Oct 11, 2019 Restaurants

Tony Stewart’s glamorous Freemans Bay restaurant always aimed high, but often fell short.

The last thing I ever ate at Clooney is the thing that will forever stand out in my mind as an emblem for the restaurant’s 13 years in business. It was 11pm on a Tuesday, the end of a three-hour degustation, and the final dish came out, described on the menu as “the mandarin”. I’d seen them coming out all evening, little bright orange balls, about a third bigger than a standard mandarin. It arrived on a grey stone-like plate, perfectly dimpled, with a real mandarin stem pressed gently into the top.

By the time you read this, Clooney, a glamorous fine-dining restaurant in Auckland’s Freemans Bay, will probably have closed, after 13 years in business [It closes on Sunday – Ed]. Owner Tony Stewart announced the news in August, via a press release and an exclusive interview with Jesse Mulligan in the New Zealand Herald’s Viva, in which he revealed he suffers from cystic fibrosis and is one of 52 people with the disease to survive past 50 in this country.

Mulligan detailed Stewart’s illness, and his desire to do other things and to spend more time with his family. He was effusive. “In current chef Nobu Lee, and before him, Jacob Kear, Tony lured two of the world’s great talents to a little back street in Auckland, and we were all the beneficiaries,” he wrote. “For 13 years, we are lucky to have had him behind the helm of such a game-changing restaurant.”

Clooney opened in 2006, in a former warehouse designed by Fearon Hay. I visited not long before it opened; I remember concrete dust and concrete saws and water, everywhere, though I’m not really sure why. Stewart led me around the restaurant, up the stairs to the toilets, showing me where the individual stalls would go. I knew him, vaguely, from his bar, Match, on Pitt St. He’d never owned a restaurant, but he wanted to change the game. He was keyed up, earnest, detail obsessed. He had a passion for wine, but by his own admission he knew very little about food.

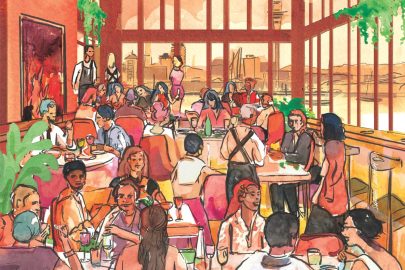

When the restaurant opened, it was something approaching extraordinary. Raw concrete walls, caramel leather banquettes, moody lighting, black mesh curtains pulled through the space to define different zones. It was rumoured to have cost $4 million — an enormous sum back then, the kind of international-level fitout that New Zealand had never seen. Sydney had come to Auckland, and we felt better for it. In 2006, remember, the best restaurant in Auckland was The French Café pre-expansion — a simple, elegant space where the interior design ran to a couple of lovely Karl Maughans.

A few months later, I judged Clooney’s first menu for Metro’s Restaurant of the Year 2007. The place was heaving with middle-aged men in striped shirts — it seemed like Clooney was really working as a place to drink, not a place to eat. It was noisy. Some of the food was great, much of it was not. There was a snapper with a bitter-sweet dressing that was too sweet, a chive gnocchi with scallops that was overwhelmed by its sauce. There was, though, an excellent dish of braised wild boar served with broccolini that was very tasty, despite having been braised, shredded, rolled and then roasted.

Such complications came to be a mark of Clooney, through various chefs, and it always seemed to be aiming for a place that was slightly beyond it, and its way of getting there was to add more and more tricks to the food, without ever quite nailing it. Going back through our Restaurant of the Year notes, I noticed the same things emerging: complicated food, glamorous room, great booze. “Needs to be funkier, less fussy, fuller tasting, and more integrated, too,” wrote one judge in 2008. “Does the chef really know what’s good? Almost every dish had something wrong.” In other years, the judges were ecstatic, and one year it won Best Fine Dining Restaurant, but to me, it just never seemed to fulfil its own promises.

In 2011 — infamously — the editor of Metro at the time, Simon Wilson, took the food writer A.A. Gill to Clooney and wrote about it. Wilson rang me a few days before to invite me to dinner: I said no initially, because I’d heard Gill was a bit of a pillock in person, which he duly turned out to be. I told Wilson to take him somewhere unpretentious, where he could get a steak. He hummed, and rang me back. “I’ve booked Clooney.” My heart sank. I knew Gill would hate it — and so, I’ve always suspected, did Wilson.

