Dec 15, 2022 Restaurants

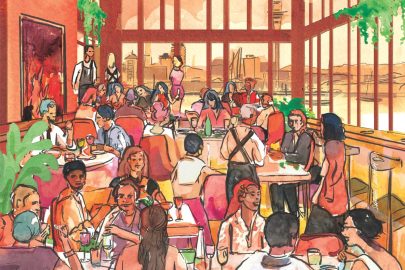

A woman has a coffee and a croissant at a cafe. She is by herself, staring out the window, chewing and drinking in silence. She could be enjoying her pastry and piccolo, leisurely people-watching in peace. Or she could be desperately refuelling, mindlessly consuming caffeine and carbohydrates before she has to return to the office. Sometimes eating out alone is a ritual, and sometimes eating out alone is routine. Life-preserving dinners, bland rest stops and everything in between — the lone diner is a multifaceted creature. I am one of them, and I have eaten alone with every emotion.

The first time I ate alone was during primary school at Wendy’s (the ice-cream one, not the burger one). I had a hot dog at one of the two plastic tables while my mum was shopping. The hot-dog bun had been stabbed on to a red-hot metal spike, toasting the inner void that would be lubricated in cheese and onion before the sausage’s entry, with a final saucing of ketchup and mustard. It was paper-wrapped satisfaction, as hot-dog forward meals usually are. Sitting down and eating melted cheese was much better than being dragged around The Warehouse. It was a perfect dining experience. Moments like this were rare — children don’t go to restaurants alone. To eat out by yourself, you need to pay for yourself.

While at architecture school in Wellington, I was paid to write for the first time ever. Not much, but enough for lunch. Every now and then I would take myself to a Japanese restaurant, Tatsushi, for a long lunch on a weekday. This was back at their original location on Victoria St, a cosy, wood-floored place with an open kitchen at its centre and tall windows. Whatever fragments of sun there were in Wellington would find their way through these panes. There were just a handful of tables that mostly sat two. It was an intimate set-up in New Zealand, where restaurants tend to not be so solo-friendly. By the window, I ordered agedashi tofu, a salmon chirashi bowl and an iced green tea. At the time, it was the ultimate indulgence. I loved the bistro-energy of the restaurant, I loved that it wasn’t Studylink or a family member who was paying for my meal, I loved how delicious the food was. There were often other people eating alone at the restaurant, and the other diners always seemed interesting, self-sufficient. Eating there felt like I was getting closer to becoming who I wanted to be.

Several years later, while working a demanding but rewarding job in Hong Kong, I took a day off to try a brand-new restaurant specialising in Korean temple food. It was on the top floor of a new mall that looked like what an AI image generator would produce if you asked for ‘bougie mall trying to be arty’. It was a weekday; I could enjoy the seven-course set lunch menu. Dish after dish of perfectly composed vegetarian happiness appeared at my table with almost too-good service. I had never eaten so many delicious unknown roots, rich and deep unseen shoots. Victoria Harbour glittered in the distance. Just like in Wellington, I savoured the food as much as I savoured the complete leisure of a long weekday lunch. The other diners were either suited people having business lunches or well-off mothers discussing boarding schools and babysitter dramas. I ate slowly, enjoying the moneyed eavesdropping, nourishing myself as reward for the nights of overtime past, and preparation for the nights of overtime to come.

Life conditions have to be in the right balance for eating out alone to be enjoyable. I wasn’t feeling too lonely, and the meals were part of a bigger experience. There is an inherent luxury to eating alone — you only have the responsibility of feeding yourself — but it remains undeniably sad when one table over, people are laughing over a feast that you could never eat by yourself. The less that solitude is a choice, and the lonelier one is feeling, the better the food has to be.

The ultimate experience I’ve had eating alone was when I took a solo trip to Singapore, purely for 72 hours of food. In this instance, even if I’d been mortally depressed, the food would have saved me. I had lived in Singapore, I knew exactly where to go. I had no goals or hopes other than ones of gluttony. I hit hawker stall aft er hawker stall, finding no trouble as a solo diner. I was full of childhood memories and barbecued meat. If I wanted to get another dish, I used the pack-of-tissues-on-the-table trick, which is de facto Singaporean law, to save my seat. It was the most focused I’d ever been in my life. There was nothing but me and chicken rice, chai tow kway, char kway teow, prawn noodles, satay, bak chor mee, ice kachang. When I wasn’t eating, I was digesting and stocking up on food to take back — lapis cake and pineapple tarts.

To some, the sight of someone eating alone is the saddest thing you could see. If only such people could have seen me in Singapore — disgusting, yes; sad, definitely not. And after all, the saddest sight is someone eating at their office desk. This I have also done frequently, because not every day held a vegetarian monk degustation or a Hungry Hungry Hippos-style tour of Singapore. As much as I try to keep meals untainted by the grime of capitalist labour, there were times when al desko lunches and dinners were the only option.

Here, proximity and speed were the ruling factors, easy fulfilments in Hong Kong. I’d get fried hor fun and beansprouts, egg and tomato rice, or vegetable and egg white fried rice, all available downstairs and ready in less than 15 minutes. In front of my screens, blurrily clicking at something, I’d shovel the food from the polystyrene container into my mouth, barely even looking down. It was always piping hot and full of sodium; it was textbook sustenance.

