Dec 22, 2016 Restaurants

“Good steaks. Everything else appalling,” fumed Warwick Roger in a review of Tony’s restaurant in the July 1985 issue of Metro. “Try it at your own risk. Personally I would never bother again.”

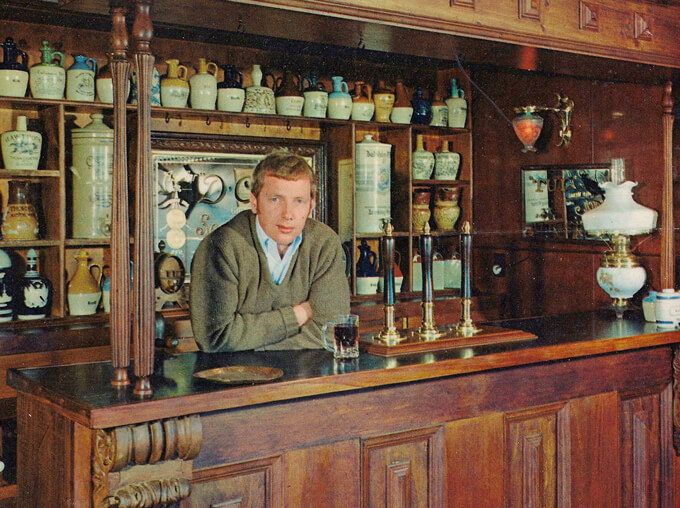

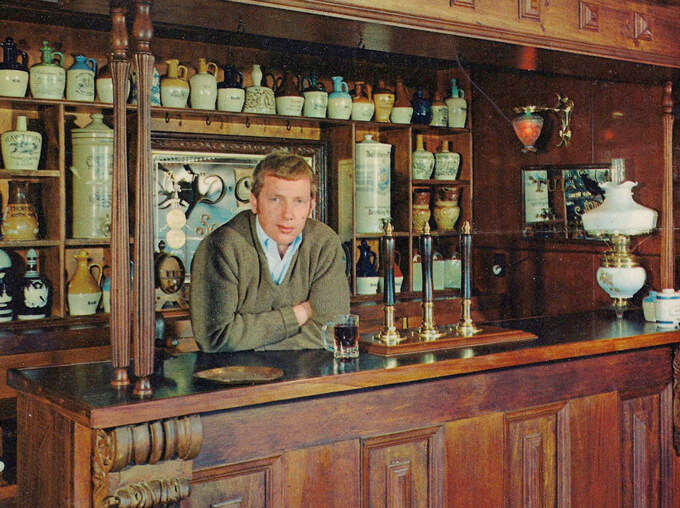

Tony’s quickly became a destination — at a time when there was bugger all else to measure the quality of your dining experience against, it was a benchmark for eating out. The atmosphere was jovial. The restaurant was a magnet for businessmen, actors and celebrities, one of whom once had a bowl of spaghetti tipped over his head for complaining about the food.

Artist Judy Millar spent much of the late 70s working for “social renegade” White. “Tony drew around him an amazing cast of people. There were punks and uptight Christians working alongside the likes of John Banks and a librarian who moonlighted at Tony’s in order to buy Tony Fomison paintings. There was a strong sense of family created amongst a range of otherwise social misfits.”

In the chain’s heyday, there were seven Tony’s in Auckland. But by 1985, when Warwick Roger reviewed the original Wellesley St restaurant, the ambience was “dark and tacky”. (As for the service: “What was this? Fawlty Bloody Towers? Someone’s idea of a joke? Chemical use among the staff, leading to brain damage?”)

Three decades on, Tony’s Original Steak & Seafood Restaurant in Wellesley St and Tony’s Lord Nelson in Victoria St are still serving good steaks. But on Christmas Eve, Tony’s on Lorne Street takes its last orders.

“The council are parasites on the backs of hardworking restaurateurs! Write that down!” Damon Ropata is a bit pissed off about his restaurant’s imminent closure. He’s owned Tony’s on Lorne Street for 18 years, since buying it from Darcy Brighton and Tony’s brother, David White. (Tony White, who opened the Lorne St restaurant in 1968, died in 2011.) But after a rent hike, a surge of restaurant openings in the central city and spats with Auckland Council, Ropata is packing it in.

Like Ropata, Tony’s on Lorne Street is tired. The raw-steak-red wallpaper has faded, the stained-glass lights are dusty. The menu remains relatively unchanged — you can still order steak with peppercorn sauce, spud and salad. There are no frills, no craft beer or farm-to-table policy here. Tony’s is in a timewarp.

In the tradition of its founder, Ropata is a sociable guy. He likes to linger for a chat with diners. He met his long-time partner, Renata Selva, at the restaurant. She started as a waitress and never left, seduced by his cameo appearances on the piano and his fun-loving nature. With Ropata around, long lunches turned into long nights of singing, with booze by the bucketload and new friends spilling out into what was then Khartoum Place as the sun started to rise. It may come as no surprise that Ropata insisted I drink a huge glass of red wine with my 11am breakfast steak.

Jason Van Dorsten, executive chef at Hanoi Kitchen, got his start at Tony’s as a dish hand. He has fond memories of drinking, gambling and watching people bathe in the fountain outside after kids had filled it with soap.

He lived upstairs and recalls waking up in the lift early one morning after a night drinking Illusions (the Midori-based cocktail), grabbing his whites and heading to work still reeking of booze.

Tony’s on Lorne Street still has its faithful regulars, though many are now pushing 80 and can’t get to town as often as they once did. Ropata blames strict drink-driving laws, expensive taxis and downtownparking fees for the drop-off in trade.

Tony’s decades of revelry have faded to a quiet hum. Ropata feels jaded and his feet hurt. It’s time to move on.

But first, there’s going to be one hell of a final party.

This article is published in the new issue of Metro, On sale now.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the weekly e-mail