Aug 5, 2017 Restaurants

Owners Ricky Lee and Makoto Tokuyama met in 2008, when Lee bought Soto (now Mary’s) in St Marys Bay, where Tokuyama was head chef.

Cocoro means “heart” in Japanese. At Cocoro, the contemporary Japanese restaurant, it ties into the concept of “ichi-go ichi-e”, a favourite idiom for Tokuyama that means “one opportunity, one encounter” and suggests that each moment should be treasured because it will never be repeated. This concept also defines my experience of a week spent with these people at this restaurant. It feels to me that, like many of the driven, dedicated personalities who have shaped Auckland’s restaurant landscape, Lee and Tokuyama embody the meaning

of hospitality.

Monday

It’s very early morning and Lee and Tokuyama are driving north to Leigh to visit a supplier. It’s their day off.

Lee Fish supplies Cocoro with high-quality line-caught fish. Sam Birch, Lee Fish’s sales and marketing manager, grew up in the area. His dad caught snapper for the company in the golden days when Lee Fish first found success exporting to Japan in the 70s and 80s — hence the name-change from Leigh to Lee. With that market these days favouring Japanese-sourced fish, it’s Birch’s job to grow new arms of the business. He began working for the company in the US seven years ago, but for the past three and a bit years, he’s been back in New Zealand.

Lee and Tokuyama put on protective hairnets, booties and ponchos and follow Birch into the sorting area. There’s a cacophony of crashes and bangs as men in white gumboots sort fish into bins that are then sealed and labelled, ready for export. Each box displays the species of fish, the grade, the date and time of the catch, and the name of the skipper who caught it. Today’s boxes are all on their way to Whole Foods Market in the US, but Tokuyama singles out one gleaming blue mackerel and it’s reserved for delivery to Cocoro the following day. Part of the service Lee Fish offers to around 200 restaurants nationwide is a mixed box — multiple species of fish in one bin. The process relies on skilled graders, men like Rex Dryland, who was a Lee Fish fisherman for 15 years and now works shifts on the sorting floor, keeping an eye out for the very best fish for high-end restaurant customers.

It’s thanks to the company’s history of fishing for the Japanese market that Lee Fish produces seafood of such high quality. It taught the fishermen of Leigh the “ikejime” method of killing fish, a humane, swift spike to the brain that “sounds mean but kills [the fish] instantly”, says Birch. It causes blood to retreat to the gut cavity of the fish, leaving the flesh clean and perfect for sashimi, without the metallic flavour or aroma that fish often develops as it ages.

When Birch returned to New Zealand, Cocoro was his first port of call. “I asked myself, ‘Where’s the best Japanese restaurant in New Zealand?’ Straight away I went to Cocoro. I saw Makoto on the street outside the restaurant and I said, ‘I’m from Lee Fish, we’re ikejime-ing our fish.’ And he was like, ‘Really…?’ He explained that he preferred to pick the fish out himself, but I said, ‘Look, just give me one chance…’”

For Cocoro’s first four years, Tokuyama would begin each day driving between three fish markets in Auckland. “Seriously, how many hours I spent every morning, just to find fish.” He looks at Birch: “He changed a lot, a huge amount. After he came back, straight away I really trusted him.”

Lee and Tokuyama leave the fishery just after sunrise, taking the winding road that leads to Te Arai Point. It’s time for surfing, the first real sign that this is not a work day. Tokuyama first learned to surf when he was 19 and living in Miyazaki, on the coast of Kyushu, Japan, and he’s never stopped. Being in the water is his main source of relaxation, and when he can’t make the time to surf, he takes his kids to the pools in Newmarket.

“This is my favourite place,” he says, overlooking the dunes and the broad crescent of golden sand that stretches up to Mangawhai. “My kids always complain about the long drive, but they love to play in the rock pools.” There is an abundance of edible life around the point — sea asparagus (samphire) and sea banana, seaweed and kina. Tokuyama began to teach himself about foraging in New Zealand 10 years ago. When he first arrived in the country on a working-holiday visa, he didn’t know anything about our wild foods, but foraging was a staple of his childhood in Japan, and it’s big part of his identity as a chef.

Tokuyama pulls a long board from the back of his car, zips up his wetsuit and disappears into the foaming waves. For him, this is the beginning of his week, the last moment of respite before the rush of routine begins again — collecting his kids from school, taking them to karate class, making sushi with his family on a Monday evening. He will still make time to collect kina when the tide goes out, before he heads home. “There is no such thing as a day off from Cocoro,” says Lee, and Tokuyama agrees: “If you think of it as work, I recommend you don’t become a chef.”

