Jun 3, 2016 Restaurants

Words by Alice Harbourne, photos by Ken Downie and Alice Harbourne. This article is published in the June 2016 issue of Metro.

Oaken

130 Quay St, central city.

oaken.co.nz

Hours: Mon-Fri: 7am-midnight, Saturday 8am-midnight, closed Sundays.

Dinner bill: small shared plates $10-$15, “one very special dish” $25, desserts $12

Successful all-day eateries are masters of mood. Staff shepherd day into night with ritualistic habit: the lighting of candles, the dimming of lights, the changing of aprons, the straightening of shoulders. The din of the smoothie blender is seamlessly replaced with the chitter-chatter and cutlery clatter

of a contented restaurant.

At Oaken, the transition happens at 3pm, when the inventive menu of deconstructed breakfast classics and perfumed lassies devised by executive chef Javier Carmona — yes, him, from Beirut and Mexico (the restaurants, not places) — taps out and is replaced by a menu of 12 “artisan dishes, good for sharing”, one “very special dish”, two desserts and dozens of interesting wines.

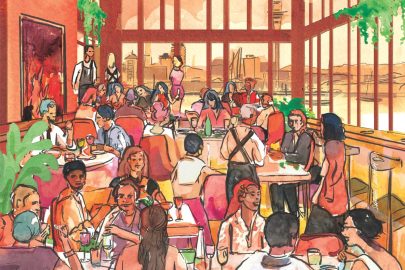

Come evening, the staff will tell you it’s not a restaurant, it’s a wine bar. If you find yourself sitting at the informal chef’s table by the open kitchen, your senses will tell you otherwise. So, too, will the restaurant’s — sorry, bar’s — main seating area, which suspiciously resembles a dining room, with low oak furniture, cosy nooks and communal tables, all designed by Nick McCaw and Nat Cheshire. It’s breezy and light by day, a dusky, sumptuous room to sit in at night. They clearly nailed the brief.

At Beirut, the smart Middle Eastern restaurant that Carmona opened late last year, we labelled his boundary-pushing dishes “studies in rapture”. At Oaken, he takes things one step further. Every dish centres on a hero artisanal ingredient, a bold flavour that is worshipped with counterfoils and innovative techniques. A delicate pile of shaved wagyu bresaola, for instance, is scattered with bitter parsley stalks and placed alongside four fermented watermelon rinds. They’re a substitute for sour pickles, competing with but never overpowering the rich veins of aged red meat. But then something utterly weird happens. The carefully matured, balanced flavours are doused with grassy extra virgin olive oil and mustard oil.

Mustard contains a colourless oil known as allyl isothiocyanate. It’s responsible for that nasal, have-I-been-poisoned-oh-no-it’s-fine sensation that in small doses reminds us to pay attention to the flavours of our food. At Oaken, it ruins almost half the dishes on the menu.

Uncontaminated, a delicate plate of thin cauliflower slivers, aged ricotta, honey and crunchy puffed farro would be subtle and beautiful. I held the dish up to the light, hoping the mustard oil would reveal itself so I could eat around it, but it’s sneaky.

If it wasn’t mustard oil that was being overused, it was smoke. Every small plate comes served with perfectly home-baked sourdough and a generous helping of manuka-ash-sprinkled, home-churned butter. By itself, comforting and caramelly, but eaten alongside the smoked mozzarella (also topped with ash, parsnip this time), and the daily special of eggplant stuffed with smoked yoghurt, hazelnut praline and tomato, and a dish featuring charred lettuce, it all left me a day later with a medieval aftertaste that no mouthwash could remove. Good luck, glass of beautifully round, dry I Favati Fiano.

Perhaps I needed to ask more questions. The service is welcoming, proud but not smug, and they know their extensive rotating wine list well. They seem to know the food even better, so I was a little surprised we weren’t steered away from ordering every smoky dish and every mustardy dish, or recommended a robust wine to stand up to the onslaught our sinuses were about to endure. If wine is intended to be the main event (which the prices suggest), the food needs to enhance its complexities, not mask them.

Go to Oaken on a Thursday. The “very special dish” that day is roast pork cheek, crackling on, with chewy, caramelised parsnip, the welcome neutrality of silverbeet, mint, pita and gravy. It’s slurpy, homely and most importantly, devoid of mustard oil. It’s also undeniably dinner, which Oaken should embrace. It’s got everything else a successful all-day restaurant needs: a chef willing to take risks, attentive staff, a prime location. Dishes would then have to be considered in the context of a rounded dining experience, rather than technically in isolation. Alternatively, suggest a few wine matches for each dish, serve ash-less butter, and stop pranking diners with mustard oil.

3 spoons.