Jul 25, 2023 Restaurants

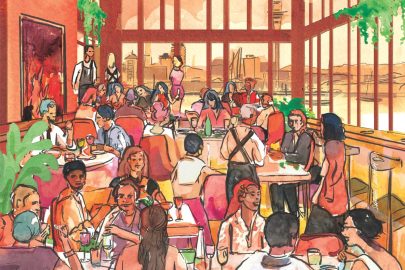

For many people, restaurants are a valued ‘third place’ — that crucial space that is not our home or workplace where we seek community and interface with the world — yet it’s easy to take them for granted. Restaurants are social hubs. They are where we celebrate, where we gossip, where we catch up with mates; where we announce pregnancies and engagements; where we sip martinis as we consider quitting our jobs and moving to London. They are a mouthpiece for our best food and beverage producers, and provide a stage for our cultural narratives. Restaurants represent who we are as a city at a moment in time. They reflect where and what we want to eat.

For several months in 2020, we faced the stark reality of a world without restaurants. Streets sat stagnant — devoid of life, diversity and delicious things we didn’t have to make ourselves. The flow-on effects of Covid were massive: supply chains broke down, producers were stuck with stock and many restaurateurs were forced to take on government loans and fall even deeper into debt. Hospitality was one of the industries completely unable to operate during lockdowns, then was further affected in 2022 as a wave of Omicron hit and customers stayed away. In many ways, it has come back stronger since then, with new openings, current owners expanding to new sites, and food offerings that continue to level up.

Most patrons who drop in to experience a night of good food and service and be taken out of their day-to-day lives don’t realise what goes on behind the scenes. For them, I wanted to look inside and ask: how, exactly, are our restaurants doing? And is it possible to make a profit running one? The restaurant industry in Tāmaki Makaurau appears to be thriving, but insiders are troubled by staffing shortages as well as the effects of rising food costs, wages and interest rates on already razor-thin margins. I was curious to know what drives people to launch restaurants, and why, despite these challenges, they continue to forge ahead across the city.

On Auckland’s Dominion Rd, a stretch known for having more than 100 restaurants from many cultures, Plabita Florence is about to reopen her vegetarian restaurant, Forest , in new premises. There are gold enoki mushrooms on the papered-up window and, peeking through, I can see a freshly painted green ceiling. Inside, salt-preserved yuzu sit in jars — they will soon find a home on the menu. It’s been a bumpy road for Florence since she signed the lease late last year, but she’s grateful to be able to do something she cares about. “It gives people the opportunity to connect with my ideas,” she says. “I get to feel like I’m contributing something.”

Florence is funding Forest 2.0 through bank loans, donations and investors. Local firm Pac Studio was involved with structural changes, while interior elements were designed by Hatch Workshop. Florence has just put an accessible bathroom into the space and had its sloping floor evened out. Restaurant landlords often get a sweet deal, Florence notes, when restaurateurs transform their spaces. “Putting such a huge amount of money into a place I don’t actually own feels quite insane when I think about it,” she tells me.

But paying rent is the simple reality for most restaurateurs. Rents across the city range dramatically, from a low end of $20,000 a year to more than $200,000. (This doesn’t include GST, or operating expenses like water or power.) Spaces like Queens Wharf, Takapuna, Britomart and Commercial Bay are on the more expensive end of the spectrum, though they offer higher foot traffic, marketing support, maintenance, reduced risk of competition and a “carefully curated community”, something Britomart landlord Jeremy Priddy is very proud of.

Priddy, who has 30 years of experience in commercial renting, believes that the biggest issue isn’t rent at all — it’s historically been the cost of fit-out and restaurateurs wanting to look better than their competitors. Unwilling to divulge numbers, he explains that rates within Britomart are negotiated for each business based on its needs. “This does cause some tension between tenants, but most importantly it’s about ensuring everyone can be successful,” says Priddy. He’s always on the lookout for newcomers to Britomart, and says businesses who trade there often want to open a second space. But he insists they must be new concepts: “I only want there to be one Amano .”

Savor Group, which runs Amano, MoVida and Bivacco — all large-format sites with long opening hours — is one of the few hospitality businesses that can afford to thrive in Britomart. “It makes more sense for me to be around density,” says Lucien Law, Savor’s chief executive. He cites the “formation of precincts” as one of the biggest changes he’s seen in his 12 years in the game. Sammy Akuthota, the owner and operator of the Satya and Satya Chai Lounge sites, has an entirely different model. “I’m not going to take on Ponsonby Rd rents or Commercial Bay prices,” Akuthota says. “It just doesn’t fit in the realm of what I do.”