Even off-desk, eating alone was routine in Hong Kong. The work hours were long and the income tax was low. I rotated through residences: grandparents’ storage room, co-living, hotel, serviced apartment. The only time I had my own kitchen was in the serviced apartment. It was a metre wide and within an arm’s reach from the bed. As much as I loved eggs à la supine, it was only natural that I ate out a lot, often alone. It was too easy. Affordable deliciousness was on every corner. Noodle shops with plastic stools, standing snack bars, dim sum to-go — these places became routine, a passing craving, cheap and cheerful 10-minute meals. I’d scoff down food and not realise how hungry I was until I was ordering a second serving.

Sometimes routine would turn into ritual — I’d step into a cha chaan teng diner for a quick bite, and find myself in a Formica-and-floral-tiled booth that was literally where a Wong Kar-Wai movie had been filmed and I’d find myself romantically spacing out, pretending poorly that I was Faye Wong. The magic of a cha chaan teng is that it is fast food in an absolutely boutique manner. The most classic of these diners have their original 60s fitted booths, and every surface is tinted with age. You can imagine the ghosts of diners past; the furniture tells you that thousands of milk teas have been drunk here; and this history elevates your own meal. You know that you’re the latest in a long string of people who have sipped from the thick ceramic cup. The restaurant itself is a patina in motion, an ambience impossible to recreate.

But more often, the differentiator between routine or ritual was money — in Hong Kong, you can find an absolutely delicious meal for $500 or you can find an absolutely delicious meal for $5. The differences are mostly material: what type of chair you sit on, if you have a chair to sit on, the lighting, the noise, the presence of air-con, the altitude of the restaurant. On work nights that were too late to attempt cooking but not too late for shops to have closed, I would frequent a branch of a mid-tier sushi chain in an upper-tier shopping mall where dinner would cost about $30. A mid-tier ritual. I liked this place not because it had the best sushi but because it had very cosy bar seating. The perfect bar seat is every solo diner’s white whale and this was a good find. Despite being a chain, this sushi place felt bespoke. With warm wood and dark marble in dim lighting, it felt like somewhere a businessman in the 80s would eat. It also had the rare quality of having just the right amount and make of background diners to make you feel like you had company when you didn’t. It was perfect for nights when I didn’t have any plans and didn’t feel like going home. They also had one dish which I haven’t found anywhere else — a very simple starter of cucumber and moromi miso: the perfect fresh, crunchy, salty snack at the end of a long day.

These days I am in London, working a much less demanding and also much less rewarding job. The office culture deems lunch a solo affair. There is a nearby street market, and my favourite stall offers three curries and rice for $10, a bargain for Zone 1. On fine days I take it to a square outside an 18th-century church and eat it on a bench, where other people from other offices do the same. Pigeons peck around our feet. People say that British food is terrible, but I feel I don’t really know what ‘British’ food is. The food I eat is Indian, Turkish, Chinese, Greek, Nigerian — it’s all British and not British at the same time. And delicious. During my lone lunches, the food is good enough that I don’t think about how this is not getting closer to who I want to be. The job has much better hours than my previous ones, but it’s also completely dissatisfying. I take another bite of spiced potato. The suppression works.

The most recent and one of the saddest meals I had alone was a bowl of broccoli soup and a huge chunk of bread at the Barbican, a sprawling brutalist labyrinth of apartments and public space. It was aft er work, but I had gone there as it was a good place to keep working. Having finished my day job, I could catch up on some writing. I looked at my Word document, which was full of words entirely for myself. Once again, I was eating in front of a screen, alone. I buttered the bread and positioned it above the green swamp in the bowl. I had no expectations; it was the cheapest thing they had. The canteen-style restaurant had everything that, on paper, was perfect for solo dining: plentiful window-facing bar seats, self-service, a chatty ambience. But despite the generous height of the bread and the gentle savouriness of the soup, it wasn’t enough. I needed sustenance but received only mediocrity. Was this British food? I was not in Singapore, the land of food ecstasy; I was in London, the city of Pret a Mangers, a chain seemingly designed to remind society that the only acceptable form of eating alone is a quick cold sandwich, consumed while walking. It’s also the most expensive place to eat out I’ve ever lived in, and this reduces the culture of impromptu solo meals that is so normal throughout Asia. Nor does it have the more European culture of everyman cafe lounging. Here the cafes and pubs are for workmates or friends, adding to the social intimidation of the lone diner. I wish I had a Wendy’s hot dog instead.

It’s hard to make friends as an adult, but it’s easy to order food. The lack of company shouldn’t mean a lack of satisfaction. Choux à la crème in Paris, tortellini in Bologna, mandu in Seoul: all completely delicious without conversation. Eating alone all these years has made me wonder if I’m introverted by nature or by need. I also wonder if I’ll still enjoy eating alone when I am 60, 70, older — and if at that age I’ll be living somewhere where I’ll want to eat out alone. All I know is that if I didn’t eat out alone, I would have missed out on some of the best meals of my life.

Sharon Lam is the author of the novel Lonely Asian Woman (2019).

–