May 9, 2019 Restaurants

The Supreme Winner of the Metro Peugeot Restaurant of the Year Awards 2019 combines meticulous technique, deceptive simplicity and soaring ambition. After enduring money troubles, a breakdown and a break-up, Pasture’s Ed Verner is finally finding firmer ground – and puts no limits on what he can achieve.

This story first appeared in the May -June 2019 issue of Metro magazine.

For more great videos, check out our Youtube Channel.

When you arrive at Pasture, the door is locked. You pull at the handle again, just to be sure, but it’s definitely locked. Then you notice the sign: “Doors Open 5.45pm & 8.15pm”. And they do. At precisely 5.45 or 8.15pm, you hear a click and the door is opened by Ed Verner — chef, owner, front of house, manager, sommelier, bartender, dishwasher, and cleaner of Pasture, Metro’s Restaurant of the Year 2019.

Verner welcomes you into a small lobby, pours you a juice of green tomato and melon, with green chilli ice that makes the drink spicier with every sip. Something’s happening here, it tells you. Get ready.

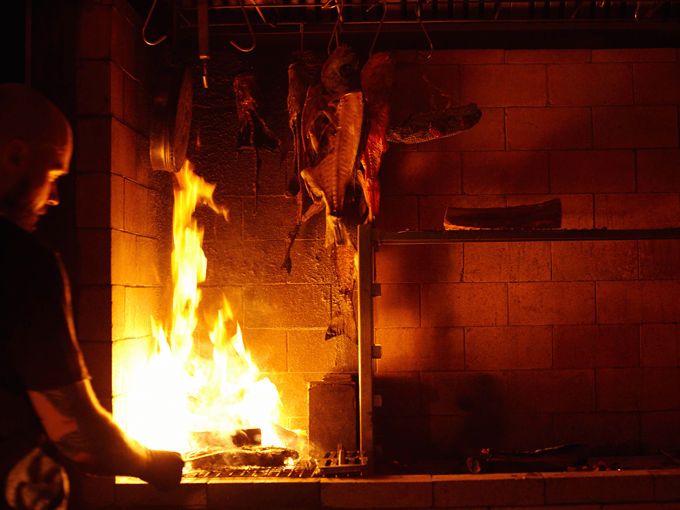

For the next three hours or so, you are in the hands of Verner and his two fellow chefs, Tatsuya Shinkai and Agata Alicja. They do everything, right in front of you. The three chefs cook your food (much of it over an open flame), mix your cocktails, pour your wines, clear your plates, sweep your crumbs from the bartop, all with a fine balance of friendly casualness and stoic perfectionism. The chefs are always on view. When they talk to each other, they lean in and whisper, critiquing and finishing dishes in hushed tones. Their movements are quick and precise. Every action is efficient. Every dish is foreshadowed — the tomatoes hanging in a basket over the fire will be on your plate in half an hour or so. And they’ll be the best tomatoes you’ve ever eaten.

The food at Pasture is a miraculous combination of meticulous technique, rustic warmth, deceptive simplicity and grand ambition. Verner’s 13- to 15-course set menu is matched with either a combination of obscure, low-intervention wines, carefully chosen craft beer and inventive cocktails or a non-alcoholic pairing that takes non-alcoholic drinks as seriously as the cocktails. It is as refined as any white-tablecloth restaurant, yet as personal as an intimate dinner party at a friend’s house, if your friend was the best chef in Auckland.

It’s been an intense year for Verner. In October, he and his then-wife (and then-co-owner), Laura, transformed the restaurant from a cosy 20 seats (down from 30 when it opened, then 24 shortly after) to just six seats, all at a bar along the pass, right in front of the fire and stove.

Pasture had been open for over two years, and despite several accolades (including Metro’s Best New Restaurant award in 2017), enthusiastic reviews and trend-piece press attention branding the restaurant as the product of a young, hip couple who foraged in the Domain for wild herbs, it just never quite took off. They struggled to fill the restaurant, yet had to retain enough staff and stock in case more people showed up.

Reducing the seat count instantly transformed the restaurant. For the first three weeks, Verner cooked alone while Laura worked front of house. “Pasture has been at a crossroads many, many times,” he says in the restaurant’s lounge on a day off. “And every time we’re at a crossroads, Pasture has to do something. It’s fight or flight. Do or die. Close the restaurant or change it. So I changed it. But I didn’t want to dumb it down. I didn’t want to offer à la carte, I didn’t want to offer a shorter menu; it’s just not what would make me happy. What makes me happy is doing something exciting and interesting creatively. I’m not here to make money. That’d be nice one day, but I just want to do what I want to do and I want to make people happy. That’s what I get a kick out of.”