Law says you want your rent to be around 6% to 10% of your costs, and that it’s worth getting this right. It’s the one piece you can’t change. From there, with this cost fixed, it is wages and stock costs that you have to worry about blowing out.

Finally, for real success, landlords and restaurateurs need to work in partnership. During the pandemic, many landlords offered rent reductions, some of up to 80%. At the start of a tenancy, too, some landlords will offer a rent holiday, allowing operators a few months to renovate, get things sorted and apply for licensing. But it always takes longer than you think.

On another popular eating street, Karangahape Rd, Brazilian chef Fabio Bernardini is about to open Tempero, a South American-inspired restaurant in the old Peach Pit site. There, he’ll be sharing his collection of cachaça (a spirit made from fermented sugarcane juice) and dishes of Brazil — such as soul-warming moqueca, a Brazilian fish stew with coconut milk and lime served with rice. With a stint at Mexico’s Pujol (a restaurant which, for a decade, was ranked among the best in the world) and experience working alongside Michael Meredith, Bernardini knows the potential hazards ahead and has already negotiated a few.

“The bureaucracy to set up a restaurant is really unfair to the operator,” he says. “It’s so uncertain, with no guarantees.” Bernardini and his partner, Tiffany Low, were ready to move in in December, but it took five months to close out the lease thanks to issues with a demolition clause and challenges with agents and landlords. Now they are hoping to be open in July, having spent the last few months rebuilding the interior and painting the bathroom a deep Amazon-rainforest green.

Problems with liquor licences and resource consents can also mean delays. Changing the designation of a site from retail to hospitality is particularly arduous and costly. Florence faced this issue with Forest — the new premises required resource consent and an elaborate fire protection system, including the installation of an alarm in the apartment next door. This, along with an expensive extraction unit and the need for council sign-off, caused a six-month delay to Florence’s original plan for opening the doors, now likely July instead of January. It’s a hard financial situation for a business yet to serve its first hibiscus negroni or seaweed fries.

At Duo, an all-day eatery in Birkenhead Pt, owners Jordan and Sarah MacDonald applied for a liquor licence three months before they opened. It took a whopping nine months to come through, deterring their initial plans to open evenings. “It was a lot of screwing around,” says Jordan, explaining there were complications with a historical resource consent and another small detail they had to change. Six months after they opened, diners could finally order a cappelletti spritz alongside their brûléed custard loaf. Jordan and Sarah now have a new venture under way, a pasta joint called Osteria Uno . They’ve already had to adjust their plans for the site to ensure they can meet the demands of council and compliance without sacrificing design or accessibility.

David Lee, the chief executive of Namu Group, which owns The Candy Shop , Aigo Noodle Bar and Pōni, admits the council side of things has always been hard to navigate. Over time, he’s gotten better at it. “When opening a new space, I always try to get a site that already has a kitchen in it. That saves a heap of money and trouble.” He’s just signed the lease for his eighth site, a character building on Ponsonby Road that he’s had his eye on for months. Though he doesn’t have a name yet or a solid plan, he wants an all-day space, where people can walk in for a beer and some fried chicken at 3pm and still get a coffee an hour later.

Lots of things can trip new business owners up, and these mistakes can have disastrous effects on your bottom line. Forgetting to renew your liquor licence on time is especially consequential, something Adriana Ferdian of Bali Nights, an Indonesian restaurant in Ponsonby, has experienced. Bali Nights was unable to sell alcohol for three months during its second year in business. Paired with a provisional tax payment, the oversight almost forced the restaurant to close.

The Auckland Council website suggests operators should allow for six weeks to process a liquor licence application, as long as all documents are present and there’s no public opposition. According to the operators I spoke to, however, it can take anywhere from three to nine months to get the final licence. It costs around $1,500, an amount that increases based on how late you plan to serve alcohol. The cost of an outdoor dining licence is another killer: between $1,500 and $2,500 a year, depending on suburb location and size of space.