Tuesday

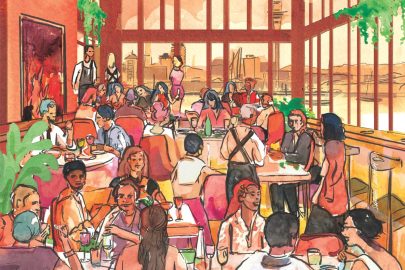

Cocoro’s dining room gets gentle, late-morning sun that streams in come lunchtime, softening to a cosy, almost theatrical glow at dusk. The restaurant is open five days a week for lunch and dinner and is rarely empty. Double shifts are all the team know.

The chefs arrive first in the morning, starting lunch prep from 9am. From 10am, Ricky Lee, as restaurant manager, can generally be found, laptop open, at the central table, with a coffee from the cafe next door beside him. The end of the financial year is approaching, and he’s in the process of running a stocktake on the extensive, award-winning wine list. Cocoro’s cellar is in a cupboard with a ceiling that gets lower the further back you go. To reach the most precious wine, Lee must get down on his hands and knees and crawl to the back of the space, where dusty bottles sit in racks, handwritten labels dangling from their necks.

Florist Kae Dale arrives to deliver her weekly centrepiece of flowers. She’s been arranging flowers for Lee and Tokuyama for at least 10 years, since their Soto days. She swaps a shallow bowl of white lisianthus and decorative persimmons for a tall, graceful vase filled with lotus-seed pods and a gentle explosion of pale-green hydrangeas. Cocoro’s interior is simple — dark wallpaper and parallel lines of polished wood running the length of the low ceiling. The flowers give a burst of colour, a softening effect.

After lunch service, one of the front-of-house staff takes a nap on a banquette beneath a dark blanket. She is barely visible. Very occasionally, if time allows, Tokuyama can also be spotted snatching a micro-sleep. He sets his alarm for three minutes. There’s no time for a nap today, though. He has a long conversation with one of the reps from Tokyo Food, a supplier that brings in specialty ingredients from Japan, including a sake from Tokuyama’s home town. Cocoro is the only restaurant in New Zealand in which you will find it.

Tonight, a regular customer has booked in for a special menu. It’s a family, based in Tahiti, who always visit Cocoro when in Auckland. Tonight, Tokuyama is making the restaurant’s signature sashimi platter, for them. It takes 45 minutes to plate, and only Tokuyama can do it, labouring over the placement of each sashimi slice, garnish and decorative element with a level of focus that feels meditative. Before service begins, Lee approaches Tokuyama’s station in the far corner of the kitchen to see how the dish is taking shape. There are more than 30 species of fish on the platter, far too many to remember by heart, so Lee uses an iPad to record them. He works quietly, only asking for confirmation every now and then. “It’s like a quiz every day,” he laughs, and points: “Tuna, alfonsino, trevally, John Dory, kingfish, red snapper, blue eye, kingfish…” The list goes on.

The first customers are half an hour late, but it’s not a problem as tonight is quiet. During services like these, Tokuyama tests dishes and plans new menus. He’s adding a lamb dish to the dégustation menu later in the week, and tonight wants to perfect it.

The final customer leaves at 10pm. The team have a stand-up staff meal in the kitchen before heading home. Tokuyama stretches and meditates each night before bed. If he has time and energy, he tries to read or study. “Reading is exercise for the brain,” he says.

Wednesday

For Tokuyama, every workday begins in the narrow wedge of morning sunlight that fills the small garden at his Avondale home. “It looks not maintained, but for me it’s maintained well,” he laughs. Today he is collecting three types of shiso, myoga (Japanese ginger), begonia flowers, pineapple sage, chrysanthemum, and Japanese mint that tastes just like toothpaste. Tokuyama keeps the garden in pots because he likes to be able to move everything around. Sometimes the spot is not quite right for the plant, and some plants can affect the flavour of others. He’s noticed that planting shiso next to mint gives the shiso a distinctly minty flavour that he does not want.

Having the garden at home is important because it helps Tokuyama to understand the quality of the produce and to become attuned to the seasons. He could get most of these ingredients from a supplier, but this way he knows the day something goes out of season. This morning, the garden is dotted with stainless-steel bowls that gradually fill with leaves, flowers and tubers. When he’s finished foraging, Tokuyama puts each bowl on the back step of the house, beside his jandals, before loading them into the car next to the cool box. Three surfboards hang on the wall of the carport above an old motorbike. He’s owned 10 motorbikes in his life, but this one was his first. He doesn’t ride anymore, but he’s keeping it for his children, in case they ever want to learn.

Tokuyama lived in a Zen Buddhist temple in Japan until he was 18. He is just one “test” away from being a recognised Zen Buddhist monk, and he would like to complete his training someday, as a way of giving thanks to his father — his fingertips rest lightly on his heart as he explains. Tokuyama’s father was a monk. He pushed for Makoto to follow the same path, but when his older brother got there first, his father reduced the pressure. Instead, Tokuyama spent eight years backpacking around Europe and Asia, and became a chef. “I think about my father and I think, his whole life, he never did anything for himself; that’s hospitality, to me.”