At the end of December, just two months after they reduced the size of the restaurant, Laura left him. And Pasture. “Laura’s not with me any more — that’s changed everything,” he says, sadly but matter-of-factly, eyes sunken and red from the unending labour of running Pasture alone. “I do everything now. I’m doing the laundry, cleaning the toilets, polishing the glasses. I’m in touch with every part of the restaurant and that feels good. It pushes me a bit too far, a bit too often, but the whole experience at Pasture is controlled by me. The menu, the wine, the cocktails. I feel a deep connection to everything we do here… I’ve made it harder for myself because I’ve created something where I can’t have a bigger team. If I had a bigger team, it wouldn’t be as full-on, but it wouldn’t be as special.”

Since the drop to six seats, Verner’s food, and his vision for the restaurant, have come into sharp focus. Every aspect of the experience is informed by the format. “There are certain theatrics to what we do,” he says. “I think about how things will play out in front of people. I get to show people how things are made. I’ll bring the cow down for people to see. It’s a real connection. You can’t do that table by table.”

That cow is locally sourced wagyu (Pasture is the only local restaurant buyer; the rest gets shipped to Japan), aged for two to three months out the back and cooked over flames in a darkened dining room while AC/DC plays loud. Like the tomato, it’s probably the best you’ve ever eaten. As is the snapper. And the crumpet. And maybe the bread and butter, too. If the food weren’t transcendently satisfying, and Verner so earnestly personable, the whole thing could come off as clawing or awkward. But the food doesn’t just stand up to the performance, it exceeds it.

Verner and his chefs present each dish and drink, talking you through the menu that you can’t read until you leave. You see the work behind everything. Or you think you do. Seeing each component come together makes it look simple, but what you don’t see is everything that happened before you got there. The intensive prep, the sourdough that takes three days to make, the butter that was churned a year before you eat it, the fermentations and concoctions that look like the stockroom of a 17th-century doctor. You can see the sparks and flames, the skill and technique, but you can’t see the time.

“My food is about simplicity,” Verner says like it’s the most important thing he could say about Pasture. “I hate complicated food. It’s always simple. Super-simple. So much so I often get insecure about it. But I just love simplicity. It’s clever, what goes on behind it, but I want people to just see the simple. In my time eating around the world, the dishes I remember are always the simple ones.”

And it’s not just the food. The entire experience is based on an almost monastic simplicity masking a perfectionist’s complexity. Everything — the locked door, the fire, the AC/DC, the chefs clearing your plates — combines into a dining experience that truly feels like the result of one person’s experiences, good and bad, up until that very night. Some of it is pure necessity — Verner doing whatever it takes to keep Pasture open — some of it pure theatre. “There are no rules at Pasture,” he says declaratively. “I hate rules. I was never a head chef before, so I’m not set in anything. Like, I thought, Fuck it, I’m going to lock the door. If you’re coming to a fine-dining restaurant and you’re paying this price, you should probably be welcomed and be sat down and be comfortable, but I don’t have the manpower for that. So I’m like, Fuck it, lock the door, put a sign out: we open at 5.45 and 8.15.”

Verner’s energy builds as he talks. His complete dedication to Pasture (he’s reluctant to call it an obsession) rushes through his veins, curing any exhaustion brought on by the pressure of the task he’s set himself. “I feel stronger now,” he says definitely. “It’s made me stronger. I can do anything here now.”

Ed Verner, 36, is from a small town in Dorset, England. He fell in love with food on a trip to Japan, paid for with an insurance payout for a rugby injury. In 2010, a girlfriend got a job in New Zealand so Verner packed his knives and moved with her. He worked at Merediths and Sidart , then completely reinvented the food at Stafford Rd Wine Bar (which Metro awarded four spoons in our March 2014 issue). Just as his food started getting recognition, he went back to Europe a couple of times, working unpaid at Relae in Copenhagen and In De Wulf in Belgium.

When he returned, full of ideas, he knew he needed his own restaurant. “I got to a point where working for someone else wasn’t making me happy,” he says. “I had all this stuff inside me and I was just obsessed with getting it out. I did a few pop-ups and people responded well to them, but I thought they were terrible. I enjoyed the process but I got frustrated because I wanted to do this every day. I was hungry for an outlet. And Laura is an amazing creative person and I knew that both of us had a huge amount to give.”