While most operators accept that Auckland Council is merely doing its job to ensure sites comply, some grumble that its role feels like ticket clipping. Akuthota says he wishes the council would offer more support to those entering the game — perhaps providing business training to ensure operators have a good chance of success. As with the food control plans that all food businesses must make and have verified with the council or the Ministry for Primary Industries, seeking licences and maintaining compliance come with extra costs that add up.

—

“If you were in a really great position, you might do something smarter with your money,” says Jordan MacDonald. Certainly, the restaurant industry is not exactly renowned for being low maintenance with high returns. Among those I talked to, business experience and financial circumstances varied dramatically. Capital to get into business seemed to come from either personal savings in a previous career, taking over the family business, bank loans, family loans, extended mortgages or, in some cases, investors.

Akuthota has worked in his family’s South Indian restaurants since he was 11, and took over from his parents in 2008. No money was exchanged — he’d already paid his way through hours on the floor. Essentially born and bred into the industry, Akuthota believes it takes a special type to thrive. “Hospo people are just different. The love for it is what drives us.”

Jordan and Sarah of Duo turned to family loans to get their foot in the door. “To set up Culprit [a central-city restaurant Jordan co-owns with Kyle Street], we borrowed a big loan from my parents. We’re still paying that off,” he tells me. I was intrigued about whether their share in Culprit allowed the Duo couple a passive income, but they laughingly said, “Maybe when we sell.”

Self-funding is another avenue, with operators channelling funds saved from previous careers into their restaurant dreams. This is the path Bernardini has taken to launch Tempero. “Basically, I’m buying myself a job,” says Bernardini. It all means hours of hard labour and starting slowly — he and his partner are renting fridges, and he’s building the bar himself. They’re watching their savings dwindle before their eyes, but they believe in their vision.

Adriana Ferdian, with no background in hospitality, resigned from her corporate marketing role in 2020. She and her husband, Bobby, opened Bali Nights in April 2021 and It’s Java on Karangahape Rd soon after. The kitchens at both restaurants serve textured plates of nasi campur Bali, flavourful with lemongrass and galangal and backed up with plenty of sambal heat. Despite Indonesia being the fourth-most-populous nation in the world, there’s a dearth of Indonesian restaurants globally. “I get so much joy and pride,” Ferdian says, “seeing authentic Indonesian food celebrated in a country that isn’t mine.” The restaurateur appears passionate and high energy, but admits it can be tough: hospitality is the ultimate contradiction between hard and fulfilling, she says.

David Lee, meanwhile, tells me that, much to his wife’s despair, he’s not a good saver. He prefers to re-invest what he makes into his businesses. He’s chosen not to seek outside investors for any of his eateries, instead collaborating with previous employees, and entering business partnerships only where he holds the decision-making power. The value of this hard-but-fulfilling independence was another clear throughline in what I heard from restaurateurs. They like the freedom of being their own bosses. Even when they are tired and hungry, mopping floors and emptying fryers late on a Saturday night, then heading home to plan menus and eat boiled potatoes with Kewpie mayonnaise (the food chefs actually eat), at least they know they’re doing it for themselves.

—

So do restaurants actually make money? Can they? There was a strong consensus among those I spoke to that they can, but that it’s getting harder and harder. The margins are tight; the profits slim. As Jordan MacDonald points out, “People think profits are a dirty word, but the reality is you need to make money to stay open.” I did, perhaps unsurprisingly, run into a lack of willingness to talk about finances in detail. This sensitive subject was famously highlighted by chef Irene Li of Mei Mei restaurant in Boston in 2020, when she opened her restaurant books to the world, breaking down each expense line by line to foster understanding about how hard the business can be. (Metro attempted to do something like that here in Auckland but no restaurants we talked to were interested.) The reticence may also reflect a general cultural shyness about money in New Zealand, but is certainly exacerbated by hospitality being a romanticised industry in which passion is valued above all else.

In order to make money, you need a vision, the right space and a formula that doesn’t feel like a formula. It’s a delicate equation that involves minimising the cost of goods, setting prices high enough to cover overheads and ensuring consistent visitation. “There are a lot of restaurants I see that haven’t put their prices up in the last three–four months, and I don’t know how that works,” says Law of Savor Group. “Obviously, we don’t want it to be unattainable but the reality is you’re not buying cheese at the same price any more.”