Lee’s morning begins with a visit to Newmarket’s Maison Vauron , with its vast attic-like store of French wine, where he picks up a couple of bottles. The team there have been very helpful since Cocoro’s maître d’ and sommelier of 10 years, Hiro Kawahara, left at the end of last year. The stocktake has also been a useful process to help Lee learn more about the complex list he’s inherited. For five years, Lee was able to step back from service, simply running the financial side of the restaurant. Now that he’s back managing front of house, he thinks it’s time to learn everything.

At the restaurant, Lee checks the bookings for the day. Cocoro’s customers reflect its standing in the hospitality community. When Clooney’s new chef, Jacob Kear, touched down in Auckland for the first time, he came straight to Cocoro to ask for advice about suppliers. Tonight, Chris Rupe, co-owner of SPQR and Augustus Bistro, is coming in for dinner with his family; Nadia Lim made a booking just yesterday. A few weeks ago, Pete Evans and Manu Feildel of My Kitchen Rules came in, separately, on nights off from filming their show. Feildel raved via Instagram that Cocoro was one of the best Japanese restaurants he’d ever been to, prompting new customers to visit.

Today, the memory of that positive social media moment is overshadowed by one that is less so. Early in the day, a young media personality calls to make a booking for dinner that evening, requesting the sashimi platter. As the kitchen needs 24 hours’ notice to produce the dish, Lee apologises, explaining that the à la carte menu will be available, but he is unable to offer the platter. As a result, the woman chooses not to book, and goes straight to restaurant review site Zomato to complain about the experience. This upsets Lee. After more than a decade in the industry, he is not afraid of bad feedback, provided the diner has actually come to the restaurant. He’s concerned about the size of her online following, but also frustrated about the difficulties of communicating the booking requirements at Cocoro over the phone, particularly to new customers. He asks Zomato to take the review down because she hasn’t been to the restaurant, and they agree to do so. He is relieved. This is his primary memory of the day: the ups and downs of social media.

Thursday

The days of going to multiple fish markets may be over, but Tokuyama still has plenty of stops to make each morning before arriving at the restaurant. Today, he begins at the Westmere Butchery, where he picks up an extra-large chicken, because no supplier will deliver him the size he wants. Owner Dave Rossiter organises a special order. “I am that annoying chef,” Tokuyama shrugs, laughing.

Next stop is New World Victoria Park for odds and ends. He buys two packets of raspberries and three ripe bananas, after spending a few minutes picking and choosing. “Suppliers deliver me green or yellow; they don’t care,” he says. “So I like to pick them myself.” On the way past the fridge, he buys a protein drink. “This is my secret.” He eats during the day only if he has time, and generally finds that the stress of hunger is not as bad as the stress of being full and sluggish.

The final stop before the restaurant is “Smelly Alley”, the narrow street of Chinese produce shops behind Broadway in Newmarket. Tokuyama is well known there, so much so that customers often try to speak to him in Mandarin, thinking he’s an employee. He enters through the loading dock to see the latest deliveries. There is a large, glistening salmon, and three massive hapuku with mouths gaping like grotesque cartoon characters.

The fish Tokuyama buys here supplement his orders from Lee Fish. He spends a long time choosing, hands amongst the ice and slush. He’s looking for thick fleshiness along the ridge of the fish. Sometimes, he smells beneath the gills because it often gives away what the fish has been eating. Today, he handles two blue mackerel and can tell the flesh beneath the skin of one is broken already — it’s no good for sashimi. He chooses a John Dory and two blue mackerel. While he’s there, four chefs from other Japanese restaurants in town arrive. He knows them all.

At the vegetable shop, too, Tokuyama bypasses the front door, walking straight into storage rooms and coolers, looking for quality produce. Sometimes he comes here just to pick up one zucchini — if it’s good. The daikon here is often better quality than what he can get from a supplier. Today, he buys a head of celery, scribbling the words ‘cocoro’ and ‘celery’ on a note which he pushes onto a spike, walking out the door without a word to anyone.

Back at the restaurant, it’s a busy day for Ricky Lee because a couple of supplier orders haven’t arrived. He has to make a trip to the market before lunch service to buy a whole salmon. He stops at the supermarket for four bags of ice as the restaurant is running low — and it needs a lot for sashimi.

One dish on the dégustation menu is changing from chicken to lamb today, so, while Tokuyama is doing a final test and plating it, Lee tests the wine and sake matches. Then he works out a description for the dish, prints new menus, and briefs the front-of-house team.

Both lunch and dinner are busy, although two groups don’t show up for their tables. Lee had confirmed by phone with one group in the afternoon, and the other booked at 5pm for a 9pm dinner, but neither arrives or calls.

