Dec 18, 2019 Restaurants

When you’d like some care and attention, degustation dining can feel like sitting through a lecture.

?Read Metro food writer Jean Teng’s argument for degustation here.

Is it thanks to the advent of the modernist gastronomy celebrity chef? First Ferran Adrià, then René Redzepi, along with many others. Restaurants booked out for months ahead; moody Chef’s Table interviews about failure and triumph; documentaries with the chef foraging wild herbs from the banks of a local river. Large, heavy books with intense photography and recipes you’ll never cook.

The idea of the chef as intellectual and artist, the meal they make you a journey through memory and geography, to be absorbed in a multitude of tiny little courses, rather than three or four. In their hands, the things on your plate became a culinary novel, a narrative constructed around their ego, their place in the world, and the ingredients they have to hand.

The word “degustation” emerged in France in the early 20th century — a deliberate counterpoint to standard old three-course dinner, and by the 1980s and 1990s in France it was the height of fashion — helped, perhaps, by the popularity of the small, punchy courses of nouvelle cuisine. It spread to Auckland sometime in the mid-2000s and by the beginning of this year, eating in most of our fine-dining restaurants for Restaurant of the Year, I realised that almost none of them offer a menu any more, or more particularly, they only offer you one.

On one level, as restaurants around Auckland, from the late Merediths to Sidart , switched to degustation, I welcomed it. Sometimes it’s exciting, sometimes it’s thrilling. Apart from anything else, the entrees and appetisers are always more interesting than the main, right? And thankfully, a degustation is a particularly elegant way around tackling the lump of medium-rare protein with clever sauces that so often seems to appear on the mains in nice restaurants. Instead of a huge piece of protein, they just feed you lots of smallish portions, like a goose being fattened up for the harvesting of its liver.

But, more recently, I’ve started to tire of the whole bloody thing. I love the idea of fireworks on the plate. I love the idea of a series of small courses that tell a story. I don’t even mind paying for it — given that even some very ordinary restaurants in Auckland now charge more than $40 for a main, $180 for nine courses seems like pretty good going to me, though I’m not sure whether 23-year-old me would be able to save up to eat out in these restaurants the way I did in the early 2000s, and that bothers me.

I understand also that, their culinary story aside, one of the big reasons to shift to this model is to reduce waste — if you have to keep several servings of the wagyu fillet in the fridge, inevitably some of it will go to waste. That’s bad for the planet, and it costs you money.

But my chief objection isn’t about the food, or the price, or even about how many courses there are, and how most of the time I go home after eating and lie on the couch and groan with how much food I’ve just consumed, or how they always say the wine matching is only small glasses but always feels like the better part of a bottle even though it’s only Tuesday night, or the fact that these restaurants are now frequently inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t eat everything because they can’t cope with dietary changes. (Once, my then-pregnant wife was served four green olives in a bowl in place of a mozzarella course, and five roasted almonds instead of the clams, as part of a meal we had paid $150 for.)

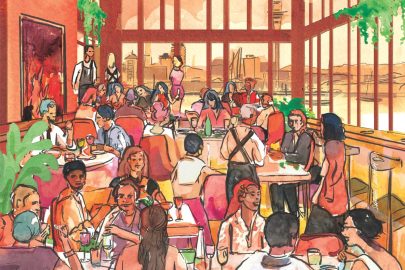

No. My chief objection is that it is mostly really, really, boring. There’s a theatre to eating out — that’s why we go. Food is only part of the equation. We go to be cosseted, to be looked after, to see other people and to be seen. You might not like to admit it, but we also go to talk to strangers who pretend to be your friends in a particular social context in which you are acting a part as much as the waiter and you both know it. Good waiters are actors on a stage, and the best ones make you part of the act.

Remember when you used to go to a fine-dining restaurant and you were greeted at the door and treated carefully and kindly, and they actually talked to you about how you were, and what was going on. They explained the menu, that they had Bluff oysters in today, or mozzarella from Clevedon. And they helped you construct a menu that would work, and you could say things like, “Should I have the venison or the duck?”, and then there was a whole conversation to be had about wine and you just generally felt like they gave a shit?

Somehow, in switching to multi-course menus with wine matching, fine-dining restaurants have forgotten that they need to talk to you. They’ve changed the fine balance, the see-saw rhythm of restaurant experience. It’s almost entirely not about you, and it’s almost entirely all about them. It’s stopped being about what you want to eat and how you feel that day, and whether they can help you with that, and it’s started being about how much they can tell you about the chef’s childhood.

Instead of getting to know you, their waiters have become automatons, and the role of the waiter as a social enabler has been relegated to much more casual restaurants. Is it any wonder Mo Koski, one of Auckland’s best waiters, now runs a casual wine bar after a career spent as a wine waiter in fine-dining restaurants? He’s an actor, a talker, a man adept at reading a crowd, and he dances around that bar with balletic grace, up and down from table to table, getting down on your level. You can’t do that when the wine order’s been decided six weeks before, along with the new spring menu.

I’ve eaten in almost all of Auckland’s fine-dining restaurants this year, and in almost every case, no one has asked me more than three questions: Do you have any dietary requirements? What number of courses are you doing? And are you doing the wine matching? And then they just bring you the food, and the wine, and give you a rote speech about what you’re going to eat and drink, before flouncing off. In one case, I watched a German couple sit and struggle with a dish inspired by curry that was way too hot for them, before giving up. In another restaurant, a waiter bored me to tears with long-winded, overtly political discussions of provenance. In another, I cracked jokes, and he didn’t laugh, but carried on with his serious little chat.

The result is a dining experience that has subtly shifted from theatre to lecture. The staff don’t have to get to know you, so they don’t. And then they charge you the most amount of money you will pay for dinner in Auckland.

It doesn’t have to be like this, of course, and it isn’t, not always. In April, judging Restaurant of the Year, I sat up at the bar at Pasture with our guest judge Pat Nourse, entirely transfixed as the chefs danced around each other preparing some of the most sublime food I’ve eaten in a long time, while the music played loudly and the six patrons felt like they were sitting in a bar. We talked to each other, and we talked to our dining partners and we talked to head chef and owner Ed Verner about natural wine and AC/DC and where the wagyu cow we were eating came from. It was generally, remarkably, fantastic, like a private party in front of an open fire in the kitchen of an amazing chef with a liking for 1980s power ballads.

And many years ago, I remember eating at Loam, a restaurant a couple of hours from Melbourne that didn’t last long. I was with a food-obsessed friend who had booked us in months before. I flew in and we drove out and had lunch, sitting beside the window looking out over rolling olive-green country that sat below a flat silver sky. The waiter was brilliant: he’d worked in Melbourne for years before moving to the country for a quieter life. He asked us questions, which slowly developed into what we liked and didn’t like, and what you’d been doing that day. It was a kind of interview process and then he went away and made us a menu based on what was good that day. We ate and drank different things, all of it stripped back and wondrous — I remember a dish that was barely more than a witloof leaf, with drops of balsamic and olive oil — and then, as we left, were presented with a menu to take away. I just wish more Auckland restaurateurs could have had the chance to visit.

This piece originally appeared in the November-December 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline ‘No dego’.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to our weekly email