Many independent operators noted that the big groups were where the money was. Now a publicly listed company, Savor Group had a revenue of $52 million in 2023 (up 71% on 2022) across its 20 venues. Its newbie Bivacco alone turns over an average of $240,000 a week. “We are essentially renting out seats,” explains Law. He believes that it would help profits go up if New Zealanders embraced a later dining time. “Everyone here wants to eat at 7pm or 7.30pm. I’d like a second sitting at 9.30pm like they do overseas.” Developers or agents now approach Law about new sites, reflecting the power that exists in the bigger groups.

Traditional lore states that if a restaurant makes it through the first year, it’ll do okay, but it’s not quite that simple. Research in the United States suggests restaurants have a 60% failure rate within the first year and typically break even around year two or three. Ben Shewry of Attica in Melbourne says it’s about finding a sustainable rhythm — at Attica, he admits, they spend too much money on food. “It’s getting the right balance of food and wages that is crucial for survival.” Shewry is also an advocate for paying employees fairly, but this comes at a cost — in December 2022, his wage costs were 49% of the overall revenue. A figure like this is at the high end of more-usual 30% to 40% range.

Shewry says restaurants running a tight ship should be able to make a profit of around 3% to 5%—but with a margin figure this small, you’re never far from ending up in the negative. Profit margins do vary hugely across the board. David Lee says that if he’s making 15% profit, he’s happy, but admits this is very hard to do. However, given he has yet another outlet in the works, it’s clearly a challenge he thrives on.

Beyond the balance sheet, it can be hard to quantify why a restaurant is right, what makes it work. Is it the decor, the artful lighting, the background music or the confident service team who make you feel cared for yet allow you space? Often, it’s all of these, in sync. A restaurant doesn’t need to be flashy or fancy, just confident in itself — you can feel the difference when the people behind it care about what they’re doing.

—

Of all the moving pieces that make a restaurant truly sing, good staff is one of the most significant. Finding — and keeping — the right staff is a challenge that operators face daily, and restaurateurs have lately felt the pinch of staff shortages. We have seen signs in windows calling for staff, Instagram pleas and on-the-day closures due to illness.

Savor Group currently has 600 staff across its 20 sites, and Law says getting the right talent and ensuring they stay is difficult — though it’s getting easier now the borders have reopened, he adds. Akuthota of Satya is keen to see changes to immigration rules that would allow him to hire more people. When Duo first opened, Sarah and Jordan MacDonald struggled to find motivated staff. They now have a team of 20 and they work on looking after them. “We’re lucky that our lower rent allows us to prioritise wages,” says Sarah. “I’d love for hospitality to be a more appealing and respected career, in particular with front of house. It’s still so transient and fills a gap as they go on to other careers.”

Certainly, the work should be valued more highly than it often is. Restaurant workers don’t just feed people — every single night they’re essentially putting on a multi-faceted, well-rehearsed show. “You go to a restaurant because you want to be entertained, meet with friends and have something on your plate that you can’t make at home,” Law says.

Shewry once said that restaurants are the last boutique factories. There, groups of craftspeople make things by hand from materials that degrade daily and cost a lot of money. When we use the word ‘expensive’ to talk about a restaurant experience that we’ve enjoyed, it can do a real disservice to the industry and the individuals working in it. As Bernardini from Tempero puts it: “Food makes the world go round.” Eating at restaurants, we not only support the people directly involved, but the wider system that surrounds them: farmers, fishers, small food producers, cleaners, linen companies, delivery drivers, compost collectors and many more.

All of the operators I spoke to wanted to see more restaurants. We all love a new kid on the block — you can see it in the number of new openings and the hype around them — but I was surprised to hear my interviewees wanted more competition. There’s a camaraderie and fierce sense of bravery in these people. Though paid less than most, they hold the skill sets of many different professions: chef, front of house, chief executive, accountant, procurement specialist, social media expert, cleaner, customer service manager, handyman and everything in between. I’m genuinely in awe of their tenacity and grit. “We are like cockroaches,” Bernardini tells me. “Somehow we will survive!”

The new Forest is just a few weeks away from opening now, and Florence is tying up neverending loose ends — painting over nicks that tradespeople have left, firming up staff and wondering if the coffee cups will arrive in time. She often thinks about an adage from the well-known New York restaurateur and writer Gabrielle Hamilton. “Gabrielle talks about how owning a restaurant is like an adult relationship,” she tells me. “You have to wake up every day and keep on choosing it.”

This story was published in Metro N°439.

Available here.