. Brandon [Jew] said he went to Shanghai to work under a famous chef and very quickly he realised he’s not Chinese, he’s Chinese-American. For me, it’s very much that. I’m Chinese-Kiwi-Fijian and I need to own that narrative. One thing that Nathan Joe said that speaks volumes is that people find relatability with very specific nuanced experiences. By being so specific by the way that I’ve formed my own identity, people can relate to that in their own context. The way it’s still celebrated – that’s a big goal of mine, to encourage people to think about their own influences that make them their own individual person.

The book spans across different types of regional cuisine – why did you design it that way?

The anchor of the book is Cantonese dominant food because those were the first types of Chinese food that reached the rest of the world. But with the growth of regional cuisine like Shanghainese and Sichuanese food, it was important for me to create entry-level recipes of dishes that represent those regions. And for people to understand the complexity of Chinese cuisine.

I’ve been reading The Food of China which delves into why the culinary scope is so large – it has one of the most contrasting climates in the world, from desserts to subtropical environments, and incredible flora and fauna diversity in one region. That alone speaks to its types of produce that could be created in those environments, let alone the neighbouring countries. When you have that type of influence and diversity, it’s hard to understand.

And has engaging, I guess, with your “Chineseness” in this way brought you closer to your parents

Yeah, me celebrating Chinese culture in general has made me closer to my parents. With them being part of the “Silence Generation” (a generation of people that have been brought up in a specific culture and environment, then moving away but still trying to uphold those values and way of thinking in a new environment which doesn’t serve them anymore), it’s sometimes hard to hold onto that purpose – but me highlighting Chinese culture with my parents means they’re able to relive parts of that purpose.

How does your use of social media affect the way you go about approaching other projects, like this cookbook?

I’ve been reading this book about the psychology of how we consume food media now and why there’s been such a rise in food content on Instagram and TikTok. It’s a very specific aesthetic that’s usually considered low quality content. But I find it to be the truest form of representing yourself, being on social media. That’s why there’s been this giant rise and fall of perfect food being presented online, because people just can’t find relatability in that type of cuisine.

This form of content allows for room for error – and room for people to create the final product better than the creator themselves. I’ve approached the book in the same manner. I didn’t want the food to be over garnished or too curated. I specifically made it slightly imperfect.

Finally – did writing this make you want to write more?

It took me over a year to write this book, and by the time I’d finished, I’d already had so many more ideas. So…

Modern Chinese is out next week, on October 3. Scroll up to learn how you can win a signed copy.

Redux

Four years ago, I lied to the world.

At the end of an essay titled ‘Does not knowing how to use chopsticks make you any less Asian?’ I said, “My fingers moved the chopsticks the way they’re meant to, without crossing over, picking up the last of the grains.” My fingers, when holding chopsticks, have never, in fact, moved the way they’re meant to – they move clumsy and slow, like when you have a nightmare about running away from someone chasing you but the air is thick and muddy and your feet keep slipping underneath you. Plus, I lack the discipline it takes to undo years of wrong behaviour. I picked the last clumps of rice in my bowl up with my misbehaving fingers – sans chopsticks – then, and I still do that now. I was just trying to make the story follow some sort of narrative arc and look successful.

I am one of the unlucky set of writers who grew up playing Neopets and reblogging GIF sets of Sherlock and have titanic digital footprints to sift through which represent their inner conflicts at every point of their formative years. Unluckily for me, my early-twenties are marked by years and years of articles and personal essays on metromagazine.co.nz, letting the wider public in as I try to write myself out of confused identity crises, when I felt deeply insecure about how my race and culture intersected with the legacy of Metro and writing in Aotearoa in general, when I felt strongly that I needed to Make Some Moves. Did I Make Some Moves? I don’t know! But the chopsticks essay is my favourite example of this era. It’s such a capsule of that time.

Here is a (much shortened) alternative universe version of that essay.

—

We ate dinner around the table every night, the six of us spread out across a long wooden oval. It’d be one of our jobs to set it: placemats with a flowery white-and-blue pattern swirled onto them, generically Chinese-looking, sticky and vinyl, a fork and a spoon set on either side. Fork on the left. Spoon on the right. Sometimes, Shortland St would be on, and we’d slurp soup as Joey strangled Ferndale residents; other times, we’d eat in silence, leaning forward to nab another portion of chicken or scoop soft flesh off the whole fish from sharing dishes plonked in the middle. It was there, at that dining table, that I learned how to eat: liberally, second helping of rice encouraged, with the flavours of soy sauce and ginger, of spring onion and chilli, licked off the end of my utensil.

Chopsticks, in comparison, were alien. They were harder to use, so I never used them – simple as that. My beef with them was one of a practical manner; it seemed only logical to ask for a fork and a spoon (“匙羹叉”), which usually arrived with no fuss. It was only later, when I got older and my sense of self was so fragile that I started to write into magazines complaining about their coverage of Asian food, that a self-consciousness creeped in – a marker of otherness in an environment where my otherness was supposed to be not an otherness at all. I felt weird about it.

Food was a cornerstone for how I expressed being Chinese; I used my cultural knowledge of how to order at yum cha and eat Peking duck and ask for more tea to prove my mettle in that world. Not being able to use chopsticks, then, made it all feel a bit fraud-like; as if I was Elizabeth Holmes, standing in front of her board, pleading that, yes, she was still capable of leading the company, and that everything was fine. Please continue to believe in me.

Here is what happens when I try to use chopsticks. My body slides into a different dimension, where the brain refuses to let new information in. The chopsticks rest awkwardly between my knuckles, and they feel wrong, like a strange appendage that you instinctively know shouldn’t be anywhere near you. They slip, and then cross over on the top, and keep crossing, no matter how much your dad says, “It’s easy, lah, just look at the way I do it. Perfectly, see.” They do the job, and they pick the noodles up – but it’s like wearing four-inch high heels to walk a marathon.

It’s stupid that I cared about this as much as I did. But while outwardly benign, how you eat is reflective of your upbringing and environment: the ease in which you do it; the etiquette slightly different depending on where you come from. It’s why it struck a nerve – this small, shallow characteristic that poked a tiny hole in how I conceived of my Chineseness and affected the way I performed it. It’s the everydayness of it; the reminder every time I try to pick something up on the lazy susan and it slips through, again and again, till I poke it with the end of a stick.

Wikipedia writes that, “In chopstick-using cultures, learning to use chopsticks is part of a child’s development process. The right way to use chopsticks is usually taught within the family.” Now, I see the problem for what it is: not a failure on the part of being Chinese, but a failure of my parents.

Four years later, I’ve learned that this part of me does not need to be massaged and triaged and made into content for others. Its value is in contributing to the lens I use to see the world, and that is much more interesting.

Goodbye!