The initial concept for Pasture was a small restaurant, with an open kitchen built around a fire. It would have a single set menu and be “very cheap” and “accessible to everyone”. They wanted to open in Clevedon but couldn’t find somewhere affordable, so when they found the perfect room, opened down a lane in Parnell instead. The opening menu was $115. It lost money immediately.

Months after opening, Verner had a nervous breakdown and had to shut the restaurant for three days. “I was trembling, I was crying,” he says. “I was like, ‘I can’t do this’. For months, I’d wake up with nausea, like I was going to throw up every morning, just from the pressure of it all.”

Later, Pasture’s entire staff, other than Ed and Laura, quit at the same time. The atmosphere in the kitchen could deteriorate in conflict. Verner developed a reputation as someone difficult to work for. Some chefs worked a single day and never came back. “I certainly wasn’t equipped at the start,” he says. “It’s tough to be great in every area — to be a creative person, the cook, the manager, the leader. And I’d never been a head chef before. So I’m the first to admit I was never the best leader. I know people don’t say great things about me, but I don’t feel it’s because I treat people out of turn, or badly, it’s just because I’ve got my head down, going so hard, I’m not managing or looking after things I should be, thinking about things I should be, and then people’s wheels start to come off. It makes me sad.”

When asked about working for Verner, Shinkai laughs off the notion that he is a bad leader or difficult to work for. “Ed is a very, very hard worker — a very special, creative chef, always challenging,” he says. “It’s not too hard for me. In Japan, I used to work 90 hours a week; that’s fucking hard.”

Along with the financial and emotional instability, Pasture’s food gained a reputation for inconsistency. Frequently described as one of Auckland’s most ambitious chefs, Verner was full of ideas but his execution didn’t always match his ambition. Moments of sublimity could be followed by confoundedness, genius followed by folly.

Despite (or, perhaps, because of) the two major transformations of the past six months, something has clicked for Verner. World’s 50 Best Restaurants “Taste Hunter” Zoe Bowker called her dinner at Pasture in October the best meal she’d had in 2018. When making his decision for our supreme award, our guest judge, Pat Nourse (creative director of the Melbourne Food & Wine Festival and chair of the Oceania, Australia and New Zealand voting panel for the World’s 50 Best Restaurants awards), said his dinner at Pasture was the best meal he’d had so far in 2019. There’s a sense in which Pasture, as a restaurant, and Verner, as a chef (he is also the winner of our Best Chef award), are coming into their own, like a young musician making their first great album after an exciting debut, or a director making their first studio film with a bigger budget than they’re used to but still with the urgency and rebellion of someone free of commercial considerations.

“I feel a corner has been turned,” Verner says. “I feel Pasture has made it in terms of the concept, the menu, the feel. It feels like this is a fucking great restaurant now. When Pasture opened, everything came too soon. We were the new kid on the block. We were new, we were exciting. Everything went… bang! I’d never been a head chef before and I don’t think I was ready for it. I had in my mind what I wanted to do, but your taste and your palate develop. And it takes time to hit that consistency. I’m a better chef than I used to be and I want to be better. But I feel like something’s clicked at Pasture. It feels really special.”

Yet, as special as it is as a restaurant, Pasture is still struggling as a business. While it has the most expensive set menu in Auckland, the economics of serving no-compromise fine-dining food to a maximum of 48 diners a week are precarious. “I might not be here in two months,” he says. “It’s tough, but it’s doable. Just. I live month to month. Pasture almost shut in February. I’m just hoping for consistency. I need over 10 people a night to survive. If I can get that, I can break even.”

Still, Verner takes comfort in the down-and-nearly-out stories of his heroes. “If you look at most great chefs — and I’m not saying I’m going to be a great chef, but obviously I look up to these people and I read their books — they’ve been through this kind of time. They’ve lost relationships, alienated people, sunk to absolute lows, struggled with managing staff, had customers hate what they do, and they just push on through. All these stories help me when I’m feeling really low.

“I feel lucky to have something that I love, that I get to work on every day. I have a buzz of excitement about being able to do it and it makes me happy. I’ve probably lost friends and my marriage because of it, but this is something I love to do. It’s my passion, it’s my craft, and it fills me with a huge amount of satisfaction. If I died in 10 years, I’d feel like I achieved what I wanted to. I understand I can’t do this forever. What Pasture is now, it probably won’t be like this in five years’ time. I won’t be able to keep up. Right now, Pasture is in its young, exciting, hedonistic days. What comes next, I don’t know, but this can’t go on forever. I’m going to enjoy this time. I’m going to succeed or it’s just going to go down in flames.”

Photography by: Rebecca Zephyr Thomas