After service, there is ordering to be done to cover the next two days of trading as most suppliers don’t deliver over the weekend. There is sake to order from Tokyo Food and Antipodes water from Negociants. Lee is also looking for a replacement chardonnay for his list. He speaks to Blair Walters at Felton Road, who agrees to send 24 bottles of his library stock of Elms 2013.

It’s been a long, tiring day and the weekend rush is only just beginning. Lee drives the front-of-house staff home. In Avondale, Tokuyama stretches, meditates and goes to bed.

Friday

Lunch bookings don’t look too busy today, and Lee is hoping to sneak out to see his youngest daughter at a special school assembly at which her class is performing. Unfortunately, a staff member calls in sick, which rules that out. Later, Lee is heartened when a long-time customer rings just before lunch to make a booking. He lives out of Auckland these days so they don’t see much of him. Two more groups of regular customers come in for lunch, too. Cocoro’s lunch services are often filled with regulars; these are the people who have kept the restaurant going over the years. Seeing familiar faces balances Lee’s disappointment at missing his daughter’s performance.

There is no time for a nap before Friday evening’s service because Tokuyama needs to create four sashimi platters for 11 people in a tight timeframe. One family of five are new customers, who are very excited because they’ve seen the dish on social media. They wait patiently for their platter, and when it arrives, they take a few, cautious bites and then ask if they can take it away. Lee checks in that everything is okay, and they tell him the dish is too fresh, too cold, too raw. They would like him to ask if the chef can cook it instead. Lee goes with the first option, asking the kitchen to prepare the platter to take away, and doesn’t have the heart to tell Tokuyama until the following day. He imagines that carefully constructed platter becoming “sashimi fried rice” at home, and puts his head in his hands, half laughing, half crying.

During the night, two tourists in Auckland for a couple of days come in for dinner on a friend’s recommendation. Lee gives them a few local tips, suggest-ing they visit Rad cafe in Mt Eden, Baduzzi on the waterfront, and Depot . The pair accidentally leave a scarf at the restaurant, and since Lee can recall what hotel they are staying at, he drops it at the front desk on his way home.

Saturday

Every Saturday after lunch, the kitchen makes the whole team noodles before the last service of the week. It gives them all the last rush of energy they need to get through. They are a close-knit bunch. Tokuyama’s sous chef, Shojiro Takasu, who has been working with him since Soto days, comes from the same small village in Japan. The front-of-house team turnover is higher, because the staff are generally here on working-holiday visas.

Lunch service is busy and passes in a blur, but dinner is quiet. At 10pm, there are just three tables left, and Lee is chatting to one pair whom he knows from the wine industry. All the tables are eating their dessert and the kitchen is shifting gear as they begin to clean down. Tokuyama is always the first to start and the last to finish everything, including the cleaning.

As the final customers leave, they approach Lee to say things like, “That was so good, thank you,” and, “We’ll be back.” The front-of-house staff are polishing cutlery and glassware and stacking it neatly on the central table. As each section empties, the linen is quietly removed and the tables reset for Tuesday lunch. A vacuum cleaner is tucked beneath a table in anticipation.

When the final customer walks out the door, everyone springs into action. Large bags of linen are hauled out to Lee’s car — they will be taken to the cleaners on Monday morning. The pot plants in the windowless, temple-like bathroom are moved to their nightly spot by the door so they can soak up the morning rays of sunlight.

In the kitchen, the staff meal is being prepared. It’s an assortment of leftovers and snacks: a whole plate of sashimi arranged in a flower pattern, nigiri, sushi, noodles, greens in a fish stock broth. There are also rice crackers with delicious cubes of cream cheese that have been aged in miso.

Lee cashes up the till, plugging the day’s turnover into an immaculate, detailed spreadsheet that he’s been using for more than 10 years. He separates the receipts by credit card and staples them together. “It’s just a habit. Makoto has a thing he says, ‘It’s all simple stuff that you just keep on doing.’ We think it’s normal, the things we do every day, but I guess it adds up and makes us different.

I never think we do anything special.”

In the kitchen, the staff are eating octopus sashimi with finely sliced myoga from Tokuyama’s garden. They drink leftover wine and ice-cold bottles of beer. Chairs have been pulled up, but most remain standing. “Do you know why we don’t eat there [the dining room]?” someone asks. “Because if we sit down, we drink too much. We never get up, we just keep on going!” They all laugh.

“Are you surfing tomorrow?” Lee asks Tokuyama. “Yes,” he replies, and then gives a shout of laughter when Lee opens a bottle of premium sake. “I am still going,” he says, sipping the sake. Will he be tired? “Sometimes I get tired, sometimes my heart gets tired, but this is not work, this is life. That’s why I love it.”

This is published in the May – June 2017 issue of Metro.

Get Metro delivered to your inbox

/MetromagnzL @Metromagnz @Metromagnz