The evening was, indeed, painful. Gill ran outrageous lines that later turned up in columns, and the food was overwrought. One waiter’s hand shook with fear as he put down each plate, and Gill asked him what sex the “red deer” had been. They offered him a drink, several times, despite him being very publicly a teetotal alcoholic. He barely touched his food. By dessert — a chocolate soufflé with a syringe full of hot chocolate in it, and a deconstructed lemon meringue pie — Gill was clearly unimpressed. “All that effort and the best you can hope for is that it will taste like it should anyway. Why do they bother?”

Three years later, Clooney’s three backers — independently wealthy partners including Peter Huljich — sold the restaurant operation to Stewart, and the four put the various entities associated with it into liquidation. Shortly after, Inland Revenue went to the High Court to pursue Stewart’s restaurant entity for liquidation also. The August 2019 liquidators’ reports noted a sum of $383,959 still outstanding for each of the four associated companies. Stewart was personally listed as a creditor, along with the restaurant. “We are currently pursuing recovery actions,” the reports noted.

By 2017, Stewart had got back on his feet and hired Kear as chef. Kear was a Japanese-American who had worked for René Redzepi at Noma, fell in love with New Zealand on a holiday, and wrote to every restaurant here offering his services. Stewart spent $200,000 refitting the kitchen and announced an ambition for Clooney to be the first New Zealand eatery on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

Kear’s food was sublime, extraordinary, 13 courses of culinary theatrics: a green tomato and pine drink infused with Thai basil seeds, presented in a textured ceramic bowl; fresh storm clams from Cloudy Bay, served on a buttermilk sauce with slices of unripe strawberries and gooseberries; a dish of zebra-striped tomatoes, dehydrated tomatoes, dehydrated gooseberries, elderflower oil, red shiso flowers — and a green basil leaf pointing, apparently, in the direction of the wind when it was picked.

It didn’t last. Ten months in, Kear left in a blaze of bad publicity after a stoush in the kitchen. Stewart felt bruised, he said publicly; the relationship had gone septic. He was closing the restaurant, and would open again the following year with a more casual offering. “I feel like I’ve had the shit kicked out of me. I never want to go through this again with a chef,” Stewart told Stuff’s Jeremy Olds. “It’s absolutely heartbreaking.”

When the news of its final closure broke, I wasn’t surprised. It had always seemed like a restaurant that hadn’t quite got there, and that can’t have been very much fun for anyone. (Clearly, it wasn’t a recipe for a particularly successful business either.) Despite Stewart saying he was going to open a more casual offering, the Clooney that reopened in 2018 with Lee as chef was still a fine diner, with a multi-course degustation menu inspired by the history and taste of New Zealand.

I went there the other night, as a sort of goodbye to a restaurant I’d never really loved but had always respected for at least having ambition. And I’ve always liked Stewart’s gentle, earnest manner. In a way, I suppose, I’ve always felt a little sorry for him: the worry of pursuing that ambition over 13 years seems etched into his face.

The dining room was hushed. Couples sat side by side on the leather banquettes; a larger party dined over in the corner, discreetly shielded by curtains. We sat there for three hours, while a humourless waiter explained every last dish on the menu in excruciating detail, and announced things like, “We as a restaurant believe that the crayfish quota around New Zealand should be halved.” It was, to say the least, an uncomfortable experience — at $560 for two. I found myself wishing I was sitting up at the bar at Pasture, where the story around provenance and ingredients is similar, but where the music is loud and there’s a fire and you feel like you’re having fun while eating some extraordinary food.

There was “a tribute to Maori”, which riffed on the way Maori used to store mussels and just tasted like a pickled mussel on a crispy “shell”. There was salmon that had been brined, rolled and then slow-cooked, and I thought: 13 years on, and they’re still torturing protein. A cauliflower dish was bland, offset by a few pickled blueberries. The duck dish was a knockout, dried so the skin didn’t come away from the flesh, and then served rare with a tamarillo emulsion and a preserved radicchio — sweet and sour, gamey and fabulous. The beef was incredible: Ocean Beef tenderloin, pink and sumptuous, it had the texture of jelly and yielded to the gentlest slice of a knife. Desserts were finely wrought, delicately balanced — I loved a dish of rhubarb with yuzu ice cream, topped with a sugary black-tea disc.

Oh, and that “mandarin”? (It was listed as the final “canapé” — a parting shot, of sorts.) I chopped down into it, and the skin turned out to be a fine layer of white chocolate surrounding a mild mandarin mousse with a passionfruit interior. It looked spectacular. It had clearly taken many hours to put together, a thing I could never contemplate making myself. Was it better than a really good mandarin? Not quite.

This piece originally appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Clooney 2006-2019”.